Rapid Response Transcript – Danny Meyer Ten

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mos Rapid Response Script – Danny Meyer Interview Click Here to Listen

MoS Rapid Response Script – Danny Meyer Interview Click here to listen to the full episode with Danny Meyer. DANNY MEYER: This virus has done a superb job of exposing a lot of the preexisting conditions that our industry had. We're down to 75 people right now – which, by the way, is fewer people than I employed when I was 27, when I first got into this business. Part of the thing that America is learning is that restaurants play a massively important role in the whole economy of our country. We're throwing a lot of pasta up against the wall and we're going to see what sticks. Being the first to close is one thing – but I don't want to be the last to open. Every day we lose money could lead to even more layoffs, which is exactly the opposite of what we want to do morale-wise, emotionally, or economically. BOB SAFIAN: That’s Danny Meyer, New York City’s pre-eminent restaurateur and the founder of Shake Shack. Forced by the pandemic to close iconic restaurants like Gramercy Tavern and Union Square Cafe, Danny is now radically rethinking his business model, trying to re-image the future of restaurants without killing off the warm hospitality that made his establishments so endearing. I’m Bob Safian, former editor of Fast Company, founder of The Flux Group, and host of Masters of Scale: Rapid Response. Danny was a guest on this show at the very beginning, when the Great Lockdown first began, after laying off 2,000 of his employees. -

@Tomcolicchio + @Gailsimmons Talk Food and Temple Court in New Downtown Alliance Video

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Elizabeth Lutz, 212.835.2763, [email protected] @TomColicchio + @GailSimmons Talk Food and Temple Court in New Downtown Alliance Video NEW YORK (March 1, 2018) – Chef and Restaurateur Tom Colicchio sat down with fellow Top Chef judge Gail Simmons for an inside look at his restaurant Temple Court in the latest video from The Alliance for Downtown New York. Located in The Beekman Hotel, Temple Court has earned high marks for both Chef Colicchio's signature style and seasonal take on classic dishes as well as for the restaurant and bar's meticulously appointed decor. Here he tells us how the restaurant pays homage to the neighborhood's history. Watch the video at: http://twn.nyc/TempleCourt "A lot of what we do here at Temple Court starts with this idea of bringing back the classics and making them modern. It's all a metaphor for what's going on Downtown. What's old is new, what's new is old - it's all coming back again," notes Chef/Owner Colicchio. "Walking from the Oculus to Temple Court, you can literally visit the future and the past of Lower Manhattan within 15 minutes," adds Simmons. Temple Court was one of the most highly anticipated restaurant openings in Lower Manhattan and is part of the wave of established names and up-and-coming food stars joining the neighborhood's ranks. On the horizon, additional Lower Manhattan restaurant openings will include projects from: - Andrew Carmellini (The Dutch), - Jean-Georges Vongerichten (ABC Kitchen, Jean-Georges), - Daniel Humm and Will Guidara (Eleven Madison Park), - Danny Meyer (Gramercy Tavern), - David Chang (Momofuku) and - James Kent (Nomad). -

What's Happening In

What’s happening in Fall 2020 Washington, CT Message from the Shepaug Regional School District 12 Selectmen’s Office Regional School District 12 is deeply appreciative of the support, care and generosity our community gave to our students and staff. We would like As we continue to navigate the COVID-19 pandemic, to thank the leadership of First Selectman Jim Brinton, our town leaders I often reflect on how we as individuals, as well as a and Board of Education members who helped guide us through this community, have handled this crisis. I’m always left pandemic. Our town leaders continue to protect, support and carry us feeling very proud of our town. While we have not through a very difficult time. remained untouched by the tragedies of coronavirus, we have continued to embrace the values that make The Shepaug graduation parade in June was a wonderful illustration of Washington unique. All of our residents have come the community support of our students. Shepaug seniors began their together to meet the needs of the community. Our graduation journey at Shepaug Valley School. The parade of cars traveled businesses, cultural centers, schools, nonprofit through the three towns. Our community members lined the streets organizations and houses of worship have all met the (using social distance) and made our graduating seniors feel honored and challenges we’ve faced since the outbreak. celebrated. Our Shepaug seniors arrived on the Bridgewater Fairgrounds in their family cars. Our students were celebrated with honking horns, One of the biggest hurdles our community is currently cheers, fireworks and confetti cannons. -

How Does Danny Meyer Do

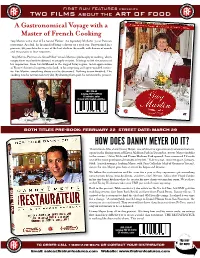

FIRST RUN FEATURES pRESENTS TWO FILMS ABOUT THE ART OF FOOD A Gastronomical Voyage with a Master of French Cooking Guy Martin is the chef of Le Grand Véfour, the legendary Michelin 3-star Parisian restaurant. As a kid, he dreamed of being a doctor or a rock star. First trained in a pizzeria, 20 years later he is one of the best chefs in the world, with dozens of awards and restaurants in four countries. “Guy Martin: Portrait of a Grand Chef” reveals Martin’s philosophy of cooking, which ranges from resolutely traditional to savagely creative. It brings to life the sources of his inspiration, from his childhood in the rugged Savoy region, to his appreciation of France’s historical supremacy in food, to his surprising and open-minded curios- ity. For Martin, everything always is to be discovered. Nothing is ever finished. The cooking is to be reinvented every day. By drawing from past, he reinvents the present. SRP: $24.95 Catalog: FRF 914598D 52 minutes, color French with English subtitles BOTH TITLES PRE-BOOK: February 22 STREET DATE: March 29 HOW DOES DANNY MEYER DO IT? This intimate film about Danny Meyer, one of America’s preeminent restaurant owners, opens in the dining room of Eleven Madison Park in December, 2009. Meyer confides to the camera: “After Tabla and Eleven Madison Park opened, I was convinced I’d made one of the worst professional mistakes of my life.” Fade to a vast, concrete space, January, 1998. A much younger-looking Meyer, with Tom Colicchio (chef of Gramercy Tavern), enters the site; Meyer gives him a tour of his hopes and dreams. -

The New Nomadic Lifestyle: Luxury Real Estate and Restaurants Take Over Nomad

6sqft.com February 15, 2018 The New Nomadic Lifestyle: Luxury Real Estate and Restaurants Take Over Nomad By Michelle Colman Impressions 151,089 nomad is defined as “a member of a community of people who live in different locations, moving from one place to another in search of grasslands for their animals.” But it would be hard to imagine any Nomad resident ever straying for Agrasslands beyond Madison Square Park. After a series of incarnations over the years, Nomad is now a super hip, bustling neighborhood from morning through night with residents, technology businesses (it’s now being referred to as “Silicon Alley”), loads of retail (leaning heavily toward design), great architecture, hot hotels, and tons and tons of food. Named for its location north of Madison Square Park, Nomad’s borders are a bit fuzzy but generally, they run east-west from Lexington Avenue to Sixth Avenue and north- 6sqft.com February 15, 2018 south from 23rd to 33rd Streets. Douglas Elliman’s Bruce Ehrmann says, “Nomad is the great link between Madison Square Park, Midtown South, Murray Hill and 5th Avenue.” Nomad’s many lives Via NYPL In the early 19th century, Nomad was known as “Satan’s Circus” for the proliferation of bars, prostitutes and gambling. It wasn’t all unsavory activity, though, because on Christmas Eve, all the brothels’ proceeds went to charity. In its next incarnation, stately brownstones and social lunches at Delmonico’s dominated the neighborhood. Later, Nomad became known for the cluster of wholesale stores along Broadway. Today, it’s a hotbed of cool architecture, luxury condo buildings, high-end hotels, and world class restaurants. -

Masters of Scale Episode Transcript: Danny Meyer DANNY MEYER: I

Masters of Scale Episode Transcript: Danny Meyer DANNY MEYER: I had spent three or four years selling electronic tags to stop shoplifters, which was basically my ticket to living in New York, and it turned out I was a really good salesman. I was completely ignorant to my own burning passion. REID HOFFMAN: That’s Danny Meyer, recounting his former life as a crime-fighter of sorts in the rough-and-tumble of early 80s Gotham. And like many troubled heroes, he was haunted by his past, and uncertain of his future. MEYER: I decided I should opt towards getting a law degree. HOFFMAN: After months of grueling study, he was finally ready to sit the test that would set him on course for a comfortable life in law. MEYER: The night before I took my LSATs, I had dinner with my aunt and uncle and my grandmother, at an Italian restaurant here in New York City. I was in a foul mood and my uncle turned to me and he said, “What the hell's eating you anyway?” And I said, “Well, I gotta take my LSATs tomorrow.” He said, “Well, duh, you want to be a lawyer, of course you're gonna take your LSATs.” And I said something really stupid to him at that point, which changed my entire life, which was, “I don't really want to be a lawyer.” He got furious with me. He said, “Do you not realize that you're going to be dead forever?” And I said, “What do you mean?” He said, “Do you not realize that relative to how long you're gonna be dead, you're gonna be alive for about a minute? Why in the world would you do something that you don't want to do?” And I said, “Well, I don't know what else I would do.” He said, “You gotta be kidding me. -

Shop. Eat. Drink. Play

Tickets available at ONEWORLDOBSERVATORY.COM SHOP. HOW DO YOU GET TO THE TOP OF THE CITY’S TALLEST BUILDING? EAT. IN A SKYPOD, OF COURSE. DRINK. PLAY. ALL UNDER ONE Guide Manhattan Shop Dine Lower MAGNIFICENT ROOF. At the corner of Church St. and Dey St. LOWER MANHATTAN SHOP DINE GUIDE 2018 | 2018 DOWN IS WHAT’S UP!TM @ONEWORLDNYC BANANA REPUBLIC | EATALY | FOREVER 21 #ONEWORLDVIEW SEPHORA | UGG | VICTORIA’S SECRET Where the Palm Trees Grow. Fashion. Food. Art Vesey & West St When it comes to fashion and beauty, we are now poised to become one of the pre-eminent shopping destinations in the region. A year after the Oculus and Westfield World Trade Center opened, Saks Men (following on the heels of Saks Women), Marshalls, Dior Cosmetics, and Allen Edmonds joined T.J. Maxx, Century 21, and the shops at Brookfield Place. What will next year bring? Looking ahead, restaurateurs Jean-Georges Vongerichten, Danny Meyer, and the duo of Will Guidara and Daniel Humm plan to open new restaurants in Lower Manhattan. And when Alamo Drafthouse opens its doors to moviegoers at 28 Liberty, it will join the Seaport’s iPic Theater in making the neighborhood a destination for those SHOPPING who want to mix great food and drink with catching a flick. Just like you can’t tell the players in a baseball game without a scorecard, sometimes it can be hard to keep track of all the & DINING new options in the neighborhood. With that in mind, we present you with the Downtown Alliance’s 2018 Lower Manhattan IN LOWER MANHATTAN Shop Dine Guide -- your best source for shops, eateries, bars, From the Statue of Liberty to the observation deck at One museums, community resources, attractions and more. -

For Immediate Release

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: DANNY MEYER TO RECEIVE THE TORCH AWARD AT 2017 INTERNATIONAL RESTAURANT & FOODSERVICE SHOW OF NEW YORK FROM MASTER CHEF FERDINAND METZ Registration Now Open for Event, Scheduled for March 5-7 in New York City New York, NY, December 13, 2016 - Danny Meyer, CEO of Union Square Hospitality Group and the founder of Shake Shack will receive the TORCH Award during the upcoming International Restaurant & Foodservice Show of New York (Sunday, March 5 - Tuesday, March 7, 2017 at the Javits Center in New York). The Torch Award, presented by The Food Shows and Ferdinand Metz Foodservice Forum, was created to honor outstanding restaurateurs who embody all the qualities and characteristics of the word Torch which symbolizes, including illumination, energy, joy, victory, enlightenment, hope and education. As a restaurateur extraordinaire and enlightened hospitality guru, Danny Meyer's ability to teach and share clearly demonstrates the definition of the Torch. "Since the start of his career 30 years ago, Meyer has launched a number of highly successful restaurants with locations throughout the country, and is an exemplary leader in the restaurant industry," said Master Chef Metz. "We are thrilled to present Danny with this prestigious award for his commitment to the industry, his teams, the public they serve, and the communities they support." Union Square Hospitality Group includes Union Square Cafe, Gramercy Tavern, Blue Smoke, Jazz Standard, The Modern, Maialino, Untitled, North End Grill, Marta, Porchlight, Union Square Events, and Hospitality Quotient, a learning and consulting business. Danny, his restaurants and chefs have earned an unprecedented 28 James Beard Awards, and in 2015, Danny was named to the TIME 100 list of the Most Influential People in the World. -

Public Art Works

Public Art Works SEASON 1 - EPISODE #2 FOOD FOR THOUGHT—AND ART Susan K. Freedman, Danny Meyer, Erwin Wurm & Joe DiStefano TRT 28:00 JEFFREY WRIGHT: Hi everybody. I’m your host, Jeffrey Wright. And welcome back to the Public Art Fund podcast Public Art Works, where we use public art as a means of jumpstarting broader conversations about New York City, our history, and our current moment. JEFFREY WRIGHT: We’re talking art and food today, but before we get into the meat of things let’s, well, get into the meat of things. And hear what both New Yorkers and visitors to New York had to say about the intersection of food and art recently while queuing up at the original Shake Shack in Madison Square Park. PUBLIC VOICE 1: Street food is just like public art, you know, because it’s everywhere. PUBLIC VOICE 2: It’s a very creative process, putting different ingredients together and how you present it. There’s an art and a science to it definitely both. PUBLIC VOICE 3: Yeah definitely does help represent that New York is a melting pot and you can experience so many different cultures from looking at art, and also definitely by eating food. PUBLIC VOICE 4: They’re both a platform for people to create something for others to experience. PUBLIC VOICE 5: Food is something we share. Everybody has to eat, so that’s a quite democratic start. But uh art is maybe… it requires a bit more attention PUBLIC VOICE 6: Like, you know when you see a halal cart like one of those hot dog stands or pretzel stands you’re drawn by the smell, right? When it comes to art you’re drawn by the sight of it. -

Print Profile

Danny Meyer is the CEO of Union Square Hospitality Group, which includes Union Square Cafe, Gramercy Tavern, Blue Smoke, Jazz Standard, Shake Shack, The Danny Meyer Modern, Cafe 2 and Terrace 5 (at the Museum of Modern Art), Maialino, Untitled (at the Whitney Museum of American Art), and North End Grill, as well as Union Square Events and Hospitality Quotient. Each USHG restaurant and business is Speech Topics lovingly crafted and distinctive, and each strives to distinguish itself with warm hospitality and consistent excellence. Retail Born and raised in St. Louis, Missouri, Danny Meyer grew up in a family that Management relished great food, cooking, get-togethers, travel and hospitality. Thanks to his Leadership father’s travel business, he spent much of his childhood eating, visiting near and Human Resources far-off places, and sowing the seeds for his future passion for food, wine, and a Entrepreneur successful career in the hospitality industry. Customer Service Danny worked for his father as a tour guide in Rome during college, and then returned to the Eternal City to study international politics. He minored in the study of trattorias, spending at least as much time at the table as he did in the classroom. After graduating from Trinity College with a degree in political science, Danny landed in Chicago and took a job as Cook County Field Director for John Anderson’s 1980 independent presidential campaign. Pursuing his true passions for food and wine, Danny later gained his first restaurant experience in 1984 as an assistant manager at Pesca, an Italian seafood restaurant in the Flatiron District of New York City. -

Press File 2

Press Notices The Clarett Group AUGUST 20, 2010 Press Notices The Clarett Group MAY 30, 2010 subsidized housing with his mother and He hoped for a one-bedroom in an elevator A Veteran Goes three of her grandchildren. “We lived in building with a doorman and a gym. “I an apartment without air-conditioning, so didn’t want to feel like I felt when I was House-Hunting on it was always hot,” he said. “It was in the living in government housing,” he said. “I the G.I. Bill worst part of town.” planned for a long time not to have to go back to that.” By JOYCE COHEN After high school, he joined the Army, “to elevate my standard of living,” he said. Beyond that, he didn’t want to live on a THOUGH Willie Holmes had been While serving, he received a degree in high floor. “If anything goes wrong, I want traveling back and forth to New York for a health-care management. “I wanted to help to be able to take the stairs,” he said. And few years, primarily for modeling jobs, he and not to kill,” he said. the bedroom needed to be large enough had little knowledge of the city’s housing for a queen-size bed. “I am 6-2, so I didn’t market — just vague impressions from his Most recently, living in a basement want to have to sleep in a small bed. I did New York friends, most of whom lived in apartment in Maryland, he “saved up enough of that in the Army. -

View to the Catering Field

Daniel Meyer CEO, Union Square Hospitality Group Daniel ("Danny") Meyer is the CEO of the Union Square Hospitality Group, which includes Union Square Cafe, Gramercy Tavern, Eleven Madison Park, Tabla, Blue Smoke, Jazz Standard, Shake Shack, and The Modern, Cafe 2, Terrace 5 at the newly renovated Museum of Modern Art, and Hudson Yards Catering. Danny Meyer grew up in a family that relished great food, cooking, get-togethers, travel, and hospitality. Thanks to his father’s travel business, he spent much of his childhood eating, traveling to near and far-off places, and sewing the seeds for his future passion for food, wine, and a successful career in the restaurant and hospitality industry. Danny worked for his father as a tour guide in Rome during college, and then returned to the Eternal City to study international politics. He minored in the study of trattorias, spending at least as much time at the table as he did in the classroom. After graduating from Trinity College with a degree in Political Science, Danny landed in Chicago and took a job as Cook County Field Director for John Anderson’s 1980 independent US Presidential campaign. Pursuing his true passions for food and wine, Danny later gained his first restaurant experience in 1984 as an assistant manager at Pesca, an Italian seafood restaurant in the Flatiron District of New York City. He then returned to Europe to study cooking as a culinary stagière in both Italy and Bordeaux, France. In 1985, Danny launched Union Square Cafe, pioneering a new breed of American eatery, pairing imaginative food and wine with caring hospitality, comfortable surroundings, and outstanding value.