Static Allometry Suggests Female Ornaments in the Long-Tailed Dance Y

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Frontenac Provincial Park

FRONTENAC PROVINCIAL PARK One Malaise trap was deployed at Frontenac Provincial Park in 2014 (44.51783, -76.53944, 176m ASL; Figure 1). This trap collected arthropods for twenty weeks from May 9 – September 25, 2014. All 10 Malaise trap samples were processed; every other sample was analyzed using the individual specimen protocol while the second half was analyzed via bulk analysis. A total of 3372 BINs were obtained. Half of the BINs captured were flies (Diptera), followed by bees, ants and wasps (Hymenoptera), moths and butterflies (Lepidoptera), and true bugs (Hemiptera; Figure 2). In total, 750 arthropod species were named, representing 24.6% of the BINs from the site (Appendix 1). All but 1 of the BINs were assigned Figure 1. Malaise trap deployed at Frontenac at least to family, and 58.2% were assigned to a genus Provincial Park in 2014. (Appendix 2). Specimens collected from Frontenac represent 232 different families and 838 genera. Diptera Hymenoptera Lepidoptera Hemiptera Coleoptera Trombidiformes Psocodea Trichoptera Araneae Mesostigmata Entomobryomorpha Thysanoptera Neuroptera Orthoptera Sarcoptiformes Blattodea Mecoptera Odonata Symphypleona Ephemeroptera Julida Opiliones Figure 2. Taxonomy breakdown of BINs captured in the Malaise trap at Frontenac. APPENDIX 1. TAXONOMY REPORT Class Order Family Genus Species Arachnida Araneae Clubionidae Clubiona Clubiona obesa Dictynidae Emblyna Emblyna annulipes Emblyna sublata Gnaphosidae Cesonia Cesonia bilineata Linyphiidae Ceraticelus Ceraticelus fissiceps Pityohyphantes Pityohyphantes -

Sexual Selection and Female Ornamentation in a Role- Reversed Dance Fly

SEXUAL SELECTION AND FEMALE ORNAMENTATION IN A ROLE- REVERSED DANCE FLY By Jill Wheeler A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of MSc Graduate Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology University of Toronto © Copyright by Jill Wheeler (2008) Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-45023-9 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-45023-9 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Diptera, Empidoidea) Du Rif Méditerranéen (Maroc) Preliminary Generic Inventory of Empididae (Diptera, Empidoidea) from the Mediterranean Rif (Morocco)

Travaux de l’Institut Scientifique, Rabat, Série Zoologie, 2013, n°49, 59-69. Données génériques préliminaires sur les Empididae (Diptera, Empidoidea) du Rif méditerranéen (Maroc) Preliminary generic inventory of Empididae (Diptera, Empidoidea) from the Mediterranean Rif (Morocco) Fatima Zohra BAHID* & Kawtar KETTANI Université Abd El Malek Essaadi, Faculté des Sciences, Laboratoire Diversité et Conservation des Systèmes Biologiques, Mhannech II, B.P.: 2121, Tétouan, Maroc *([email protected];[email protected]) Résumé. Un inventaire générique préliminaire des Empididae est établi à partir d’un matériel collecté dans le Rif Méditerranéen, au Nord du Maroc. Treize genres ont pu être identifiés, dont 11 se révèlent nouveaux pour le Rif dont 7 pour le Maroc. Le nombre de genres d’Empididae actuellement connu à l’échelle du pays s’élève à 13. Mots-clés : Diptera, Empididae, biogéographie, Rif, Maroc. Abstract. A Preliminery generic list of Empididae is given based on materiel collected in the Rif (Northern Morocco). Among the thirteen reported, 11 are new for the Rif and 7 for Morocco. This inventory increases to 13 the total number of genus found until now in Morocco. Keywords : Diptera, Empididae, faunistic, biogeography, Rif, Morocco. Abridged English version A total of 239 individuals were captured after multiple A Preliminery generic list of Empididae is given based surveys in various habitats. The list of Empididae includes on materiel collected in the Rif of Northern Morocco. 13 13 genera belonging to 5 subfamilies: Hemerodrominae (3 genera have been identified, 11 are new records for the Rif genera), Clinocerinae (3 genera), Empidinae (3 genera), and 7 for Morocco. -

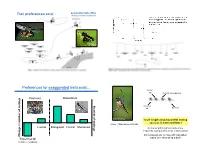

Preferences for Exaggerated Traits Exist… Control I ! Control II (Unmanipulated)

Long-tailed dance flies Long-tailed dance fly – Rhamphomyia longicauda Trait preferences exist… Rhamphomyia longicauda Preferences for exaggerated traits exist… Control I ! Control II (unmanipulated) Peacocks Widowbirds Number of matings Shortened ! Elongated barn swallow Is tail length associated with mating success in barn swallows? Moller (1988) Nature 332:640 Control Elongated Control Shortened Do males with long tails mate more frequently (compared to short-tailed males)? Do females prefer to mate with long tailed Change in number of matings Experimental males over short-tailed males? (remove eyesptos) ! ! ! ! barn swallow barn swallow Moller (1988) Nature 332:640 Moller (1988) Nature 332:640 Males with elongated tails found Males with elongated tails mates more quickly re-mated more frequently …but what is it that males (or females) choosing? Hypotheses for how mate choice evolves... ! ! • Honest advertisement • Individuals increase their fitness by selecting mates whose characteristics indicate that they are of high quality. • Direct benefits to individuals of the choosy sex • Indirect benefits (e.g., good genes for offspring of choosy sex) barn swallow Females paired with short-tailed males more likely to accept extra matings Males with elongated tails had more offspring long-tailed males were Extra pair copulations more successful at By males gaining extra matings By their female pair- mates Indirect benefits: Good genes hypothesis Direct benefits: food In nature… Bittacus apicalis Exaggerated traits indicate the genetic quality -

Salutations, Bugfans, the Stars of Today's Show Is the Dance Fly, A

Salutations, BugFans, The stars of today’s show is the Dance fly, a member of the Order Diptera (“two-wings”). Flies come in an amazing variety of species (some 17,000 different kinds grace North America), and sizes (from barely visible to crane- fly-size), and shapes (long and leggy to short and chunky). Despite all that variety, these carnivores/herbivores/scavengers have been issued only two types of mouthparts - piercing-sucking (think deer fly) or sponging (think horse fly). Dance flies, in the family Empididae, get their name from the habit of males of some species to gather in large groups and dance up and down in the air in the hopes of attracting females. They can also be found hunting for small insects on and under vegetation in shady areas and on front porches at night (dance flies are very effective mosquito-predators, but both genders may also eat nectar). The BugLady thinks these may be Long-tailed Dance flies (Rhamphomyia longicauda). The males’ red eyes cover their heads like helmets, and their reproductive organs, located at the tip of their abdomen, are often conspicuous (which sharp-eyed BugFans can just see on the Dance Fly that’s reading the newspaper). The red eyes of the females do not meet in the middle, and she has feathery fringes on her legs. Like the (unrelated) Scorpionflies of previous BOTW fame, male dance flies give their sweeties a nuptial gift to eat while they mate; in fact, females of some species, like the Long-tailed Dance Fly, depend completely on their suitors for food. -

Contrasting Sexual Selection on Males and Females in a Rolereversed

Contrasting sexual selection on males and females in a rolereversed swarming dancefly, Rhamphomyia longicauda Loew (Diptera: Empididae). Luc F. Bussière1,2,3, Darryl T. Gwynne1, and Rob Brooks2 1. Biology Group, University of Toronto at Mississauga Mississauga, Ontario, L5L 1C6, Canada 2. Evolution & Ecology Research Centre and School of Biological, Earth, and Environmental Sciences, University of New South Wales, Sydney, New South Wales, 2052, Australia 3. Corresponding author’s current address: School of Biological and Environmental Sciences, University of Stirling, FK9 4LA, Stirling, United Kingdom Email: [email protected] Abstract Sex-specific ornamentation is widely known among male animals, but even among sex-role reversed species, ornamented females are rare. Although several hypotheses for this pattern exist, too few systems featuring female ornaments have been studied in detail to adequately test them. Empidine dance flies are exceptional in that many species show female ornamentation of wings, abdomens, or legs. Here we compare sexual selection in males and females of the long-tailed dance fly, Rhamphomyia longicauda Loew (Diptera: Empididae), a sex-role reversed fly in which swarming females aggregate in competition for the nuptial gifts provided by males during mating. Females in this species possess several secondary sex characters, including eversible abdominal sacs, enlarged wings, and decorated tibiae that may all function in mate attraction during swarming. Males preferentially approach large females in the swarm, but the strength and shape of selection on females and the degree to which selection is sex-specific are unknown. We estimated linear and nonlinear sexual selection on structures expressed in both male and female flies, and found contrasting patterns of sexual selection on wing length and tibia length in males and females. -

Appendix 5: Fauna Known to Occur on Fort Drum

Appendix 5: Fauna Known to Occur on Fort Drum LIST OF FAUNA KNOWN TO OCCUR ON FORT DRUM as of January 2017. Federally listed species are noted with FT (Federal Threatened) and FE (Federal Endangered); state listed species are noted with SSC (Species of Special Concern), ST (State Threatened, and SE (State Endangered); introduced species are noted with I (Introduced). INSECT SPECIES Except where otherwise noted all insect and invertebrate taxonomy based on (1) Arnett, R.H. 2000. American Insects: A Handbook of the Insects of North America North of Mexico, 2nd edition, CRC Press, 1024 pp; (2) Marshall, S.A. 2013. Insects: Their Natural History and Diversity, Firefly Books, Buffalo, NY, 732 pp.; (3) Bugguide.net, 2003-2017, http://www.bugguide.net/node/view/15740, Iowa State University. ORDER EPHEMEROPTERA--Mayflies Taxonomy based on (1) Peckarsky, B.L., P.R. Fraissinet, M.A. Penton, and D.J. Conklin Jr. 1990. Freshwater Macroinvertebrates of Northeastern North America. Cornell University Press. 456 pp; (2) Merritt, R.W., K.W. Cummins, and M.B. Berg 2008. An Introduction to the Aquatic Insects of North America, 4th Edition. Kendall Hunt Publishing. 1158 pp. FAMILY LEPTOPHLEBIIDAE—Pronggillled Mayflies FAMILY BAETIDAE—Small Minnow Mayflies Habrophleboides sp. Acentrella sp. Habrophlebia sp. Acerpenna sp. Leptophlebia sp. Baetis sp. Paraleptophlebia sp. Callibaetis sp. Centroptilum sp. FAMILY CAENIDAE—Small Squaregilled Mayflies Diphetor sp. Brachycercus sp. Heterocloeon sp. Caenis sp. Paracloeodes sp. Plauditus sp. FAMILY EPHEMERELLIDAE—Spiny Crawler Procloeon sp. Mayflies Pseudocentroptiloides sp. Caurinella sp. Pseudocloeon sp. Drunela sp. Ephemerella sp. FAMILY METRETOPODIDAE—Cleftfooted Minnow Eurylophella sp. Mayflies Serratella sp. -

Opportunity for Male Mate Choice? Male Reproductive Costs in Sabethes Cyaneus- a Mosquito with Elaborate Ornaments Expressed by Both Sexes

Opportunity for male mate choice? Male reproductive costs in Sabethes cyaneus- a mosquito with elaborate ornaments expressed by both sexes Dianna Steiner Master of Science Thesis in Evolutionary Biology 2007-2008 Supervisors: Göran Arnqvist, Sandra South Uppsala University, Norbyvägen 18D, 752 36 Uppsala, Sweden 1 ABSTRACT Mutual ornamentation may evolve through male and female adaptive mate choice, natural selection for the same trait in both sexes, or be a non-adaptive result of an intersexual genetic correlation. Both males and females of the mosquito Sabethes cyaneus express elaborate ornaments. S. cyaneus behavior and characteristics of the ornament suggest that the latter two explanations for mutual ornamentation are improbable in this case; however, adaptive choice seems plausible. This study investigated the opportunity for male mate choice in S. cyaneus by experimentally examining male reproductive costs. Costs were deduced by comparing the longevity of three treatment groups: (i) males allowed to engage in courtship and copulation, (ii) males allowed to court but deprived of copulation, and (iii) males deprived of both courtship and copulation. Although males suffered costs due to sexual activity, the observed decrease in lifespan was statistically non-significant. Courtship activity was negatively correlated to lifespan and although males allowed to copulate suffered the highest mortality, copulations were found to be positively correlated to lifespan. This data, combined with a low observed mating rate, suggest that copulation success could be condition-dependent. Despite the non-significant lifespan difference among male treatment groups, I believe that male reproductive costs of S. cyaneus may be of biological importance and I discuss potential influencing factors. -

Zootaxa, Empidoidea (Diptera)

ZOOTAXA 1180 The morphology, higher-level phylogeny and classification of the Empidoidea (Diptera) BRADLEY J. SINCLAIR & JEFFREY M. CUMMING Magnolia Press Auckland, New Zealand BRADLEY J. SINCLAIR & JEFFREY M. CUMMING The morphology, higher-level phylogeny and classification of the Empidoidea (Diptera) (Zootaxa 1180) 172 pp.; 30 cm. 21 Apr. 2006 ISBN 1-877407-79-8 (paperback) ISBN 1-877407-80-1 (Online edition) FIRST PUBLISHED IN 2006 BY Magnolia Press P.O. Box 41383 Auckland 1030 New Zealand e-mail: [email protected] http://www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ © 2006 Magnolia Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, transmitted or disseminated, in any form, or by any means, without prior written permission from the publisher, to whom all requests to reproduce copyright material should be directed in writing. This authorization does not extend to any other kind of copying, by any means, in any form, and for any purpose other than private research use. ISSN 1175-5326 (Print edition) ISSN 1175-5334 (Online edition) Zootaxa 1180: 1–172 (2006) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ ZOOTAXA 1180 Copyright © 2006 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) The morphology, higher-level phylogeny and classification of the Empidoidea (Diptera) BRADLEY J. SINCLAIR1 & JEFFREY M. CUMMING2 1 Zoologisches Forschungsmuseum Alexander Koenig, Adenauerallee 160, 53113 Bonn, Germany. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Invertebrate Biodiversity, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, C.E.F., Ottawa, ON, Canada -

The Evolution of Extended Sexual Receptivity in Chimpanzees: Variation, Male-Female Associations, and Hormonal Correlates

The Evolution of Extended Sexual Receptivity in Chimpanzees: Variation, Male-Female Associations, and Hormonal Correlates by Emily Elizabeth Blankinship Boehm Department of Evolutionary Anthropology Duke University Date:____________________ Approved: ___________________________ Anne E. Pusey, Supervisor ___________________________ Susan Alberts ___________________________ Christine Drea ___________________________ Stephen Nowicki ___________________________ Charles Nunn ___________________________ Christine Wall Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Evolutionary Anthropology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2016 ABSTRACT The Evolution of Extended Sexual Receptivity in Chimpanzees: Variation, Male-Female Associations, and Hormonal Correlates by Emily Elizabeth Blankinship Boehm Department of Evolutionary Anthropology Duke University Date:____________________ Approved: ___________________________ Anne Pusey, Supervisor ___________________________ Susan Alberts ___________________________ Christine Drea ___________________________ Stephen Nowicki ___________________________ Charles Nunn ___________________________ Christine Wall An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Evolutionary Anthropology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2016 Copyright by Emily Elizabeth Blankinship Boehm 2016 Abstract Sexual conflict occurs when female and male -

ABSTRACT TURNER, STEVEN PAUL. the Evolution of Sexually Selected

ABSTRACT TURNER, STEVEN PAUL. The Evolution of Sexually Selected Traits in Dance Flies. (Under the direction of Dr. Brian Wiegmann.) The Diptera family Empididae is a successful and species rich radiation of the superfamily Empidoidea. Flies in this family are well documented to engage in a myriad of elaborate courtship displays, which has made them model organisms of choice for behavioral and evolutionary biologists studying the evolution of sexual selection. Chapter 1 of this thesis aims to summarize the variation of courtship strategies of flies in the empidid subfamily, Empidinae. I focus on nuptial gift presentation and variation in types of nuptial gifts. I also briefly discuss the occurrences of sex role reversed mating systems and the reasons why these may have evolved. The evolution of potential exploitation of female sensory biases by males in systems where males “cheat” concludes the first chapter. Chapter 2 focuses on how sexual selection drives rapid radiations in nuptial gift giving flies. The focus for this study is Enoplempis a sub genus of Empis. Representatives of this clade have been observed to engage in almost all nuptial gift giving interactions seen across the entire subfamily Empidinae. These range from males presenting unwrapped nuptial prey to females, males constructing “balloons” in which to wrap the prey before presenting it to the female, the production of empty balloons by the males for courtship interactions and sex role reversed systems where males choose swarming females, the converse is normally the case. The study involved behavioral observations, the coding of morphological traits and the use of molecular phylogenies to reconstruct the evolution of courtship traits across Enoplempis. -

Rosalind L. Murray

The ecology and evolution of female-specific ornamentation in the dance flies (Diptera: Empidinae) Rosalind L. Murray Doctor of Philosophy, 2015 Biological & Environmental Sciences University of Stirling © Copyright by Rosalind L. Murray 2015 The ecology and evolution of female-specific ornamentation in the dance flies (Diptera: Empidinae) Rosalind L. Murray Abstract Elaborate morphological ornaments can evolve if they increase the reproductive success of the bearer during competition for mates. However, ornament evolution is incredibly rare in females, and the type and intensity of selection required to develop female-specific ornamentation is poorly understood. The main goals of my thesis are to clarify the relationship between the type and intensity of sexual selection that drives the evolution of female ornamentation, and investigate alternative hypotheses that might be limiting or contributing to the development of female ornaments. I investigated the ecology and evolution of female-specific ornaments within and between species of dance flies from the subfamily Empidinae (Diptera: Empididae). The dance flies display incredible mating system diversity including those with elaborate female-specific ornaments, lek-like mating swarms, aerial copulation and nuptial gift giving. To elucidate the form of sexual selection involved in female-ornament evolution, I experimentally investigated the role of sexual conflict in the evolution of multiple female- specific ornaments in the species Rhamphomyia longicauda. Through manipulative field experiments, I found that variation in the attractiveness of two ornaments displayed by females indicates that sexual conflict, causing a coevolutionary arms race, is an important ii force in the evolution of multiple extravagant female ornaments. Using R. longicauda again, I tested for a role of functional load-lifting constraints on the aerial mating ability of males who paired with females displaying multiple large ornaments.