The Spirit of Colin Mccahon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mccahon House Invites You to Dinner

McCahon House invites you to dinner McCahon House hosts three Artists in Residence per year. As part of each residency a bespoke dinner between our current artist and a guest chef is created. Join us for an evening of art inspired cuisine, and be part of an ongoing dialogue where ideas around art are exchanged amongst artists and peers. These events are exclusive to the Gate Project. We Roasted carrot with kaffir lime sauce invite you to join and help strengthen opportunities and orange blossom candy floss by for New Zealand’s artists and our culture. For more chef Alex Davies of Gatherings, information about the Gate Project and to join visit: Christchurch, in collaboration with mccahonhouse.org.nz/gate 2019 artist in resident, Jess Johnson. — The Gate Project ART + OBJECT Tel +64 9 354 4646 Free 0 800 80 60 01 3 Abbey Street Fax +64 9 354 4645 Newton Auckland [email protected] www.artandobject.co.nz PO Box 68345 Wellesley Street instagram: @artandobject Auckland 1141 facebook: Art+Object youtube: ArtandObject Photography: Sam Hartnett Design: Fount–via Print: Graeme Brazier Th is auction event, including art works made solely by Colin Marti Friedlander Gretchen Albrecht underneath McCahon's "As there is a McCahon, felt like a fi tting tribute in 2019, his Centenary constant fl ow of light ..." year. We hoped to put together a small off ering that would Courtesy the Gerrard and Marti Friedlander Charitable Trust refl ect the quality and variety of work that McCahon Marti Friedlander Archive, E.H. McCormick Research produced during his life-time and I think you will fi nd that Library, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, on loan from the Gerrard and Marti Friedlander Charitable Trust, 2002 within these pages. -

![COLIN Mccahon [1919-1987 Aotearoa New Zealand] ANNE Mccahon (Née HAMBLETT) [1915-1993 Aotearoa New Zealand]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4998/colin-mccahon-1919-1987-aotearoa-new-zealand-anne-mccahon-n%C3%A9e-hamblett-1915-1993-aotearoa-new-zealand-1794998.webp)

COLIN Mccahon [1919-1987 Aotearoa New Zealand] ANNE Mccahon (Née HAMBLETT) [1915-1993 Aotearoa New Zealand]

COLIN McCAHON [1919-1987 Aotearoa New Zealand] ANNE McCAHON (née HAMBLETT) [1915-1993 Aotearoa New Zealand] [Paintings for Children] 1944 Ink, pen, watercolour on paper Private Collection [Harbour Scene - Paintings for Children] 1944 Ink, pen, watercolour on paper Collection of the Forrester Gallery. Gifted by the John C. Parsloe Trust. [Ships and Planes – Paintings for Children] 1944 Ink, pen, watercolour on paper Private Collection, Wellington Colin McCahon met fellow artist Anne Hamblett in 1937 while both studying at the Dunedin School of Art. The couple married on 21 September 1942 and went on to have four children. In the mid-1940s, Anne began a sixteen-year long career as an illustrator, often illustrating children’s books, such as At the Beach by Aileen Findlay, published in 1943. During this time, the McCahons collaborated on the series known as Paintings for Children. This would be the first and only time the couple would produce work together. The subject-matter was divided among the two, Colin was responsible for the landscape, while Anne filled each scene with bustling activity, including buildings, trains, ships, cars and people. These works were exhibited at Dunedin’s Modern Books, a co-operative book shop, in November 1945. This exhibition received positive praise from an Art New Zealand reviewer, who said: “These pictures are the purest fun: red trains rushing into and out from tunnels, through round green hills, and over viaducts against clear blue skies; bright ships queuing up for passage through amazing canals or diligently unloading at detailed wharves, people and horses and aeroplanes overhead all very serious and busy… They will be lucky children indeed who get these pictures – too lucky perhaps because the pictures should be turned into picture books and then every good child might have the lot.” 1 Two years later, in 1947, a group of Colin McCahon’s new paintings were also exhibited at Modern Books. -

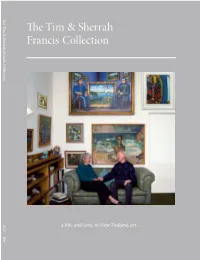

The Tim & Sherrah Francis Collection

The Tim & Sherrah FrancisTimSherrah & Collection The The Tim & Sherrah Francis Collection A+O 106 a life, and love, in New Zealand art… The Tim & Sherrah Francis Collection Art + Object 7–8 September 2016 Tim and Sherrah Francis, Washington D.C., 1990. Contents 4 Our Friends, Tim and Sherrah Jim Barr & Mary Barr 10 The Tim and Sherrah Francis Collection: A Love Story… Ben Plumbly 14 Public Programme 15 Auction Venue, Viewing and Sale details Evening One 34 Yvonne Todd: Ben Plumbly 38 Michael Illingworth: Ben Plumbly 44 Shane Cotton: Kriselle Baker 47 Tim Francis on Shane Cotton 53 Gordon Walters: Michael Dunn 64 Tim Francis on Rita Angus 67 Rita Angus: Vicki Robson 72 Colin McCahon: Michael Dunn 75 Colin McCahon: Laurence Simmons 79 Tim Francis on The Canoe Tainui 80 Colin McCahon, The Canoe Tainui: Peter Simpson 98 Bill Hammond: Peter James Smith 105 Toss Woollaston: Peter Simpson 108 Richard Killeen: Laurence Simmons 113 Milan Mrkusich: Laurence Simmons 121 Sherrah Francis on The Naïve Collection 124 Charles Tole: Gregory O’Brien 135 Tim Francis on Toss Woollaston Evening Two 140 Art 162 Sherrah Francis on The Ceramics Collection 163 New Zealand Pottery 168 International Ceramics 170 Asian Ceramics 174 Books 188 Conditions of Sale 189 Absentee Bid Form 190 Artist Index All quotes, essays and photographs are from the Francis family archive. This includes interviews and notes generously prepared by Jim Barr and Mary Barr. Our Friends, Jim Barr and Mary Barr Tim and Sherrah Tim and Sherrah in their Wellington home with Kate Newby’s Loads of Difficult. -

The Evangelist How the Light Gets in the Christian Art of Colin Mccahon

The Evangelist the exodus from Egypt (Exodus 3:14). The texts, from the Psalms, included a prayer for self-awareness: I first encountered a Colin McCahon painting in the ‘teach us to order our days rightly, that we may enter mid 1970s when I was Ecumenical Chaplain at Victoria the gate of wisdom’ (Psalm 90:12),2 and an invocation University of Wellington. A gigantic mural appeared of God’s blessing: ‘God be gracious to us and bless us, on the wall of the entrance foyer of a new lecture God make his face shine upon us that his ways may block—now known as the Maclaurin Building. It be known on earth and his saving power among all the featured an enormous 3 metre-high ‘I AM’ in white nations’ (Psalm 67:1-2). and black letters, astride a stylised but recognisably New Zealand landscape, with texts reminiscent of the I remember standing before this vast mural, awed biblical prophets. by its impact. It was a profoundly counter-cultural It was a painting to walk past, from left to right. The statement—not unlike the ‘turn or burn’ preaching left panel, showing the lowering darkness of a bush of the Jesus People movement with which it is fire or an approaching storm, seemed heavy with contemporary—warning that our secular, materialistic How the light gets in The Christian art of Colin McCahon foreboding about secular culture, ‘this dark night of society will destroy itself, unless we humble Western civilisation’. It reminded me of the words of ourselves, seek wisdom, and pursue ‘the Lord, our true Fairburn, who a generation earlier had also lamented goal’. -

Download PDF Catalogue

THE 21st CENTURY AUCTION HOUSE A+O 7 A+O THE 21st CENTURY AUCTION HOUSE 3 Abbey Street, Newton PO Box 68 345, Newton Auckland 1145, New Zealand Phone +64 9 354 4646 Freephone 0800 80 60 01 Facsimile +64 9 354 4645 [email protected] www.artandobject.co.nz Auction from 1pm Saturday 15 September 3 Abbey Street, Newton, Auckland. Note: Intending bidders are asked to turn to page 14 for viewing times and auction timing. Cover: lot 256, Dennis Knight Turner, Exhibition Thoughts on the Bev & Murray Gow Collection from John Gow and Ben Plumbly I remember vividly when I was twelve years old, hopping in the car with Dad, heading down the dusty rural Te Miro Road to Cambridge to meet the train from Auckland. There was a special package on this train, a painting that my parents had bought and I recall the ceremony of unwrapping and Mum and Dad’s obvious delight, but being completely perplexed by this ‘artwork’. Now I look at the Woollaston watercolour and think how farsighted they were. Dad’s love of art was fostered at Auckland University through meeting Diane McKegg (nee Henderson), the daughter of Louise Henderson. As a student he subsequently bought his first painting from Louise, an oil on paper, Rooftops Newmarket. After marrying Beverley South, their mutual interest in the arts ensured the collection’s growth. They visited exhibitions in the Waikato and Auckland and because Mother was a soprano soloist, and a member of the Hamilton Civic Bev and Murray Gow Choir, concert trips to Auckland, Tauranga, New Plymouth, Gisborne and other centres were in their Orakei home involved. -

A LAND of GRANITE: Mccahon and OTAGO

1 A LAND OF GRANITE: McCAHON AND OTAGO DUNEDIN PUBLIC ART GALLERY COLIN McCAHON OTAGO PENINSULA 1946-1949. OIL AND GESSO ON BOARD. COLLECTION OF DUNEDIN PUBLIC LIBRARIES KĀ KETE WĀNAKA O ŌTEPOTI, RODNEY KENNEDY BEQUEST. COURTESY OF THE COLIN McCAHON RESEARCH AND PUBLICATION TRUST 7 MARCH - 18 OCT 2020 Otago has a calmness, a coldness, almost a classic geological order. It is, perhaps, A LAND OF an Egyptian landscape, a land of calm orderly granite. ...Big hills stood in front of GRANITE: FREE ADMISSION: OPEN 10AM-5PM DAILY P. +64 3 474 3240 E. [email protected] the little hills, which rose up distantly across the plain from the flat land: there 30 The Octagon Dunedin 9016 A department of the Dunedin City Council McCAHON www.dunedin.art.museum was a landscape of splendour, and order and peace. [Colin McCahon, Beginnings Landfall 80 p.363-64 December 1966] Exhibition Partner AND OTAGO This guide was originally produced as a double-sided A1 poster for the exhibition A Land of Granite: McCahon and Otago (Dunedin Public Art Gallery, 7 March – 18 October 2020). Above is the front side of the poster and following are the texts and images from the reverse side of the poster. The reverse side has been reformated to this A4 document for either reading online or downloading and printing. The image above is: COLIN McCAHON Otago Peninsula 1946-1949 Oil on gesso on board Collection of Dunedin Public Libraries Kā Kete Wānaka o Ōtepoti, Rodney Kennedy bequest. Courtesy of the Colin McCahon Research and Publication Trust 2 A LAND OF GRANITE: McCAHON AND OTAGO A LAND OF GRANITE: DUNEDIN PUBLIC ART GALLERY McCAHON AND OTAGO A Land of Granite: Colin McCahon and Otago was developed by Dunedin Public Art Gallery. -

A Matter of Passion Marilyn Rea-Menzies

A Matter of Passion Marilyn Rea-Menzies What drives your need to seek out learning experiences? I have always had the need to be the very best that I could possibly be, and as I am self-taught I have always motivated myself to learn about other artists mainly through reading about them, visiting art galleries wherever possible to see original art works, and also through attending exhibition openings. I became quite an exhibition opening “junkie”. I am a bit of a “bookaholic” and love art books. Any spare money that I may have is often spent on books about artists working in many different mediums, and over the years, I have built up quite a collection in my library. Some of the artists who have influenced my work are New Zealand artists Colin McCahon, Louise Henderson, and John Weeks, and international artists Chuck Close, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, and David Hockney. When I came to Christchurch to live in 1994, I decided that I would try to develop my reputation as an artist as well as that of a weaver. I was known as a tapestry weaver in many circles and it is often a surprise to people when they discover that I also work in a number of other mediums such as photography, painting, drawing, and digital design. I believe that my skills as a painter and photographer, as well as my drawing abilities, inter-relate closely with my weaving; they are inseparable. To be a successful tapestry weaver I realised that I needed to keep on developing my proficiency in drawing and painting. -

An Artist's Life

Allie Eagle – an artist’s life Allie Eagle was born Alison Lesley Mitchell in Lower Hutt, Wellington, New Zealand on 9 January 1949. Her father was English-born local businessman Lesley Bernard Mitchell. Her mother was Lorna Muriel Procter who had trained as an artist under Lynley Richardson and was an accomplished portrait painter and watercolourist. Allie with her big brother Bernard and little brother Glen and their parents Lorna and Leslie Mitchell, Lower Hutt, 1956. Allie’s grandmother Muriel Jacobs was also a trained artist, having studied at the Otago School of Art from 1914 – 1918. Allie’s Great Grandfather Adnet William Jacobs was a furrier and taxidermist who worked as an assistant to the ornithologist and naturalist Sir Walter Lawry Buller, trapping and preserving a number of native birds including the now extinct huia. After Allie’s parents separated in 1962 she lived mostly with her father and two brothers in Lower Hutt, although the children commuted regularly to Rangiruru Beach near Otaki on the Kapiti Coast to visit their mother and grandparents. As a small child Allie often went with her Mother to see exhibitions at the National Gallery in Wellington. When Allie was about eight years old she recalls being taken to a show by well- known New Zealand painter Peter McIntyre who had just returned from explorations in the Antarctic. Allie remembers McIntyre in the artist’s stereotypical seaman’s jersey and beret with pipe and asking him how it was that he was able to make the sea around his icebergs look so real? When McIntyre replied that all he did was to paint waves in tones that got gradually darker, Allie knew that she wanted to be an artist herself. -

Louise Henderson Explored in New Exhibition

PRESS RELEASE FRIDAY 20 SEPTEMBER 2019 Life and Work of Artist Louise Henderson Explored in New Exhibition Louise Henderson Cubist still life 1954 Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, purchased 2019 Louise Henderson: From Life is the first major survey of work by French-born, New Zealand artist Louise Henderson (1902–1994) and opens at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki on Saturday 2 November. Featuring work from across Henderson’s seven-decade career, the exhibition traces the development of the artist’s bold and colourful abstract style. In 1925, Henderson emigrated to Christchurch to join her husband, a New Zealander, and quickly established herself as a central figure in the local art scene. She would go on to work alongside major figures including Rita Angus, John Weeks, Colin McCahon and Milan Mrkusich. Henderson was one of the first New Zealand artists to commit herself to an overtly modern style, but despite her prominence there has been no comprehensive survey of her work until now. Louise Henderson: From Life reappraises Henderson’s remarkable and complex practice, exploring the evolution of her art and the periods she spent working in Paris, Christchurch, Wellington, Auckland and the Middle East. The exhibition includes early watercolours of the Canterbury landscape, abstracted still-life compositions, sensuous Cubist representations of the female figure and lyrical explorations of the New Zealand bush. It culminates with the monumental series The Twelve Months, an ambitious undertaking that Henderson completed when she was 85 years old. In 1993, Henderson was recognised for her services to art and appointed a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire. -

Colin Mccahon, Rita Angus, Jackson Pollock and Gretchen Albrecht Are

Exemplar for internal assessment resource Art History for Achievement Standard 91489 Colin McCahon, Rita Angus, Jackson Pollock and Gretchen Albrecht are seen as very influential artists and all convey important ideas surrounding their culture and cultural experience. In an article by Anthony White published in the National Gallery of Australia website: Jackson Pollock, Before Blue Poles, White discusses his viewpoints concerning Pollock’s artwork Blue Poles, how he creates his work and how that links to the idea of culture, From the publication of the article, it is evident that the article was intended for fans of Pollock’s work, people who were just as eager as White to articulate the artwork and people who have an interest in attending the gallery. The tone of the article would also work for a wider audience of people to introduce them to Pollock’s art culture. White begins his article by expressing how “Pollock’s last monumental abstract painting, Blue Poles, is the final instalment in a series of works which have changed the course of modern art”. White then expands this to explain that Pollock’s painting is a key piece in art, changing and influencing the way the artists and audiences of our modern culture treat art; changing the way we view art and even understand what art can be. White justifies his view by referencing an interview with Pollock on the subject of “his unusual method of painting” where Pollock says that “the modern painter cannot express this age, the airplane, and the atom bomb, the radio in the forms of the Renaissance or of any other past culture”. -

Mccahon, Colin and Anne : Papers ARC-0772

FINDING AID FOR McCahon, Colin and Anne : Papers ARC-0772 User-Friendly Archival Software Tools provided by v1.2 Summary The "McCahon, Colin and Anne : Papers" Group contains: 0 Subgroups or Sous-fonds 14 Series 0 Sub-series 0 Sub-sub-series 0 Files 0 File parts 323 Items 9 Components Table of Contents ........................................................................................................................Scope and Content ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... ........................................................................................................................Provenance .................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. -

COLIN Mccahon, HIGH ART, and the COMMON CULTURE 1947-2000

1 ‘THE AWFUL STUFF’: COLIN McCAHON, HIGH ART, AND THE COMMON CULTURE 1947-2000 Lara Strongman A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington In fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Victoria University of Wellington 2013 2 Why this sudden uneasiness and confusion? (How serious the faces have become.) Why are the streets and squares emptying so quickly, As everyone turns homeward, deep in thought? Because it is night, and the barbarians have not arrived. And some people have come from the borders saying that there are no longer any barbarians. And now what will become of us, without any barbarians? After all, those people were a solution. — Constantin Cavafy, from ‘Waiting for the Barbarians’, 1904 3 CONTENTS ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................................... 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ....................................................................................................... 7 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS ................................................................................................... 11 INTRODUCTION: HIGH ART AND THE COMMON CULTURE ..................................... 14 A note on terms .................................................................................................................... 27 PART ONE: COLIN MCCAHON 1947-1950: ‘SEEKING CULTURE IN THE WRONG PLACES’ ................................................................................................................................