Old England, Nostalgia, and the "Warwickshire" of Shakespeare's Mind

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Dull Soldier and a Keen Guest: Stumbling Through the Falstaffiad One Drink at a Time

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2017 A Dull Soldier and a Keen Guest: Stumbling Through The Falstaffiad One Drink at a Time Emma Givens Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Dramatic Literature, Criticism and Theory Commons, and the Theatre History Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/4826 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Emma Givens 2017 All rights reserved A Dull Soldier and a Keen Guest: Stumbling Through The Falstaffiad One Drink at a Time A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts at Virginia Commonwealth University. Emma Pedersen Givens Director: Noreen C. Barnes, Ph.D. Director of Graduate Studies Department of Theatre Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia March, 2017 ii Acknowledgement Theatre is a collaborative art, and so, apparently, is thesis writing. First and foremost, I would like to thank my grandmother, Carol Pedersen, or as I like to call her, the world’s greatest research assistant. Without her vast knowledge of everything Shakespeare, I would have floundered much longer. Thank you to my mother and grad-school classmate, Boomie Pedersen, for her unending support, my friend, Casey Polczynski, for being a great cheerleader, my roommate, Amanda Long for not saying anything about all the books littered about our house and my partner in theatre for listening to me talk nonstop about Shakespeare over fishboards. -

UNPACKING the MERRY WIVES Robert Brazil K

UNPACKING THE MERRY WIVES Robert Brazil k HAKESPEARE’S play, The Merry Wives of Windsor, is filled with fascinating enig- mas. This comedy, set in the environs of Windsor Castle, weaves together a street level story of love, lust, greed, competition and humiliation with a commentary on society that, while it spoke directly to the concerns of its contemporary late six- teenth-century audience, abounds with references that are extremely suggestive today to students and researchers of the Oxfordian theory. Because Merry Wives was first printed in 1602, most standard commentators on Shakespeare consider it to be a mid- career play, written while the author was at the height of his powers, roughly simultaneous with Hamlet. Yet everything about the play, including the sensibility, the crude style, and the too-old contemporary allusions, suggests that it was an earlier work, its topical references and concerns those of the 1580s, with some 1590s references added to a later revival, to become an interesting anachronistic revival by 1602. The central ideas and plot elements in Merry Wives involve the high stakes wooing of young Anne Page by three suitors, the farcical woo- ing of Mrs. Ford by three other suitors, the complex humiliations of Falstaff, Master Ford, Slender, Doctor Caius and others, and Master Ford’s fear that he will be cuckolded. As the play begins, Shallow, Slender and Hugh Evans are walking into the village in front of Page’s house. Shallow states that he won’t change his mind, he is going to make a Star Chamber affair out of Falstaff’s offense, introducing a subplot that has little apparent rele- vance to the main plot, but which is filled with accurate descriptions of county lawsuits and disputes and the archaic Latin-based bureaucracy associated with the process. -

The Life of King Henry the Fifth Study Guide

The Life of King Henry the The Dukes of Gloucester and Fifth Bedford: The Study Guide King’s brothers. Compiled by Laura Cole, Duke of Exeter: Director of Education and Training Uncle to the [email protected] King. for The Atlanta Shakespeare Company Duke of York: at The New American Shakespeare Cousin to the King. Tavern Earl’s of Salisbury, Westmoreland and 499 Peachtree Street, NE Warwick: Advisors to the King. Atlanta, GA 30308 Phone: 404-874-5299 The Archbishop of Canterbury and the Bishop of Ely: They know the Salic Law very well! www.shakespearetavern.com The Earl of Cambridge, Sir Thomas Grey and Lord Scroop: English traitors, they take gold Original Practice and Playing from France to kill the King, but are discovered. Scroop is a childhood friend of Henry’s. Shakespeare Gower, Fluellen, Macmorris and Jamy: Captains in the King’s army, English, Welsh, The Shakespeare Tavern on Peachtree Street Irish and Scottish. is an Original Practice Playhouse. Original Practice is the active exploration and Bates, Court, Williams: Soldiers in the King’s implementation of Elizabethan stagecraft army. and acting techniques. Nym, Pistol, Bardolph: English soldiers and friends of the now-dead Falstaff, as well as For the Atlanta Shakespeare Company drinking companions of Henry, when he was (ASC) at The New American Shakespeare Prince Hal. A boy also accompanies the men. Tavern, this means every ASC production features hand-made period costumes, live Hostess of the Boar’s Head Tavern: Nee’ actor-generated sound effects, and live Quickly, now married to Pistol. period music performed on period Charles IV of France: The King of France. -

Merry Wives (Edited 2019)

!1 The Marry Wives of Windsor ACT I SCENE I. Windsor. Before PAGE's house. BLOCK I Enter SHALLOW, SLENDER, and SIR HUGH EVANS SHALLOW Sir Hugh, persuade me not; I will make a Star-chamber matter of it: if he were twenty Sir John Falstaffs, he shall not abuse Robert Shallow, esquire. SIR HUGH EVANS If Sir John Falstaff have committed disparagements unto you, I am of the church, and will be glad to do my benevolence to make atonements and compremises between you. SHALLOW Ha! o' my life, if I were young again, the sword should end it. SIR HUGH EVANS It is petter that friends is the sword, and end it: and there is also another device in my prain, there is Anne Page, which is daughter to Master Thomas Page, which is pretty virginity. SLENDER Mistress Anne Page? She has brown hair, and speaks small like a woman. SIR HUGH EVANS It is that fery person for all the orld, and seven hundred pounds of moneys, is hers, when she is seventeen years old: it were a goot motion if we leave our pribbles and prabbles, and desire a marriage between Master Abraham and Mistress Anne Page. SLENDER Did her grandsire leave her seven hundred pound? SIR HUGH EVANS Ay, and her father is make her a petter penny. SHALLOW I know the young gentlewoman; she has good gifts. SIR HUGH EVANS Seven hundred pounds and possibilities is goot gifts. Enter PAGE SHALLOW Well, let us see honest Master Page. PAGE I am glad to see your worships well. -

Henry IV, Part 2, Continues the Story of Henry IV, Part I

Folger Shakespeare Library https://shakespeare.folger.edu/ Get even more from the Folger You can get your own copy of this text to keep. Purchase a full copy to get the text, plus explanatory notes, illustrations, and more. Buy a copy Contents From the Director of the Folger Shakespeare Library Front Textual Introduction Matter Synopsis Characters in the Play Induction Scene 1 ACT 1 Scene 2 Scene 3 Scene 1 Scene 2 ACT 2 Scene 3 Scene 4 Scene 1 ACT 3 Scene 2 Scene 1 ACT 4 Scene 2 Scene 3 Scene 1 Scene 2 ACT 5 Scene 3 Scene 4 Scene 5 Epilogue From the Director of the Folger Shakespeare Library It is hard to imagine a world without Shakespeare. Since their composition four hundred years ago, Shakespeare’s plays and poems have traveled the globe, inviting those who see and read his works to make them their own. Readers of the New Folger Editions are part of this ongoing process of “taking up Shakespeare,” finding our own thoughts and feelings in language that strikes us as old or unusual and, for that very reason, new. We still struggle to keep up with a writer who could think a mile a minute, whose words paint pictures that shift like clouds. These expertly edited texts are presented to the public as a resource for study, artistic adaptation, and enjoyment. By making the classic texts of the New Folger Editions available in electronic form as The Folger Shakespeare (formerly Folger Digital Texts), we place a trusted resource in the hands of anyone who wants them. -

By William Shakespeare HENRY V 'I Think the King Is but a Man'

stf-theatre.org.uk HENRY V by William Shakespeare ‘I think the king is but a man’ Design & illustration by Future Kings HENRY V stf-theatre.org.uk 2018 1 stf-theatre.org.uk CONTENTS THE CHARACTERS PAGE 3 HENRY V SCENE-BY-SCENESCENE BY SCENE PAGE 7 DIRECTOR’S NOTEDIRECTOR’S NOTE PAGE13 HENRY V - FAMILY TREE PAGE15 DESIGN PAGE16 PERFORMANCE PAGE18 SOME QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION PAGE 21 HENRY V 2 stf-theatre.org.uk The characters THE CHORUS The Chorus: introduces the play and guides us through the story. She moves the scenes from place to place or jumps over time. She also asks the audience to imagine some of the things which simple theatre can’t show. THE ENGLISH COURT King Henry: the young, recently crowned king of England. As a young prince he lived a wild life getting drunk with Sir John Falstaff and his companions and when the play begins he is still struggling to come to terms with his new role. He is intelligent, articulate and passionate and during the play he learns how difficult it is to take responsibility as a leader. He does not always make the right decisions but wins through a combination of determination, openness and luck. Exeter: a loyal advisor to the king. She is with Henry in battle but is also a trusted envoy to the French court and present at the final peace negotiations. York: is Henry’s cousin. He is loyal and impetuous and his death at Agincourt moves Henry to tears. Cambridge: a close friend of the king, who plots with the French to assassinate Henry. -

1989 Illinois Shakespeare Festival Program School of Theatre and Dance Illinois State University

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Illinois Shakespeare Festival Fine Arts Summer 1989 1989 Illinois Shakespeare Festival Program School of Theatre and Dance Illinois State University Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/isf Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation School of Theatre and Dance, "1989 Illinois Shakespeare Festival Program" (1989). Illinois Shakespeare Festival. 8. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/isf/8 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Fine Arts at ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Illinois Shakespeare Festival by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The 1989 Illinois Shakespeare I Illinois State University Illinois Shakespeare Festival Dear friends and patrons, Welcome to the twelfth annual Illinois Shakespeare Festival. In honor of his great contributions to the Festival, we dedicate this season to the memory of Douglas Harris, our friend, colleague and teacher. Douglas died in a plane crash in the fall of 1988 after having directed an immensely successful production of Richard III last summer. His contributions and inspiration will be missed by many of us, staff and audience alike. We look forward to the opportunity to share this season's wonderful plays, including our first non-Shakespeare play. For 1989 and 1990 we intend to experiment with performing classical Illinois State University plays in addition to Shakespeare that are suited to our acting company and to our theatre space. Office of the President We are excited about the experiment and will STATE OF ILLINOIS look forward to your responses. -

The Merry Wives of Windsor ABRIDGED

1 The Merry Wives of Windsor ABRIDGED William Shakespeare Written by William Shakespeare Edited by Jane Tanner 2 3 William Shakespeare’s The Merry Wives of Windsor Edited by Jane Tanner The Wichita Shakespeare Co. 4 THE MERRY WIVES OF WINDSOR Dramatis Personae SIR JOHN FALSTAFF. PISTOL Follower of Falstaff. NYM, Follower of Falstaff. ROBIN, Page to Falstaff. MASTER FORD, Gentlemen dwelling at Windsor. MISTRESS FORD, His wife. MASTER PAGE, Gentlemen dwelling at Windsor. MISTRESS PAGE, His wife. MISTRESS ANNE PAGE, Their daughter. FENTON, a young Gentleman. SHALLOW, a Country Justice. SLENDER, Cousin to Shallow. SIMPLE, Servant to Slender. SIR HUGH EVANS, a Welsh Parson. DOCTOR CAIUS, a French Physician. MISTRESS QUICKLY, Servant to Doctor Caius. JOHN RUGBY, Servant to Doctor Caius. HOST of the Garter Inn. 5 THE MERRY WIVES OF WINDSOR List of scenes ACT I Page Scene 1 Windsor. Before PAGE's house. 7 Scene 3 A room in the Garter Inn. 12 Scene 4 A room in DOCTOR CAIUS' house. 15 ACT II Scene 1 Before PAGE'S house. 21 Scene 2 A room in the Garter Inn. 26 Scene 3 A field near Windsor. 34 ACT III Scene 1 A field near Frogmore. 37 Scene 2 A street. 40 Scene 3 A room in FORD'S house. 43 Scene 4 A room in PAGE'S house. 50 Scene 5 A room in the Garter Inn. 54 ACT IV Scene 2 A room in FORD'S house. 59 Scene 4 A room in FORD'S house. 66 Scene 5 A room in the Garter Inn. 68 Scene 6 Another room in the Garter Inn. -

Political Legitimacy and the Economy of Honor in Shakespeare's Henriad Bandana Singh Scripps College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2018 “Your unthought of Harry”: Political Legitimacy and the Economy of Honor in Shakespeare's Henriad Bandana Singh Scripps College Recommended Citation Singh, Bandana, "“Your unthought of Harry”: Political Legitimacy and the Economy of Honor in Shakespeare's Henriad" (2018). Scripps Senior Theses. 1140. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/1140 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “YOUR UNTHOUGHT OF HARRY”: POLITICAL LEGITIMACY AND THE ECONOMY OF HONOR IN SHAKESPEARE’S HENRIAD by BANDANA SINGH SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS PROFESSOR PRAKAS PROFESSOR KOENIGS 6 DECEMBER, 2017 !1 Shakespeare’s Henriad delves into questions of divine authority, political legitimacy, and kingly identity.1 While it is unknown whether Shakespeare meant for the plays to be understood as a tetralogy, each play sets up the political climate for the subsequent one. However, the Henriad also tracks a pivotal transition in the understanding and composition of kingship. Richard II paints the portrait of a king infatuated with his own divinity. Richard’s incompetency as a ruler is highlighted by two major offenses: killing his uncle Gloucester, and disinheriting his cousin, Henry Bolingbroke, who eventually leads a rebellion against the corrupted king. Richard’s journey from anointed king to deposed mortal captures the dissolution of his fantasy of invincibility and highlights two conflicting viewpoints on the office of kingship in relation to political theology. -

The Merry Wives of Windsor, Fat, Disreputable Sir John Falstaff Pursues Two Housewives, Mistress Ford and Mistress Page, Who Outwit and Humiliate Him Instead

Folger Shakespeare Library https://shakespeare.folger.edu/ Get even more from the Folger You can get your own copy of this text to keep. Purchase a full copy to get the text, plus explanatory notes, illustrations, and more. Buy a copy Contents From the Director of the Folger Shakespeare Library Front Textual Introduction Matter Synopsis Characters in the Play Scene 1 Scene 2 ACT 1 Scene 3 Scene 4 Scene 1 ACT 2 Scene 2 Scene 3 Scene 1 Scene 2 ACT 3 Scene 3 Scene 4 Scene 5 Scene 1 Scene 2 Scene 3 ACT 4 Scene 4 Scene 5 Scene 6 Scene 1 Scene 2 ACT 5 Scene 3 Scene 4 Scene 5 From the Director of the Folger Shakespeare Library It is hard to imagine a world without Shakespeare. Since their composition four hundred years ago, Shakespeare’s plays and poems have traveled the globe, inviting those who see and read his works to make them their own. Readers of the New Folger Editions are part of this ongoing process of “taking up Shakespeare,” finding our own thoughts and feelings in language that strikes us as old or unusual and, for that very reason, new. We still struggle to keep up with a writer who could think a mile a minute, whose words paint pictures that shift like clouds. These expertly edited texts are presented to the public as a resource for study, artistic adaptation, and enjoyment. By making the classic texts of the New Folger Editions available in electronic form as The Folger Shakespeare (formerly Folger Digital Texts), we place a trusted resource in the hands of anyone who wants them. -

2016 Study Guide

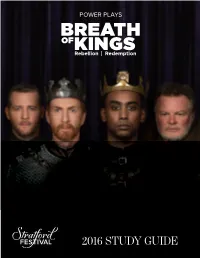

2016 STUDY ProductionGUIDE Sponsor 2016 STUDY GUIDE EDUCATION PROGRAM PARTNER BREATH OF KINGS: REBELLION | REDEMPTION BY WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE CONCEIVED AND ADAPTED BY GRAHAM ABBEY WORLD PREMIÈRE COMMISSIONED BY THE STRATFORD FESTIVAL DIRECTORS MITCHELL CUSHMAN AND WEYNI MENGESHA TOOLS FOR TEACHERS sponsored by PRODUCTION SUPPORT is generously provided by The Brian Linehan Charitable Foundation and by Martie & Bob Sachs INDIVIDUAL THEATRE SPONSORS Support for the 2016 Support for the 2016 Support for the 2016 Support for the 2016 season of the Festival season of the Avon season of the Tom season of the Studio Theatre is generously Theatre is generously Patterson Theatre is Theatre is generously provided by provided by the generously provided by provided by Claire & Daniel Birmingham family Richard Rooney & Sandra & Jim Pitblado Bernstein Laura Dinner CORPORATE THEATRE PARTNER Sponsor for the 2016 season of the Tom Patterson Theatre Cover: From left: Graham Abbey, Tom Rooney, Araya Mengesha, Geraint Wyn Davies.. Photography by Don Dixon. Table of Contents The Place The Stratford Festival Story ........................................................................................ 1 The Play The Playwright: William Shakespeare ........................................................................ 3 A Shakespearean Timeline ......................................................................................... 4 Plot Synopsis .............................................................................................................. -

Character and Idiom in Shakespeare's the Merry Wives of Windsor

Angelika Zirker Language Play in Translation: Character and Idiom in Shakespeare’s The Merry Wives of Windsor Abstract: Shakespeare’s comedy The Merry Wives of Windsor (first performed in 1597) has been commented on widely in the context of bilingual punning be- cause of the Latin lesson and translation scene at the beginning of act four. This essay focuses on character-specific language play and its translation into Ger- man over time (i.e. since the late eighteenth century to the most recent transla- tion by Frank Günther in 2012). The examples refer to three characters: Nim, Mistress Quickly, and Sir Hugh Evans. The character of Nim presents a problem to translators as he constantly re- fers to “humour” in an undifferentiated manner, i.e. on all kinds of occasions but with different connotations. With regard to the specific idiom of Mistress Quickly and her use of malapropism, more recent German editions have tended towards substitution and interpretation rather than translation. Sir Hugh Evans poses a double problem to the translator: for one, Shakespeare marks his accent to be Welsh; moreover, Evans speaks an idiolect that is yet again different from that of Nim and Mistress Quickly, including word formation, wrong or strange grammar, overly complex syntax and wrongly understood idioms. Translators have approached his character in various ways, for instance, by having him speak in a German dialect or by inventing a “new” dialect, which, however, may lead to confusion and incomprehensibility. The survey of language play in translations of The Merry Wives of Windsor foregrounds how wordplay, character, and translation can be linked to each other.