Sooke Bear-Safe Waste Management Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plan Employers

Plan Employers 18th Street Community Care Society 211 British Columbia Services Society 28th Avenue Homes Ltd 4347 Investments Ltd. dba Point Grey Private Hospital 484017 BC Ltd (dba Kimbelee Place) 577681 BC Ltd. dba Lakeshore Care Centre A Abilities Community Services Acacia Ty Mawr Holdings Ltd Access Human Resources Inc Active Care Youth and Adult Services Ltd Active Support Against Poverty Housing Society Active Support Against Poverty Society Age Care Investment (BC) Ltd AIDS Vancouver Society AiMHi—Prince George Association for Community Living Alberni Community and Women’s Services Society Alberni-Clayoquot Continuing Care Society Alberni-Clayoquot Regional District Alouette Addiction Services Society Amata Transition House Society Ambulance Paramedics of British Columbia CUPE Local 873 Ann Davis Transition Society Archway Community Services Society Archway Society for Domestic Peace Arcus Community Resources Ltd Updated September 30, 2021 Plan Employers Argyll Lodge Ltd Armstrong/ Spallumcheen Parks & Recreation Arrow and Slocan Lakes Community Services Arrowsmith Health Care 2011 Society Art Gallery of Greater Victoria Arvand Investment Corporation (Britannia Lodge) ASK Wellness Society Association of Neighbourhood Houses of British Columbia AVI Health & Community Services Society Avonlea Care Centre Ltd AWAC—An Association Advocating for Women and Children AXIS Family Resources Ltd AXR Operating (BC) LP Azimuth Health Program Management Ltd (Barberry Lodge) B BC Council for Families BC Family Hearing Resource Society BC Institute -

BYTAW NO.2024 WHEREAS Council May, Pursuant To

THE CORPORATION OF THE DISTRICT OF CENTRAL SAANICH BYTAW NO.2024 A BYLAW TO ESTABLISH A SCHEME FOR INTERCOMMUNITY LICENCING AND REGULATING OF TRADES, OCCUPATIONS AND BUSI NESSES WHEREAS Council may, pursuant to Section 8(6) of the Community Chorter, regulate in relation to business; AND WHEREAS pursuant to Section 14 of the Community Chorter, two or more municipalities may, by bylawadopted bythe Councilof each participating municipality, establish an inter-municipalscheme in relation to one or more matters; AND WHEREAS pursuant to Section 15(1) of The Community Chorter, Council may provide terms and conditions that may be imposed for obtaining, continuing to hold or renewing a licence, permit or approval and specify the nature of the terms and conditions and who may impose them. NOW THEREFORE the Council of the District of Central Saanich, in open meeting assembled, hereby enacts as follows: L. CITATION This bylaw may be cited as "Central Saanich Inter-Commun¡ty Bus¡ness Licence Bylaw No. 2024 2Ot9." 2. DEFINITIONS ln this bylaw, unless the context otherwise requires, "Business" has the meaning as defined by the "CommLtnity Charter Schedule - Definitions and Rules of lnterpretatio n". "Excluded Business" means a Business excluded from application for an lnter-Community Business Licence and includes those Businesses referred to in Schedule "4" attached hereto and forming part of this bylaw. "lnter-Community Business" means a Business that performs a service or activity within more than one Participating Municipality by moving from client to client rather than having clients come to them. This includes but is not limited to trades, plumbers, electricians, cleaning services, pest control or other similar businesses. -

PORT ALBERNI Have Received World Wide Exploitation

ALBERNI National Ubrary Bibliotheque nationale 1^1 of Canada du Canada Fore\^ord The natural advantages and wonderful prospects of PORT ALBERNI have received world wide exploitation. Unfortu nately, in some few instances, unscrupulous promoters have "manipulated" these facts to sell undesirable property. The Alberni Land Co. Ltd., an English corporation, were the virtual founders, consistent de velopers, and largest handlers of Port Alberni. ' In their behalf we have gath ered the facts for this booklet from the most authentic sources at hand. Representa tions concerning any properties of ours we are prepared to stand behind to the letter, while investigation will prove that our efforts have been consist ently directed to the best inter ests of our clients and the community as well as in our .owown behalfbehalf.. ^ The Alberni Land Co. Ltd. General Ai^ents s General Agents for British Columbia Mainland Carmichael & Moorhead (Limited) Franco-Canadian Victoria, B. C. Port Alberni, B.C. Trust Co. Ltd. Rogers Building Vancouver, B. C. COMPILED BY FOULSER ADVERTISING SERVICE VANCOUVER AND SEATTLE Port Alberni Port Alberni of 1910 TN 1855, Messrs. Anderson, Anderson & Co., shipbrokers, •*- of London, England, heard that there were large areas of splendid timber on the West Coast of Vancouver Island, and in 1860 they sent out Capt. Stamp to investigate the truth of the report. Capt. Stamp chose the head of the Alberni Canal, where Port Alberni now stands, as the most suitable place to erect a sawmill, not only on account of the timber but also because of its suitability as a shipping port to foreign markets. -

Models of Tsunami Waves at the Institute of Ocean Sciences

Models of tsunami waves at the Institute of Ocean Sciences Josef Cherniawsky and Isaac Fine Ocean Science Division, Fisheries & Oceans Canada, Sidney, BC Port Alberni, March 27, 2014 Acknowledgements: Richard Thomson Alexander Rabinovich Kelin Wang Kim Conway Vasily Titov Jing Yang Li Brian Bornhold Maxim Krassovski Fred Stephenson Bill Crawford Pete Wills Denny Sinnott … and others! Our tsunami web site: http://www.pac.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/science/oceans/tsunamis/index-eng.htm … or just search for “DFO tsunami research” An outline … oIntroduction oModels of submarine landslide tsunamis (4 min) oA model of a Cascadia earthquake tsunami (4 min) oTsunami wave amplification in Alberni Inlet (4 min) oA model of the 2012 Haida Gwaii tsunami (4 min) oQuestions Examples of models of landslide generated tsunamis in Canada - some references - Fine, I.V., Rabinovich, A.B., Thomson, R.E. and E.A. Kulikov. 2003. Numerical Modeling of Tsunami Generation by Submarine and Subaerial Landslides. In: Ahmet C. et al. [Eds.]. NATO Science Series, Underwater Ground Failures On Tsunami Generation, Modeling, Risk and Mitigation. Kluwer. 69-88. Fine, I. V., A.B. Rabinovich, B. D. Bornhold, R.E. Thomson and E.A. Kulikov. 2005. The Grand Banks landslide-generated tsunami of November 18, 1929: Preliminary analysis and numerical modeling. Marine Geology. 215: 45-57. Fine, I.V., Rabinovich, A.B., Thomson, R.E., and Kulikov, E.A., 2003. Numerical modeling of tsunami generation by submarine and subaerial landslides, in: Submarine Landslides and Tsunamis, edited by Yalciner, A.C., Pelinovsky, E.N., Synolakis, C.E., and Okal, E., NATO Adv. Series, Kluwer Acad. -

Catalyst Port Alberni Mill

CATALYST PORT ALBERNI MILL Located at the head of picturesque Alberni Inlet on the west coast of Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Catalyst Port Alberni Mill is the single largest employer in the community. Commissioned in 1946, Catalyst Port Alberni Mill was the first British Columbia mill to integrate residuals from sawmills. Committed to environmental sustainability, 95% of Port Alberni’s energy comes from renewable sources with an 88% reduction in greenhouse gases since 1990. ABOUT US The Paper Excellence Catalyst Port Alberni Mill is a leading producer of telephone directory, lightweight coated, and specialty papers for publishers, commercial printers and converters throughout North America, South America and Asia. FACILITIES AND PRODUCTION CAPACITY • West coast’s largest coated paper machine and uncoated groundwood paper machine • State of the art mechanical pulping, utility island and waste water treatment • Directory and coated papers: 336,000 tonnes per year • Coastal BC fibre supply dominated by sawmill residual chips and pulp logs 4000 Stamp Ave, Port Alberni, BC, V9Y 5J7 250.723.2161 / [email protected] / www.paperexcellence.com ECONOMIC CONTRIBUTION • 310 full time employees • 800 indirect jobs in British Columbia SOCIAL ENDEAVORS • $500 million in economic contribution • Robust health and safety program to help protect • Local property taxation of $4.1 million annually employees • Participates in multi-stakeholder development of Somass CARING FOR THE ENVIRONMENT Business Water Management Plan • ISO 14001 environmental -

BC Energy Step Code Builder Guide

BC Energy Step Code Builder Guide October 2018 Version 1.0 | Lower Steps Acknowledgements This guide was funded and commissioned by the Province of BC, BC Housing, BC Hydro, the City of Vancouver, and the City of New Westminster. Acknowledgement is extended to all those who participated in this project as part of the project team or as external reviewers. External Reviewers and Contributors: Architectural Institute of BC FortisBC Maura Gatensby Bea Bains, Dan Bradley BC Housing Glave Communications Bill MacKinnon, Deborah Kraus, James Glave Remi Charron and Wilma Leung Greater Vancouver Homebuilders’ BC Hydro Association Bertine Stelzer, Gary Hamer, Mark Sakai Robyn Wark, Toby Lau HCMA Architecture + Design British Columbia Institute of Technology Johnathon Strebly, Bonnie Retief, Tiffy Riel Alexandre Hebert, Mary McWilliam Integral Group CanmetENERGY, Dave Ramslie, Lisa Westerhoff Natural Resources Canada Alex Ferguson Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing, Building Safety Standards Branch CHBA Zachary May Jack Mantyla Morrison Hershfield CHBA BC Mark Lawton Vanessa Joehl National Research Council of Canada City of New Westminster Mihailo Mihailovic Norm Connolly Travelers City of Vancouver Don Munich Patrick Enright, Chris Higgins Qualico City of Richmond Jonathan Meads Brendan McEwen, Nicholas Heap University of British Columbia Energy Efficiency Branch, Ministry of Ralph Wells Energy and Mines, Province of BC Tom Berkhout Urban Development Institute Jeff Fisher, Clement Chung E3 Eco Group Troy Glasner, Einar Halbig 4 Elements Integrated Design Tyler Hermanson Engineers & Geoscientists BC Harshan Radhakrishnan Produced by: RDH Building Science Inc. James Higgins, Kimberley Wahlstrom, Elyse Henderson, Graham Finch, Torsten Ely ii Builder Guide - BC Energy Step Code © BC Housing About this Guide The Builder Guide to the BC Energy Step Code is published by BC Housing. -

Travel to Port Alberni by Air National Airports – the Closest Airports Are

Travel to Port Alberni By Air National airports – the closest airports are the following: • Comox, BC – WestJet flies to Comox • Nanaimo, BC – Air Canada flies to Nanaimo; WestJet will commence flights to Nanaimo June 2013 Both Air Canada and WestJet offer attractive fare options from across Canada. The above airports are approximately 1 to 1.25 hours by car away from Port Alberni. Local airport – From Vancouver to Qualicum Beach It is possible to fly from the South Terminal of Vancouver Airport via KDAir to Qualicum Beach and they provide a shuttle bus service to Port Alberni: http://www.kdair.com/flights/winter_schedule_eng.html . By Ground BC Ferries – two routes are available from Vancouver to Vancouver Island: • Horseshoe Bay (north of Vancouver) to Departure Bay (downtown Nanaimo) http://www.bcferries.com/schedules/mainland/hbna-current.php • Tsawassen (south of Vancouver Airport) to Duke Point (south of Nanaimo) http://www.bcferries.com/schedules/mainland/tsdp-current.php Driving From Nanaimo : From south of Nanaimo, take Highway #1north in the direction of Campbell River and to avoid driving through downtown Nanaimo, follow the by-pass signs to Campbell River by following Highway 19. Highway 19 takes you north on Vancouver Island, exit at Qualicum Beach and take Highway 4 to Port Alberni. Highway 4 goes to Ucluelet / Tofino / Pacific Rim National Park on the west coast of Vancouver Island. Port Alberni is located in the centre of Vancouver Island – see maps attached. From Comox : Take Highway 19 south in the direction of Nanaimo and exit at Qualicum Beach and take Highway 4 to Port Alberni. -

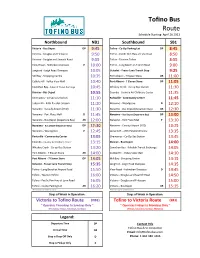

Tofino Bus Route

Tofino Bus Route Schedule Starting: April 26 2021 Northbound NB1 Southbound SB1 Victoria - Bus Depot DP 9:45 Tofino - Co-Op Parking Lot DP 8:45 Victoria - Douglas and Finlayson 9:50 Tofino - Pacific Rim Hwy at Lynn Road 8:50 Victoria - Douglas and Saanich Road 9:55 Tofino - Tourism Tofino 8:55 View Royal - Helmcken Overpass P 10:00 Tofino - Long Beach at Airport Road 9:00 Langford - Leigh Road Overpass 10:05 Ucluelet - Fraser Lane Transit Stop 9:25 Mill Bay - Shopping Centre 10:35 Port Alberni - 7 Eleven Store AR 11:00 Cobble Hill - Valley View Mall 10:40 Port Alberni - 7 Eleven Store DP 11:05 Cowichan Bay - Koksilah Transit Exchange 10:45 Whiskey Creek - Co-op Gas Station 11:30 Duncan - Bus Depot 10:55 Coombs - Country Air Childcare Center 11:35 Chemainus - Co-Op Gas Station 11:10 Parksville - Community Center 11:45 Ladysmith - 49th Parallel Grocery 11:20 Nanaimo - Woodgrove D 12:10 Nanaimo - Cassidy Airport (YCD) 11:30 Nanaimo - Bus Depot (Departure Bay) AR 12:30 Nanaimo - Port Place Mall D 11:45 Nanaimo - Bus Depot (Departure Bay) DP 13:00 Nanaimo - Bus Depot (Departure Bay) AR 12:00 Nanaimo - Port Place Mall P 13:10 Nanaimo - Bus Depot (Departure Bay) DP 12:30 Nanaimo - Cassidy Airport (YCD) 13:25 Nanaimo - Woodgrove P 12:45 Ladysmith - 49th Parallel Grocery 13:35 Parksville - Community Center 13:05 Chemainus - Co-Op Gas Station 13:45 Coombs - Country Air Childcare Center 13:15 Duncan - Bus Depot 14:00 Whiskey Creek - Co-op Gas Station 13:20 Cowichan Bay - Koksilah Transit Exchange 14:05 Port Alberni - 7 Eleven Store AR 14:00 Cobble -

Supreme Court Registry Contact Information

Supreme Court Registries CAMPBELL RIVER 500 - 13th Avenue Campbell River, BC V9W 6P1 Phone Fax Toll-Free Main 250.286.7510 250.286.7512 Scheduling 250.741.5860 250.741.5872 1.877.741.3820 CHILLIWACK 46085 Yale Road Chilliwack, BC V2P 2L8 Phone Fax Main 604.795.8350 Fax Filing 604.795.8397 Civil 604.795.8393 Criminal 604.795.8345 Scheduling 604.795.8349 604.795.8345 COURTENAY Room 100 420 Cumberland Road Courtenay, BC V9N 2C4 Phone Fax Toll-Free Main 250.334.1115 250.334.1191 Scheduling 250.741.5860 250.741.5872 1.877.741.3820 CRANBROOK Room 147 102 - 11th Avenue South Cranbrook, BC V1C 2P3 Phone Fax Main 250.426.1234 250.426.1352 Fax Filing 250.426.1498 Scheduling 250.828.4351 250.828.4332 DAWSON CREEK 1201 - 103rd Avenue Dawson Creek, BC V1G 4J2 Phone Fax Toll-Free Main 250.784.2278 250.784.2339 Fax Filing 250.784.2218 Scheduling 250.614.2750 250.614.2791 1.866.614.2750 DUNCAN 238 Government Street Duncan, BC V9L 1A5 Phone Fax Toll-Free Main 250.746.1227 250.746.1244 1.877.288.0889 Scheduling 250.356.1450 250.952.6824 (not available in the lower mainland) FORT NELSON Bag 1000 4604 Sunset Drive Fort Nelson, BC V0C 1R0 Phone Fax Toll-Free Main 250.774.5999 250.774.6904 Scheduling 250.614.2750 250.614.2791 1.866.614.2750 FORT ST. JOHN 10600 - 100 Street Fort St. John, BC V1J 4L6 Phone Fax Toll-Free Main 250.787.3231 250.787.3518 1.866.614.2750 Scheduling 250.614.2750 250.614.2791 (not available in the lower mainland) GOLDEN 837 Park Drive Golden, BC V0A 1H0 Phone Fax Main 250.344.7581 250.344.7715 KAMLOOPS 223 - 455 Columbia Street Kamloops, -

Community Profile

2019 Community Profile UCLUELET PREPARED BY THE UBERE TEAM UCLUELET CHAMBER OF COMMERCE|1604 Peninsula Road, Ucluelet BC V0R 3A0 Contents Population ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 Population by Age Characteristics ............................................................................................................ 3 Immigration............................................................................................................................................... 5 Language ................................................................................................................................................... 5 Labour Force ................................................................................................................................................. 6 Labour Force by Occupation ..................................................................................................................... 6 Education .................................................................................................................................................. 8 Labour Force Participation Rates .............................................................................................................. 9 Major Employment Sectors ........................................................................................................................ 11 Jobs by Employment .............................................................................................................................. -

Business Case Development

PORT ALBERNI PORT AUTHORITY - CITY OF PORT ALBERNI - CME PORT ALBERNI FLOATING DRYDOCK BUSINESS PLAN CONFIDENTIAL PORT ALBERNI FLOATING DRYDOCK BUSINESS PLAN PORT ALBERNI PORT AUTHORITY - CITY OF PORT ALBERNI - CME PROJECT NO.: 181-12135-01 DATE: DECEMBER 11, 2018 WSP SUITE 1000 840 HOWE STREET VANCOUVER, BC, CANADA V6Z 2M1 T: +1 604 685-9381 F: +1 604 683-8655 WSP.COM TABLE OF EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................ I CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................. 1 2 ASSESSMENT OF CURRENT BC & US PACIFIC NORTHWEST CURRENT & PROPOSED DRYDOCK CAPACITY .............. 2 2.1 British Columbia, Canada Drydocks ........................... 2 2.2 US Drydock Facilities .................................................... 6 3 MARKET DEMAND CONDITIONS ............... 10 4 ASSESSMENT OF SECTORS NOT WELL SERVED ....................................................... 20 5 ASSESSMENT OF SIZE FOR FLOATING DRYDOCK .................................................... 21 6 HIGH LEVEL SWOT ANALYSIS ................... 22 7 ASSESSMENT OF CUSTOMER NEEDS ..... 25 8 EXPANSION TO US PACIFIC NW & ASIA ... 26 9 TRENDS ....................................................... 27 10 EVALUATION OF PROPOSED SITE ........... 28 10.1 Site Description ........................................................... 28 10.2 Site Contamination ...................................................... 30 10.3 Site Development ........................................................ 30 10.4 Suggested Site Layout ............................................... -

REGULAR COUNCIL - 7:00 PM Monday, April 6, 2020 Council Chambers

THE CORPORATION OF THE DISTRICT OF CENTRAL SAANICH REGULAR COUNCIL - 7:00 PM Monday, April 6, 2020 Council Chambers For the time being, all Council meetings are being broadcast live via: http://centralsaanich.ca.granicus.com/ViewPublisher.php?view_id=2 If you wish to submit a comment or question to Council for the meeting, you can email to [email protected] or deliver via the drop box at the front door prior to 12:00 noon on the day of the meeting. Submissions regarding Public Questions will be read aloud at the meeting. Your question(s) may have to be summarized to fit within the allotted time. AGENDA 1. CALL TO ORDER 2. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT We respectfully acknowledge that the land on which we gather is the traditional territory of the W̱ SÁNEĆ people which includes W̱ JOȽEȽP (Tsartlip) and SȾÁUTW̱ (Tsawout) First Nations. 3. APPROVAL OF AGENDA 3.1. Agenda of the April 6, 2020 Regular Council Meeting Recommendation: That the agenda of the April 6, 2020 Regular Council meeting be approved as circulated. 4. ADOPTION OF MINUTES 4.1. Minutes of the March 23, 2020 Regular Council Meeting Pg. 7 - 12 Recommendation: That the minutes of the March 23, 2020 Regular Council meeting be adopted as circulated. 5. BUSINESS ARISING FROM THE MINUTES (including motions and resolutions) 6. RISE AND REPORT No items. 7. PUBLIC QUESTIONS Written submissions will be read aloud. 7.1. Submission from Ryder, N - April 6, 2020 Pg. 13 Re: Parking Bylaw Enforcement 7.2. Submission from Prelusky, April 6, 2020 Pg. 14 Re: Property Tax Payments 8.