Migration and the Well-Being of Children in China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C 2014 by Lin Guo. All Rights Reserved. a NUMERICAL STUDY on MICROBUBBLE MIXER

c 2014 by Lin Guo. All rights reserved. A NUMERICAL STUDY ON MICROBUBBLE MIXER BY LIN GUO THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Mechanical Engineering in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2014 Urbana, Illinois Adviser: Associate Professor Sascha Hilgenfeldt Abstract This text comprises a numerical study of the mixing performance on the micromixer, a device which actuates steady streaming by semi-cylindrical sessile bubble oscillations. The mixer's capability of producing chaotic mixing is confirmed and a numerical simulation that is in good agreement with the experiment is developed, which then leads to the exploration of three mixing schemes. At the beginning, we introduce the experimental configuration of our micromixer, as well as the general framework of computing the asymptotic solution which is later used in numerical simulations. With these fundamentals, we proceed to characterize the efficiency of our mixer, essentially a Hamiltonian dynamical system, using Poincar´esections and the Finite-time Lyapunov exponent. These indicators provide evidence that by properly blinking between different streaming patterns, chaotic-like mixing can be created inside our mixer. The observation made from numerical results that the size of the region that is good for mixing is related to the blinking period is substantiated by a scaling argument. After showing that the micromixer is beneficial for mixing from the perspective of dynam- ical system theory, we then focus on real applications by developing passive scalar simulations that agree with experimental data well. Finally, the establishment of the simulation allows us to explore the efficiencies of three different schemes and to optimize their designs for better mixing. -

Kathy Siyu Xue, Ph.D., MPH 120 Pine Bark Ln Athens, GA 30605 (706) 353-7609 [email protected]

Kathy Siyu Xue, Ph.D., MPH 120 Pine Bark Ln Athens, GA 30605 (706) 353-7609 [email protected] EDUCATION Doctorate of Philosophy 2012-2017 Interdisciplinary Toxicology Program Athens, GA Department of Environmental Health Sciences University of Georgia Master of Public Health 2014-2017 University of Georgia Athens, GA Bachelor of Science 2008-2012 Cell and Molecular Biology Austin, TX University of Texas – Austin WORK EXPERIENCE 2017- present Postdoctoral Researcher, University of Georgia, Athens, GA. Mentor: Dr. Jia-Sheng Wang Jun. 2016 – Aug. 2016 Internship, United State Department of Agriculture Toxicology and Mycotoxin Research Unit, Athens, GA Site Supervisor: Dr. Kenneth Voss 2012-2017 Research Assistant, University of Georgia, Athens, GA. Advisor: Dr. Jia-Sheng Wang Aug.2013- Dec. 2013 Teaching Assistant, University of Georgia, Athens, GA. Taking roll, organizing student seminars, coordinating speakers Mar. 2012 – May 2012 Undergraduate Research Volunteer, Dr. Mueller Lab University of Texas – Austin, TX 2010 – 2012 Student Volunteer, Athens Regional Medical Center, Athens, GA 2010-2011 Student Research Assistant, University of Georgia – Athens, GA Dr. Jia-sheng Wang Lab Refill pipette tips, organize chemicals, shadowing research scientists. Additional work including culturing and toxicity testing for C elegans, assistance in oxidative damage biomarker analysis. 2004-2007 Student Volunteer, Texas Tech University – Lubbock, TX Dr. Jia-Sheng Wang Lab HONOR AND AWARDS 2017 Induction into Beta Chi Chapter of Delta Omega Honorary Society -

Boundary Conditions and Multi-Scale Modeling for Micro-And Nano-Flows

Boundary Conditions and Multi-Scale Modeling for Micro-and Nano-flows by Lin Guo A dissertation submitted to The Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Baltimore, Maryland March, 2016 c Lin Guo 2016 All rights reserved Abstract The development of micro- and nanofluidic devices requires detailed knowledge of interfacial phenomena. This thesis addresses two important effects at wall-fluid interfaces, boundary slip and electroosmosis, through numerical simulations. The first study uses molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to probe the influence of surface curvature on the slip boundary condition for a simple fluid. The slip length is measured for flows in planar and cylindrical geometries. As wall curvature increases, the slip length decreases dramatically for close-packed surfaces and increases slightly for sparse ones. The magnitude of the variation depends on the crystallographic orientation and the flow direction. The different patterns of behavior are related to the curvature-induced variation in the ratio of the spacing between fluid atoms to the spacing between minima in the potential from the solid surface. The results are consistent with a microscopic theory for the viscous friction between fluid and wall that expresses the slip length in terms of the lateral response of the fluid to the wall potential and the characteristic decay time of this response. The second study performs MD simulations to explore the effective slip boundary conditions over surfaces with one-dimensional sinusoidal roughness for two differ- ent flow orientations: transverse and longitudinal to the corrugations, and different atomic geometries of the wall: smoothly bent and stepped. -

The Case of Wang Wei (Ca

_full_journalsubtitle: International Journal of Chinese Studies/Revue Internationale de Sinologie _full_abbrevjournaltitle: TPAO _full_ppubnumber: ISSN 0082-5433 (print version) _full_epubnumber: ISSN 1568-5322 (online version) _full_issue: 5-6_full_issuetitle: 0 _full_alt_author_running_head (neem stramien J2 voor dit article en vul alleen 0 in hierna): Sufeng Xu _full_alt_articletitle_deel (kopregel rechts, hier invullen): The Courtesan as Famous Scholar _full_is_advance_article: 0 _full_article_language: en indien anders: engelse articletitle: 0 _full_alt_articletitle_toc: 0 T’OUNG PAO The Courtesan as Famous Scholar T’oung Pao 105 (2019) 587-630 www.brill.com/tpao 587 The Courtesan as Famous Scholar: The Case of Wang Wei (ca. 1598-ca. 1647) Sufeng Xu University of Ottawa Recent scholarship has paid special attention to late Ming courtesans as a social and cultural phenomenon. Scholars have rediscovered the many roles that courtesans played and recognized their significance in the creation of a unique cultural atmosphere in the late Ming literati world.1 However, there has been a tendency to situate the flourishing of late Ming courtesan culture within the mainstream Confucian tradition, assuming that “the late Ming courtesan” continued to be “integral to the operation of the civil-service examination, the process that re- produced the empire’s political and cultural elites,” as was the case in earlier dynasties, such as the Tang.2 This assumption has suggested a division between the world of the Chinese courtesan whose primary clientele continued to be constituted by scholar-officials until the eight- eenth century and that of her Japanese counterpart whose rise in the mid- seventeenth century was due to the decline of elitist samurai- 1) For important studies on late Ming high courtesan culture, see Kang-i Sun Chang, The Late Ming Poet Ch’en Tzu-lung: Crises of Love and Loyalism (New Haven: Yale Univ. -

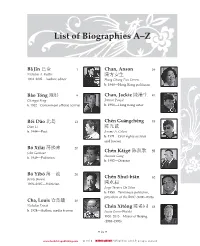

List of Biographies A–Z

fm-berkshire-dictionary-of-chinese-biography.indd Page ix 8/24/15 1:30 PM f-479 /203/BER00069/work/indd List of Biographies A–Z Baˉ Jıˉn Ꮘ䞥 1 Chan, Anson 36 Nicholas A. Kaldis 䱇ᮍᅝ⫳ 1904–2005—Author, editor Hung Chung Fun Steven b. 1940—Hong Kong politician Bào Tóng 剡ᔸ 9 Chan, Jackie 䱇␃⫳ 41 Chongyi Feng Patrice Poujol b. 1932—Government offi cial, activist b. 1954—Hong Kong actor Beˇi Daˇo ࣫ቯ 13 Chén Guaˉngchéng 48 Dian Li 䰜ܝ䆮 b. 1949—Poet Jerome A. Cohen b. 1971—Civil rights activist and lawyer Bó Xıˉlái 㭘❭ᴹ 20 䰜߃℠ 55 John Garnaut Chén Kaˇige¯ Haomin Gong b. 1949—Politician b. 1952—Director Bó Yıˉboˉ 㭘ϔ⊶ 26 62 Kerry Brown Chén Shuıˇ-biaˇn 1908–2007—Politician 䱇∈᠕ Jorge Tavares Da Silva b. 1950—Taiwanese politician, president of the ROC (2000–2008) Cha, Louis ᶹ㡃䦲 30 Nicholas Frisch Chén Xıˉtóng 䰜Ꮰৠ 68 b. 1924—Author, media tycoon Lucia Green-Weiskel 1930–2013—Mayor of Beijing (1983–1993) • ix • www.berkshirepublishing.com © 2015 Berkshire Publishing grouP, all rights reserved. fm-berkshire-dictionary-of-chinese-biography.indd Page x 14/08/15 3:54 PM F-0017 /203/BER00069/work/indd • Berkshire Dictionary of Chinese Biography • Volume 4 • Chén Yún 䰜ѥ 74 Faˉng Lìzhıˉ ᮍࢅП 123 Joel R. Campbell Kerry Brown 1905–1995—Politician, one of the 1936–2012—Physicist “Eight Immortals” Chen, Joan 䰜ކ 78 Fèi Xiàotoˉng 128 Jie Zhang 䌍ᄱ䗮 b. 1961—Actress, director Chang Xiangqun 1910–2005—Anthropologist, sociologist Cheung, Maggie 86 Féng Xiaˇogaˉng 135 ᔉ᳐⥝ ރᇣ߮ Felicia Chan Rui Zhang b. -

Newcastle 1St April

Postpositions vs. prepositions in Mandarin Chinese: The articulation of disharmony* Redouane Djamouri Waltraud Paul John Whitman [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Centre de recherches linguistiques sur l‟Asie orientale (CRLAO) Department of Linguistics EHESS - CNRS, Paris Cornell University, Ithaca, NY NINJAL, Tokyo 1. Introduction Whitman (2008) divides word order generalizations modelled on Greenberg (1963) into three types: hierarchical, derivational, and crosscategorial. The first reflect basic patterns of selection and encompass generalizations like those proposed in Cinque (1999). The second reflect constraints on synactic derivations. The third type, crosscategorial generalizations, assert the existence of non-hierarchical, non-derivational generalizations across categories (e.g. the co-patterning of V~XP with P~NP and C~TP). In common with much recent work (e.g. Kayne 1994, Newmeyer 2005), Whitman rejects generalizations of the latter type - that is, generalizations such as the Head Parameter – as components of Universal Grammar. He argues that alleged universals of this type are unfailingly statistical (cf. Dryer 1998), and thus should be explained as the result of diachronic processes, such as V > P and V > C reanalysis, rather than synchronic grammar. This view predicts, contra the Head Parameter, that „mixed‟ or „disharmonic‟ crosscategorial word order properties are permitted by UG. Sinitic languages contain well- known examples of both types. Mixed orders are exemplified by prepositions, postpositions and circumpositions occurring in the same language. Disharmonic orders found in Chinese languages include head initial VP-internal order coincident with head final NP-internal order and clause-final complementizers. Such combinations are present in Chinese languages since their earliest attestation. -

HÀNWÉN and TAIWANESE SUBJECTIVITIES: a GENEALOGY of LANGUAGE POLICIES in TAIWAN, 1895-1945 by Hsuan-Yi Huang a DISSERTATION S

HÀNWÉN AND TAIWANESE SUBJECTIVITIES: A GENEALOGY OF LANGUAGE POLICIES IN TAIWAN, 1895-1945 By Hsuan-Yi Huang A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Curriculum, Teaching, and Educational Policy—Doctor of Philosophy 2013 ABSTRACT HÀNWÉN AND TAIWANESE SUBJECTIVITIES: A GENEALOGY OF LANGUAGE POLICIES IN TAIWAN, 1895-1945 By Hsuan-Yi Huang This historical dissertation is a pedagogical project. In a critical and genealogical approach, inspired by Foucault’s genealogy and effective history and the new culture history of Sol Cohen and Hayden White, I hope pedagogically to raise awareness of the effect of history on shaping who we are and how we think about our self. I conceptualize such an historical approach as effective history as pedagogy, in which the purpose of history is to critically generate the pedagogical effects of history. This dissertation is a genealogical analysis of Taiwanese subjectivities under Japanese rule. Foucault’s theory of subjectivity, constituted by the four parts, substance of subjectivity, mode of subjectification, regimen of subjective practice, and telos of subjectification, served as a conceptual basis for my analysis of Taiwanese practices of the self-formation of a subject. Focusing on language policies in three historical events: the New Culture Movement in the 1920s, the Taiwanese Xiāngtǔ Literature Movement in the early 1930s, and the Japanization Movement during Wartime in 1937-1945, I analyzed discourses circulating within each event, particularly the possibilities/impossibilities created and shaped by discourses for Taiwanese subjectification practices. I illustrate discursive and subjectification practices that further shaped particular Taiwanese subjectivities in a particular event. -

Names of Chinese People in Singapore

101 Lodz Papers in Pragmatics 7.1 (2011): 101-133 DOI: 10.2478/v10016-011-0005-6 Lee Cher Leng Department of Chinese Studies, National University of Singapore ETHNOGRAPHY OF SINGAPORE CHINESE NAMES: RACE, RELIGION, AND REPRESENTATION Abstract Singapore Chinese is part of the Chinese Diaspora.This research shows how Singapore Chinese names reflect the Chinese naming tradition of surnames and generation names, as well as Straits Chinese influence. The names also reflect the beliefs and religion of Singapore Chinese. More significantly, a change of identity and representation is reflected in the names of earlier settlers and Singapore Chinese today. This paper aims to show the general naming traditions of Chinese in Singapore as well as a change in ideology and trends due to globalization. Keywords Singapore, Chinese, names, identity, beliefs, globalization. 1. Introduction When parents choose a name for a child, the name necessarily reflects their thoughts and aspirations with regards to the child. These thoughts and aspirations are shaped by the historical, social, cultural or spiritual setting of the time and place they are living in whether or not they are aware of them. Thus, the study of names is an important window through which one could view how these parents prefer their children to be perceived by society at large, according to the identities, roles, values, hierarchies or expectations constructed within a social space. Goodenough explains this culturally driven context of names and naming practices: Department of Chinese Studies, National University of Singapore The Shaw Foundation Building, Block AS7, Level 5 5 Arts Link, Singapore 117570 e-mail: [email protected] 102 Lee Cher Leng Ethnography of Singapore Chinese Names: Race, Religion, and Representation Different naming and address customs necessarily select different things about the self for communication and consequent emphasis. -

Lin Liu, Ph.D. Regents Professor of Physiological Sciences Lundberg

Lin Liu, Ph.D. Regents Professor of Physiological Sciences Lundberg-Kienlen Endowed Chair in Biomedical Research Director, Oklahoma Center for Respiratory and Infectious Diseases Center for Veterinary Health Sciences Oklahoma State University-Stillwater Contact Information: E-mail: [email protected] Phone: (405) 744-4526 Office: 210 McElroy Hall, Stillwater, OK 74078 Education: 1984: B.S., Chemistry, University of Science & Technology of China 1989: Ph.D., Biochemistry, Shanghai Institute of Biochemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences 1991: Postdoc, Biochemistry, Dept of Biochem and Biophys, University of Pennsylvania Med Center 1992: Postdoc, Lung Biology, Institute For Environmental Med, University of Pennsylvania Med Center Academic Appointments: 1992-1995: Research Associate, Institute for Environmental Medicine, University of Pennsylvania 1995-1997: Associate Investigator, Institute for Environmental Medicine, University of Pennsylvania 1997-2000: Research Assistant Professor, Department of Physiology, East Carolina University 2000-2004: Associate Professor, Department of Physiological Sciences, Center for Veterinary Health Sciences (CVHS), Oklahoma State University (OSU) 2004-present: Professor, Department of Physiological Sciences, CVHS, OSU 2008-present: Lundberg-Kienlen Professor/Chair in Biomedical Research, CVHS, OSU 2009-present: Regents Professor, OSU 2000-present: Director, (Lundberg-Kienlen) Lung Biology and Toxicology Lab, OSU 2010-2013: Riata Entrepreneurship Faculty Fellow, School of Entrepreneurship, OSU 2014-present: -

Lin Xue Ri B Nno Lin Xue Zh Ri B Nno G O D Ng Nong Lin Xue Xiao B N Du Jing Liu Fan D O Liang J Ng D U F Li Nong Lin Zhu N Men Xue Xiao

LIN XUE RI B NNO LIN XUE ZH RI B NNO G O D NG NONG LIN XUE XIAO B N DU JING LIU FAN D O LIANG J NG D U F LI NONG LIN ZHU N MEN XUE XIAO PDF-34LXRBNLXZRBNGODNNLXXBNDJLFDOLJNDUFLNLZNMXX2 | Page: 138 File Size 6,136 KB | 15 Mar, 2020 TABLE OF CONTENT Introduction Brief Description Main Topic Technical Note Appendix Glossary PDF File: Lin Xue Ri B Nno Lin Xue Zh Ri B Nno G O D Ng Nong Lin Xue Xiao B N Du Jing Liu Fan D O 1/3 Liang J Ng D U F Li Nong Lin Zhu N Men Xue Xiao - PDF-34LXRBNLXZRBNGODNNLXXBNDJLFDOLJNDUFLNLZNMXX2 PDF File: Lin Xue Ri B Nno Lin Xue Zh Ri B Nno G O D Ng Nong Lin Xue Xiao B N Du Jing Liu Fan D O 2/3 Liang J Ng D U F Li Nong Lin Zhu N Men Xue Xiao - PDF-34LXRBNLXZRBNGODNNLXXBNDJLFDOLJNDUFLNLZNMXX2 Lin Xue Ri B Nno Lin Xue Zh Ri B Nno G O D Ng Nong Lin Xue Xiao B N Du Jing Liu Fan D O Liang J Ng D U F Li Nong Lin Zhu N Men Xue Xiao e-Book Name : Lin Xue Ri B Nno Lin Xue Zh Ri B Nno G O D Ng Nong Lin Xue Xiao B N Du Jing Liu Fan D O Liang J Ng D U F Li Nong Lin Zhu N Men Xue Xiao - Read Lin Xue Ri B Nno Lin Xue Zh Ri B Nno G O D Ng Nong Lin Xue Xiao B N Du Jing Liu Fan D O Liang J Ng D U F Li Nong Lin Zhu N Men Xue Xiao PDF on your Android, iPhone, iPad or PC directly, the following PDF file is submitted in 15 Mar, 2020, Ebook ID PDF-34LXRBNLXZRBNGODNNLXXBNDJLFDOLJNDUFLNLZNMXX2. -

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 UMI" ARGUMENT STRUCTURE, HPSG, AND CHINESE GRAMMAR DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University by Qian Gao, B.A., M.A. ******* The Ohio State University 2001 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Carl J. Pollard, Adviser Professor Peter W. -

A Comparison of the Korean and Japanese Approaches to Foreign Family Names

15 A Comparison of the Korean and Japanese Approaches to Foreign Family Names JIN Guanglin* Abstract There are many foreign family names in Korean and Japanese genealogies. This paper is especially focused on the fact that out of approximately 280 Korean family names, roughly half are of foreign origin, and that out of those foreign family names, the majority trace their beginnings to China. In Japan, the Newly Edited Register of Family Names (新撰姓氏錄), published in 815, records that out of 1,182 aristocratic clans in the capital and its surroundings, 326 clans—approximately one-third—originated from China and Korea. Does the prevalence of foreign family names reflect migration from China to Korea, and from China and Korea to Japan? Or is it perhaps a result of Korean Sinophilia (慕華思想) and Japanese admiration for Korean and Chinese cultures? Or could there be an entirely distinct explanation? First I discuss premodern Korean and ancient Japanese foreign family names, and then I examine the formation and characteristics of these family names. Next I analyze how migration from China to Korea, as well as from China and Korea to Japan, occurred in their historical contexts. Through these studies, I derive answers to the above-mentioned questions. Key words: family names (surnames), Chinese-style family names, cultural diffusion and adoption, migration, Sinophilia in traditional Korea and Japan 1 Foreign Family Names in Premodern Korea The precise number of Korean family names varies by record. The Geography Annals of King Sejong (世宗實錄地理志, 1454), the first systematic register of Korean family names, records 265 family names, but the Survey of the Geography of Korea (東國輿地勝覽, 1486) records 277.