Wood Biomass for Energy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Module III – Fire Analysis Fire Fundamentals: Definitions

Module III – Fire Analysis Fire Fundamentals: Definitions Joint EPRI/NRC-RES Fire PRA Workshop August 21-25, 2017 A Collaboration of the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI) & U.S. NRC Office of Nuclear Regulatory Research (RES) What is a Fire? .Fire: – destructive burning as manifested by any or all of the following: light, flame, heat, smoke (ASTM E176) – the rapid oxidation of a material in the chemical process of combustion, releasing heat, light, and various reaction products. (National Wildfire Coordinating Group) – the phenomenon of combustion manifested in light, flame, and heat (Merriam-Webster) – Combustion is an exothermic, self-sustaining reaction involving a solid, liquid, and/or gas-phase fuel (NFPA FP Handbook) 2 What is a Fire? . Fire Triangle – hasn’t change much… . Fire requires presence of: – Material that can burn (fuel) – Oxygen (generally from air) – Energy (initial ignition source and sustaining thermal feedback) . Ignition source can be a spark, short in an electrical device, welder’s torch, cutting slag, hot pipe, hot manifold, cigarette, … 3 Materials that May Burn .Materials that can burn are generally categorized by: – Ease of ignition (ignition temperature or flash point) . Flammable materials are relatively easy to ignite, lower flash point (e.g., gasoline) . Combustible materials burn but are more difficult to ignite, higher flash point, more energy needed(e.g., wood, diesel fuel) . Non-Combustible materials will not burn under normal conditions (e.g., granite, silica…) – State of the fuel . Solid (wood, electrical cable insulation) . Liquid (diesel fuel) . Gaseous (hydrogen) 4 Combustion Process .Combustion process involves . – An ignition source comes into contact and heats up the material – Material vaporizes and mixes up with the oxygen in the air and ignites – Exothermic reaction generates additional energy that heats the material, that vaporizes more, that reacts with the air, etc. -

Safety Data Sheet

Coghlan’s Magnesium Fire Starter #7870 SAFETY DATA SHEET This Safety Data Sheet complies with the Canadian Hazardous Product Regulations, the United States Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) Hazard Communication Standard, 29 CFR 1910 (OSHA HCS), and the European Union Directives. 1. Product and Supplier Identification 1.1 Product: Magnesium Fire Starter 1.2 Other Means of Identification: Coghlan’s #7870 1.3 Product Use: Fire starter 1.4 Restrictions on Use: None known 1.5 Producer: Coghlan’s Ltd., 121 Irene Street, Winnipeg, Manitoba Canada, R3T 4C7 Telephone: +1(204) 284-9550 Facsimile: +1(204) 475-4127 Email: [email protected] Supplier: As above 1.6 Emergencies: +1(877) 264-4526 2. Hazards Identification 2.1 Classification of product or mixture This product is an untested preparation. GHS classification for this preparation is based upon its use as a fire starter by making shavings and small particulate from the metal block. As shipped in mass form, this preparation is not considered to be a hazardous product and is not classifiable under the requirements of GHS. GHS Classification: Flammable Solids, Category 1 2.2 GHS Label Elements, including precautionary statements Pictogram: Signal Word: Danger Page 1 of 11 October 18, 2016 Coghlan’s Magnesium Fire Starter #7870 GHS Hazard Statements: H228: Flammable Solid GHS Precautionary Statements: Prevention: P210: Keep away from heat, hot surfaces, sparks, open flames and other ignition sources. No smoking. P280: Wear protective gloves, eye and face protection Response: P370+P378: In case of fire use water as first choice. Sand, earth, dry chemical, foam or CO2 may be used to extinguish. -

Operating and Maintaining a Wood Heater

OPERATING AND MAINTAINING A WOODHEATER FIREWOOD ASSOCIATION THE FIREWOODOF AUSTRALIA ASSOCIATION INC. OF AUSTRALIA INC. Building a wood fire Maintaining a wood heater For any fire to start and keep going three things are needed, Even in correctly operated wood heaters and fireplaces, some fuel, oxygen and heat. In wood fires the fuel is provided by the of the combustion gases will condense on the inside of the wood, the oxygen comes from the air, and the initial heat comes flue or chimney as a black tar-like substance called creosote. from burning paper or a fire lighter. In a going fire the heat is If this substance is allowed to build up it will restrict the air flow provided by the already burning wood. Without fuel, heat and in the heater or fireplace, reducing its efficiency. Eventually oxygen the fire will go out. When the important role of oxygen a build up of creosote can completely block the flue, making is understood, it is easy to see why you need plenty of air space around each piece of kindling when setting up the fire. the fire impossible to operate. One sign of a blocked flue is smoke coming into the room when you open the heater door. Kindling catches fire easily because it has a large surface Creosote appearing on the glass door is another indication area and small mass, which allows it to reach combustion that your heater is not working properly. Because creosote temperature quickly. The surface of a large piece of wood is flammable, if the chimney or flue gets hot enough the will not catch fire until it has been brought up to combustion creosote can catch alight, causing a dangerous chimney fire. -

FAOSTAT-Forestry Definitions

FOREST PRODUCTS DEFINITIONS General terms FAOSTAT - Forestry JOINT FOREST SECTOR QUESTIONNAIRE Item Item Code Definition code coniferous C Coniferous All woods derived from trees classified botanically as Gymnospermae, e.g. Abies spp., Araucaria spp., Cedrus spp., Chamaecyparis spp., Cupressus spp., Larix spp., Picea spp., Pinus spp., Thuja spp., Tsuga spp., etc. These are generally referred to as softwoods. non-coniferous NC Non-Coniferous All woods derived from trees classified botanically as Angiospermae, e.g. Acer spp., Dipterocarpus spp., Entandrophragma spp., Eucalyptus spp., Fagus spp., Populus spp., Quercus spp., Shorea spp., Swietonia spp., Tectona spp., etc. These are generally referred to as broadleaves or hardwoods. tropical NC.T Tropical Tropical timber is defined in the International Tropical Timber Agreement (1994) as follows: “Non-coniferous tropical wood for industrial uses, which grows or is produced in the countries situated between the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn. The term covers logs, sawnwood, veneer sheets and plywood. Plywood which includes in some measure conifers of tropical origin shall also be covered by the definition.” For the purposes of this questionnaire, tropical sawnwood, veneer sheets and plywood shall also include products produced in non-tropical countries from imported tropical roundwood. Please indicate if statistics provided under "tropical" in this questionnaire may include species or products beyond the scope of this definition. Year Data are requested for the calendar year (January-December) indicated. 2 Transactions FAOSTAT - Forestry JOINT FOREST SECTOR QUESTIONNAIRE Element Element Code Definition code 5516 Production Quantity Removals The volume of all trees, living or dead, that are felled and removed from the forest, other wooded land or other felling sites. -

The Role of Reforestation in Carbon Sequestration

New Forests (2019) 50:115–137 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11056-018-9655-3 The role of reforestation in carbon sequestration L. E. Nave1,2 · B. F. Walters3 · K. L. Hofmeister4 · C. H. Perry3 · U. Mishra5 · G. M. Domke3 · C. W. Swanston6 Received: 12 October 2017 / Accepted: 24 June 2018 / Published online: 9 July 2018 © Springer Nature B.V. 2018 Abstract In the United States (U.S.), the maintenance of forest cover is a legal mandate for federally managed forest lands. More broadly, reforestation following harvesting, recent or historic disturbances can enhance numerous carbon (C)-based ecosystem services and functions. These include production of woody biomass for forest products, and mitigation of atmos- pheric CO2 pollution and climate change by sequestering C into ecosystem pools where it can be stored for long timescales. Nonetheless, a range of assessments and analyses indicate that reforestation in the U.S. lags behind its potential, with the continuation of ecosystem services and functions at risk if reforestation is not increased. In this context, there is need for multiple independent analyses that quantify the role of reforestation in C sequestration, from ecosystems up to regional and national levels. Here, we describe the methods and report the fndings of a large-scale data synthesis aimed at four objectives: (1) estimate C storage in major ecosystem pools in forest and other land cover types; (2) quan- tify sources of variation in ecosystem C pools; (3) compare the impacts of reforestation and aforestation on C pools; (4) assess whether these results hold or diverge across ecore- gions. -

Learn the Facts: Fuel Consumption and CO2

Auto$mart Learn the facts: Fuel consumption and CO2 What is the issue? For an internal combustion engine to move a vehicle down the road, it must convert the energy stored in the fuel into mechanical energy to drive the wheels. This process produces carbon dioxide (CO2). What do I need to know? Burning 1 L of gasoline produces approximately 2.3 kg of CO2. This means that the average Canadian vehicle, which burns 2 000 L of gasoline every year, releases about 4 600 kg of CO2 into the atmosphere. But how can 1 L of gasoline, which weighs only 0.75 kg, produce 2.3 kg of CO2? The answer lies in the chemistry! Î The short answer: Gasoline contains carbon and hydrogen atoms. During combustion, the carbon (C) from the fuel combines with oxygen (O2) from the air to produce carbon dioxide (CO2). The additional weight comes from the oxygen. The longer answer: Î So it’s the oxygen from the air that makes the exhaust Gasoline is composed of hydrocarbons, which are hydrogen products heavier. (H) and carbon (C) atoms that are bonded to form hydrocarbon molecules (C H ). Air is primarily composed of X Y Now let’s look specifically at the CO2 reaction. This reaction nitrogen (N) and oxygen (O2). may be expressed as follows: A simplified equation for the combustion of a hydrocarbon C + O2 g CO2 fuel may be expressed as follows: Carbon has an atomic weight of 12, oxygen has an atomic Fuel (C H ) + oxygen (O ) + spark g water (H O) + X Y 2 2 weight of 16 and CO2 has a molecular weight of 44 carbon dioxide (CO2) + heat (1 carbon atom [12] + 2 oxygen atoms [2 x 16 = 32]). -

Renewable Energy Australian Water Utilities

Case Study 7 Renewable energy Australian water utilities The Australian water sector is a large emissions, Melbourne Water also has a Water Corporation are offsetting the energy user during the supply, treatment pipeline of R&D and commercialisation. electricity needs of their Southern and distribution of water. Energy use is These projects include algae for Seawater Desalination Plant by heavily influenced by the requirement treatment and biofuel production, purchasing all outputs from the to pump water and sewage and by advanced biogas recovery and small Mumbida Wind Farm and Greenough sewage treatment processes. To avoid scale hydro and solar generation. River Solar Farm. Greenough River challenges in a carbon constrained Solar Farm produces 10 megawatts of Yarra Valley Water, has constructed world, future utilities will need to rely renewable energy on 80 hectares of a waste to energy facility linked to a more on renewable sources of energy. land. The Mumbida wind farm comprise sewage treatment plant and generating Many utilities already have renewable 22 turbines generating 55 megawatts enough biogas to run both sites energy projects underway to meet their of renewable energy. In 2015-16, with surplus energy exported to the energy demands. planning started for a project to provide electricity grid. The purpose built facility a significant reduction in operating provides an environmentally friendly Implementation costs and greenhouse gas emissions by disposal solution for commercial organic offsetting most of the power consumed Sydney Water has built a diverse waste. The facility will divert 33,000 by the Beenyup Wastewater Treatment renewable energy portfolio made up of tonnes of commercial food waste Plant. -

Quality Wood Chip Fuel Depends on the Size of the Installation in Which It Is to Be Used: Pieter D

Harvesting / Transportation No. 6 The quality requirements for wood chip Quality wood chip fuel depends on the size of the installation in which it is to be used: Pieter D. Kofman 1 Small boilers (<250 kW) require a high quality wood fuel with a low moisture content (<30%) and a small, even chip with few, if any, Quality wood fuel depends mainly on: oversize or overlong particles. A • moisture content, low level of fungal spores is required. • particle size distribution, Medium boilers (250 kW<X<1 MW) • tree species, are more tolerant of moisture content (30-40%) and can handle a • bulk density, coarser chip than small boilers. • level of dust and fungal spores in the fuel, and Still, the amount of oversize and overlong particles should be • ash content. limited. A low level of fungal spores is required. Good quality wood chip fuel is produced by machines with sharp knives, with the ability to vary the size of chip produced to meet end-user specifications. Other Large boilers (>1 MW) are tolerant machines use hammers or flails to reduce particle size and produce hogfuel, of both moisture content (30-55%) and chip quality. The level of fungal which is unsuitable for use in small installations. Large installations can, spores can be higher because however, also have problems in handling and combusting hogfuel. For forest these installations usually take thinnings and other roundwood, chipping is the preferred option. their combustion air from the chip silo which reduces spore This note deals with wood chips only, even though there are other wood fuels, concentrations in and around the such as hogfuel, sawdust, firewood, peelings from fence posts, etc. -

Combustion Chemistry William H

Combustion Chemistry William H. Green MIT Dept. of Chemical Engineering 2014 Princeton-CEFRC Summer School on Combustion Course Length: 15 hrs June 2014 Copyright ©2014 by William H. Green This material is not to be sold, reproduced or distributed without prior written permission of the owner, William H. Green. 1 Combustion Chemistry William H. Green Combustion Summer School June 2014 2 Acknowledgements • Thanks to the following people for allowing me to show some of their figures or slides: • Mike Pilling, Leeds University • Hai Wang, Stanford University • Tim Wallington, Ford Motor Company • Charlie Westbrook (formerly of LLNL) • Stephen J. Klippenstein (Argonne) …and many of my hard-working students and postdocs from MIT 3 Overview Part 1: Big picture & Motivation Part 2: Intro to Kinetics, Combustion Chem Part 3: Thermochemistry Part 4: Kinetics & Mechanism Part 5: Computational Kinetics Be Prepared: There will be some Quizzes and Homework 4 Part 1: The Big Picture on Fuels and Combustion Chemistry 5 What is a Fuel? • Fuel is a material that carries energy in chemical form. • When the fuel is reacted (e.g. through combustion), most of the energy is released as heat • Though sometimes e.g. in fuel cells or flow batteries it can be released as electric power • Fuels have much higher energy densities than other ways of carrying energy. Very convenient for transportation. • The energy is released via chemical reactions. Each fuel undergoes different reactions, with different rates. Chemical details matter. 6 Transportation Fuel: Big Issues •People want, economy depends on transportation • Cars (growing rapidly in Asia) • Trucks (critical for economy everywhere) • Airplanes (growing rapidly everywhere) • Demand for Fuel is “Inelastic”: once they have invested in a vehicle, people will pay to fuel it even if price is high •Liquid Fuels are Best • Liquids Flow (solids are hard to handle!) • High volumetric and mass energy density • Easy to store, distribute. -

SHELTON RESEARCH, INC. 1517 Pacheco St

SHELTON RESEARCH, INC. 1517 Pacheco St. P.O. Box 5235 Santa Fe, NM 87502 505-983-9457 EVALUATim OF LOW-EMISSION WOOD STOVES by I Jay W. Shelton and Larry W. Gay Shelton Research, Inc. P.O. Box 5235 ! 1517 Pacheco Street Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501 [ June 23, 1986 FINAL REPORT I OON1RACT A3-122-32 Prepared for CALIFORNIA AIR RESOURCES BOARD P.O. Box 2815 1102 Q Street Sacramento, California 95812 Shelton Research, Ince Research Report No. 1086 I, TABLE CF CDmN.rS la PAGE 1' 1 LIST Clii' T~S••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• I~ LIST OF FIGURES •••••••••••••••••••••••••••• ii r } 1. SlM'v1ARY AND CINa.,USICNS •••••••••••••••••••• 1 ~- 2. RE~T1rns•••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 3 ! 3. I N'IRmJCTI. rn••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 4 4. APPLIANCE AND FUEL SELECTirn••••••••••••••• 5 5. 'IEa-IN"I oo_, JI'IIDAOI. •••.•••••...•.•••••.•••. 14 Test cycles •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 14 Installation••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 16 Stove Q?eration•••••••••••••••••••••••••• 16 Fuel Properties•••••••••••••••••••••••••• 16 Measursnent Methods •••••••••••••••••••••• 18 Data Acquisition and Processing•••••••••• 29 r; 6. RESlJI..,TS. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 30 J Introduction••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 30 Units for Fmissions •••••••••••••••••••••• 30 E:x: tra Tes ts •• ., •• "•••••••••••••••••••••••• 30 Particulate Matter ••••••••••••••••••••••• 31 Oeosote•••••• ., •••••••••••••••••••••••••• 32 P.AII. ••••••••••• o • •••••••••••••••••••••••• 32 l NOx •••••••••• t.10••·········· ............. 32 .Amoonia and cyanide•••••••••••••••••••••• -

The Opportunity of Cogeneration in the Ceramic Industry in Brazil – Case Study of Clay Drying by a Dry Route Process for Ceramic Tiles

CASTELLÓN (SPAIN) THE OPPORTUNITY OF COGENERATION IN THE CERAMIC INDUSTRY IN BRAZIL – CASE STUDY OF CLAY DRYING BY A DRY ROUTE PROCESS FOR CERAMIC TILES (1) L. Soto Messias, (2) J. F. Marciano Motta, (3) H. Barreto Brito (1) FIGENER Engenheiros Associados S.A (2) IPT - Instituto de Pesquisas Tecnológicas do Estado de São Paulo S.A (3) COMGAS – Companhia de Gás de São Paulo ABSTRACT In this work two alternatives (turbo and motor generator) using natural gas were considered as an application of Cogeneration Heat Power (CHP) scheme comparing with a conventional air heater in an artificial drying process for raw material in a dry route process for ceramic tiles. Considering the drying process and its influence in the raw material, the studies and tests in laboratories with clay samples were focused to investigate the appropriate temperature of dry gases and the type of drier in order to maintain the best clay properties after the drying process. Considering a few applications of CHP in a ceramic industrial sector in Brazil, the study has demonstrated the viability of cogeneration opportunities as an efficient way to use natural gas to complement the hydroelectricity to attend the rising electrical demand in the country in opposition to central power plants. Both aspects entail an innovative view of the industries in the most important ceramic tiles cluster in the Americas which reaches 300 million squares meters a year. 1 CASTELLÓN (SPAIN) 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1. The energy scenario in Brazil. In Brazil more than 80% of the country’s installed capacity of electric energy is generated using hydropower. -

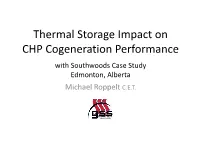

Thermal Storage Impact on CHP Cogeneration Performance with Southwoods Case Study Edmonton, Alberta Michael Roppelt C.E.T

Thermal Storage Impact on CHP Cogeneration Performance with Southwoods Case Study Edmonton, Alberta Michael Roppelt C.E.T. CHP Cogeneration Solar PV Solar Thermal Grid Supply Thermal Storage GeoExchange RenewableAlternative & LowEnergy Carbon Microgrid Hybrid ConventionalSystemSystem System Optional Solar Thermal Option al Solar PV CNG & BUILDING OR Refueling COMMUNITY Station CHP Cogeneration SCALE 8 DEVELOPMENT Hot Water Hot Water DHW Space Heating $ SAVINGS GHG OPERATING Thermal Energy Cool Water Exchange & Storage ElectricalMicro Micro-Grid-Grid Thermal Microgrid Moving Energy not Wasting Energy Natural Gas Combined Heat and Power (CHP) Cogeneration $350,000 2,500,000 kWh RETAILINPUT OUTPUT VALUE NATURAL GAS $400,000. $100,000.30,000 Gj (85% Efficiency) CHP $50,000 Cogeneration15,000 Energy Gj Technologies CHP Unit Sizing Poorly sized units will not perform optimally which will cancel out the benefits. • For optimal efficiency, CHP units should be designed to provide baseline electrical or thermal output. • A plant needs to operate as many hours as possible, since idle plants produce no benefits. • CHP units have the ability to modulate, or change their output in order to meet fluctuating demand. Meeting Electric Power Demand Energy Production Profile 700 Hourly Average 600 353 January 342 February 500 333 March 324 April 400 345 May 300 369 June 400 July 200 402 August 348 September 100 358 October 0 362 November 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 Meeting Heat Demand with CHP Cogeneration Energy Production Profile Heat Demand (kWh) Electric Demand (kWh) Cogen Heat (kWh) Waste Heat Heat Shortfall Useable Heat CHP Performance INEFFICIENCY 15% SPACE HEATING DAILY AND HEAT 35% SEASONAL ELECTRICAL 50% IMBALANCE 35% 50% DHW 15% Industry Studies The IEA works to ensure reliable, affordable and clean energy for its 30 member countries and beyond.