Artocarpus Camansi (Breadnut)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bioactive Compounds in Nuts and Edible Seeds: Focusing on Brazil Nuts and Baru Almond of the Amazon and Cerrado Brazilian Biomes

Review Article SM Journal of Bioactive Compounds in Nuts and Nutrition and Edible Seeds: Focusing on Brazil Nuts Metabolism and Baru Almond of the Amazon and Cerrado Brazilian Biomes Egea MB1*, Lima DS1, Lodete AR1 and Takeuchi K1,2* 1Science and Technology, Goiano Institute of Education, Brazil 2Faculty of Nutrition, Federal University of Mato Grosso, Brazil Article Information Abstract Received date: Oct 09, 2017 The biodiversity of the Amazon and Cerrado biomes is extremely important for the populations that inhabit Accepted date: Nov 14, 2017 these areas, through the extractive collection of non-timber forest products such as fruits, nuts and edible seeds, which generate income and employment. Brazil nut (Bertholletia excelsa) is native from South America being Published date: Nov 20, 2017 found in the Amazon biome and baru almond (Dipteryx alata Vog.) is native from the Cerrado biome; these are part of the group of oleaginous that can be classified as true nuts and edible seeds, respectively. Both *Corresponding author are important sources of micronutrients that have been associated with several benefits to human health due to the presence of high levels of biologically active compounds such as minerals and vitamins. Minerals act Egea MB, Science and Technology, mostly as cofactors in various reactions, selenium has high availability in Brazil nuts and from selenocysteine Goiano Institute of Education, Brazil, and its enzymes, it exerts functions in the human body as an antioxidant, regulator of thyroid hormones and Tel: +55 64 36205636; protection of cardiovascular diseases. Among vitamins, tocopherol is a precursor to vitamin E, present in both Brazil nut and baru almond, being found in the form of α-tocopherol and having a role in the prevention of various Email: [email protected] diseases, including: cancer, diabetes, cataracts and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. -

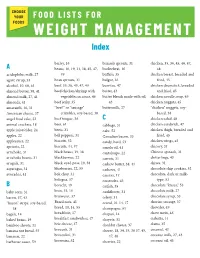

WEIGHT MANAGEMENT Index

CHOOSE YOUR FOOD LISTS FOR FOODS WEIGHT MANAGEMENT Index barley, 16 brussels sprouts, 31 chicken, 35, 36, 45, 46, 47, A beans, 10, 19, 31, 38, 45, 47, buckwheat, 16 48 acidophilus milk, 27 49 buffalo, 35 chicken breast, breaded and agave syrup, 53 bean sprouts, 31 bulgur, 16 fried, 45 alcohol, 10, 60, 61 beef, 35, 36, 45, 47, 49 burritos, 47 chicken drumstick, breaded almond butter, 38, 41 beef/chicken/shrimp with butter, 43 and fried, 45 almond milk, 27, 41 vegetables in sauce, 46 butter blends made with oil, chicken noodle soup, 49 almonds, 41 beef jerky, 35 43 chicken nuggets, 45 amaranth, 16, 31 “beef” or “sausage” buttermilk, 27 “chicken” nuggets, soy- American cheese, 37 crumbles, soy-based, 38 based, 38 angel food cake, 52 beef tongue, 36 C chicken salad, 48 animal crackers, 18 beer, 61 cabbage, 31 chicken sandwich, 47 apple juice/cider, 24 beets, 31 cake, 52 chicken thigh, breaded and apples, 22 bell peppers, 31 Canadian bacon, 35 fried, 45 applesauce, 22 biscotti, 52 candy, hard, 53 chicken wings, 45 apricots, 22 biscuits, 14, 47 canola oil, 41 chicory, 31 artichoke, 31 black beans, 19, 38 cantaloupe, 22 Chinese spinach, 31 artichoke hearts, 31 blackberries, 22 carrots, 31 chitterlings, 43 arugula, 31 black-eyed peas, 19, 38 cashew butter, 38, 41 chives, 31 asparagus, 31 blueberries, 22, 55 cashews, 41 chocolate chip cookies, 52 avocados, 41 bok choy, 31 cassava, 17 chocolate, dark or milk- bologna, 37 casseroles, 45 type, 53 B borscht, 49 catfish, 35 chocolate “kisses,” 53 baby corn, 31 bran, 15, 16 cauliflower, 31 chocolate -

Broussonetia Papyrifera Moraceae (L.) Vent

Broussonetia papyrifera (L.) Vent. Moraceae paper mulberry LOCAL NAMES Burmese (malaing); English (paper mulberry tree,paper mulberry); French (mûrier à papier,murier a papier); German (papiermaulbeerbaum); Hindi (kachnar); Indonesian (saeh); Italian (gelso papirifero del giappone,moro della China); Japanese (aka,kodzu,kename kowso,pokasa,aka kowso); Portuguese (amoreira do papel); Spanish (morera de papel); Tongan (hiapo); Trade name (paper mulberry) BOTANIC DESCRIPTION B. papyrifera is a small tree or shrub which grows naturally in Asian and Male inflorescences (Gerald D. Carr, pacific countries (Thailand, China, Myanmar, Laos, Japan, Korea). It University of Hawaii, grows to 21 m high and 70 cm dbh, with a round and spreading crown. www.forestryimages.org) The spreading, grey-brown branches, marked with stipular scars are brittle, making it susceptible to wind damage. The bark is light grey, smooth, with shallow fissures or ridges. Leaves alternate or sub-opposite, mulberry-like and papery. Some leaves are distinctly deep lobed, while others are un-lobed and several different shapes of leaves may appear on the same shoot. Petioles are 3-10 cm long while stipules are 1.6-2.0 cm long. Male flower 3.5-7.5 cm long, yellowish-white, with pendulous catkin-like spikes; perianth campanulate, hairy, 4-fid, and its segments are valvate. Habit at Keanae Arboretum Maui, Hawaii (Forest & Kim Starr) Female flowers in rounded clusters, globose pedunculate heads about 1.3 cm in diameter; persistent, hairy, clavate bracts subtend flowers. Fruit shiny-reddish, fleshy, globose and compound with the achenes 1-2 cm long and wide hanging on long fleshy stalks. -

Fats Ebook Feb 02.Pdf

2 DRHYMAN.COM Contents Contents INTRODUCTION ................................. 8 PART I ........................................... 11 Dietary Fats: The Good, Bad and the Ugly ............................................ 11 Fatty Acids ............................................................................................ 11 Saturated Fat ........................................................................................ 12 Polyunsaturated Fats ............................................................................ 14 Essential Fatty Acids 101- Omega-3 and Omega-6 ............................... 14 The Beneficial Omega-6 Fatty Acid: GLA ............................................... 16 How Fatty Acids Affect Brain Health ..................................................... 17 Omega-7 Fatty Acids ............................................................................ 18 Monounsaturated Fat ............................................................................ 18 Trans Fats ............................................................................................. 20 Trans Fats and Health ........................................................................... 21 Toxins in Fat .......................................................................................... 22 A Case for Organic ................................................................................ 23 DRHYMAN.COM 3 PART II .......................................... 24 Animal Fats ....................................................................... -

Polynesian Canoe Plants, Including Breadfruit, Taro, and Coconut: the Ultimate in Sustainability Planning Posted on June 27, 2019 by Leslie Lang

HOME HOURS & DIRECTIONS GARDEN SLIDESHOW GARDEN NEWS & BLOG Polynesian Canoe Plants, Including Breadfruit, Taro, and Coconut: the Ultimate in Sustainability Planning Posted on June 27, 2019 by Leslie Lang Do you know about “canoe plants?” These are the plants—such as kalo (taro), ‘ulu (breadfruit), and niu (coconut), among others—that Polynesians brought in their carefully-stocked voyaging canoes perhaps 1,600 years ago when they first settled in Hawai‘i. Canoe plants are one more piece of the evidence showing us that the people who colonized Hawai‘i were intelligent voyagers who came in planned expeditions, not islanders who drifted here unintentionally. Not only did they successfully navigate the oceans like highways, but before they left home to explore and settle new lands, they prepared themselves well. After all, they had to sustain themselves both during their long journeys and also upon arrival in a new island group, where they didn’t know what resources they would find. They maximized their limited space by packing seeds, roots, shoots, and cuttings of their most critical plants, the ones they relied on the most for food, medicine, and for making containers, fabric, cordage, and more. We can identify about 24 plants that arrived in Hawai‘i as canoe plants. You can see samples of some of them at Hawaii Tropical Botanical Garden. The Most Significant Polynesian Canoe Plants: ‘Ulu ‘Ulu (Artocarpus altilis, Artocarpus incisus or Artocarpus communis) belongs to the Moracceae (fig or mulberry) family. Known in English as breadfruit, the ‘ulu tree produces a “fruit” that is actually a vegetable with a high carbohydrate content. -

Breadfruit, Breadnut, and Jackfruit: How Are They Related? by Fred Prescod

Comparing Breadfruit, Breadnut, and Jackfruit: How are they Related? by Fred Prescod In the first article we traced the arrival of the breadfruit plant into the New World. Now we compare breadfruit with its close relatives, breadnut and jackfruit, both also found in St. Vincent and the Grenadines. These three plants all belong to the botanical genus known as Artocarpus. The name Artocarpus is applied to about 60 different trees, all members of the fig or mulberry family (Moraceae), a botanical division which at one time included Cannabis. Trees of this genus are native to Southeast Asia and the Pacific region. The generic name (Artocarpus) is derived from the Greek words ‘artos’ (meaning bread) and ‘karpos’ (meaning fruit). The name is thought to have been established by Johann Reinhold Forster and J. Georg Adam Forster, botanists aboard the HMS Resolution on James Cook’s second voyage. In J.W. Pursglove’s publication on tropical crops, he reports that Joseph Banks, James Cook and other early travelers brought back descriptions of the breadfruit plant using phrases such as ‘bread itself is gathered as a fruit’. Breadfruit tree – Calliaqua, St. Vincent Breadfruit tree at Calliaqua, St. Vincent. [Photo by Jim Lounsberry] Unfortunately some confusion often arises from the use of common names, where a single common name may be applied to different plants in different areas. Nevertheless breadfruit itself is recognized as a seedless form of the plant known botanically as Artocarpus altilis (also Artocarpus communis), while breadnut (often also listed as Artocarpus altilis) was originally thought to be simply a race or form of the same plant with fruits containing seeds. -

Chapter 1 Definitions and Classifications for Fruit and Vegetables

Chapter 1 Definitions and classifications for fruit and vegetables In the broadest sense, the botani- Botanical and culinary cal term vegetable refers to any plant, definitions edible or not, including trees, bushes, vines and vascular plants, and Botanical definitions distinguishes plant material from ani- Broadly, the botanical term fruit refers mal material and from inorganic to the mature ovary of a plant, matter. There are two slightly different including its seeds, covering and botanical definitions for the term any closely connected tissue, without vegetable as it relates to food. any consideration of whether these According to one, a vegetable is a are edible. As related to food, the plant cultivated for its edible part(s); IT botanical term fruit refers to the edible M according to the other, a vegetable is part of a plant that consists of the the edible part(s) of a plant, such as seeds and surrounding tissues. This the stems and stalk (celery), root includes fleshy fruits (such as blue- (carrot), tuber (potato), bulb (onion), berries, cantaloupe, poach, pumpkin, leaves (spinach, lettuce), flower (globe tomato) and dry fruits, where the artichoke), fruit (apple, cucumber, ripened ovary wall becomes papery, pumpkin, strawberries, tomato) or leathery, or woody as with cereal seeds (beans, peas). The latter grains, pulses (mature beans and definition includes fruits as a subset of peas) and nuts. vegetables. Definition of fruit and vegetables applicable in epidemiological studies, Fruit and vegetables Edible plant foods excluding -

Good Things Happen When You Plant Trees

Plant a Tree … … and Good Things Happen! A guideline for younger children By Mary McLaughlin & Judy Osgood Illustrations by Edward Brooks Plant a tree and good things happen . 1. To the air we breathe 2. To the food we eat 3. To the birds that fly 4. To the animals that live on the ground 5. To the rivers, the ponds and the sea 6. To the jobs we can do 7. To the joy we have in play Teaching guide on trees. Created by Mary McLaughlin & Judy Osgood. Plant a tree and good things happen . to the air we breathe How do trees help us breathe? Key Concepts: Trees are the lungs of the earth. People need to breathe in air with oxygen to live. People breathe in oxygen (O2) and breath out carbon dioxide (CO2). Trees take in carbon dioxide and turn it into oxygen. Questions and Activities: *Put your hand on your chest. Breathe in and out. Do you feel the air coming in and going out? Where does the air come into the body and where does it exit? What organ of the body holds the air? What do we mean by bad or dirty air? *If you breathed in bad air what would happen to you? What causes bad air? What helps the air to improve? What are the other gases that make up the air that we breath? 1 Plant a tree and good things happen . to the food we eat Name some trees that give you food to eat: Brainstorm: things we eat that grow on trees: Ackee Limes Allspice Mango Almonds Maple syrup Apples Moringa Bananas Naseberry Bay leaves Olives Beechnuts Oranges Brazil nuts Pawpaw Breadfruit Peaches Cashews Persimmon Cherries Pigeon pea Chestnuts Pine nuts Cinnamon Pistachios Cloves Plums Cocoa Pomegranate Coconuts Soursop Questions and Activities Dates Starfruit *How many of these have you eaten? Gingko nuts Tamarind *Can you identify the smell and taste? Guava Walnuts *Categorize what you’ve brainstormed. -

The Castilleae, a Tribe of the Moraceae, Renamed and Redefined Due to the Exclusion of the Type Genus Olmedia From

Bot. Neerl. Ada 26(1), February 1977, p. 73-82, The Castilleae, a tribe of the Moraceae, renamed and redefined due to the exclusion of the type genus Olmedia from the “Olmedieae” C.C. Berg Instituut voor Systematische Plantkunde, Utrecht SUMMARY New data on in the of Moraceae which known cladoptosis group was up to now as the tribe Olmedieae led to a reconsideration ofthe position ofOlmedia, and Antiaropsis , Sparattosyce. The remainder ofthe tribe is redefined and is named Castilleae. 1. INTRODUCTION The monotypic genus Olmedia occupies an isolated position within the neo- tropical Olmedieae. Its staminate flowers have valvate tepals, inflexed stamens springing back elastically at anthesis, and sometimes well-developed pistil- lodes. Current anatomical research on the wood of Moraceae (by Dr. A. M. W. Mennega) and recent field studies (by the present author) revealed that Olmedia is also distinct in anatomical characters of the wood and because of the lack of self-pruning branches. These differences between Olmedia and the other representatives of the tribe demand for reconsideration of the position of the genus and the deliminationof the tribe. The Olmedia described The genus was by Ruiz & Pavon (1794). original description mentioned that the stamens bend outward elastically at anthesis. Nevertheless it was placed in the “Artocarpeae” (cf. Endlicher 1836-1840; Trecul 1847), whereas it should have been placed in the “Moreae” on ac- of of count the characters the stamens which were rather exclusively used for separating the two taxa. Remarkably Trecul (1847) in his careful study on the “Artocarpeae” disregarded the (described) features of the stamens. -

Bengal Slow Loris from Madhupur National Park, Bangladesh

47 Asian Primates Journal 9(1), 2021 EXTIRPATED OR IGNORED? FIRST EVIDENCE OF BENGAL SLOW LORIS Nycticebus bengalensis FROM MADHUPUR NATIONAL PARK, BANGLADESH Tanvir Ahmed1* and Md Abdur Rahman Rupom2 1 Wildlife Research and Conservation Unit, Nature Conservation Management (NACOM), Dhaka 1212, Bangladesh. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Holding No. 1230, Masterpara, Madhupur 1996, Tangail, Dhaka, Bangladesh. E-mail: [email protected] * Corresponding author ABSTRACT We report the first verifiable record of globally Endangered Bengal Slow LorisNycticebus bengalensis in Madhupur National Park, an old-growth natural Sal Shorea robusta forest in north-central Bangladesh. On 21 October 2020, we sighted a male N. bengalensis in Madhupur National Park by chance while recording videos on the forest’s biodiversity. For three decades, N. bengalensis was believed to have been extirpated from the Sal forests in Bangladesh, in the absence of a specialized nocturnal survey. Given the alarming state of extreme habitat alterations due to human activities and other threats to N. bengalensis in Bangladesh, an assessment of its distribution and population status in Sal forests is crucial for conservation planning. Keywords: Distribution, Nycticebus bengalensis, slow loris, strepsirrhine, tropical moist deciduous forest Bengal Slow Loris Nycticebus bengalensis author encountered an adult male N. bengalensis in (Lacépède) is an arboreal strepsirrhine primate native a roadside bamboo Bambusa sp. clump near Lohoria to Bangladesh, north-eastern India, Bhutan, Myanmar, Deer Breeding Centre at Lohoria Beat (24°41’44.7”N, China, Thailand, Cambodia, Lao PDR and Viet Nam 90°06’21.1”E; Fig. 2). A group of Macaca mulatta (Nekaris et al., 2020). -

Biogeography, Phylogeny and Divergence Date Estimates of Artocarpus (Moraceae)

Annals of Botany 119: 611–627, 2017 doi:10.1093/aob/mcw249, available online at www.aob.oxfordjournals.org Out of Borneo: biogeography, phylogeny and divergence date estimates of Artocarpus (Moraceae) Evelyn W. Williams1,*, Elliot M. Gardner1,2, Robert Harris III2,†, Arunrat Chaveerach3, Joan T. Pereira4 and Nyree J. C. Zerega1,2,* 1Chicago Botanic Garden, Plant Science and Conservation, 1000 Lake Cook Road, Glencoe, IL 60022, USA, 2Northwestern University, Plant Biology and Conservation Program, 2205 Tech Dr., Evanston, IL 60208, USA, 3Faculty of Science, Genetics Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/aob/article/119/4/611/2884288 by guest on 03 January 2021 and Environmental Toxicology Research Group, Khon Kaen University, 123 Mittraphap Highway, Khon Kaen, 40002, Thailand and 4Forest Research Centre, Sabah Forestry Department, PO Box 407, 90715 Sandakan, Sabah, Malaysia *For correspondence. E-mail [email protected], [email protected] †Present address: Carleton College, Biology Department, One North College St., Northfield, MN 55057, USA. Received: 25 March 2016 Returned for revision: 1 August 2016 Editorial decision: 3 November 2016 Published electronically: 10 January 2017 Background and Aims The breadfruit genus (Artocarpus, Moraceae) includes valuable underutilized fruit tree crops with a centre of diversity in Southeast Asia. It belongs to the monophyletic tribe Artocarpeae, whose only other members include two small neotropical genera. This study aimed to reconstruct the phylogeny, estimate diver- gence dates and infer ancestral ranges of Artocarpeae, especially Artocarpus, to better understand spatial and tem- poral evolutionary relationships and dispersal patterns in a geologically complex region. Methods To investigate the phylogeny and biogeography of Artocarpeae, this study used Bayesian and maximum likelihood approaches to analyze DNA sequences from six plastid and two nuclear regions from 75% of Artocarpus species, both neotropical Artocarpeae genera, and members of all other Moraceae tribes. -

Artocarpus Heterophyllus Lam

A Artocarpus heterophyllus Lam. M.K. HOSSAIN and T.K. NATH Institute of Forestry and Environmental Sciences Chittagong University, Bangladesh MORACEAE (MULBERRY FAMILY) Artocarpus philippensis, A. brasilliensis, A. maxima Apushpa, ashaya, banun, chakki, champa, herali, jack, jackfruit, kanthal, khanon, khnor, kos, langka, makmi, miij, miijhnang, mit, nangka, pagal, pala, palasu, palavu, panas, panasa, panasam, peignai, pila, waraka, wela (Alam and others 1985, Brandis 1906, Gamble 1922, Gunasena 1993, Jensen 1995) Artocarpus heterophyllus is the most widespread species of the many ways superior to teak (Tectona grandis) (Howard 1951). genus. It forms forest associations with homesteads (Leuschn- However, its strength is 75 to 80 percent that of teak (Wealth er and Khaleque 1987, Topark-Ngarm 1990), tropical rain of India 1985). Roots of old trees are greatly prized for wood forests, dry evergreen forests, and the montane vegetation of carving and picture framing (Morton 1965). Though heart- mountain groups (Gunasena 1993). Artocarpus heterophyllus wood is resistant to borer and termite attack, sapwood is high- grows in the evergreen forests of the western hills of India, Sri ly susceptible to borer attack and perishes easily. Penetration Lanka, and the Deccan plain of Bangladesh (Alam and others of preservative is difficult but the wood seasons quickly. The 1985, Chopra and others 1963). It is normally found in associ- fruit of A. heterophyllus is popular among the rural people of ation with permanent human settlement throughout the Indi- the Indian subcontinent. It enjoys special favor in some home an subcontinent, Bangladesh, the coast of east Africa, Myan- gardens because it has numerous culinary uses and is abundant mar, northern Brazil, Jamaica, and Surinam (Alam and others during the heavy monsoon rains.