Memphis State: Quite a Commitment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Men's Basketball Coaching Records

MEN’S BASKETBALL COACHING RECORDS Overall Coaching Records 2 NCAA Division I Coaching Records 4 Coaching Honors 31 Division II Coaching Records 36 Division III Coaching Records 39 ALL-DIVISIONS COACHING RECORDS Some of the won-lost records included in this coaches section Coach (Alma Mater), Schools, Tenure Yrs. WonLost Pct. have been adjusted because of action by the NCAA Committee 26. Thad Matta (Butler 1990) Butler 2001, Xavier 15 401 125 .762 on Infractions to forfeit or vacate particular regular-season 2002-04, Ohio St. 2005-15* games or vacate particular NCAA tournament games. 27. Torchy Clark (Marquette 1951) UCF 1970-83 14 268 84 .761 28. Vic Bubas (North Carolina St. 1951) Duke 10 213 67 .761 1960-69 COACHES BY WINNING PERCENT- 29. Ron Niekamp (Miami (OH) 1972) Findlay 26 589 185 .761 1986-11 AGE 30. Ray Harper (Ky. Wesleyan 1985) Ky. 15 316 99 .761 Wesleyan 1997-05, Oklahoma City 2006- (This list includes all coaches with a minimum 10 head coaching 08, Western Ky. 2012-15* Seasons at NCAA schools regardless of classification.) 31. Mike Jones (Mississippi Col. 1975) Mississippi 16 330 104 .760 Col. 1989-02, 07-08 32. Lucias Mitchell (Jackson St. 1956) Alabama 15 325 103 .759 Coach (Alma Mater), Schools, Tenure Yrs. WonLost Pct. St. 1964-67, Kentucky St. 1968-75, Norfolk 1. Jim Crutchfield (West Virginia 1978) West 11 300 53 .850 St. 1979-81 Liberty 2005-15* 33. Harry Fisher (Columbia 1905) Fordham 1905, 16 189 60 .759 2. Clair Bee (Waynesburg 1925) Rider 1929-31, 21 412 88 .824 Columbia 1907, Army West Point 1907, LIU Brooklyn 1932-43, 46-51 Columbia 1908-10, St. -

1997 Induction Class Larry Bird, Indiana State Hersey Hawkins

1997 Induction Class Institutional Great -- Carole Baumgarten, Drake Larry Bird, Indiana State Lifetime Achievement -- Duane Klueh, Indiana State Hersey Hawkins, Bradley Paul Morrison Award -- Roland Banks, Wichita State Coach Henry Iba, Oklahoma A&M Ed Macauley, Saint Louis 2007 Induction Class Oscar Robertson, Cincinnati Jackie Stiles, Missouri State Dave Stallworth, Wichita State Wes Unseld, Louisville 2008 Induction Class Paul Morrison Award -- Paul Morrison, Drake Bob Harstad, Creighton Kevin Little, Drake 1998 Induction Class Ed Jucker, Cincinnati Bob Kurland, Oklahoma A&M Institutional Great -- A.J. Robertson, Bradley Chet Walker, Bradley Lifetime Achievement -- Jim Byers, Evansville Xavier McDaniel, Wichita State Lifetime Achievement -- Jill Hutchison, Illinois State Lifetime Achievement -- Kenneth Shaw, Illinois State Paul Morrison Award -- Mark Stillwell, Missouri State Institutional Great -- Doug Collins, Illinois State Paul Morrison Award -- Dr. Lee C. Bevilacqua, Creighton 2009 Induction Class Junior Bridgeman, Louisville 1999 Induction Class John Coughlan, Illinois State Antoine Carr, Wichita State Eddie Hickey, Creighton/Saint Louis Joe Carter, Wichita State Institutional Great -- Lorri Bauman, Drake Melody Howard, Missouri State Lifetime Achievement -- John Wooden, Indiana State Holli Hyche, Indiana State Lifetime Achievement -- John L. Griffith, Drake Paul Morrison Award -- Glen McCullough, Bradley Paul Morrison Award -- Jimmy Wright, Missouri State 2000 Induction Class 2010 Induction Class Cleo Littleton, Wichita State -

Georgia Tech Basketball 2016-17

2016-17 GEORGIA TECH BASKETBALL GAME NOTES @GTMBB • @GTJOSHPASTNER GEORGIA TECH BASKETBALL 2016-17 ACC Champions 1985, 1990, 1993 • Final Four 1990, 2004 • 16 NCAA Tournament appearances GEORGIA TECH (15-10, 6-6 ACC) vs. MIAMI (16-8, 6-6 ACC) 2016-17 Schedule/Results GAME 26 • February 15, 2017 • 8 p.m. ET • Watsco Center • Coral Gables, Fla. N5 SHORTER (exhibition) W, 95-87 (ot) N11 TENNESSEE TECH W, 70-55 Tech Back on the Road to Visit Miami GAME INFORMATION N14 SOUTHERN W, 77-62 Georgia Tech continues the back half of its Atlantic Coast Site Coral Gables, Fla. N18 OHIO L, 61-67 Conference schedule Wednesday night when it visits Miami for an 8 p.m. regionally-televised game at the Watsco Center in Venue Watsco Center (7,972) N22 SAM HOUSTON STATE W, 81-73 Coral Gables, Fla. Series vs. Miami Miami leads, 5-4 N26 TULANE W, 82-68 Tech (15-10, 6-6 ACC), which has defi ed pre-season On the road Tech leads, 5-2 N29 at Penn State L, 60-67 projections in its fi rst season under head coach Josh Pastner, Last meeting 2/27/16, Tech won 76-71 in Chestnut Hill D3 at Tennessee L, 58-81 resumed its ACC schedule Saturday with a 65-54 win over GEORGIA TECH D7 at VCU W, 76-73 (ot) Boston College at home. The Yellow Jackets, 2-7 on the road D18 ALCORN STATE W, 74-50 this season, including a win at NC State on Jan. 15, enter this 2016-17 Rankings (AP/coaches/RPI) nr / nr / 77 D20 GEORGIA L, 43-60 week’s games tied for eighth place in the ACC standings with the 2016-17 Record 15-10 (13-3 home, 2-7 away, 0-0 neutral) D22 WOFFORD W, 76-72 Hurricanes and Virginia Tech. -

2008-09 Morehead State Men's Basketball Postseason Edition

•~ __, m Morehead State .. Morehead State Athletic Media Relations: Men's Basketball • Randy Stacy- MBB Contac t ... 606-783-2500 .. [email protected] 2008-09 2008-09 Schedule .. Record: 20-1 SI OVC: 12-6 Morehead State (20· 1SJ vs. Louisville (28-5) ... Home: 1 2-1 / Road: 4-12 / Neutral: 4-2 March 20, 2009 · Dayton, Ohio-7:10 p.m. EDT Date Opoaneot Time/Result UD Arena- NCAA Tournament First Round ... Noy 14 at ULM 56-54 fll Gome 36-CBS NOY· 1.6 at Vanderbilt•• 74-48 II ... Noy. 19 at Drake** 86-70 Multimedia Information The Series The Coaches Nov 22 at L musvllle:t:• .. L 79-41 Radio: WIVY- FM 96.3 and the Eagle Louisville leads 28-12 In a series that Morehead State .. Noy. 23 I 79-74 Sports Network dates to 1931· 32. Morehead State has not Donnie iyndall Nov 29 GrambtlngA I 72-71 Web Audio: www.ncaaspor ts.com beate;i Louisville since 1957. The Cardi (Morehead State, 1993) ... liveStats: www,ncaasports.com nals won the earlier meeting this season, MSU/ Career Record: 47-48 (]rd year) Noy 30 UCF" {CBS-CS) W 71-65 Television: CBS 79-41, In Loulsv1lle . MSU Media Contact: ... Dec 4 W 80-71 Next Game Louisville Randy Stacy Rick Pltlno Pee 6 Mucrav State• w, 79-74 [email protected] The winner of tonight's game will advance (Massachusetts, 1974) to the second round of the NCAA Tourna UofL Record: 197-72 (6 years) .. Dec. 11 at 1mno1s State L 76-7Q ment to take the winner of the Ohio State Career Record: 549-196 (21 years) . -

2010-11 NCAA Men's Basketball Records

Coaching Records All-Divisions Coaching Records ............... 2 Division I Coaching Records ..................... 3 Division II Coaching Records .................... 24 Division III Coaching Records ................... 26 2 ALL-DIVISIONS COACHING RECORDS All-Divisions Coaching Records Some of the won-lost records included in this coaches section have been Coach (Alma Mater), Schools, Tenure Yrs. Won Lost Pct. adjusted because of action by the NCAA Committee on Infractions to forfeit 44. Don Meyer (Northern Colo. 1967) Hamline 1973-75, or vacate particular regular-season games or vacate particular NCAA tourna- Lipscomb 76-99, Northern St. 2000-10 ........................... 38 923 324 .740 ment games. The adjusted records for these coaches are listed at the end of 45. Al McGuire (St. John’s [NY] 1951) Belmont Abbey the longevity records in this section. 1958-64, Marquette 65-77 .................................................... 20 405 143 .739 46. Jim Boeheim (Syracuse 1966) Syracuse 1977-2010* ..... 34 829 293 .739 47. David Macedo (Wilkes 1996) Va. Wesleyan 2001-10* ... 10 215 76 .739 48. Phog Allen (Kansas 1906) Baker 1906-08, Haskell 1909, Coaches by Winning Percentage Central Mo. 13-19, Kansas 08-09, 20-56 .......................... 48 746 264 .739 49. Emmett D. Angell (Wisconsin) Wisconsin 1905-08, (This list includes all coaches with a minimum 10 head coaching seasons at NCAA Oregon St. 09-10, Milwaukee 11-14 ................................. 10 113 40 .739 schools regardless of classification.) 50. Everett Case (Wisconsin 1923) North Carolina St. 1947-65 ................................................... 19 377 134 .738 Coach (Alma Mater), Schools, Tenure Yrs. Won Lost Pct. * active; # Keogan’s winning percentage includes three ties. 1. Clair Bee (Waynesburg 1925) Rider 1929-31, Long Island 32-43, 46-51 ...................................................... -

Dr. James Naismith's 13 Original Rules of Basketball

DR. JAMES NAISMITH’S 13 ORIGINAL RULES OF BASKETBALL 1. The ball may be thrown in any direction with one or both hands. 2. The ball may be batted in any direction with one or both hands (never with the fist). 3. A player cannot run with the ball. The player must throw it from the spot on which he catches it, allowance to be made for a man who catches the ball when running at a good speed. 4. The ball must be held in or between the hands; the arms or body must not be used for holding it. 5. No shouldering, holding, pushing, tripping, or striking in any way the person of an opponent shall be allowed; the first infringement of this rule by any person shall count as a foul, the second shall disqualify him until the next goal is made, or if there was evident intent to injure the person, for the whole of the game, no substitute allowed. 6. A foul is striking at the ball with the fist, violation of rules 3 and 4, and such as described in rule 5. 7. If either side makes three consecutive fouls, it shall count a goal for the opponents (consecutive means without the opponents in the meantime making a foul). 8. A goal shall be made when the ball is thrown or batted from the grounds into the basket and stays there, providing those defending the goal do not touch or disturb the goal. If the ball rests on the edge and the opponent moves the basket it shall count as a goal. -

University of Cincinnati News Record. Friday, February 2, 1968. Vol. LV

\LI T , Vjb, i ;-/ Cineinneti, Ohio; Fr~day, February 2, 1968' No. 26 Tickets. For Mead Lectilres ..". liM,ore.ea. H' d''Sj·.L~SSI., .' F"eet...-< II Cru~cialGame.~ Gr~atestNeed'Of Young; Comments -MargQret Mead Are Ava'ilab'le by Alter Peerless '\... that the U.S. was fighting an evil Even before the Bearcatsget enemy, but now-people can see "In the, past fifty years there a chance to recover from the'" for themselves that in' war both has been too much use of feet, sides kill and mutilate other peo- _ shell shock of two conference and not enough use' of heads," ple. road loses in a row, tihey baY~,to -said Dr: Margaret Mead, inter- Another reason this generation play 'the most 'Crucial' game' of nationally kn'own· anthropologist, is unhappy is because the num- in her lecture at the YMCA.'last bers involved are smaller. In the yea!,~at Louisville. Tuesday., . Wednesday n i gh t's Bradley World War II, the Americans had Dr. Mead .spoke on "College no sympathy for war victims. game goes down as' a wasted ef- Students' Disillusionment: Viet- They could not comprehend the fort. Looking strong at the begin- nam War and National Service." fact that six' .million Jews were· ningthe 'Cats faded in the final She said that this is not the first ' killed, or that an entire city was period when 'young people have wiped out. The horror of World minutes, missing several shots. , demonstrated for 'good causes. Jim Ard played welleonsidering War II was so great, America There have' been peace marches, could not react to it. -

University of Cincinnati News Record. Thursday, January 26, 1967. Vol

State· Affiliation Proposed; ,UC: To Benefit Financially by Peter Franklin "The UC students.would be bene- fitted because of Iower fees coup- A plan proposin-g state affilia- led' with broader graduate and tion for UC has 'received the sup- professional offerings. The bene- port of the Ohio Board of Regents. fit to' the University would come The University would continue I from the acquisition ,of a broader under local control and retain its fina~cial base without the loss of' municipal status, but the accept- local ties and support." ance of the- proposal would result Dr.: Langsam explained that in greatly expanded financial aid ' "the City of Cincinnati would reap or the University. benefit from the proposal because l:owerTu.itlonFees of \ the lower instructional fees The most immediate benefit. to made available to its citizens as . ,,', . i '. .~'i 1...b .•...;;0. i " 'U\e uc student would be a drop in well as the millions of new -dollars that would flow into the. city ec- ,ordie Beats AII-Ameri~ci1" es:JtO?M~~~;sa~:6~iOcr.i~~i~~n.a:~:onomy., The city also would bene- r- G ,-, " . \i ~~- ~~ commenting on the proposed - fit from having a University that _ --"" " " ....• . •..•• plan Dr. Walter G. Langsam, UC was - better able to respond to f '" .. - '._, .' . ': '.~ . President, explained that the plan community. needs for 'expanded Later Drops No ..2..Lou. vOre ,. for state affiliation would-benefit and newprograms." , the students, the university, the "The state itself also would by Mike Kelly city and -the state. benefit because it means imple- University of Louisville's Cardi- menting the Regents' master plan nals could, take a tip from the in Southwestern Ohio at consider- Pinkerton police agency: the ,way F~iday/s Concert ably less expense than the· es- to cover Gordie Smith is to put tablishment of a new state uni- three men on him. -

The NCAA News, Rep

The NCAA Official Publication of the National Collegiate Athletic Association March 13,1991, Volume 28 Number 11 Division I commissioners back enforcement process Commissioners of the nation’s ident Thomas E. Yeager, commis- whelmingly supports the NCAA’s port for the NCAA’s program. The NCAA enforcement pro- Division I athletics conferences an- sioner of the Colonial Athletic process and the penalties that have “Accordingly, the commissioners gram and procedures have been nounced March 13 their strong en- Association, in forwarding the state- been levied. Unfortunately, repre- believed it was time to make a commended and supported by the dorsement of the NCAA enforce- ment to NCAA Executive Director sentatives of institutions found to statement supporting the NCAA’s Collegiate Commissioners Associa- ment program. Richard D. Schultz, said: have committed violations often process and reminding the mem- tion and University Commissioners The joint announcement was “The members of the Collegiate criticize the Association and its bership and the public that the Association, the organizations of made by the Collegiate Commis- Commissioners Association and Uni- procedures in an attempt to con- NCAA is a body of institutions, and the chief executive officers of the sioners Association and University versity Commissioners Association vince their fans that they are de- it is the constant element in the nation’s major-college conferences. Commissioners Association, which wished to express their disagreement fending the institution against the athletics program-the institu- The commissioners noted the com- represent all of the 36 conferences in with criticism of the NCAA cn- charges, regardless of whether those tion- that must be held accounta- plaints most often assertions that Division I of the NCAA. -

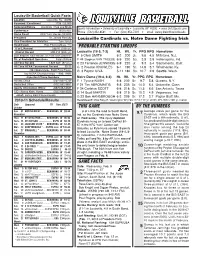

Probable Starting Lineups This Game by the Numbers

Louisville Basketball Quick Facts Location Louisville, Ky. 40292 Founded / Enrollment 1798 / 22,000 Nickname/Colors Cardinals / Red and Black Sports Information University of Louisville Louisville, KY 40292 www.UofLSports.com Conference BIG EAST Phone: (502) 852-6581 Fax: (502) 852-7401 email: [email protected] Home Court KFC Yum! Center (22,000) President Dr. James Ramsey Louisville Cardinals vs. Notre Dame Fighting Irish Vice President for Athletics Tom Jurich Head Coach Rick Pitino (UMass '74) U of L Record 238-91 (10th yr.) PROBABLE STARTING LINEUPS Overall Record 590-215 (25th yr.) Louisville (18-5, 7-3) Ht. Wt. Yr. PPG RPG Hometown Asst. Coaches Steve Masiello,Tim Fuller, Mark Lieberman F 5 Chris SMITH 6-2 200 Jr. 9.8 4.5 Millstone, N.J. Dir. of Basketball Operations Ralph Willard F 44 Stephan VAN TREESE 6-9 220 So. 3.5 3.9 Indianapolis, Ind. All-Time Record 1,625-849 (97 yrs.) C 23 Terrence JENNINGS 6-9 220 Jr. 9.3 5.4 Sacramento, Calif. All-Time NCAA Tournament Record 60-38 G 2 Preston KNOWLES 6-1 190 Sr. 14.9 3.7 Winchester, Ky. (36 Appearances, Eight Final Fours, G 3 Peyton SIVA 5-11 180 So. 10.7 2.9 Seattle, Wash. Two NCAA Championships - 1980, 1986) Important Phone Numbers Notre Dame (19-4, 8-3) Ht. Wt. Yr. PPG RPG Hometown Athletic Office (502) 852-5732 F 1 Tyrone NASH 6-8 232 Sr. 9.7 5.8 Queens, N.Y. Basketball Office (502) 852-6651 F 21 Tim ABROMAITIS 6-8 235 Sr. -

Best Sports Venues in Louisville"

"Best Sports Venues in Louisville" Created by: Cityseeker 4 Locations Bookmarked KFC Yum! Center "Kentucky Fried Center" Built for an estimated $238 million dollars, the KFC Yum! Center is one of the most expensive properties in the entire state. It's a multi-purpose venue that primarily hosts University of Louisville athletics such as men and women's basketball, but it consistently holds other comedy, performance art, dance, drama, etc. The arena holds more than 20,000 by GLMS1 spectators and it's a great spot to catch a show, whether it's hoops, music or anything in-between. +1 502 690 9000 www.kfcyumcenter.com/ [email protected] 1 Arena Plaza, Louisville KY Louisville Slugger Field "The Bats" Home to the Louisville Bats (the Cincinnati Reds AAA minor league affiliate), Louisville Slugger Field was built in 2000 and has a capacity of over 13,000. This retro-classic venue houses 32 private suites, children's play areas as well as the team and administrative offices. The groundskeepers conduct field tours during the Louisville Bats season, and the diamond is also occasionally rented out for wedding receptions, proms, dances, trade shows, rehearsal dinners, private holiday parties and fund raisers. +1 502 212 2287 www.milb.com/content/pa [email protected] 401 East Main Street, ge.jsp?sid=t416&ymd=200 Louisville KY 51121&content_id=34685& vkey=team1 Churchill Downs "And Down the Stretch They Come!" A world-renowned racecourse commemorating Henry Churchill, the Churchill Downs is the holy grail for aficionados of horse racing. Spread across more than 140 acres (56 hectares), the track rekindled Louisville's hope for horse racing after two of the city's favorite venues were shut down. -

DOC SADLER HEAD COACH | FOURTH YEAR | ARKANSAS, 1982 | RECORD at NEBRASKA: 55-40 the Nebraska Program Is Not Where Doc Sadler Wants It to Be

DOC SADLER HEAD COACH | FOURTH YEAR | ARKANSAS, 1982 | RECORD AT NEBRASKA: 55-40 The Nebraska program is not where Doc Sadler wants it to be. Despite the Huskers’ many successes in each of his first three years in Lincoln, the energetic and fiery mentor has bigger goals in mind that include winning championships and reaching heights THE SADLER FILE Full Name: Kenneth Lee Sadler never before seen in basketball in the Cornhusker State. Date of Birth: June 12, 1960 Hometown: Greenwood, Ark. Family: Wife, Tonya; Sons, Landon (16) He understands the hurdles and knows there is still a long way and Matthew (13) Education: Bachelors of Science, Arkansas, 1982; Masters of Science, to go to put those goals within reach. But by historical standards, Northeastern State, 1991 HEAD COACHING EXPERIENCE Sadler is exceeding expectations at an unprecedented rate and Nebraska, 2006-present; UTEP, 2004-06; quickly making believers out of fans and critics alike by showing Arkansas-Fort Smith, 1998-2003 ASSISTANT COACHING EXPERIENCE that his goals can be reached. Arkansas, 1982-85; Lamar, 1985-86; Houston, 1986; Chicago State, 1987-88; Arkansas-Fort Smith, 1988-91; Texas Nebraska never had a coach that has been the cornerstone for Sadler’s Alongside Sadler’s tradition of success, Tech, 1991-94; Arizona State, 1994-97; pushed it to at least 17 victories in each coaching career since he got into the his other impressive personal traits Arkansas-Fort Smith, 1997-98; UTEP, of his first three years on the sideline business in the early 1980s at Arkansas. – the charismatic personality, energy, 2003-04 until Sadler arrived in Lincoln before It’s a career that includes an outstanding passion and workmanlike approach to the 2006-07 season.