Grasshopper Sparrow (Ammodramus Savannarum) Jonathan Mays Description Barrens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grasshopper Sparrow,Ammodramus Savannarum Pratensis

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Grasshopper Sparrow Ammodramus savannarum pratensis pratensis subspecies (Ammodramus savannarum pratensis) in Canada SPECIAL CONCERN 2013 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2013. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Grasshopper Sparrow pratensis subspecies Ammodramus savannarum pratensis in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. ix + 36 pp. (www.registrelep- sararegistry.gc.ca/default_e.cfm). Production note: COSEWIC acknowledges Carl Savignac for writing the status report on the Grasshopper Sparrow pratensis subspecies, Ammodramus savannarum pratensis in Canada, prepared with the financial support of Environment Canada. This report was overseen and edited by Marty Leonard, Co-chair of the COSEWIC Birds Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: 819-953-3215 Fax: 819-994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur le Bruant sauterelle de la sous- espèce de l’Est (Ammodramus savannarum pratensis) au Canada. Cover illustration/photo: Grasshopper Sparrow pratensis subspecies — photo by Jacques Bouvier. Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2014. Catalogue No. CW69-14/681-2014E-PDF ISBN 978-1-100-23548-6 Recycled paper COSEWIC Assessment Summary Assessment Summary – November 2013 Common name Grasshopper Sparrow - pratensis subspecies Scientific name Ammodramus savannarum pratensis Status Special Concern Reason for designation In Canada, this grassland bird is restricted to southern Ontario and southwestern Quebec. -

Using Structured Decision Making to Prioritize Species Assemblages for Conservation T ⁎ Adam W

Journal for Nature Conservation 45 (2018) 48–57 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal for Nature Conservation journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jnc Using Structured Decision Making to prioritize species assemblages for conservation T ⁎ Adam W. Greena, , Maureen D. Corrella, T. Luke Georgea, Ian Davidsonb, Seth Gallagherc, Chris Westc, Annamarie Lopatab, Daniel Caseyd, Kevin Ellisone, David C. Pavlacky Jr.a, Laura Quattrinia, Allison E. Shawa, Erin H. Strassera, Tammy VerCauterena, Arvind O. Panjabia a Bird Conservancy of the Rockies, 230 Cherry St., Suite 150, Fort Collins, CO, 80521, USA b National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, 1133 15th St NW #1100, Washington, DC, 20005, USA c National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, 44 Cook St, Suite 100, Denver, CO, 80206, USA d Northern Great Plains Joint Venture, 3302 4th Ave. N, Billings, MT, 59101, USA e World Wildlife Fund, Northern Great Plains Program, 13 S. Willson Ave., Bozeman, MT, 59715, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Species prioritization efforts are a common strategy implemented to efficiently and effectively apply con- Conservation planning servation efforts and allocate resources to address global declines in biodiversity. These structured processes help Grasslands identify species that best represent the entire species community; however, these methods are often subjective Priority species and focus on a limited number of species characteristics. We developed an objective, transparent approach using Prioritization a Structured Decision Making (SDM) framework to identify a group of grassland bird species on which to focus Structured decision making conservation efforts that considers biological, social, and logistical criteria in the Northern Great Plains of North America. The process quantified these criteria to ensure representation of a variety of species and habitats and included the relative value of each criterion to the working group. -

Species Assessment for Grasshopper Sparrow

Species Status Assessment Class: Birds Family: Emberizidae Scientific Name: Ammodramus savannarum Common Name: Grasshopper sparrow Species synopsis: Four subspecies of grasshopper sparrow occur in North America. This is a sparrow of open grasslands and prairies with habitats containing more shrubs utilized in the southwest (Vickery 1996). As a grassland bird, the grasshopper sparrow is one of the most severely declining species in New York. Breeding Bird Atlas data shows a decline of 42% between the two Atlas periods, 1980-85 to 2000-05. BBS data show significant long-term and short term declines in the state and in the Eastern BBS region. Areas of concentration include the Finger Lakes region, the central portion of the Southern Tier, and Jefferson County. It is sparsely distributed across the Mohawk Valley and persists in the eastern Suffolk County barrens habitat on Long Island (Smith 2008). I. Status a. Current Legal Protected Status i. Federal _____Not Listed________________________ Candidate: __No__ ii. New York _____Special Concern; SGCN__________________________________ b. Natural Heritage Program Rank i. Global _____G5________________________________________________________ ii. New York _____S3_______________________ Tracked by NYNHP? _No__ Other Rank: New York Natural Heritage Program Watch List Partners in Flight: Species of Continental Importance 1 Status Discussion: The grasshopper sparrow is a fairly common but local breeder on eastern Long Island and in interior lowlands of the Appalachian Plateau and the Great Lakes Plain. It is absent from Alleghenies, Adirondacks, Catskills. Declines noted between the first and second Breeding Bird Atlas projects have occurred in all regions of occurrence within the state. Grasshopper sparrow is ranked as Vulnerable, Imperiled, or Critically Imperiled in all northeastern states and provinces except in Pennsylvania and Ontario, where it is considered Apparently Secure. -

Grasshopper Sparrow (Ammodramus Savannarum Ammolegus) “Arizona

Grasshopper Sparrow (Ammodramus savannarum ammolegus) “Arizona Grasshopper Sparrow” NMPIF level: Species Conservation Concern, Level 1 (SC1) NMPIF assessment score: 20 NM stewardship responsibility: High New Mexico BCRs: 34 Primary breeding habitat(s): Chihuahuan Desert Grasslands (Ammodramus savannarum perpallidus) NMPIF level: Biodiversity Conservation Concern, Level 2 (BC2) NMPIF assessment score: 12 NM stewardship responsibility: Low National PIF status: Stewardship. New Mexico BCRs: 16, 18, 34, 35 (most in 18) Primary breeding habitat(s): Plains-Mesa Grasslands Other habitats used: Chihuahuan Desert Grasslands, Agricultural Summary of Concern Grasshopper Sparrow is a grassland species that has undergone large, long-term population declines in many areas. A . s. ammolegus is a subspecies restricted to a small area of the southwest United States and northern Mexico; the small New Mexico population has been declining. Other subspecies are locally present in suitable grassland areas in the east. These populations should be monitored for further declines. Associated Species Northern Harrier, Eastern Meadowlark Distribution One of twelve Grasshopper Sparrow subspecies, and one of four breeding in the United States, A. s. ammolegus breeds only in a very small area, including parts of southeast Arizona, southwest New Mexico, and north Sonora. The winter range of this taxon is poorly known; some A. s. ammolegus remain in the United States, others migrate to central Mexico and possibly south into Central America. In New Mexico, A. s. ammolegus is found only in the Animas and Playas valleys, in Hidalgo County (Phillips et al. 1978, Vickery 1996). A. s. perpallidus is broadly distributed across the west and Great Plains, from southern Canada to the Mexican border states. -

Grasshopper Sparrow Minnesota Conservation Plan

Jim Williams Jim Credit: Grasshopper Sparrow Minnesota Conservation Plan Audubon Minnesota Spring 2014 The Blueprint for Minnesota Bird Conservation is a project of Audubon Minnesota written by Lee A. Pfannmuller ([email protected]) and funded by the Environment and Natural Resources Trust Fund. For further information please contact Mark Martell at [email protected] (651-739-9332). Table of Contents Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................... 5 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 6 Background ................................................................................................................................................... 6 Status ......................................................................................................................................................... 6 Legal Status ........................................................................................................................................... 6 Other Status Classifications .................................................................................................................. 6 Range ........................................................................................................................................................ 7 Historical Breeding Range ................................................................................................................... -

1 Testimony of Dr. Reed F. Noss to House Committee on Natural

Testimony of Dr. Reed F. Noss to House Committee on Natural Resources Oversight Hearing on “Defining Species Conservation Success: Tribal, State and Local Stewardship vs. Federal Courtroom Battles and Sue‐and‐ Settle Practices,” Tuesday, June 4, 2013. Good morning, Chairman Hastings, Representative Bordallo, and the other members of the Committee on Natural Resources. My name is Dr. Reed Noss. I am the Provost’s Distinguished Research Professor of Biology at the University of Central Florida. I have served as President of the Society for Conservation Biology and Editor‐in‐ Chief of its scientific journal, Conservation Biology. I am an Elected Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. I have worked in the fields of ecology and conservation biology for four decades, coinciding precisely with the venerable history of the U.S. Endangered Species Act of 1973. I teach conservation biology, ecosystems of Florida, ornithology, and history of ecology. My current research centers on the vulnerability of species and ecosystems to land‐use change, climate change, and sea‐level rise, and what we might do to address those threats. I have nearly 300 publications, including seven books, and am rated as one of the 500 most highly cited authors in all fields. I am honored to address this committee during the 40th anniversary year of the U.S. Endangered Species Act, passed by Congress with nearly unanimous support and signed by President Richard Nixon in 1973. This Act is nothing less than one the most important and influential pieces of conservation legislation in the history of the world. -

Pennsylvania Game Commission Cooperative Agreement ME231002

Effects of Local and Landscape Features on Avian Use and Productivity on Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program Fieldsa Kevin Wentworth, Pennsylvania State University, School of Forest Resources, 320 Forest Resources Lab, University Park, Pennsylvania, 16802; and Dr. Margaret Brittingham, Pennsylvania State University, School of Forest Resources, 320 Forest Resources Lab, University Park, Pennsylvania, 16802. Abstract: In 2001, a federal program, the Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program (CREP), was initiated in 20 counties in south-central Pennsylvania to address soil erosion problems and to provide habitat for wildlife. We examined avian use and productivity of CREP fields and how this compared with hayfields. We wanted to identify what field and landscape characteristics affected use and productivity of CREP fields. We randomly selected CREP fields in three size categories: 2.0 – 4.0 ha, 7.3 – 12 ha, and 16 – 28 ha. Hayfields were located as near as possible to selected CREP fields. We surveyed birds in all fields, using distance sampling, and nest searched half the fields. We made a total 1,929 observations of 31 different species on 114 CREP fields and 68 observations of 7 different species on 16 hayfields. From 2001 - 2004, we monitored 969 nests of 19 species in 73 CREP fields and 87 nests of 5 species on 15 hayfields. We found both landscape and field characteristics affected nest abundance and bird density on CREP fields, using Poisson regressions. The most common species were red-winged blackbirds (Agelaius phoeniceus), field sparrows (Spiza pusilla) and song sparrows (Melospiza melodia). The most common grassland specialists were grasshopper sparrows (Ammodramus savannarum) and eastern meadowlarks (Sturnella magna) though they were both uncommon. -

Florida Grasshopper Sparrow (Ammodramus Savannarum Floridanus) Conspecific Attraction Experiment

FLORIDA GRASSHOPPER SPARROW (AMMODRAMUS SAVANNARUM FLORIDANUS) CONSPECIFIC ATTRACTION EXPERIMENT THOMAS VIRZI ECOSTUDIES INSTITUTE P.O. BOX 735 EAST OLYMPIA, WA 98540 [email protected] REPORT TO THE U.S. FISH & WILDLIFE SERVICE (SOUTH FLORIDA ECOLOGICAL SERVICES, VERO BEACH, FL) AND THE FISH & WILDLIFE FOUNDATION OF FLORIDA (TALLAHASSEE, FL) DECEMBER 2015 Contents 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................................................. 3 2.0 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................................... 7 2.1 PURPOSE ......................................................................................................................................................... 7 2.2 FIGURES ........................................................................................................................................................ 11 3.0 PLAYBACK EXPERIMENT .......................................................................................................................... 13 3.1 BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................................ 13 3.2 METHODS ..................................................................................................................................................... 13 3.3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION ............................................................................................................................... -

Status Assessment Includes Summaries of the Status of Henslow's Sparrow in 38 States and Canada, Which Make up the Current and Historic Range of the Species

ii TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY........................................................ 1 TAXONOMY....................................................... 3 PHYSICAL DESCRIPTION, SONG, AND GENERAL BEHAVIOR............... 3 RANGE.......................................................... 4 HABITAT........................................................ 6 BREEDING SEASON HABITAT REQUIREMENTS ......................... 6 WINTER HABITAT REQUIREMENTS .................................. 9 BIOLOGY....................................................... 11 MIGRATION ................................................... 11 REPRODUCTION ................................................ 12 FOOD HABITS ................................................. 14 POPULATION TRENDS AND ESTIMATES............................... 15 NORTH AMERICAN BREEDING BIRD SURVEY ......................... 15 BREEDING BIRD ATLASES ....................................... 17 CHRISTMAS BIRD COUNTS ....................................... 17 STATE SUMMARIES ............................................. 18 FWS REGION 2 .............................................. 19 Oklahoma................................................. 19 Texas.................................................... 21 FWS REGION 3 .............................................. 22 Illinois................................................. 22 Indiana.................................................. 24 Iowa..................................................... 25 Michigan................................................. 26 -

Grasshopper Sparrow Ammodramus Savannarum

Appendix A: Birds Grasshopper Sparrow Ammodramus savannarum Federal Listing N/A State Listing T Global Rank G5 State Rank S2 Regional Status Very High Photo by Len Medlock Justification (Reason for Concern in NH) Populations of most grassland birds are in strong decline, both in the Northeast and sometimes across larger portions of their continental ranges. For this reason, most species were included in the Northeast list of SGCN, with those that occur regularly in NH retained for the NH WAP revision. Based on BBS data (Sauer et al. 2014), Grasshopper Sparrow populations in the Northeast have declined at 4.26% annually since 1966 (‐3.4%/year from 2003‐2013). Because of the species’ overall rarity, BBS data on smaller scales (e.g., NH) are less accurate, although the species also shows a significant annual decline of 3.64% in BCR 30. There have also been declines of 15‐75% based on repeated Breeding Bird Atlases in the northeast (Cadman et al. 2007, McGowan and Corwin 2008, Renfrew 2013, MassAudubon 2014). Grasshopper Sparrows were never common in New Hampshire, but have declined since the 1960s and are now found primarily at 5‐6 sites in the southern part of the state. Distribution Grasshopper Sparrows breed across the United States and extreme southern Canada, although this distribution is more disjunct west of the Great Plains (Vickery 1996). Most of this population winters in Mexico and the southeastern United States. There are also isolated resident populations in Central America, the Greater Antilles, and extreme northwestern South America. In New Hampshire, the species has historically occurred south of the White Mountains, with most records in the Connecticut and Merrimack Valleys and near the seacoast (Foss 1994). -

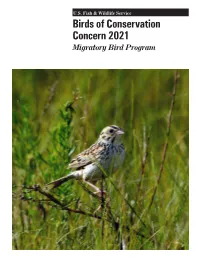

Birds of Conservation Concern 2021 Migratory Bird Program Table of Contents

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Birds of Conservation Concern 2021 Migratory Bird Program Table Of Contents Executive Summary 4 Acknowledgments 5 Introduction 6 Methods 7 Geographic Scope 7 Birds Considered 7 Assessing Conservation Status 7 Identifying Birds of Conservation Concern 10 Results and Discussion 11 Literature Cited 13 Figures 15 Figure 1. Map of terrestrial Bird Conservation Regions (BCRs) Marine Bird Conservation Regions (MBCRs) of North America (Bird Studies Canada and NABCI 2014). See Table 2 for BCR and MBCR names. 15 Tables 16 Table 1. Island states, commonwealths, territories and other affiliations of the United States (USA), including the USA territorial sea, contiguous zone and exclusive economic zone considered in the development of the Birds of Conservation Concern 2021. 16 Table 2. Terrestrial Bird Conservation Regions (BCR) and Marine Bird Conservation Regions (MBCR) either wholly or partially within the jurisdiction of the Continental USA, including Alaska, used in the Birds of Conservation Concern 2021. 17 Table 3. Birds of Conservation Concern 2021 in the Continental USA (CON), continental Bird Conservation Regions (BCR), Puerto Rico and Virgin Islands (PRVI), and Hawaii and Pacific Islands (HAPI). Refer to Appendix 1 for scientific names of species, subspecies and populations Breeding (X) and nonbreeding (nb) status are indicated for each geography. Parenthesized names indicate conservation concern only exists for a specific subspecies or population. 18 Table 4. Numbers of taxa of Birds of Conservation Concern 2021 represented on the Continental USA (CON), continental Bird Conservation Region (BCR), Puerto Rico and VirginIslands (PRVI), Hawaii and Pacific Islands (HAPI) lists by general taxonomic groups. Also presented are the unique taxa represented on all lists. -

Sharp-Tailed Grouse

NORTHERN GREAT PLAINS JOINT VENTURE PRIORITY BIRD SPECIES August 2012 By: Northern Great Plains Joint Venture Technical Committee 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction...............................................................3 Methods.....................................................................3 Results.......................................................................7 Baird’s Sparrow...........................................11 Black-billed Cuckoo....................................14 Black-billed Magpie.....................................17 Brewer’s Sparrow........................................20 Burrowing Owl............................................23 Chestnut-collared Longspur........................26 Ferruginous Hawk.......................................29 Grasshopper Sparrow..................................32 Greater Sage-grouse....................................35 Lark Bunting...............................................38 Loggerhead Shrike.......................................41 Long-billed Curlew.....................................44 Mallard.........................................................47 Marbled Godwit..........................................50 McCown’s Longspur...................................53 Mountain Plover..........................................56 Northern Pintail...........................................59 Red-headed Woodpecker............................62 Sharp-tailed Grouse.....................................65 Short-eared Owl..........................................68