Full Text (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

India Guyana Bilateral Relation

India-Guyana Bilateral Relations During the colonial period, Guyana's economy was focused on plantation agriculture, which initially depended on slave labour. Guyana saw major slave rebellions in 1763 and again in 1823.Great Britain passed the Slavery Abolition Act in British Parliament that abolished slavery in most British colonies, freeing more than 800,000 enslaved Africans in the Caribbean and South Africa. British Guiana became a Crown colony in 1928, and in 1953 it was granted home rule. In 1950, Mr. Cheddi Jagan, who was Indian-Guyanese, and Mr. Forbes Burnham, who was Afro-Guyanese, created the colony's first political party, the Progressive People's Party (PPP), which was dedicated to gaining the colony's independence. In the 1953 elections, Mr. Cheddi Jagan was elected chief minister. Mr. Cheddi Jagan of the PPP and Mr. Forbes Burnham of the PNC were to dominate Guyana politics for decades to come. In 1961, Britain granted the colony autonomy, and Mr. Cheddi Jagan became Prime Minister (1961–1964). In 1964, Burnham succeeded Jagan as Prime Minister, a position he retained after the country gained full independence on May 26, 1966. With independence, the country returned to its traditional name, Guyana. Mr. Burnham ruled Guyana until his death in 1985 (from 1980 to 1985, after a change in the constitution, he served as president). Mr. Desmond Hoyte of the PNC became president in 1985, but in 1992 the PPP reemerged, winning a majority in the general election. Mr. Cheddi Jagan became President, and succeeded in reviving the economy. After his death in 1997, his wife, Janet Jagan, was elected President. -

Tribute for Janet Jagan

Speech for the late Janet Jagan former President of Guyana at York College. Members of the head table, consul general of Guyana, Mr.Evans, ladies and gentlemen, good afternoon. We are gathered here today to pay tribute to a great lady, a lady whom I protected while she served as Prime Minister and President of Guyana. I was honored as a member of the Presidential Guards to serve in this capacity. I was selected to join the Presidential Guards after Comrade Cheddi Jagan became President in 1992 and served as one his Bodyguards until his passing in 1997. The P.P.P won a landslide victory at the polls and he became the new president of Guyana, his wife Janet, became first lady. Prime Minister Samuel Hinds was sworn in as president, Janet Jagan became prime minister, after a year, elections were held and Janet won the Presidency. Comrades here in the Diaspora I don't want you to forget as soon as Cheddi was declared winner all hell broke loose, it was former President Jimmy Carter who saved the day. During this time, I witnessed the caring, compassionate and fearlessness of this great woman, Janet Jagan. Every morning before we left for the office of the President, she would give me a bag with President Cheddi's breakfast. She would then drive to the New Guyana Company, home of the Mirror Newspaper, without Bodyguards. As First Lady, she rarely traveled around with president Cheddi, she never liked the spotlight. However, she would accompany comrade Cheddi and the grandchildren, whom she loved dearly to the swimming pool, a car was sent to pick up Kellawan Lall's and Gail Texeira's and many other kids to go along with them. -

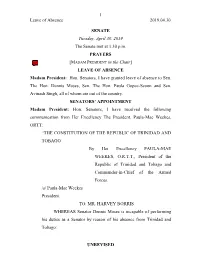

20190430, Unrevised Senate Debate

1 Leave of Absence 2019.04.30 SENATE Tuesday, April 30, 2019 The Senate met at 1.30 p.m. PRAYERS [MADAM PRESIDENT in the Chair] LEAVE OF ABSENCE Madam President: Hon. Senators, I have granted leave of absence to Sen. The Hon. Dennis Moses, Sen. The Hon. Paula Gopee-Scoon and Sen. Avinash Singh, all of whom are out of the country. SENATORS’ APPOINTMENT Madam President: Hon. Senators, I have received the following communication from Her Excellency The President, Paula-Mae Weekes, ORTT: “THE CONSTITUTION OF THE REPUBLIC OF TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO By Her Excellency PAULA-MAE WEEKES, O.R.T.T., President of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago and Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces. /s/ Paula-Mae Weekes President. TO: MR. HARVEY BORRIS WHEREAS Senator Dennis Moses is incapable of performing his duties as a Senator by reason of his absence from Trinidad and Tobago: UNREVISED 2 Senators’ Appointment (cont’d) 2019.04.30 NOW, THEREFORE, I, PAULA-MAE WEEKES, President as aforesaid, acting in accordance with the advice of the Prime Minister, in exercise of the power vested in me by section 44(1)(a) and section 44(4)(a) of the Constitution of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago, do hereby appoint you, HARVEY BORRIS, to be temporarily a member of the Senate, with effect from 30th April, 2019 and continuing during the absence from Trinidad and Tobago of the said Senator Dennis Moses. Given under my Hand and the Seal of the President of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago at the Office of the President, St. -

20010629, House Debates

29 Ombudsman Report Friday, June 29, 2001 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Friday, June 29, 2001 The House met at 1.30 p.m. PRAYERS [MR. SPEAKER in the Chair] OMBUDSMAN REPORT (TWENTY-THIRD) Mr. Speaker: Hon. Members, I have received the 23rd Annual Report of the Ombudsman for the period January 01, 2000—December 31, 2000. The report is laid on the table of the House. CONDOLENCES (Mr. Tahir Kassim Ali) Mr. Speaker: Hon. Members, it is disheartening that I announce the passing of a former representative of this honourable House, Mr. Tahir Kassim Ali. I wish to extend condolences to the bereaved family. Members of both sides of the House may wish to offer condolences to the family. The Attorney General and Minister of Legal Affairs (Hon. Ramesh Lawrence Maharaj): Mr. Speaker, the deceased, Mr. Tahir Ali served this Parliament from the period 1971—1976. He was the elected Member of Parliament for Couva. He resided in the constituency of Couva South. In addition to being a Member of Parliament, he was also a Councillor for the Couva electoral district in the Caroni County Council for the period 1968—1971. He served as Member of Parliament and Councillor as a member of the People’s National Movement. In 1974 he deputized for the hon. Shamshuddin Mohammed, now deceased, as Minister of Public Utilities for a period of time. In 1991, Mr. Tahir Ali assisted the United National Congress in the constituency of Couva South for the general election of that year. He would be remembered as a person who saw the light and came to the United National Congress. -

Memorandum of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela on The

Memorandum of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela on the Application filed before the International Court of Justice by the Cooperative of Guyana on March 29th, 2018 ANNEX Table of Contents I. Venezuela’s territorial claim and process of decolonization of the British Guyana, 1961-1965 ................................................................... 3 II. London Conference, December 9th-10th, 1965………………………15 III. Geneva Conference, February 16th-17th, 1966………………………20 IV. Intervention of Minister Iribarren Borges on the Geneva Agreement at the National Congress, March 17th, 1966……………………………25 V. The recognition of Guyana by Venezuela, May 1966 ........................ 37 VI. Mixed Commission, 1966-1970 .......................................................... 41 VII. The Protocol of Port of Spain, 1970-1982 .......................................... 49 VIII. Reactivation of the Geneva Agreement: election of means of settlement by the Secretary-General of the United Nations, 1982-198371 IX. The choice of Good Offices, 1983-1989 ............................................. 83 X. The process of Good Offices, 1989-2014 ........................................... 87 XI. Work Plan Proposal: Process of good offices in the border dispute between Guyana and Venezuela, 2013 ............................................. 116 XII. Events leading to the communiqué of the UN Secretary-General of January 30th, 2018 (2014-2018) ....................................................... 118 2 I. Venezuela’s territorial claim and Process of decolonization -

Trinidad and Tobago

Riskline / Country Report / 29 August 2021 TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO Overall risk level High Reconsider travel Can be dangerous and may present unexpected security risks Travel is possible, but there is a potential for disruptions Overview Emergency Numbers Medical 811 Upcoming Events There are no upcoming events scheduled Riskline / Country Report / 29 August 2021 / Trinidad and Tobago 2 Travel Advisories Riskline / Country Report / 29 August 2021 / Trinidad and Tobago 3 Summary Trinidad and Tobago is a High Risk destination: reconsider travel. High Risk locations can be dangerous and may present unexpected security risks. Travel is possible, but there is a potential for severe or widespread disruptions. Covid-19 High Risk A steep uptick in infections reported as part of a second wave in April-June prompted authorities to reimpose restrictions on movement and business operations. Infection rates are increasing again since July. International travel remains limited to vaccinated travellers only. Political Instability Low Risk A parliamentary democracy led by centrist Prime Minister Keith Rowley, Trinidad and Tobago's democracy is firmly entrenched thanks to a well-established system of checks and balances that helped it remain resilient in the face of sources of instability like politically motivated murders in 1980 and an Islamist coup attempt in 1990. Despite its status as a regional and economic leader in the Caribbean, the nation faces challenges of corruption allegations in the highest level of government and an extensive drug trade and associated crime that affects locals and tourists alike. Conflict Low Risk Trinidad and Tobago has been engaged in a long-standing, and at times confrontational, dispute over fishing rights with Barbados that also encompasses other resources like oil and gas. -

From Grassroots to the Airwaves Paying for Political Parties And

FROM GRASSROOTS TO THE AIRWAVES: Paying for Political Parties and Campaigns in the Caribbean OAS Inter-American Forum on Political Parties Editors Steven Griner Daniel Zovatto Published by Organization of American States (OAS) International IDEA Washington, D.C. 2005 © Organization of American States (OAS) © International IDEA First Edition, August, 2005 1,000 copies Washinton, D.C. The opinions expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the Organization of American States or the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance. Editors: Steven Griner Daniel Zovatto ISBN 0-8270-7856-4 Layout by: Compudiseño - Guatemala, C.A. Printed by: Impresos Nítidos - Guatemala, C.A. September, 2005. Acknowledgements This publication is the result of a joint effort by the Office for the Promotion of Democracy of the Organization of American States, and by International IDEA under the framework of the Inter-American Forum on Political Parties. The Inter-American Forum on Political Parties was established in 2001 to fulfill the mandates of the Inter-American Democratic Charter and the Summit of the Americas related to the strengthening and modernization of political parties. In both instruments, the Heads of State and Government noted with concern the high cost of elections and called for work to be done in this field. This study attempts to address this concern. The overall objective of this study was to provide a comparative analysis of the 34 member states of the OAS, assessing not only the normative framework of political party and campaign financing, but also how legislation is actually put into practice. -

Archival Resources Reimagined: a Feminist Examination of the "Latin American Twentieth-Century Pamphlets"

Please do not remove this page Archival Resources Reimagined: a Feminist Examination of the "Latin American Twentieth-century Pamphlets" Denda, Kayo https://scholarship.libraries.rutgers.edu/discovery/delivery/01RUT_INST:ResearchRepository/12643395980004646?l#13643549390004646 Denda, K. (2010). Archival Resources Reimagined: a Feminist Examination of the “Latin American Twentieth-century Pamphlets.” Rutgers University. https://doi.org/10.7282/T3736SJ8 This work is protected by copyright. You are free to use this resource, with proper attribution, for research and educational purposes. Other uses, such as reproduction or publication, may require the permission of the copyright holder. Downloaded On 2021/09/25 14:32:28 -0400 Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey Women’s and Gender Studies Department M. A. Practicum Report Archival Resources Reimagined: a Feminist Examination of the Latin American Twentieth-Century Pamphlets 2010 Kayo Denda Master of Arts Candidate Practicum Committee: Prof. Nancy Hewitt (adviser) Prof. Carlos U. Decena Prof. Yana van der Meulen Rodgers INTRODUCTION The attempt by feminist scholars to reframe and address questions ignored in traditional investigations has created a new demand for non-traditional resources in libraries. These non-conventional and alternative resources, often referred to as fugitive or grey literature, include a body of material that is often not identified through standard acquisitions procedures or retrieved through research tools such as indexes or catalogs. The Latin American Twentieth-Century Pamphlets (LATCP) collection at Rutgers University Libraries offers one such example. The collection includes documents that emanate from outside the dominant culture and have subversive overtones, created by non-commercial means of production and with limited distribution to a specific audience. -

Basdeo Panday Leader of the United National Congress

STRONG LEADERSHIP FOR A STRONG T&T THE UNITED NATIONAL CONGRESS Re s t o r i n g Tru s t he PNM’s unrelenting seven-year campaign and its savagely partisan Tuse of the apparatus of the State to humiliate and criminalise the leadership and prominent supporters of the UNC have failed to produce a single convic- tion on any charge of misconduct in public office. The UNC nonetheless recognises the compelling obligation to move immedi- ately with speed and purpose to do all that is possible to restore the public trust. We will therefore lose no time and spare an individual of manifestly impeccable no effort in initiating the most stringent reputation and sterling character, charged measures that will enforce on all persons with the responsibility of igniting in gov- holding positions of public trust, scrupu- ernment and in the wider national com- lous compliance with the comprehensive munity of the Republic of Trinidad and legislative and legal sanctions that the Tobago, a culture of transparency, UNC has already introduced, and will yet accountability, decency, honesty, and formulate, to ensure unwavering adher- probity, that will permit no compromise, ence to the highest ethical standards and will protect no interest save the public the most exacting demands of probity in good, and will define the politics of this all matters of Governance. nation into perpetuity. To these ends, we will appoint as Minister of Public Administration and Compliance, Basdeo Panday Leader of the United National Congress 1 THE UNITED NATIONAL CONGRESS STRONG LEADERSHIP -

Elections, Identity and Ethnic Conflict in the Caribbean the Trinidad Case

Pouvoirs dans la Caraïbe Revue du CRPLC 14 | 2004 Identité et politique dans la Caraïbe insulaire Elections, Identity and Ethnic Conflict in the Caribbean The Trinidad Case Ralph R. Premdas Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/plc/246 DOI: 10.4000/plc.246 ISSN: 2117-5209 Publisher L’Harmattan Printed version Date of publication: 14 January 2004 Number of pages: 17-61 ISBN: 2-7475-7061-4 ISSN: 1279-8657 Electronic reference Ralph R. Premdas, « Elections, Identity and Ethnic Conflict in the Caribbean », Pouvoirs dans la Caraïbe [Online], 14 | 2004, Online since 02 March 2011, connection on 19 April 2019. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/plc/246 ; DOI : 10.4000/plc.246 © Pouvoirs dans la Caraïbe ELECTIONS, IDENTITY AND ETHNIC CONFLICT IN THE CARIBBEAN: THE TRINIDAD CASE by Ralph R. PREMDAS Department of Government University of the West Indies St. Augustine Trinidad and Tobago Below the surface of Trinidad's political peace exists an antagonistic ethnic monster waiting its moment of opportunity to explode!. The image of a politically stable and economically prosperous state however conceals powerful internal contradictions in the society. Many critical tensions prowl through the body politic threatening to throw the society into turmoil. Perhaps, the most salient of these tensions derives from the country's multi-ethnic population. Among the one million, two hundred thousand citizens live four distinct ethno-racial groups: Africans, Asian Indians, Europeans and Chinese. For two centuries, these groups co-existed in Trinidad, but failed to evolve a consensus of shared values so as to engender a sense of common citizenship and a shared identity. -

Biografías Inaguración

BIOGRAFÍAS Primer Conversatorio Regional de América Latina y el Caribe “En la ruta de la Igualdad”: 30 años de la Convención sobre los Derechos del Niño HENRIETTA H. FORE Henrietta H. Fore asumió el cargo de Directora General de UNICEF el 1 de enero de 2018, convirtiéndose así en la séptima persona que ocupa este puesto. Durante una carrera que abarca más de cuatro décadas, ha trabajado para promover el desarrollo económico, la educación, la salud, la asistencia humanitaria y la ayuda en casos de desastre en los sectores público y privado, así como en diversas organizaciones sin fines de lucro. De 2007 a 2009, la Sra. Fore se desempeñó como Administradora de la Agencia de los Estados Unidos para el Desarrollo Internacional (USAID) y Directora de Asistencia Exterior de los Estados Unidos. La primera mujer en servir en estas funciones, fue responsable de administrar un presupuesto anual de 39.500 millones de dólares de asistencia extranjera de los Estados Unidos, una cifra que incluía prestar apoyo a las poblaciones y los países en las labores de recuperación después de un desastre y la construcción de un futuro económico, político y social. Al principio de su carrera en USAID, la Sra. Fore fue nombrada Administradora Auxiliar para Asia y Administradora Auxiliar para la Empresa Privada (1989-1993). También se desempeñó en las Juntas de la Corporación para Inversiones Privadas en el Extranjero y en la Corporación del Desafío del Milenio. En 2009 recibió el Premio al Servicio Distinguido, el máximo galardón que concede el Secretario de Estado. De 2005 a 2007, la Sra. -

Address to Venezuelan Legislators

ADDRESS BY HER EXCELLENCY MRS JANET JAGAN TO VENEZUELAN LEGISLATORSCARACAS, VENEZUELA Our two South American nations have a common history of struggle against colonialism, oppression and inequality. We also share a great burden of sacrifices to create political, social and economic systems which could ensure peace, progress and prosperity for our peoples. As I was laying a wreath at the tomb of the Great Liberator this morning, I recalled his famous words in his letter from Jamaica in which he wrote: "Despite the convictions of history, South Americans have made efforts to obtain liberal, even perfect institutions, doubtless out of that instinct to aspire to the greatest possible happiness which, common to all men, is bound to follow in civil societies founded on the principles of justice, liberty and equality." These inspiring words I learnt while studying Latin American history as a student at University. It is then that I understood for the first time the great import of Simon Bolivar on the struggles and developments of the Region in which he lived and which he influenced so profoundly. His concepts of freedom, independence and justice have had pervasive effect throughout this hemisphere. His ideas and ideals deeply motivated the Father of Guyana's Independence, the late President Cheddi Jagan. The struggle of the Venezuelan people for freedom at different stages of your history have been a great inspiration to our late President and to the Guyanese people. It has given us the determination to persist and persevere because we know that the spirit of Simon Bolivar and the goodwill of the Venezuelan people will always be with the Guyanese people in our struggles for democracy and social justice.