Ex-Post Evaluation of LEADER+ Contract N° 30-CE-0321257/00-26

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mapping of Cultural Heritage Actions in European Union Policies, Programmes and Activities

Mapping of Cultural Heritage actions in European Union policies, programmes and activities Last update: April 2017 This mapping exercise aims to contribute to the development of a strategic approach to the preservation and valorisation of European heritage. It responds to the "Conclusions on cultural heritage as a strategic resource for a sustainable Europe" adopted by the Council of the European Union on 20th May 2014, and complements the European Commission Communication "Towards an integrated approach to cultural heritage for Europe", published on 22 July 2014. The document provides a wide (but not exhaustive) range of useful information about recent policy initiatives and support actions undertaken by the European Union in the field of cultural heritage. Table of Contents 1. CULTURE ...................................................................................................... 5 1.1 EU policy / legislation ................................................................................ 5 Council Work Plan for Culture 2015-2018 ........................................................... 5 Priority Area A: Accessible and inclusive culture .................................... 5 Priority Area B: Cultural heritage ......................................................... 5 Priority Area C: Cultural and creative sectors: Creative economy and innovation ........................................................................................ 6 Priority area D: Promotion of cultural diversity, culture in the EU external relations and -

Minutes Meeting of the 10Th Structured Dialogue with European Structural and Investments Funds' Partners Group of Experts

Ref. Ares(2019)1659727 - 13/03/2019 EUROPEAN COMMISSION DIRECTORATE-GENERAL REGIONAL AND URBAN POLICY Political and Inter-Institutional Coordination and Document Management Minutes Meeting of the 10th Structured Dialogue with European Structural and Investments Funds' partners group of experts 28 February 2019, Brussels I. APPROVAL OF THE AGENDA The Commission (DG REGIO) announced the agenda, which was approved. II. NATURE OF THE MEETING The meeting was public, i.e. recorded (available to anyone inside and outside the European Commission) but not web-streamed. It was an ordinary session dedicated to providing an update on the negotiations of the legislative package 2021-2027; the links with the European Semester, programming for the period 2021-2027; state of progress of implementation and the Open Data platform and presentation of the new policy objective 5 Europe close to citizens as proposed by the Commission. III. LIST OF POINTS DISCUSSED 1. Update on the negotiations of the post-2020 legislative package The Commission (DG EMPL) presented the state of play of discussions on the ESF+ regulation including the amendments proposed in the European Parliament report (increase of the ESF+ budget to €120.5 billion; specific objectives extended to certain target groups and actions; additional thematic concentration requirements, compulsory earmarking for YEI amongst other). On the Council side, DG EMPL mentioned the amendments proposed in the provisional agreement as regards the specific objectives of the fund such as the addition of “disadvantaged groups on the labour market” to specific objective 1 on access to employment, the split specific objective III into two. No questions nor comments from partners followed this presentation. -

A Critical Analysis of the Leader Evaluation

Academic year 2015/2016 FROM GOOD-WILL TO GOOD-USE: A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF THE LEADER EVALUATION Matteo Metta Supervisor: Dr. Barbara van Mierlo Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the joint academic degree of International Master of Science in Rural Development from Ghent University (Belgium), Agrocampus Ouest (France), Humboldt University of Berlin (Germany), Slovak University of Agriculture in Nitra (Slovakia) and University of Pisa (Italy) in collaboration with Wageningen University (The Netherlands), This thesis was elaborated and defended at Wageningen University within the framework of the European Erasmus Mundus Programme “Erasmus Mundus International Master of Science in Rural Development " (Course N° 2010-0114 – R 04- 018/001 Certification This is an unpublished M.Sc. thesis and is not prepared for further distribution. The author and the promoter give the permission to use this thesis for consultation and to copy parts of it for personal use. Every other use is subject to the copyright laws, more specifically the source must be extensively specified when using results from this thesis. Dr. Barbara van Mierlo Matteo Metta _____________________ ____________________ Thesis online access release I hereby authorize the IMRD secretariat to make this thesis available on line on the IMRD website Matteo Metta _____________________ From Good-Will to Good-Use: a Critical Analysis of the LEADER evaluation 2 Abstract For the first time in the 25 years of the history of LEADER, Local Action Groups implementing this programme have been called upon to undertake the evaluation exercise at the level of their Community-Led Local Development strategies - Article 33, point 1(f) of Regulation (EU) No 1303/2013. -

LEADER Operating Rules Rural Development Programme Ireland

LEADER Operating Rules Rural Development Programme Ireland 2014 – 2020 Consolidated Updated Version 3.0 25 April 2019 Table of Contents Table of Contents ......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Acronyms and Terms .................................................................................................................................................. 7 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................... 9 2 Policy Context .............................................................................................................................................. 10 2.1 Policy Framework ................................................................................................................................. 10 2.2 LEADER Approach ................................................................................................................................. 11 2.3 The Local Development Strategy ......................................................................................................... 12 2.4 Regulatory Framework ......................................................................................................................... 12 3 LEADER Themes and Areas Eligible for funding...................................................................................... 15 3.1 Applicable Geographical -

Leader+ Profile More Competitive

K3AF07003ENC Name: Leader (Links between actions for the development of the rural economy) European Commission Programme type: Community initiative Target areas: Leader+ is structured around three actions: ® Action 1 — Support for integrated territorial development strategies of a pilot nature based on a bottom-up approach. ® Action 2 — Support for cooperation between rural territories. ® Action 3 — Networking. Priority strategic themes: The priority themes, for Leader+, laid down by the Commission are: ® making the best use of natural and cultural resources, including enhancing the value of sites; ® improving the quality of life in rural areas; ® adding value to local products, in particular by facilitating access to markets for small production units via collective actions and; ® the use of new know-how and new technologies to make products and services in rural areas Leader+ Profile more competitive. Recipients and eligible projects: Financial assistance under Leader+ is granted to partnerships, local action groups (LAGs), drawn from the public, private and non-pro t sectors to implement local development programmes in their territories. Leader+ is designed to help rural actors consider the long-term potential of their local region. It encourages the imple- mentation of integrated, high-quality and original strategies for sustainable development as well as national and transnational cooperation. In order to concentrate Community resources on the most promising local strategies and to give them maximum leverage, funding is granted according to a selective approach to a limited number of rural territories only. The selection procedure is open and rigorous. Under each local development programme, individual projects which t within the local strategy can be funded. -

Fishing Tourism As an Opportunity for Sustainable Rural Development—The Case of Galicia, Spain

land Article Fishing Tourism as an Opportunity for Sustainable Rural Development—The Case of Galicia, Spain Rubén C. Lois González and María de los Ángeles Piñeiro Antelo * Department of Geography, Faculty of Geograpy and History, University of Santiago de Compostela, 15782 Santiago de Compostela, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 7 October 2020; Accepted: 6 November 2020; Published: 8 November 2020 Abstract: The functional diversification of coastal fishing communities has been a central objective of the Common Fisheries Policy (CFP) since the early stages of its implementation. A large part of the initiatives financed throughout Europe have been linked to the creation of synergies between the fishing sector and tourism. This paper analyses the opportunities for the development of fishing tourism at the regional level, considering the investments of European and regional funds on the development of fishing tourism in Galicia. Special attention is given to the incorporation of the territorial perspective and Community-Led Local Development (CLLD) for the sustainable development of fishing areas. The results show limitations of this form of tourism in terms of employment and income, especially those developed by fishermen, despite the significant support of the regional government for this activity. This situation allows a critical reflection on the opportunity to convert fishermen into tourist guides, based on the need to diversify the economy and income of fishing communities. Keywords: fishing tourism; European fishing funds; Galicia (Spain); sustainable rural development 1. Introduction Local development is a generalised paradigm in order to initiate processes of socioeconomic progress in peripheral areas, in an attempt to respond to productive restructuring and economic crises, as stated by [1–5]. -

Lessons Learned and Effectiveness of EU Funds for Rural Development"

Briefing Requested by the CONT Committee Briefing for AGRI-CONT Joint Hearing on "LEADER experiences - lessons learned and effectiveness of EU funds for rural development" 1. Rural Development and LEADER in the Budget The current MFF for 2014-2020 invests about EUR 1 trillion. It is composed of five different categories of expenditure. LEADER and Rural Development fall under ‘Sustainable Growth: Natural Resources’ which receives EUR 420 billion and makes up 39% of the overall budget1. The biggest share (EUR 408 billion) goes into the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). The CAP consists of two pillars. The first pillar concerns direct payments and market-support measures to improve farmers’ income while the second one is dedicated to rural development. The first pillar receives 312 billion (76%) of the overall CAP. Consequently, the rural development pillar receives around EUR 100 billion (23%). The Member States have to allocate minimum 5% of their Rural Development Programmes (RDPs) to LEADER, within this MFF it will be 6,9%2. In relation to the overall CAP budget, LEADER makes up a bit more than 1%. 1 European Commission, Overview MFF 2014-2020, retrieved from: http://ec.europa.eu/budget/mff/index2014- 2020_en.cfm (last accessed 5.11.2018, 13:57) 2 European Commission, Rural Development Programmes 2014-2020, retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/sites/agriculture/files/rural-development-2014-2020/country-files/common/rdp- list_en.pdf (last accessed 5.11.2018, 14:22) Policy Department D - Budgetary Affairs EN Author: Verena Bitter Directorate-General for Internal Policies PE 621.794 IPOL| Policy Department on Budgetary Affairs 2. -

1 / 43 Follow-Up Provided by the European Commission to the Opinions of the European Committee of the Regions Plenary Session Of

Ref. Ares(2020)3005555 - 10/06/2020 FOLLOW-UP PROVIDED BY THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION TO THE OPINIONS OF THE EUROPEAN COMMITTEE OF THE REGIONS PLENARY SESSION OF FEBRUARY 2020 90th REPORT DISCLAIMER: Due to current circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic, announcements made in this report may be subject to revision in coming weeks or months. 1 / 43 N° TITLE / LEAD DG REFERENCES DG JUST 1. Strengthening the rule of law within the Union. A blueprint COM(2019) 343 final for action COR-2019-03730-00- Rapporteur: Franco IACOP (IT/PES) 01-AC CIVEX-VI/044 DG NEAR 2. Enlargement package 2019 COM(2019) 260 final Rapporteur: Jaroslav HLINKA (SK/PES) COR-2019-02727-00- 01-AC CIVEX-VI/042 DG DEVCO 3. Regions' and Cities' contribution to the development of Africa Own-initiative opinion Rapporteur: Robert ZEMAN (CZ/EPP) COR-2019-03729-00- 01-AC CIVEX-VI/043 DG EMPL 4. Brain Drain in the EU: addressing the challenge at all levels Own-initiative opinion Rapporteur: Emil BOC (RO/EPP) COR-2019-04645-00- 02-AC SEDEC-VI/052 DG ENV 5. Towards sustainable neighbourhoods and small communities – Own-initiative opinion Environment policy below municipal level COR-2019-03195-00- Rapporteur: Gaetano ARMAO (IT/EPP) 01-AC ENVE-VI/043 DG EAC 6. Culture in a Union that strives for more: the role of regions Own-initiative opinion and cities COR-2019-04646-00- Rapporteur: Vincenzo BIANCO (IT/PES) 01-AC SEDEC-VI/054 2 / 43 N°1 Strengthening the rule of law within the Union – A blueprint for action COM(2019) 343 final COR-2019-03730 – CIVEX-VI/044 138th plenary session – February 2020 Rapporteur: Franco IACOP (IT/PES) DG JUST – Commissioner REYNDERS Points of the European Committee of the Commission position Regions opinion considered essential The Committee ‘welcomes the Commission's The Commission is grateful for the support of the proposal, which recognises and attaches great Committee. -

Enabling Factors for Better Multiplier Effects of the LEADER Programme: Lessons from Romania

sustainability Article Enabling Factors for Better Multiplier Effects of the LEADER Programme: Lessons from Romania Alexandru Olar * and Mugurel I. Jitea * Department of Economic Sciences, University of Agricultural Sciences and Veterinary Medicine Cluj-Napoca, 400372 Cluj-Napoca, Romania * Correspondence: [email protected] (A.O.); [email protected] (M.I.J.) Abstract: LEADER is an EU development method that aims to stimulate local actors to cooperate and co-produce ideas and projects that otherwise would not be possible. Therefore, the Local Action Groups (LAGs) should not only focus on implementing the Local Development Strategies but also to actively contribute to the development of their territory. The aim of the present paper is to underline the most important tangible indirect multiplier effects produced by the LAGs in Romania in the 2014–2020 Programming Period and to identify the enabling characteristics and conditions for maximizing such effects in future LEADER actions. The study was conducted using the structured interview as a primary method for collecting data. The results were analyzed using the Principal Component Analysis and Hierarchical Cluster Analysis. The most important multiplier effects were the amount of non-LEADER grants that LAGs managed to attract and the innovation level of the projects supported from LEADER funding. The results show that the performance of LAGs is linked to the size of their team, their experience, and the involvement of their partners. However, not all LAGs managed to generate significant multiplier effects, suggesting that they still lack the experience Citation: Olar, A.; Jitea, M.I. necessary to successfully implement the method in their territories. -

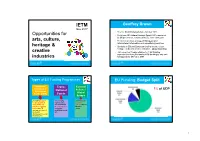

Opportunities for Arts, Culture, Heritage & Creative Industries IETM

IETM Geoffrey Brown Nov 2017 • Director, Euclid International – founded 1993 Opportunities for • Euclid was UK Cultural Contact Point (CCP), appointed by UK government, contracted by EC, from 1999-2009 arts, culture, • Euclid now provides a range of European and international information and consultancy services heritage & • Specialist in EU and European funding for arts, culture, heritage, media and creative industries - @euartsfunding creative • Just completed 7 major studies for 7 UK funding agencies identifying the levels of EU funding to arts and industries heritage in the UK since 2007 Types of EU Funding Programmes EU Funding: Budget Split European Trans- External Structural & 1% of GDP National Actions / Investment Global Funds (ESIF) Funds Europe providing support encouraging assistance for for geographical organisations countries areas within EU and individuals outside the EU which are lagging to work together, Member behind the EU undertake States average in terms of mobility projects, economic etc. development, social inclusion, etc. 1 EU Funding for Arts & Culture Types of EU Funding Programmes European Trans- External Structural & National Actions / Investment Global Funds (ESIF) Funds European Structural Europe & Investment Funds FUNDS: •Cohesion MECHANISMS TO SPEND FUNDS: •ERDF •Categories of Economic Status: (ESIF) •Less Developed Regions •ESF •Transition Regions •EAFRD •More Developed Regions •EMFF •INTERREG (involving partnerships) ESIF: ESIF: The Funds Mechanisms for Allocation • the ESIF aim to reduce regional disparities in terms of “categories” offered via… income, wealth and opportunities. FUNDS: Less developed regions Varies from country • Cohesion Fund to country: Ministry (national or regional); • European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) “growth” Transition regions delegated agencies, • European Social Fund (ESF) “people” etc. -

A LEADER Dissemination Guide Book Based on Programme Experience in Finland, Ireland and the Czech Republic

A LEADER DISSEMINATION GUIDE BOOK based on programme experience in Finland, Ireland and the Czech Republic Philip Wade Petri Rinne Final Report of the Transnational LEADER Dissemination Project for the Finnish Rural Policy Committee This report of the Transnational LEADER Dissemination Project has been unanimously ap- proved by the Streering Committee in Helsinki on April 23rd 2008. Eero Uusitalo Chairman, Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry Philip Wade Vice Chairman, former OECD Administrator Petri Rinne Secretary, LAG Manager Jouni Ponnikas Lönnrot Institute, University of Oulu Riikka Rajalahti Ministry of Foreign Affairs Marja-Liisa Tapio-Biström Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry We thank Ms Maria Forslund from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs for her participation and contribution to the meeting. ISSN 1238-6464 ISBN 978-952-227-072-6 (nid.) 978-952-227-073-3 (PDF) Vammalan Kirjapaino Oy Vammala 2008 JULKAISIJA JULKAISUN NIMI Maaseutupolitiikan yhteistyöryhmä A LEADER Dissemination Guide Book based on programme experience in Finland, Ireland and the Czech Republic SARJA / N:O ILMESTYMISAJANKOHTA 5/2008 Syyskuu 2008 ISSN ISBN (nid.) KOKONAISSIVUMÄÄRÄ ISBN (pdf) 1238-6464 978-952-227-072-6 122 978-952-227-073-3 TEKIJÄT AVAINSANAT LEADER, paikallinen toimintaryhmä, maaseu- dun kehittäminen, voimaantuminen, hallinto JULKAISUN KUVAUS Maaseutualueet kautta maailman ovat tulleet tienhaaraan: jatkuvan väestönkasvun edellyttämä maataloustuotannon tehostaminen on haaste, jonka ratkaiseminen laajamittaisella plantaasita- loudella on osoittautunut kestämättömäksi maaseutukehityksen kannalta niin Euroopassa kuin muualla maailmassa. Silti pienviljelijöillä on usein vaikeuksia toimintansa ylläpitämisessä ja kehit- tämisessä. Maatalouden koneistuminen ja vaatimus tehokkuuden lisäämisestä ovat vähentäneet alkutuotannon työpaikkoja Pohjois-Amerikassa ja Euroopassa, eivätkä uudet elinkeinot kuten matkailu ole kyenneet vielä korvaamaan tätä menetystä. -

Meeting Places and Social Capital Supporting Rural Landscape Stewardship: a Pan-European Horizon Scanning

Copyright © 2021 by the author(s). Published here under license by the Resilience Alliance. Angelstam, P., M. Fedoriak, F. Cruz, J. Muñoz-Rojas, T. Yamelynets, M. Manton, C.-L. Washbourne, D. Dobrynin, Z. Izakovičova, N. Jansson, B. Jaroszewicz, R. Kanka, M. Kavtarishvili, L. Kopperoinen, M. Lazdinis, M. J. Metzger, D. Özüt, D. Pavloska Gjorgjieska, F. J. Sijtsma, N. Stryamets, A. Tolunay, T. Turkoglu, B. Van der Moolen, A. Zagidullina, and A. Zhuk. 2021. Meeting places and social capital supporting rural landscape stewardship: A Pan-European horizon scanning. Ecology and Society 26(1):11. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-12110-260111 Research Meeting places and social capital supporting rural landscape stewardship: A Pan-European horizon scanning Per Angelstam 1, Mariia Fedoriak 2, Fatima Cruz 3, José Muñoz-Rojas 4, Taras Yamelynets 5, Michael Manton 6, Carla-Leanne Washbourne 7, Denis Dobrynin 8, Zita Izakovičova 9, Nicklas Jansson 10, Bogdan Jaroszewicz 11, Robert Kanka 9, Marika Kavtarishvili 12, Leena Kopperoinen 13, Marius Lazdinis 14, Marc J. Metzger 15, Deniz Özüt 16, Dori Pavloska Gjorgjieska 17, Frans J. Sijtsma 18, Nataliya Stryamets 19,20, Ahmet Tolunay 21, Turkay Turkoglu 22, Bert van der Moolen 23, Asiya Zagidullina 24 and Alina Zhuk 25 ABSTRACT. Achieving sustainable development as an inclusive societal process in rural landscapes, and sustainability in terms of functional green infrastructures for biodiversity conservation and ecosystem services, are wicked challenges. Competing claims from various sectors call for evidence-based adaptive collaborative governance. Leveraging such approaches requires maintenance of several forms of social interactions and capitals. Focusing on Pan-European regions with different environmental histories and cultures, we estimate the state and trends of two groups of factors underpinning rural landscape stewardship, namely, (1) traditional rural landscape and novel face-to-face as well as virtual fora for social interaction, and (2) bonding, bridging, and linking forms of social capital.