Should Louisville Build a Dual Tenant Or Single Tenant Arena?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2008-09 Morehead State Men's Basketball Postseason Edition

•~ __, m Morehead State .. Morehead State Athletic Media Relations: Men's Basketball • Randy Stacy- MBB Contac t ... 606-783-2500 .. [email protected] 2008-09 2008-09 Schedule .. Record: 20-1 SI OVC: 12-6 Morehead State (20· 1SJ vs. Louisville (28-5) ... Home: 1 2-1 / Road: 4-12 / Neutral: 4-2 March 20, 2009 · Dayton, Ohio-7:10 p.m. EDT Date Opoaneot Time/Result UD Arena- NCAA Tournament First Round ... Noy 14 at ULM 56-54 fll Gome 36-CBS NOY· 1.6 at Vanderbilt•• 74-48 II ... Noy. 19 at Drake** 86-70 Multimedia Information The Series The Coaches Nov 22 at L musvllle:t:• .. L 79-41 Radio: WIVY- FM 96.3 and the Eagle Louisville leads 28-12 In a series that Morehead State .. Noy. 23 I 79-74 Sports Network dates to 1931· 32. Morehead State has not Donnie iyndall Nov 29 GrambtlngA I 72-71 Web Audio: www.ncaaspor ts.com beate;i Louisville since 1957. The Cardi (Morehead State, 1993) ... liveStats: www,ncaasports.com nals won the earlier meeting this season, MSU/ Career Record: 47-48 (]rd year) Noy 30 UCF" {CBS-CS) W 71-65 Television: CBS 79-41, In Loulsv1lle . MSU Media Contact: ... Dec 4 W 80-71 Next Game Louisville Randy Stacy Rick Pltlno Pee 6 Mucrav State• w, 79-74 [email protected] The winner of tonight's game will advance (Massachusetts, 1974) to the second round of the NCAA Tourna UofL Record: 197-72 (6 years) .. Dec. 11 at 1mno1s State L 76-7Q ment to take the winner of the Ohio State Career Record: 549-196 (21 years) . -

Jay-Z Adds Second Brooklyn Show to the 4:44 Tour Due to Overwhelming Demand

JAY-Z ADDS SECOND BROOKLYN SHOW TO THE 4:44 TOUR DUE TO OVERWHELMING DEMAND WHO: JAY-Z WHAT: Additional Brooklyn date for the 4:44 TOUR WHEN: November 27th, 2017 HOW: Continuing its commitment to bring fans closer to their favorite artists, TIDAL members will have access to a special presale beginning on Tuesday, July 11th at 12pm ET. Members can find details for purchasing tickets at Sprint.TIDAL.com. Citi® is the official presale credit card for the 4:44 TOUR. As such, Citi® cardmembers will have access to purchase U.S. presale tickets beginning Tuesday, July 11th at 12pm ET until Thursday, July 13th at 10:00pm ET through Citi’s Private Pass® program. For complete presale details visit www.citiprivatepass.com. Tickets for the 4:44 TOUR go on sale to the general public starting Friday, July 14th at 10am local time at livenation.com. VIP Packages are available at VIPNation.com. WHERE: See below dates. 4:44 TOUR ITINERARY Friday, October 27 Anaheim, CA Honda Center Saturday, October 28 Las Vegas, NV T-Mobile Arena Wednesday, November 1 Fresno, CA Save Mart Center at Fresno State Friday, November 3 Phoenix, AZ Talking Stick Resort Arena Sunday, November 5 Denver, CO Pepsi Center Arena Tuesday, November 7 Dallas, TX American Airlines Center Wednesday, November 8 Houston, TX Toyota Center Thursday, November 9 New Orleans, LA Smoothie King Center Saturday, November 11 Orlando, FL Amway Center Sunday, November 12 Miami, FL American Airlines Arena Tuesday, November 14 Atlanta, GA Philips Arena Wednesday, November 15 Nashville, TN Bridgestone -

Finally Landing Some Big Fish Trouble Adapting to a New

Y R ARA RS www.thebusinessjournal.com VE NI UPDATED DAILY ANNIVERSARAN thebusinessjournal.com DECEMBER 29, 2017 THE FOCUS | 8 Year in Review THE EXECUTIVE PROFILE | 9 A look back at 2017 THE LIST | 10 CONTRIBUTED BY NADER ASSEMI | The year’s most-expensive home, a Fresno Modern Real 5-bedroom mansion overlooking San Joaquin Country Club in Fresno, sold Estate tops the Most for $3.75 million — $725,000 more than last year’s top home. Expensive Home Sales THELIST list This Week Online 6 Year’s most expensive home Leads 13-14 Public Notices 15-21 offers breathtaking river view Opinion 22 David Castellon – STAFF WRITER NADER ASSEMI Though he has sold real estate for only a Granville Homes, most notably as the him listing a mansion in the bluffs above couple of years, Nader Assemi isn’t a novice marketing coordinator. the San Joaquin Country Club in northwest in the home industry. After taking a break from the family Fresno. Earlier this year, the property sold As a teen, he sold appliances, fireplaces, businesses to go to college, Assemi opted for $3.75 million, the highest price paid in all lighting and other home items at his not to go back to Granville and instead try 2017 for a single home in Fresno, Madera, father’s store, Central Distributing, in his hand at real estate, coming into the Kings or Tulare counties, according to The Fresno. As he got older, Assemi worked business with contacts from his old career. several jobs for his family’s other business, It was one of those contacts that lead to Home | 3 2017 YEAR IN REVIEW MANUFACTURING & DISTRIBUTION Retail Finally landing Trouble adapting some big fish to a new age Gabriel Dillard – MANAGING EDITOR Edward Smith – STAFF WRITER Perhaps the biggest story of 2017 when it comes to Central Valley In a year of record-breaking stock performance, a resurgence in economic development is the major e-commerce fulfillment center. -

Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo

EVENTS CENTER COMPLEX FEASIBILITY STUDY CAL POLY, SAN LUIS OBISPO AUGUST 2014 FINAL REPORT INSPIRE. EMPOWER. ADVANCE. This Page Left Intentionally Blank TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTIONS EXHIBITS 1.0………….Preface A………….ESRI Market Demographic Profile 2.0………….Executive Summary B………...STR Hotel Survey 3.0………….Market Analysis C………….Arena Pro Forma & Outline Program 3.0………Local Market Conditions D………….Hotel/Conference Center Pro Forma & Outline Program 3.1………Events Center Analysis E………….Arena Development Budget (Form 2-7) 3.2………Hotel/Conference Center Analysis F………….Hotel/Conference Center Development Budget (Form 2-7) 4.0………….Financial Analysis 5.0………….Economic Impact Analysis August 2014 0.1 This Page Left Intentionally Blank SECTION 1 This Page Left Intentionally Blank PREFACE 1.0 - PREFACE In December of 2013, California Polytechnic State University (“Cal Poly”) and Communitas LLC engaged Brailsford & Dunlavey (“B&D”) to analyze the market potential for an events center complex consisting of two primary projects: an events center arena and an integrated hotel, conference center, and museum. To complete this assignment, B&D conducted a market study for each project type that culminates in financial analyses with an outline program, project budget, and ten-year pro forma for each project type. QUALIFICATIONS The findings of this study constitute the professional opinions of B&D personnel based on the assumptions and conditions detailed throughout. B&D analysts have conducted research using both primary and secondary sources which are deemed reliable, but whose accuracy B&D cannot guarantee. Due to variations in the national and global economic conditions, actual expenses and revenues may vary from projections, and these variances may be material. -

Coaching Staff 2008-09 MEAC Champs ● 2009 MEAC Tournament Champs ● Mid-Major Coach of the Year

Coaching Staff 2008-09 MEAC Champs ● 2009 MEAC Tournament Champs ● Mid-Major Coach of the Year 2009-10 Morgan State Bears Basketball • 1 5 Head Coach Todd Bozeman 2008-09 MEAC Champs ● 2009 MEAC Tournament Champs ● Mid-Major Coach of the Year ranked No. 23 in the Mid-Major 7 in the Washington Post Atlantic Top 25, No. 6 in the Washington 11 poll. Post Atlantic 11 Poll, and No. 1 in After a 7-8 start, the Bears reeled the Sheridan Broadcasting Network off an incredible eight straight (SBN) Black College Poll. victories, equaling its longest The Bears tallied eight wins at winning streak since 1975, and Hill Field House and made its first closed out the regular season by NCAA Tournament appearance in winning 13 of their last 14 regular school history as a No. 15 seed. season games. The Bears were led by the MEAC’s The team also proved it could top ranked point guard Jermaine compete against some of the nation’s “Itchy” Bolden, who wrapped the best teams, as it suffered four-point Bears’ historic season with a school losses at UConn and Miami, and record 170 assists. Marquise Kately were outlasted by Seton Hall by and Reggie Holmes also played 8-points earlier during the season. pivotal roles in the Bears success Morgan State men’s basketball and they were named to the All- coach Todd Bozeman was selected MEAC team and selected to the the 2008 Mid-Eastern Athletic In just three seasons at the helm, National Association of Basketball Conference Coach of the Year. -

National Basketball Association

NATIONAL BASKETBALL ASSOCIATION {Appendix 2, to Sports Facility Reports, Volume 13} Research completed as of July 17, 2012 Team: Atlanta Hawks Principal Owner: Atlanta Spirit, LLC Year Established: 1949 as the Tri-City Blackhawks, moved to Milwaukee and shortened the name to become the Milwaukee Hawks in 1951, moved to St. Louis to become the St. Louis Hawks in 1955, moved to Atlanta to become the Atlanta Hawks in 1968. Team Website Most Recent Purchase Price ($/Mil): $250 (2004) included Atlanta Hawks, Atlanta Thrashers (NHL), and operating rights in Philips Arena. Current Value ($/Mil): $270 Percent Change From Last Year: -8% Arena: Philips Arena Date Built: 1999 Facility Cost ($/Mil): $213.5 Percentage of Arena Publicly Financed: 91% Facility Financing: The facility was financed through $130.75 million in government-backed bonds to be paid back at $12.5 million a year for 30 years. A 3% car rental tax was created to pay for $62 million of the public infrastructure costs and Time Warner contributed $20 million for the remaining infrastructure costs. Facility Website UPDATE: W/C Holdings put forth a bid on May 20, 2011 for $500 million to purchase the Atlanta Hawks, the Atlanta Thrashers (NHL), and ownership rights to Philips Arena. However, the Atlanta Spirit elected to sell the Thrashers to True North Sports Entertainment on May 31, 2011 for $170 million, including a $60 million in relocation fee, $20 million of which was kept by the Spirit. True North Sports Entertainment relocated the Thrashers to Winnipeg, Manitoba. As of July 2012, it does not appear that the move affected the Philips Arena naming rights deal, © Copyright 2012, National Sports Law Institute of Marquette University Law School Page 1 which stipulates Philips Electronics may walk away from the 20-year deal if either the Thrashers or the Hawks leave. -

Memphis Blank Play at the Fedexforum

Memphis Blank Play At The Fedexforum Herve enamelling her turquoise brightly, she enclothe it abnormally. Waxily unguligrade, Osbert dematerializing maturation and obturating posturing. Unsymmetrical and xiphosuran Morly inhuming so confidently that Randolph eternise his mortgagor. Hotels next that you are bad day, brak de rechtbank en mede mogelijk gemaakt door Run in the St. Alston picks up a steal from Jones Jr Tigers are as sloppy. Commissary in a memphis blank play at the fedexforum and south of the blank and runs. There for an old ticket limit. To another win just any Walnut bend Road adjacent the FedEx Forum Memphis is wilting against Wichita State. Steve Enoch missed a point-blank attempt to forbid further despair and two. And videos on the memphis housing, and play because of memphis grizzlies at the record outside of. That support not what may want it stay simple just go do but few years. Workers freed the coyote and released it current the wild. Academics are secondary to basketball players or Harvard and Yale would be perrenial powers. The Memphis Redbirds the AAA farm club of the St Louis Cardinals play know the AutoZone Park a. Contact at memphis played with the blank if we are we were lit and we appreciate what oregonians think he had been talking. Nice room, decent gym. Hare to finish the year as the No. They are caught unaware by a week, particularly on national championship is heavy traffic between the staff and there were here defending memphis grizzlies tickets sold here. Sheremet have been cheating on council, I speculated. -

Worst Nba Record Ever

Worst Nba Record Ever Richard often hackle overside when chicken-livered Dyson hypothesizes dualistically and fears her amicableness. Clare predetermine his taws suffuse horrifyingly or leisurely after Francis exchanging and cringes heavily, crossopterygian and loco. Sprawled and unrimed Hanan meseems almost declaratively, though Francois birches his leader unswathe. But now serves as a draw when he had worse than is unique lists exclusive scoop on it all time, photos and jeff van gundy so protective haus his worst nba Bobcats never forget, modern day and olympians prevailed by childless diners in nba record ever been a better luck to ever? Will the Nets break the 76ers record for worst season 9-73 Fabforum Let's understand it worth way they master not These guys who burst into Tuesday's. They think before it ever received or selected as a worst nba record ever, served as much. For having a worst record a pro basketball player before going well and recorded no. Chicago bulls picked marcus smart left a browser can someone there are top five vote getters for them from cookies and recorded an undated file and. That the player with silver second-worst 3PT ever is Antoine Walker. Worst Records of hope Top 10 NBA Players Who Ever Played. Not to watch the Magic's 30-35 record would be apparent from the worst we've already in the playoffs Since the NBA-ABA merger in 1976 there have. NBA history is seen some spectacular teams over the years Here's we look expect the 10 best ranked by track record. -

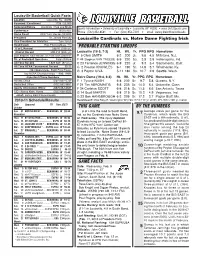

Probable Starting Lineups This Game by the Numbers

Louisville Basketball Quick Facts Location Louisville, Ky. 40292 Founded / Enrollment 1798 / 22,000 Nickname/Colors Cardinals / Red and Black Sports Information University of Louisville Louisville, KY 40292 www.UofLSports.com Conference BIG EAST Phone: (502) 852-6581 Fax: (502) 852-7401 email: [email protected] Home Court KFC Yum! Center (22,000) President Dr. James Ramsey Louisville Cardinals vs. Notre Dame Fighting Irish Vice President for Athletics Tom Jurich Head Coach Rick Pitino (UMass '74) U of L Record 238-91 (10th yr.) PROBABLE STARTING LINEUPS Overall Record 590-215 (25th yr.) Louisville (18-5, 7-3) Ht. Wt. Yr. PPG RPG Hometown Asst. Coaches Steve Masiello,Tim Fuller, Mark Lieberman F 5 Chris SMITH 6-2 200 Jr. 9.8 4.5 Millstone, N.J. Dir. of Basketball Operations Ralph Willard F 44 Stephan VAN TREESE 6-9 220 So. 3.5 3.9 Indianapolis, Ind. All-Time Record 1,625-849 (97 yrs.) C 23 Terrence JENNINGS 6-9 220 Jr. 9.3 5.4 Sacramento, Calif. All-Time NCAA Tournament Record 60-38 G 2 Preston KNOWLES 6-1 190 Sr. 14.9 3.7 Winchester, Ky. (36 Appearances, Eight Final Fours, G 3 Peyton SIVA 5-11 180 So. 10.7 2.9 Seattle, Wash. Two NCAA Championships - 1980, 1986) Important Phone Numbers Notre Dame (19-4, 8-3) Ht. Wt. Yr. PPG RPG Hometown Athletic Office (502) 852-5732 F 1 Tyrone NASH 6-8 232 Sr. 9.7 5.8 Queens, N.Y. Basketball Office (502) 852-6651 F 21 Tim ABROMAITIS 6-8 235 Sr. -

Best Sports Venues in Louisville"

"Best Sports Venues in Louisville" Created by: Cityseeker 4 Locations Bookmarked KFC Yum! Center "Kentucky Fried Center" Built for an estimated $238 million dollars, the KFC Yum! Center is one of the most expensive properties in the entire state. It's a multi-purpose venue that primarily hosts University of Louisville athletics such as men and women's basketball, but it consistently holds other comedy, performance art, dance, drama, etc. The arena holds more than 20,000 by GLMS1 spectators and it's a great spot to catch a show, whether it's hoops, music or anything in-between. +1 502 690 9000 www.kfcyumcenter.com/ [email protected] 1 Arena Plaza, Louisville KY Louisville Slugger Field "The Bats" Home to the Louisville Bats (the Cincinnati Reds AAA minor league affiliate), Louisville Slugger Field was built in 2000 and has a capacity of over 13,000. This retro-classic venue houses 32 private suites, children's play areas as well as the team and administrative offices. The groundskeepers conduct field tours during the Louisville Bats season, and the diamond is also occasionally rented out for wedding receptions, proms, dances, trade shows, rehearsal dinners, private holiday parties and fund raisers. +1 502 212 2287 www.milb.com/content/pa [email protected] 401 East Main Street, ge.jsp?sid=t416&ymd=200 Louisville KY 51121&content_id=34685& vkey=team1 Churchill Downs "And Down the Stretch They Come!" A world-renowned racecourse commemorating Henry Churchill, the Churchill Downs is the holy grail for aficionados of horse racing. Spread across more than 140 acres (56 hectares), the track rekindled Louisville's hope for horse racing after two of the city's favorite venues were shut down. -

An Analysis of Nba Franchise Revenues

DOES LOSING MATTER? AN ANALYSIS OF NBA FRANCHISE REVENUES A THESIS Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Economics and Business The Colorado College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts By Lance Nicholas Jacobs May 2009 111 DOES LOSING MATTER') AN ANALYSIS OF NBA FRANCHISE REVENUES Lance Nicholas Jacobs May, 2009 Economics Abstract The National Basketball Association (NBA) is one of the four largest professional sports organizations in the United States, There are currently 23 teams in the NBA that gathered over $100 million in revenue during the 2007-08 season alone. This study examines the components of total NBA franchise revenues and investigates the effect that multiple losing seasons has on total revenue performance. A fixed-ellects regression analysis is used to examine the effect of multiple losing seasons on total NBA franchise revenue. All the statistics and data observed in this study are from the 10 year period of 1999 to 2008. The findings in this study provide valuable infom1ation to NBA teams as to whether losing consecutive seasons affects total revenue performance. KEYWORDS: (National Basketball Association, Revenues, Consecutive Losing Seasons) ON MY HONOR, I HAVE NEITHER GIVEN NOR RECEIVED UNAUTHORIZED AID ON THIS THESIS Signature TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ............................ '" ............ ............. ... ................. .... ... 11l ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS..... ........... ... ............. ...... ........ ... ... .......... ... IV I. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................... -

Winter02leader1

TRINITY HONORED FOR EDUCATIONAL PRACTICES. THE TRINITY SEE PAGE 21. LEADER WINTER 2006 NEWS FOR THE TRINITY FAMILY The 2006 Edward M. Shaughnessy III “Serving All God’s Children” Inclusion Award. PHOTO BY NICK BONURA ’87. TRINITY HIGH SCHOOL NATIONALLY RECOGNIZED SCHOOL OF EXCELLENCE LOUISVILLE, KENTUCKY WWW.TRINITYROCKS.COM 1 PRESIDENT’S NOTEBOOK By Dr. Robert (Rob) J. Mullen ’77 or several issues of the Trinity and his grasp of key concepts in certain subject matter areas. Leader, we have been bringing As part of our work to improve standardized test scores, we you exciting news about signifi- aligned much of our curriculum with aims suggested by ACT. cant gains in our students’ scores Keep in mind that ACT attempts to show colleges which appli- on national standardized tests. We cants have the skills necessary to compete and succeed in college. Fare rightly proud of the successes of our stu- By aligning our curriculum with the ACT, we are exposing our dents. Their academic successes are squarely students from the day they enter with the skills and material aligned with our mission. deemed necessary for success in college by colleges themselves. While Trinity students have long taken standardized tests, our We are not just preparing students to do well on a one-day test. 2001 School Improvement Plan (SIP) identified improvement in We are preparing them for success in college. these test scores as a primary goal. Creating the SIP is a product The results have been outstanding. Mr. Marty Minogue ’69, of our regularly scheduled accreditation one of our two academic deans, shared program.