Fischer 2000

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

V Review of Bufflehead Sex and Age Criteria with Notes on Weights :HARLES J

V review of Bufflehead sex and age criteria with notes on weights :HARLES J. HENNY, JOHN L. CARTER, and BETTE J. CARTER The Bufflehead Bucephaia albeola is the stated that any duck, goose, or swan, re mallest diving duck in North America. A gardless of age or plumage, may be sexed ecent review by Palmer (1976) noted by the presence or absence of the penis. )otential problems regarding sex and age However, in the Bufflehead, we found that letermination which in turn leads to the penis of immatures (first-year males) loubts about the relative size among sex was very small and sometimes difficult to md age classes. The present study was ascertain; therefore, an internal check of lesigned to check the reliability of several the gonads was made for verification. In nethods used for sex and age determina- adults, the penis is larger and enclosed ion in this species. within a conspicuous sheath. We collected 87 birds during two duck In the female, the criterion of age is the lunting seasons (24 November 1978 to 14 left oviduct which empties into the cloacal anuary 1979 and 4 N ovember 1979 to 6 chamber through the left cloacal wall. In ianuary 1980) at the Salmon River estuary, immature females, the oviduct is closed by incoin County, Oregon. a membrane; the left cloacal wall is un broken. In adult females, the occluding membrane is absent; the oviduct may be »ex and age determination seen as a conspicuous slit on the left cloacal wall. >ex and/or age may be determined in In both sexes another criterion of age waterfowl in several ways: (1) general exists in the cloaca, the bursa of Fabricius. -

Cobb County, Georgia and Incorporated Areas

VOLUME 1 OF 4 Cobb County COBB COUNTY, GEORGIA AND INCORPORATED AREAS COMMUNITY NAME COMMUNITY NUMBER ACWORTH, CITY OF 130053 AUSTELL, CITY OF 130054 COBB COUNTY 130052 (UNINCORPORATED AREAS) KENNESAW, CITY OF 130055 MARIETTA, CITY OF 130226 POWDER SPRINGS, CITY OF 130056 SMYRNA, CITY OF 130057 REVISED: MARCH 4, 2013 FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY NUMBER 13067CV001D NOTICE TO FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY USERS Communities participating in the National Flood Insurance Program have established repositories of flood hazard data for floodplain management and flood insurance purposes. This Flood Insurance Study (FIS) report may not contain all data available within the Community Map Repository. Please contact the Community Map Repository for any additional data. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) may revise and republish part or all of this FIS report at any time. In addition, FEMA may revise part of this FIS report by the Letter of Map Revision process, which does not involve republication or redistribution of the FIS report. Therefore, users should consult with community officials and check the Community Map Repository to obtain the most current FIS report components. Initial Countywide FIS Effective Date: August 18, 1992 Revised Countywide FIS Effective Date: December 16, 2008 Revised Countywide FIS Effective Date: March 4, 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Purpose of Study 1 1.2 Authority and Acknowledgments 1 1.3 Coordination 3 2.0 AREA STUDIED 5 2.1 Scope of Study 5 2.2 Community Description 10 2.3 Principal Flood Problems -

List of TMDL Implementation Plans with Tmdls Organized by Basin

Latest 305(b)/303(d) List of Streams List of Stream Reaches With TMDLs and TMDL Implementation Plans - Updated June 2011 Total Maximum Daily Loadings TMDL TMDL PLAN DELIST BASIN NAME HUC10 REACH NAME LOCATION VIOLATIONS TMDL YEAR TMDL PLAN YEAR YEAR Altamaha 0307010601 Bullard Creek ~0.25 mi u/s Altamaha Road to Altamaha River Bio(sediment) TMDL 2007 09/30/2009 Altamaha 0307010601 Cobb Creek Oconee Creek to Altamaha River DO TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010601 Cobb Creek Oconee Creek to Altamaha River FC 2012 Altamaha 0307010601 Milligan Creek Uvalda to Altamaha River DO TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 2006 Altamaha 0307010601 Milligan Creek Uvalda to Altamaha River FC TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010601 Oconee Creek Headwaters to Cobb Creek DO TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010601 Oconee Creek Headwaters to Cobb Creek FC TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010602 Ten Mile Creek Little Ten Mile Creek to Altamaha River Bio F 2012 Altamaha 0307010602 Ten Mile Creek Little Ten Mile Creek to Altamaha River DO TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010603 Beards Creek Spring Branch to Altamaha River Bio F 2012 Altamaha 0307010603 Five Mile Creek Headwaters to Altamaha River Bio(sediment) TMDL 2007 09/30/2009 Altamaha 0307010603 Goose Creek U/S Rd. S1922(Walton Griffis Rd.) to Little Goose Creek FC TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010603 Mushmelon Creek Headwaters to Delbos Bay Bio F 2012 Altamaha 0307010604 Altamaha River Confluence of Oconee and Ocmulgee Rivers to ITT Rayonier -

Rule 391-3-6-.03. Water Use Classifications and Water Quality Standards

Presented below are water quality standards that are in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. EPA is posting these standards as a convenience to users and has made a reasonable effort to assure their accuracy. Additionally, EPA has made a reasonable effort to identify parts of the standards that are not approved, disapproved, or are otherwise not in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. Rule 391-3-6-.03. Water Use Classifications and Water Quality Standards ( 1) Purpose. The establishment of water quality standards. (2) W ate r Quality Enhancement: (a) The purposes and intent of the State in establishing Water Quality Standards are to provide enhancement of water quality and prevention of pollution; to protect the public health or welfare in accordance with the public interest for drinking water supplies, conservation of fish, wildlife and other beneficial aquatic life, and agricultural, industrial, recreational, and other reasonable and necessary uses and to maintain and improve the biological integrity of the waters of the State. ( b) The following paragraphs describe the three tiers of the State's waters. (i) Tier 1 - Existing instream water uses and the level of water quality necessary to protect the existing uses shall be maintained and protected. (ii) Tier 2 - Where the quality of the waters exceed levels necessary to support propagation of fish, shellfish, and wildlife and recreation in and on the water, that quality shall be maintained and protected unless the division finds, after full satisfaction of the intergovernmental coordination and public participation provisions of the division's continuing planning process, that allowing lower water quality is necessary to accommodate important economic or social development in the area in which the waters are located. -

River Clean-Up Guru, Bobby Marie…

River Clean-Up Guru, Bobby Marie… 1/11/2012 - Chattahoochee River 1/14/2012 – Etowah River 1/14/2012 – Coosa River 1/14/2012 – Oostanaula River 2/8/2012 – Peachtree Creek, South Fork 2/15/2012 – Peachtree Creek, North Fork 2/29/2012 – Suwannee River 4/21/2012 – Little River 5/16/2012 – Nickajack Creek 6/17/2012 – Altamaha River 8/8/2012 – Amicalola Creek 9/8/2012 – South River To view more 12 in 2012 finishers, go here. 1/11/2012 – Chattahoochee River Good Morning, I and two others paddled upstream on the Chattahoochee from Jones Bridge for about 4 miles then back down on a cold January afternoon on the 11th. It rained on us a couple of times, but the paddling kept us warm. We passed empty golf courses and leafless trees. We did see several herons and a couple of raptors hunting the river. Bobby Marie 1/14/2012 – Etowah, Coosa, Oostanala Rivers On January 14th, I joined Joe Cook and about 100 others on the CRBI Polar Bear Paddle over by Rome, GA. In one day I paddled 3 rivers, the Etowah for the major portion of the trip, then took two side paddles, upstream on the Oostanala for 30 minutes and then down and back up the Coosa for 30 minutes. When you reach the confluence of these three rivers you can look down and see the difference in the waters. The Etowah was greenish and the Oostanala was very brown and the Coosa was a mixture of the two! I only saw one BIG cooter on the bank in the sun the whole day. -

Colorado Field Ornithologists the Colorado Field Ornithologists' Quarterly

Journal of the Colorado Field Ornithologists The Colorado Field Ornithologists' Quarterly VOL. 36, NO. 1 Journal of the Colorado Field Ornithologists January 2002 Vol. 36, No. 1 Journal of the Colorado Field Ornithologists January 2002 TABLE OF C ONTENTS A LETTER FROM THE E DITOR..............................................................................................2 2002 CONVENTION IN DURANGO WITH KENN KAUFMANN...................................................3 CFO BOARD MEETING MINUTES: 1 DECEMBER 2001........................................................4 TREE-NESTING HABITAT OF PURPLE MARTINS IN COLORADO.................................................6 Richard T. Reynolds, David P. Kane, and Deborah M. Finch OLIN SEWALL PETTINGILL, JR.: AN APPRECIATION...........................................................14 Paul Baicich MAMMALS IN GREAT HORNED OWL PELLETS FROM BOULDER COUNTY, COLORADO............16 Rebecca E. Marvil and Alexander Cruz UPCOMING CFO FIELD TRIPS.........................................................................................23 THE SHRIKES OF DEARING ROAD, EL PASO COUNTY, COLORADO 1993-2001....................24 Susan H. Craig RING-BILLED GULLS FEEDING ON RUSSIAN-OLIVE FRUIT...................................................32 Nicholas Komar NEWS FROM THE C OLORADO BIRD R ECORDS COMMITTEE (JANUARY 2002).........................35 Tony Leukering NEWS FROM THE FIELD: THE SUMMER 2001 REPORT (JUNE - JULY)...................................36 Christopher L. Wood and Lawrence S. Semo COLORADO F IELD O -

Bufflehead Bucephala Albeola ILLINOIS RANGE

bufflehead Bucephala albeola Kingdom: Animalia FEATURES Phylum: Chordata The bufflehead is about 13 and one-half to 14 inches Class: Aves long (bill tip to tail tip in preserved specimen). The Order: Anseriformes male has black, back and wing feathers and white feathers on the remainder of the body and onto the Family: Anatidae part of the wings closest to the body. A large white ILLINOIS STATUS patch of feathers is present from below the eye to the top of the head. The remainder of the head common, native feathers are green, purple and brown. The female has dark, gray-brown feathers on her wings and body with a white-feathered cheek patch, a small, white wing patch and white belly feathers. The hind toe has a flap. The legs are located close to the tail. BEHAVIORS The bufflehead can be seen at lakes, ponds, rivers and sewage lagoons. It is a diving duck. It must run across the water's surface to take flight. This species eats small invertebrates and fishes. It is a common migrant and uncommon winter resident in Illinois. It nests in Alaska, Canada and the northern United States. ILLINOIS RANGE © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. 2020. Biodiversity of Illinois. Unless otherwise noted, photos and images © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. male female pair © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. 2020. Biodiversity of Illinois. Unless otherwise noted, photos and images © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. Aquatic Habitats bottomland forests; marshes; rivers and streams; swamps; lakes, ponds and reservoirs Woodland Habitats bottomland forests; southern Illinois lowlands Prairie and Edge Habitats edge © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. -

Energy-Based Carrying Capacities of Bufflehead Bucephala Albeola Wintering Habitats Richard A

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Natural Resources Science Faculty Publications Natural Resources Science 2012 Energy-Based Carrying Capacities of Bufflehead Bucephala albeola Wintering Habitats Richard A. McKinney Scott R. McWilliams University of Rhode Island, [email protected] Creative Commons License Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 License Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/nrs_facpubs Citation/Publisher Attribution McKinney, R. A., & McWilliams, S. R. (2012). Energy-Based Carrying Capacities of Bufflehead Bucephala albeola Wintering Habitats. The Open Ornithology Journal, 5, 5-17. doi: 10.2174/1874453201205010005 Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.2174/1874453201205010005 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Natural Resources Science at DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Natural Resources Science Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Open Ornithology Journal, 2012, 5, 5-17 5 Open Access Energy-Based Carrying Capacities of Bufflehead Bucephala albeola Wintering Habitats Richard A. McKinney*,1 and Scott R. McWilliams2 1US Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Research and Development, National Health and Environmental Effects Research Laboratory, Atlantic Ecology Division, 27 Tarzwell Drive, Narragansett, RI 02882, USA 2Department of Natural Resources Science, University of Rhode Island, Kingston, RI 02881, USA Abstract: We present a model for calculating energy-based carrying capacities for bufflehead (Bucephala albeola), a small North American sea duck wintering in coastal and estuarine habitats. Our model uses estimates of the seasonal energy expenditures that incorporate site-specific energetic costs of thermoregulation, along with available prey energy densities to calculate carrying capacities in numbers of birds per winter. -

Sauvie Island Bird Checklist Documents

WATERFOWL S S F W Cooper’s Hawk* O O O O Pectoral Sandpiper O Northern Goshawk R R Sharp-tailed Sandpiper A Tundra Swan U R U C Red-shouldered Hawk A Stilt Sandpiper A Trumpeter Swan R R R R Red-tailed Hawk* C C C C Buff-breasted Sandpiper A Greater White-fronted Goose U R U O Swainson’s Hawk A A Ruff A A Snow Goose O O U Rough-legged Hawk O O U Short-billed Dowitcher U Ross’s Goose R Long-billed Dowitcher U U U O Ferruginous Hawk A A Emperor Goose R R American Kestrel* C C C C Common Snipe* U O U C Canada Goose* C U C C Merlin O O O O Wilson’s Phalarope O R O SYMBOLS Brant O O O Prairie Falcon R R R R Red-necked Phalarope O R O S - March - May Wood Duck* C C U U Peregrine Falcon # O O O Red Phalarope A A A S - June - August Mallard* C C C C Gyrfalcon A F - September - November American Black Duck A GULLS & TERNS S S F W W - December - February Gadwall* U O U U GALLINACEOUS BIRDS S S F W # - Threatened or Endangered Species Green-winged Teal C U C C Parasitic Jaeger A * - Breeds Locally American Wigeon C U C C Ring-necked Pheasant* U O U U Franklin’s Gull A A A A Eurasian Wigeon O O O Ruffed Grouse* O O O O Bonaparte’s Gull O R O R C - Common U - Uncommon O - Occasional Northern Pintail* C U C C California Quail* R R R R Ring-billed Gull C U U C R - Rare A - Accidental Northern Shoveler* C O C C Mew Gull U O O C Blue-winged Teal* R R R R RAILS, COOTS & CRANES S S F W California Gull C O U C LOONS & GREBES S S F W Cinnamon Teal* U C U O Herring Gull U O U Canvasback O O O Virginia Rail* -

Trophic State and Metabolism in a Southeastern Piedmont Reservoir

TROPHIC STATE AND METABOLISM IN A SOUTHEASTERN PIEDMONT RESERVOIR by Mary Callie Mayhew (Under the direction of Todd C. Rasmussen) Abstract Lake Sidney Lanier is a valuable water resource in the rapidly developing region north of Atlanta, Georgia, USA. The reservoir has been managed by the U.S Army Corps of Engineers for multiple purposes since its completion in 1958. Since approximately 1990, Lake Lanier has been central to series of lawsuits in the “Eastern Water Wars” between Georgia, Alabama and Florida due to its importance as a water-storage facility within the Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint River Basin. Of specific importance is the need to protect lake water quality to satisfy regional water supply demands, as well as for recreational and environmental purposes. Recently, chlorophyll a levels have exceeded state water-quality standards. These excee- dences have prompted the Georgia Environmental Protection Division to develop Total Max- imum Daily Loads for phosphorus in Lake Lanier. While eutrophication in Southeastern Piedmont impoundments is a regional problem, nutrient cycling in these lakes does not appear to behave in a manner consistent with lakes in higher latitudes, and, hence, may not respond to nutrient-abatement strategies developed elsewhere. Although phosphorus loading to Southeastern Piedmont waterbodies is high, soluble reac- tive phosphorus concentrations are generally low and phosphorus exports from the reservoir are only a small fraction of input loads. The prevailing hypothesis is that ferric oxides in the iron-rich, clay soils of the Southeastern Piedmont effectively sequester phosphorus, which then settle into the lake benthos. Yet, seasonal algal blooms suggest the presence of internal cycling driven by uncertain mechanisms. -

Nest Box Guide for Waterfowl Nest Box Guide for Waterfowl Copyright © 2008 Ducks Unlimited Canada ISBN 978-0-9692943-8-2

Nest Box Guide for Waterfowl Nest Box Guide For Waterfowl Copyright © 2008 Ducks Unlimited Canada ISBN 978-0-9692943-8-2 Any reproduction of this present document in any form is illegal without the written authorization of Ducks Unlimited Canada. For additional copies please contact the Edmonton DUC office at (780)489-2002. Published by: Ducks Unlimited Canada www.ducks.ca Acknowledgements Photography provided by : Ducks Unlimited Canada (DUC), Jim Potter (Alberta Conservation Association (ACA)), Darwin Chambers (DUC), Jonathan Thompson (DUC), Lesley Peterson (DUC contractor), Sherry Feser (ACA), Gordon Court ( p 16 photo of Pygmy Owl), Myrna Pearman ,(Ellis Bird Farm), Bryan Shantz and Glen Rowan. Portions of this booklet are based on a Nest Box Factsheet prepared by Jim Potter (ACA) and Lesley Peterson (DUC contractor). Myrna Pearman provided editorial comment. Table of Contents Table of Contents Why Nest Boxes? ......................................................................................................1 Natural Cavities ......................................................................................................................................2 Identifying Wildlife Species That Use Your Nest Boxes .....................................3 Waterfowl ..................................................................................................................4 Common Goldeneye .........................................................................................................................5 Barrow’s Goldeneye -

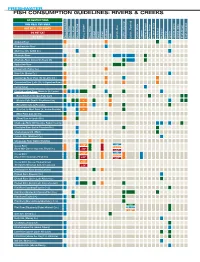

Fish Consumption Guidelines: Rivers & Creeks

FRESHWATER FISH CONSUMPTION GUIDELINES: RIVERS & CREEKS NO RESTRICTIONS ONE MEAL PER WEEK ONE MEAL PER MONTH DO NOT EAT NO DATA Bass, LargemouthBass, Other Bass, Shoal Bass, Spotted Bass, Striped Bass, White Bass, Bluegill Bowfin Buffalo Bullhead Carp Catfish, Blue Catfish, Channel Catfish,Flathead Catfish, White Crappie StripedMullet, Perch, Yellow Chain Pickerel, Redbreast Redhorse Redear Sucker Green Sunfish, Sunfish, Other Brown Trout, Rainbow Trout, Alapaha River Alapahoochee River Allatoona Crk. (Cobb Co.) Altamaha River Altamaha River (below US Route 25) Apalachee River Beaver Crk. (Taylor Co.) Brier Crk. (Burke Co.) Canoochee River (Hwy 192 to Lotts Crk.) Canoochee River (Lotts Crk. to Ogeechee River) Casey Canal Chattahoochee River (Helen to Lk. Lanier) (Buford Dam to Morgan Falls Dam) (Morgan Falls Dam to Peachtree Crk.) * (Peachtree Crk. to Pea Crk.) * (Pea Crk. to West Point Lk., below Franklin) * (West Point dam to I-85) (Oliver Dam to Upatoi Crk.) Chattooga River (NE Georgia, Rabun County) Chestatee River (below Tesnatee Riv.) Chickamauga Crk. (West) Cohulla Crk. (Whitfield Co.) Conasauga River (below Stateline) <18" Coosa River <20" 18 –32" (River Mile Zero to Hwy 100, Floyd Co.) ≥20" >32" <18" Coosa River <20" 18 –32" (Hwy 100 to Stateline, Floyd Co.) ≥20" >32" Coosa River (Coosa, Etowah below <20" Thompson-Weinman dam, Oostanaula) ≥20" Coosawattee River (below Carters) Etowah River (Dawson Co.) Etowah River (above Lake Allatoona) Etowah River (below Lake Allatoona dam) Flint River (Spalding/Fayette Cos.) Flint River (Meriwether/Upson/Pike Cos.) Flint River (Taylor Co.) Flint River (Macon/Dooly/Worth/Lee Cos.) <16" Flint River (Dougherty/Baker Mitchell Cos.) 16–30" >30" Gum Crk.