National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federal Register/Vol. 65, No. 214/Friday, November 3, 2000

Federal Register / Vol. 65, No. 214 / Friday, November 3, 2000 / Proposed Rules 66203 DATES: Comments must arrive by business hours. You may also see copies Division, U.S. Environmental Protection December 4, 2000. of the submitted SIP revisions at the Agency, Region 9, 75 Hawthorne Street, ADDRESSES: Mail comments to: Andrew following locations: San Francisco, CA 94105±3901, Steckel, Chief, Rulemaking Office (AIR± California Air Resources Board, telephone: (415) 744±1184. 4), Air Division, U.S. Environmental Stationary Source Division, Rule SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: The rules Protection Agency, Region IX, 75 Evaluation Section, 2020 ``L'' Street, being approved for recission and the Hawthorne Street, San Francisco, CA Sacramento, CA 95812. 94105±3901. Antelope Valley Air Pollution Control negative declarations being approved for You can inspect copies of the District, 43301 Division Street, Suite the Antelope Valley Air Pollution submitted SIP revisions and EPA's 206, Lancaster, CA 93539±4409. Control District (AVAPCD) portion of technical support documents (TSDs) at FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Julie the California SIP are listed in the our Region IX office during normal A. Rose, Rulemaking Office, AIR±4, Air following Table: SUBMITTED RECISSIONS AND NEGATIVE DECLARATIONS Adoption Submittal Rule No. and title date date Type of revision 1103, Pharmaceuticals and Cosmetic Manufacturing Operations ................. 01±18±00 03±28±00 Recission and Negative Declaration. 1159, Nitric Acid UnitsÐOxides of Nitrogen ................................................... 01±18±00 03±28±00 Recission and Negative Declaration. In the Final Rules section of this flood elevations and modified base stricter requirements of its own, or Federal Register, the EPA is approving flood elevations are the basis for the pursuant to policies established by other the state's SIP submittal as a direct final floodplain management measures that Federal, State, or regional entities. -

“Seeking a Home Where He Himself Is Free”

“Seeking A Home Where He Himself Is Free” Rebecca Brooks Harvey and her children reached Douglas County, Kansas, in January 1863 after escaping slavery in northwest Arkansas. Once in Kansas Rebecca reunited with her husband David, with whom she had lost contact during the family’s flight. The Harveys remained in the countryside near Lawrence, where David and his brother farmed “on the shares” for a white neighbor, and after five years of hard work the family had acquired fifteen acres of their own land. Image courtesy of the Kansas Collection, Kenneth Spencer Research Library, University of Kansas Libraries, Lawrence. Kansas History: A Journal of the Central Plains 31 (Autumn 2008): 154–175 154 Kansas History African Americans Build a Community in Douglas County, Kansas Katie H. Armitage ebecca Brooks Harvey and her children reached Douglas County, Kansas, in January 1863. They arrived with one hundred others who had fled enslavement in the company of General James G. Blunt’s Union army troops when they left northwest Arkansas. In the confusion of this Civil War exodus, Rebecca Harvey was separated from her husband, David Harvey, who had been Rborn a slave in Missouri and was subsequently taken to a plantation in Arkansas, where he worked as a teamster. David Harvey left Arkansas with another army division that moved north through St. Louis to Leavenworth, Kansas. After many weeks of separation and hardship, Rebecca and her children were re- united with David near Lawrence, where, with many others of similar background, they built a vibrant African American community in the symbolic capital of “free” Kansas.1 Rebecca Harvey’s journey to freedom was not unusual, harrowing as it was. -

Downtown Area Design Guidelines

CITY OF LAWRENCE DOWNTOWN AREA DESIGN GUIDELINES Including design guidelines and review criteria for THE DOWNTOWN CONSERVATION OVERLAY DISTRICT LAWRENCE’S DOWNTOWN HISTORIC DISTRICT and ENVIRONS Lawrence-Douglas County Metropolitan Planning Commission Lawrence Historic Resources Commission Lawrence, Kansas October 2008 ABOUT THE COVER Cover illustration: 1908 view of downtown Lawrence, looking Southwest. Adapted from Dary, David, Pictorial History of Lawrence, Douglas County, Kansas. Lawrence, KS: Allen Books, 1992. The Downtown Area Design Guidelines and supporting materials are available on the Law- rence-Douglas County Metropolitan Planning Office web site: www.lawrenceks.org/pds i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thanks are due to the following who helped This project was funded in make these Design Guidelines possible: part with federal funds from the National Park Service, a Mayor division of the United States Department of the Interior, Michael Dever and administered by the Kansas State Historical So- City Manager ciety. David Corliss Lawrence-Douglas County Metropolitan Planning Office Scott McCullough, Director Planning & Development Services Lynne Braddock-Zollner, Historic Resources Administrator The City of Lawrence Historic Resources Commission Jay Antle, Anne M. Marvin, Jody Meyer, Michael Sizemore (Chair), Matt Veatch, Allen Wiechart, Sean Williams The City of Lawrence Information Systems Department Special thanks for contributions by Dr. Dennis Domer, Ph.D., Baldwin, Kansas Preservation Services and Technology Group, LLC Originally compiled -

Care Coordination Resource Guide

Care Coordination Resource Guide A partner for lifelong health Resources Service vision The Care Coordination Department at LMH Health consists of a group of specially trained registered nurses and licensed social workers who are committed to providing you support through your illness and assisting you with a plan for your transition from the hospital. 4 Durable Medical Equipment/ 10 Home IV Therapy Respiratory Equipment Long-Term Acute Hospitals Acute Rehab Agencies 5 Skilled Nursing Facilities Lawrence Area 11 Skilled Nursing Facilities Olathe 6 Assisted Living Overland Park Indepentent Living Shawnee 7 Rehabilitation Services 12 Companionship/Homemaking 8 In-Home Therapy Transportation Home Health Care Area Assistance/Information Medicare Information 9 Hospice Agencies 2 | LMH Health Care Coordination Resource Guide LMH Health Phone Numbers Case Managers Rooms—201-228 785-505-5615 x75030 Rooms—3W/N 785-505-5615 x75035 Intensive Care Unit/ 2East 785-505-5615 x75032 Obstetrics/Pediatrics 785-505-5615 x75035 Emergency Department 785-505-3589 Social Workers Rooms—201-228 785-505-5615 x75029 Rooms—3W/N 785-505-5615 x75031 Acute Rehab Unit 785-505-5615 x75033 Intensive Care Unit/ 2East 785-505-5615 x75037 Obstetrics/Pediatrics 785-505-5615 x75031 Oncology 785-505-2807 Skilled Nursing 785-505-6295 Office Assistant 785-505-6149 Director 785-505-2525 If you would like to speak to one of our staff members, you may ask a nurse to contact us, or you may contact the Care Coordination Department by calling 505-6149. If you have additional concerns after being dismissed, please feel free to call us. We will be happy to assist you. -

Douglas County, Eudora & Kanwaka Intensive Survey

Eudora Township & Kanwaka Township Douglas County, Kansas Historic Resources Survey September 2015 Hernly Associates, Inc. 920 Massachusetts Street Lawrence, Kansas 66044 This study was completed in part with a Historic Preservation Fund (HPF) grant from the Kansas Historical Society, and by funding from the Douglas County Heritage Conservation Council. Buchheim Barn 3 - Kanwaka Township - Douglas County, Kansas TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................ 1-3 Purpose ........................................................................................................................................... 1 Methodology .................................................................................................................................... 1 Survey Area .................................................................................................................................... 2 Survey Findings ............................................................................................................................. 2 Survey Products ............................................................................................................................. 3 HISTORICAL SUMMARY ......................................................................................................................... 3-4 Historical Development .................................................................................................................. -

National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet

NPS Form 10-900-a OMB Approval No. 1024-0018 (8-86) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES CONTINUATION SHEET Section number 7 Page 1 Lawrence’s Downtown Commercial Historic District Douglas County, Kansas Historic Resources of Lawrence, Douglas County, Kansas SUMMARY Lawrence’s Downtown Commercial Historic District comprises the extant core of the historic central business district of Lawrence, Kansas. It is generally located along Massachusetts Street between 6th and South Park streets; see accompanying map for exact boundaries. Massachusetts Street is the primary north/south artery through the downtown. A grid-system of streets in Lawrence’s downtown runs to the four compass points. Lawrence’s downtown is located on a generally level area which slopes gently down to the Arkansas River to the south. Diagonal parking is provided along the streets, and there are wide concrete sidewalks with curbs, light standards, and stop lights at intersections. The outside edges of the district are defined either by vacant lots and parking lots, most of which were formed by the demolition of historic commercial buildings; non-historic buildings; or historic buildings which have been irreversibly altered. Most of the extant buildings in this district have identical setbacks; i.e., most are constructed to the edge of the property line along the sidewalks. Primary building materials are brick and stone. The ends of the blocks tend to be anchored with larger buildings with more monumental appearances, and smaller one- to two-story buildings are situated in the center of the block. The vast majority of buildings in the district are the commercial block property type as outlined in Section F of the multiple property submission “Historic Resources of Lawrence, Douglas County, Kansas” (hereafter referred to as “MPS”). -

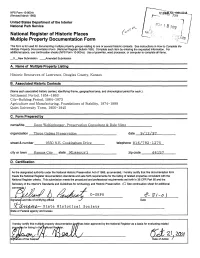

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form

NPS Form 10-900-b (Revised March 1992) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is for used for documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (National Register Bulletin 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. X__New Submission Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Historic Resources of Lawrence, Douglas County, Kansas B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) Settlement Period, 1854-1863 City-Building Period, 1864-1873 Agriculture and Manufacturing, Foundations of Stability, 1874-1899 Quiet University Town, 1900-1945 C. Form Prepared by name/title Peon Wolfenbarger. Preservation Consultant & Dale Nimz organization Three Gables Preservation date 9/12/97 street & number 9550 N.E. Cookingham Drive telephone 816/792-1275 city or town Kansas City state Missouri zip code 64157 D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60 and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards and Guidelines for Archeology and Historic Preservation. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form 1

NPS Form 10-900 (3-82) OMB No. 1024-0018 Expires 10-31-87 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only 6 National Register of Historic Places received Inventory Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections________________ 1. Name historic Case Library and or common Case Hall 2. Location street & number Baker University, Etghi-h not for publication city, town Baldwin City vicinity of state Kansas code 020 county Douglas code 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public X occupied agriculture museum x building(s) X private unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress X educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object N/A in process yes: restricted government __ scientific N/A being considered _X yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military other: name Trustees of Baker University street & number Eighth & Grove city, town Baldwin City vicinity of state Kansas 66006 5. Location off Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc.___Douglas County Courthouse street & number Massachusetts Street city, town Lawrence state Kansas fifiDAA 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title N/A has this property been determined eligible? yes _X_ no date N/A federal state county local depository for survey records N/A city, town N/A state N/A 7. Description Condition Check one Check one excellent deteriorated unaltered X original site X gOOC| ruins X altered moved date __ fair unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance Case Library (ca. 1904-1907) is located on the Baker University campus in Baldwin City, Douglas County, Kansas (pop.