Idaho Panhandle National Forests FOREST PLAN MONITORING and EVALUATION REPORTS 2007, 2008 and 2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction to Short-Season Gardening in Idaho by Stephen L

SHORT-SEASON, HIGH-ALTITUDE GARDENING BULLETIN 857 Introduction to short-season gardening in Idaho by Stephen L. Love, Kathy Noble, and Stuart Parkinson INTRODUCTION Many of us who garden in Idaho face the challenges brought on by lack of summer warmth, spring and fall frost, extreme winter cold, or desiccation from frequent wind. Growing beautiful and productive plants in the high CONTENTS desert or mountain regions of Idaho requires unique approaches and an attention to detail that are rarely discussed in popular garden guides. INTRODUCTION . 1 DEFINING THE SHORT-SEASON, HIGH-ALTITUDE This publication introduces the Short-Season/High-Altitude Gardening series ZONE . 1 specifically designed to provide effective, comprehensive ideas for gardening IDAHO’S THREE SHORT-SEASON CLIMATES . 2 where Idaho’s unique combination of extreme climate, weather, geology, and NUANCES OF MICROCLIMATE . 4 Rural vs. Urban . 4 geography presents obstacles to successful gardening. Subsequent publications Slope and Aspect . 4 provide details on managing specific kinds of plants in the short-season garden. Local Weather Patterns . 4 DEFINING THE SHORT-SEASON, HIGH-ALTITUDE ZONE The Short-Season/High-Altitude Gardening series is for gardeners living within Idaho’s harshest climates, specifically those rated USDA hardiness YOU ARE A SHORT-SEASON, HIGH-ALTITUDE GARDENER IF: zone 4 or colder, situated at an elevation above 4,500 feet, or with a frost- free period of fewer than 110 days. Although many locales throughout the You live in Idaho at an elevation above 4,500 feet, OR state experience these conditions, they are most common in the upper Snake Your USDA hardiness zone is 4 or lower, OR River Valley, the southeastern and southern highlands, the high deserts north You have a frost-free growing season of 110 days or less of the Snake River, the central mountains, and the coldest valley and moun- tain locations in the northern panhandle. -

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors wish to acknowledge the Mike Stimak, Bureau of Land Management, following individuals for their contributions Coeur d'Alene, Idaho - Photo Interpretation Team to selected sections of this document: Leader (Idaho) Liz Hill, USDA Forest Service, Kalispell, Montana Pat Bourgeron, The Nature Conservancy, Boulder, - Photo Interpretation Technical Advice Colorado - Potential Vegetation Settings John Lane, USDA Forest Service, Billings, Paul Hessburg, USDA Forest Service, Wenatchee, Montana - GIS Work Washington - Drainage Basin Settings- Subsampling Gary Raines, U.S. Geological Survey, Reno, Nevada - GIS Work Hope Humphries, The Nature Conservancy, Boulder, Colorado - Vegetation Response to Jim Barber, USDA Forest Service, Dillon, Climate Change Montana - GIS Work Sue Ferguson, Forestry Sciences Laboratory, Jim Menakis, USDA Forest Service, Missoula, Seattle, Washington - Climatology Montana - GIS Work Peggy Polichio, USDA Forest Service, Coeur The following individuals and groups also d'Alene, Idaho - Logistical Support provided important assistance to the John Caratti, Heritage Program, Helena, Montana development of information contained in - Data Analysis this document: Tim McGarvey, Heritage Program, Helena, Judy Tripp, USDA Forest Service, Missoula, Montana - Data Analysis Montana - Editorial Assistance Mary Manning, USDA Forest Service, Missoula, Cathy Maynard, USDA Forest Service, Helena, Montana - Data Analysis Montana - GIS Coordination Mick Quinn, Contractor, Missoula, Montana - NRIS, State Library, Helena, -

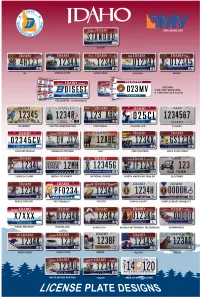

To See a Complete List of All Special Plates Types Available

2021 SPECIAL LICENSE PLATE FUND INFORMATION Plate Program Fund Name Responsible Organization (Idaho Code) Program Purpose Friends of 4-H Division University of Idaho Foundation 4H (49-420M) Funds to be used for educational events, training materials for youth and leaders, and to better prepare Idaho youth for future careers. Agriculture Ag in the Classroom Account Department of Agriculture (49-417B) Develop and present an ed. program for K-12 students with a better understanding of the crucial role of agriculture today, and how Idaho agriculture relates to the world. Appaloosa N/A Appaloosa Horse Club (49-420C) Funding of youth horse programs in Idaho. Idaho Aviation Foundation Idaho Aviation Association Aviation (49-420K) Funds use by the Idaho Aviation Foundation for grants relating to the maintenance, upgrade and development of airstrips and for improving access and promoting safety at backcountry and recreational airports in Idaho. N/A - Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation Biking (49-419E) Funds shall be used exclusively for the preservation, maintenance, and expansion of recreational trails within the state of Idaho and on which mountain biking is permitted. Capitol Commission Idaho Capitol Endowment Income Fund – IC 67-1611 Capitol Commission (49-420A) To help fund the restoration of the Idaho Capitol building located in Boise, Idaho. Centennial Highway Distribution Account Idaho Transportation Department (49-416) All revenue shall be deposited in the highway distribution account. Choose Life N/A Choose Life Idaho, Inc. (49-420R) To help support pregnancy help centers in Idaho. To engage in education and support of adoption as a positive choice for women, thus encouraging alternatives to abortion. -

Greater Sandpoint Greenprint Final Report

Greater Sandpoint Greenprint Final Report Greater Sandpoint Greenprint Final Report The Trust for Public Land March Printed on 100% recycled paper. © 2016 The Trust for Public Land. The Trust for Public Land creates parks and protects land for people, ensuring healthy, livable communities for generations to come. tpl.org Table of contents Preface ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Executive summary .................................................................................................................. 5 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................... 6 2. Study area ....................................................................................................................... 9 3. Community engagement ........................................................................................... 12 4. Mapping conservation values .................................................................................... 15 5. Greater Sandpoint Greenprint action plan .............................................................. 26 6. Profiles in conservation ............................................................................................... 28 7. Conclusion ................................................................................................................... 30 Appendix A: Participants Lists ............................................................................................. -

Biking the Idaho Panhandle on the Rails to Trails Trip Guide Biking the Idaho Pan Handle

Biking the Idaho Panhandle on the Rails to Trails Trip Guide Biking the Idaho Pan Handle Oregon River Experiences office: 503-563-1500 email: [email protected] web site: www.oregonriver.com Idaho Panhandle Rails To Trails Bicycling The Trail of the Coeur d’Alenes is one of the most spectacular trails in the western United States. This trail along with the Centennial and Hiawatha Trails make for an area full of geology and mining history. The 73-mile Trail of the Coeur d’Alenes paved trail spans the Idaho panhandle between Mullan and Plummer. It was created through a unique partnership between the Coeur d’Alene Tribe, Union Pacific Railroad, the U. S. Government, and the State of Idaho. The trail meanders through the historic Silver Valley, along the Coeur d’Alene River past scenic Lake Coeur d’Alene and through rolling farmlands to Plummer. Twenty developed trailheads provide entry points, and there are twenty scenic waysides along the route with tables to stop for a picnic or a short rest. The Hiawatha trail, is the crown jewel of our nation’s Rails to Trails routes. This special day takes you through nine train tunnels and across seven trestles with views of the towering Bitterroot Mountains. Enjoy a day cycling around and exploring the lake side town of Coeur d’Alenes on the historic North Idaho Centennial trail. This trail meanders along the waterfront and takes in the history of the town. Local History Silver was discovered in the area in 1884 and soon a rail line was constructed to support the growing mining, timber, and supply industries. -

10. Palouse Prairie Section

10. Palouse Prairie Section Section Description The Palouse Prairie Section, part of the Columbia Plateau Ecoregion, is located along the western border of northern Idaho, extending west into Washington (Fig. 10.1, Fig. 10.2). This section is characterized by dissected loess-covered basalt plains, undulating plateaus, and river breaks. Elevation ranges from 220 to 1,700 m (722 to 5,577 ft). Soils are generally deep, loamy to silty, and have formed in loess, alluvium, or glacial outwash. The lower reaches and confluence of the Snake and Clearwater rivers are major waterbodies. Climate is maritime influenced. Precipitation ranges from 25 to 76 cm (10 to 30 in) annually, falling primarily during the fall, winter, and spring, and winter precipitation falls mostly as snow. Summers are relatively dry. Average annual temperature ranges from 7 to 12 ºC (45 to 54 ºF). The growing season varies with elevation and lasts 100 to 170 days. Population centers within the Idaho portion of the section are Lewiston and Moscow, and small agricultural communities are dispersed throughout. Outdoor recreational opportunities include hunting, angling, hiking, biking, and wildlife viewing. The largest Idaho Palouse Prairie grassland remnant on Gormsen Butte, south of Department of Fish and Moscow, Idaho with cropland surrounding © 2008 Janice Hill Game (IDFG) Wildlife Management Area (WMA) in Idaho, Craig Mountain WMA, is partially located within this section. The deep and highly-productive soils of the Palouse Prairie have made dryland farming the primary land use in this section. Approximately 44% of the land is used for agriculture with most farming operations occurring on private land. -

Characterization of Ecoregions of Idaho

1 0 . C o l u m b i a P l a t e a u 1 3 . C e n t r a l B a s i n a n d R a n g e Ecoregion 10 is an arid grassland and sagebrush steppe that is surrounded by moister, predominantly forested, mountainous ecoregions. It is Ecoregion 13 is internally-drained and composed of north-trending, fault-block ranges and intervening, drier basins. It is vast and includes parts underlain by thick basalt. In the east, where precipitation is greater, deep loess soils have been extensively cultivated for wheat. of Nevada, Utah, California, and Idaho. In Idaho, sagebrush grassland, saltbush–greasewood, mountain brush, and woodland occur; forests are absent unlike in the cooler, wetter, more rugged Ecoregion 19. Grazing is widespread. Cropland is less common than in Ecoregions 12 and 80. Ecoregions of Idaho The unforested hills and plateaus of the Dissected Loess Uplands ecoregion are cut by the canyons of Ecoregion 10l and are disjunct. 10f Pure grasslands dominate lower elevations. Mountain brush grows on higher, moister sites. Grazing and farming have eliminated The arid Shadscale-Dominated Saline Basins ecoregion is nearly flat, internally-drained, and has light-colored alkaline soils that are Ecoregions denote areas of general similarity in ecosystems and in the type, quality, and America into 15 ecological regions. Level II divides the continent into 52 regions Literature Cited: much of the original plant cover. Nevertheless, Ecoregion 10f is not as suited to farming as Ecoregions 10h and 10j because it has thinner soils. -

Southern Idaho Fast Facts

Southern Idaho Fast Facts Location: Contact: Located in south-central Idaho, the mighty Snake River and its magnificent canyon etch the Lisa Buddecke boundary of Southern Idaho’s numerous cities. Boise, the state capital, is about a 1.5 hour drive [email protected] 208-731-9996 Office west and Pocatello, the state’s third largest city, is a 1.5 hour drive east. Salt Lake City is about 3 southernidaho.org hours southeast and northern Nevada is less than 1 hour south. Ideal interstate availability, local goods and products are only one day via truck to Oregon, Washington (and their seaports), Utah and Nevada, and two days to California, Colorado and Arizona. The topographic, geographic location, and seasonal variation in climate create a unique and varied natural Important Facts: environment which ranges from the scenic high alpine country in the north to the desolate lava • Southern Idaho was designated as a Top plains and desert mountains in the south, including world-famous ski resort, Sun Valley. U.S. Manufacturing Community by the U.S. Department of Commerce – one of four U.S. regions in the Food Manufacturing category (July 2015) Population: • Southern Idaho leads the state’s Twin Falls Jerome Burley/Cassia Rupert/Minidoka agribusiness industry by contributing well City 45,981 11,038 10,456 5,617 over half of the state’s nearly $9.7 billion County 80,914 22,514 23,540 20,323 agriculture receipts for 2014. Glenns Ferry/Elmore Wendell/Gooding • Idaho Power customers pay some of City 1,600 3,475 the lowest prices in the country for County 26,187 15,291 electricity – second lowest in the Pacific Northwest. -

KSD Active Vendors March 2020

KSD Active Vendors March 2020 Remit Name Remit City Remit State 4-H Youth Development Moscow ID A to B Motor Coach, LLC Rupert ID A to B Services LLC Rupert ID A-1 Towing & Heavy Haul LLC Twin Falls ID AAA Rental & Service Co Inc Jerome ID AAF Intermational Chicago IL Canyonside Enterprises Inc Jerome ID ABC Stamp, Signs, & Awards Boise ID AbleNet Inc Roseville MN Academic Innovations St George UT ACCO Engineered Systems Dept 10669 Glendale CA Accu Sales Jerome ID AccuCut Omaha NE Accurate Learning Systems Corporation Palo Alto CA ACP Direct Dallas TX Actuaries Northwest Issaquah WA ADA Sports Kansas City KS Addison Collision Repair Twin Falls ID ADP Lemco, Inc. Draper UT Adrienne Speirs . Advance Education Inc Atlanta GA Advanced Auto Atlanta GA Advanced Medical Personnel Services, Inc Pittsburgh PA Advanced Suspension Design Twin Falls ID Advantage Press Lisle IL AFPlanServ Oklahoma City OK Ageless Senior Citizens Inc Kimberly ID Agri-Service Inc Twin Falls ID Air Filter Sales Inc Eagle ID Air Filter Superstore Boise ID Air Quality Services Twin Falls ID Aire Filter Products Idaho Inc Phoenix AZ Airgas Intermountain Pasadena CA ALA-Amican Library Assn / Membership Chicago IL ALA-American Library Association Atlanta GA ALA-Magic Valley 4 Kids Twin Falls ID Alan Garrigues . Alberti Excavating Twin Falls ID Albertson's Twin Falls ID Alere Toxicology Dallas TX Alert Solutions Inc Cranston RI All Pro Sound Pensacola FL Alliance Family Services, Inc Twin Falls ID Allison Livingston Kimberly ID ALPHA Speech & Language Resources Mifflinville PA American Band Accessories Nixa MO American Fidelity Assurance Oklahoma City OK American Fidelity Assurance (Annuity) Oklahoma City OK American Fidelity Flex Acct. -

IDAHO LAND REPORT 2 0 2 0 Counties Included: Ada, Canyon, Bannock, Bonneville, Bingham, Insights Cassia, Jerome & Twin Falls » U.S

IDAHO LAND REPORT 2 0 2 0 Counties included: Ada, Canyon, Bannock, Bonneville, Bingham, Insights Cassia, Jerome & Twin Falls » U.S. home builders began Months Supply Level construction on homes at a seasonally-adjusted annual rate ADA COUNTY CANYON COUNTY of 1.496 million in July, up 22.6% New Construction 6.9 4.2 from the previous month and 23.4% Existing 7.5 4.9 from a year ago. The pace of home building is now 7% down from the pre-coronavirus high. *According to *According to Mortgage Bankers Association the U.S. Census Bureau Current Commercial Land Listings Average prices per acre by region » The overall Ada County July 2020 median sales price rose to $650,000 $290,000, which is an increase $600,000 of 11.7% compared to July 2019. $550,000 New homes made up 31.1% of all closed sales in July, with a median $500,000 sales price of $425,000, up 9.1% from July 2019. The median sales $450,000 Price has increased $18,157 since Q2 price for the existing homes rose as $400,000 2020 well, reaching $380,000 in July, an $350,000 increase of 15.2% year-over-year. MARKET AVERAGE *According to Boise Regional Realtors $300,000 PRICE $286,834 $250,000 Hot Spot $200,000 » Central Valley Plaza, located on the $150,000 corner of Chinden and Highway 16 in Meridian, is a new mixed- 773 923 ,836 $100,000 , use development that will feature $50,000 a unique combination of office, $254,804 $209 $442, $239 medical, flex, retail and senior living. -

Geologic Map of the Grangeville East Quadrangle, Idaho County, Idaho

IDAHO GEOLOGICAL SURVEY DIGITAL WEB MAP 86 MOSCOW-BOISE-POCATELLO SCHMIDT AND OTHERS Sixmile Creek pluton to the north near Orofino (Lee, 2004) and an age of indicate consistent dextral, southeast-side-up shear sense across this zone. REFERENCES GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE GRANGEVILLE EAST QUADRANGLE, IDAHO COUNTY, IDAHO CORRELATION OF MAP UNITS about 118 Ma in tonalite in the Hazard Creek complex to the south near Thus, the prebasalt history along this structure was likely oblique, dextral- McCall (Manduca and others, 1993). reverse shear that appears to offset the accreted terrane-continent suture Anderson, A.L., 1930, The geology and mineral resources of the region about zone by several miles in the adjoining Harpster quadrangle to the east. Orofino, Idaho: Idaho Geological Survey Pamphlet 34, 63 p. Quartz porphyry (Permian to Cretaceous)Quartz-phyric rock that is probably Artificial Alluvial Mass Movement Volcanic Rocks Intrusive Island-Arc Metavolcanic KPqp Barker, F., 1979, Trondhjemite: definition, environment, and hypotheses of origin, a shallow intrusive body. Highly altered and consists almost entirely of To the southeast of the Mt. Idaho shear zone, higher-grade, hornblende- Disclaimer: This Digital Web Map is an informal report and may be Deposits Deposits Deposits Rocks and Metasedimentary Rocks in Barker, F., ed., Trondhjemites, Dacites, and Related Rocks, Elsevier, New Keegan L. Schmidt, John D. Kauffman, David E. Stewart, quartz, sericite, and iron oxides. Historic mining activity at the Dewey Mine dominated gneiss and schist and minor marble (JPgs and JPm) occur along revised and formally published at a later time. Its content and format m York, p. -

Title Text Here Two Native Gardens with Pollinator Signs on the Idaho

Two Native Gardens with Pollinator Signs Titleon the text Idaho here Panhandle National Forests 2009 Accomplishments This project prepared and planted >40 species of plants native to North Idaho, Montana and eastern Washington in gardens at two offices of the Coeur d’Alene River Ranger District. One is home to plants which grow best in full sun; the other garden has partial shade. More than a dozen boy scouts prepared the garden plots by removing old junipers planted several years ago to border the district’s public parking lot. Now those spaces are full of native plants. Seedlings of native species were purchased from four native nurseries. Several species were grown from seed by volunteers including a master gardener. Some plants were transplanted from the national forest to the gardens. Over 200 volunteer hours were contributed to this project, most by youth ages 14-17. Two scouts made and installed custom plant identification signs from native materials. One will finish constructing the sign frames and install both 30” x 36” pollinator signs this fall at district offices in Figure 1. Pollinator sign at Fernan Ranger Station Coeur d’Alene and Smelterville. Gerry Queener donated 9 original pollinator photos, all taken in northern Idaho, to Year Awarded: initial award in 2009 illustrate the signs. Graphic artist Grady Myers designed Project completion: 2009 original artwork for the “pollinators” titles on the signs. The Report number: 1 of 1 WREN Foundation wrote a grant proposal to Red Willow Research (Twin Falls, ID.), which contributed an additional Expenditures (through 10/2009): $1,000 grant that funded one of our pollinator signs and one FY09 funding $3,500, expended $3,5000, $0 remaining for a popular BLM trail through a mature ponderosa pine .Total FS funding $3,500, total expended $3,500; forest east of Coeur d’Alene, Idaho.