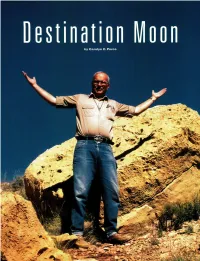

Eugene M. Shoemaker 1928-1997

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SPECIAL Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 Collides with Jupiter

SL-9/JUPITER ENCOUNTER - SPECIAL Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 Collides with Jupiter THE CONTINUATION OF A UNIQUE EXPERIENCE R.M. WEST, ESO-Garching After the Storm Six Hectic Days in July eration during the first nights and, as in other places, an extremely rich data The recent demise of comet Shoe ESO was but one of many profes material was secured. It quickly became maker-Levy 9, for simplicity often re sional observatories where observations evident that infrared observations, es ferred to as "SL-9", was indeed spectac had been planned long before the critical pecially imaging with the far-IR instru ular. The dramatic collision of its many period of the "SL-9" event, July 16-22, ment TIMMI at the 3.6-metre telescope, fragments with the giant planet Jupiter 1994. It is now clear that practically all were perfectly feasible also during day during six hectic days in July 1994 will major observatories in the world were in time, and in the end more than 120,000 pass into the annals of astronomy as volved in some way, via their telescopes, images were obtained with this facility. one of the most incredible events ever their scientists or both. The only excep The programmes at most of the other predicted and witnessed by members of tions may have been a few observing La Silla telescopes were also successful, this profession. And never before has a sites at the northernmost latitudes where and many more Gigabytes of data were remote astronomical event been so ac the bright summer nights and the very recorded with them. -

Cross-References ASTEROID IMPACT Definition and Introduction History of Impact Cratering Studies

18 ASTEROID IMPACT Tedesco, E. F., Noah, P. V., Noah, M., and Price, S. D., 2002. The identification and confirmation of impact structures on supplemental IRAS minor planet survey. The Astronomical Earth were developed: (a) crater morphology, (b) geo- 123 – Journal, , 1056 1085. physical anomalies, (c) evidence for shock metamor- Tholen, D. J., and Barucci, M. A., 1989. Asteroid taxonomy. In Binzel, R. P., Gehrels, T., and Matthews, M. S. (eds.), phism, and (d) the presence of meteorites or geochemical Asteroids II. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, pp. 298–315. evidence for traces of the meteoritic projectile – of which Yeomans, D., and Baalke, R., 2009. Near Earth Object Program. only (c) and (d) can provide confirming evidence. Remote Available from World Wide Web: http://neo.jpl.nasa.gov/ sensing, including morphological observations, as well programs. as geophysical studies, cannot provide confirming evi- dence – which requires the study of actual rock samples. Cross-references Impacts influenced the geological and biological evolu- tion of our own planet; the best known example is the link Albedo between the 200-km-diameter Chicxulub impact structure Asteroid Impact Asteroid Impact Mitigation in Mexico and the Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary. Under- Asteroid Impact Prediction standing impact structures, their formation processes, Torino Scale and their consequences should be of interest not only to Earth and planetary scientists, but also to society in general. ASTEROID IMPACT History of impact cratering studies In the geological sciences, it has only recently been recog- Christian Koeberl nized how important the process of impact cratering is on Natural History Museum, Vienna, Austria a planetary scale. -

Destination Moon

Ill ".=\'.\, . : t.\ i...ii. 4'i.' --- v 1, 2*..- e> . 1.... ...*f. - .. .. .../C-'.»i.:5.1:• \ I: .. ...: ... ':4r-... - i.. ·.· I . I ·#. - I, :P.k 0 1 '. -1-3:Z:,ile<52.4 -2. .3••••4 - ....., 1 - I ..... 3/4 I <:.9, . /•/f••94*/ ,,iS· .... I ... ....... 9492./i- ..·,61« 4/.th_ r-*- .. -I,r * 116.-452*:••:il-.--•• . .....a• 1 --, •.11:E I . ".59/.-R:&6.Aidillizatu:ill'Illrclilllll 9 St" "' 4.... ... 'Ablf*liE•*.0/8/49/18•09#J'£• .-t-i «, ...' '-t ---- ·· -.t-:.:.'• --,•1*4*14-=..»r,3.hk= 4-lk/ *7·· •-,·:s - '' 21:1 . -0.6..ts-9....4559*"4914*Em'6rt'" .. « 036 ·.. '.... ..'·2&4:i•#+,M/ri:.1*-%,TYRf/036B.e... - ....2:'. .. *... '. '!..i. '':3..i-,f....35"ti F:Y.'..t•: &.....:. 39•'.•........ - ..., ..7. .- P 036.1..' -.Zi - , 93327 . « tr. 1 '. .- I . '.. I ... .'... 'SS> <13· '9•25 ."'t-·,·:·- " :· •t :Ali.•'.'; • - 'r ...• r..... ' ... .... .. " .4 4 ..2- -.*.. 3. .. : , _sry»5433.5.,+· i<29*643, W5• ./'..'r· -. 4-··./.-i--fR...1-L...'.te....bkir.i<Ativi•haRN,1.254i'*"*61»4-=•• 6.... 61 . 31 /'- 5 301... ....•L . , . - - . '2.1 . ' -' »4 /2/323#9/44 ZEIII:ill)*lill//Il/6,1-'.cri:rre I. p ·: , 4 ·,.3*4,·to.4.-•44 4 .,I-tS••7•,<•.•·:L,4..'::....,i... ..I·."i271/Ve;*m#6:d 54.... .. -,•....- . I..,418'I.,4I.,•....6..#i r:'.,:•St»1.·:·'7· ···- . t'-.,jit- 1-6#.19.-'*-. ' -e - .c, .•.. C'!•-042,.-• .... -I ./- =r- . 2 2. -" ' .t. · '., -042,,. ' '/.9. •SS ..2.. 11•11•»..••...qwGILLET+*frs'.. :. " . .... I .- , .. - ....,.k.... -< 3.5*«· ·: . ' i.1., li-, f 20- PR :21 . 0• . c. .Fh: ---, 1.4':. '•,. -,-t.Z:ft,•• •'r,4.4, 4 r • . -

Special Catalogue Milestones of Lunar Mapping and Photography Four Centuries of Selenography on the Occasion of the 50Th Anniversary of Apollo 11 Moon Landing

Special Catalogue Milestones of Lunar Mapping and Photography Four Centuries of Selenography On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11 moon landing Please note: A specific item in this catalogue may be sold or is on hold if the provided link to our online inventory (by clicking on the blue-highlighted author name) doesn't work! Milestones of Science Books phone +49 (0) 177 – 2 41 0006 www.milestone-books.de [email protected] Member of ILAB and VDA Catalogue 07-2019 Copyright © 2019 Milestones of Science Books. All rights reserved Page 2 of 71 Authors in Chronological Order Author Year No. Author Year No. BIRT, William 1869 7 SCHEINER, Christoph 1614 72 PROCTOR, Richard 1873 66 WILKINS, John 1640 87 NASMYTH, James 1874 58, 59, 60, 61 SCHYRLEUS DE RHEITA, Anton 1645 77 NEISON, Edmund 1876 62, 63 HEVELIUS, Johannes 1647 29 LOHRMANN, Wilhelm 1878 42, 43, 44 RICCIOLI, Giambattista 1651 67 SCHMIDT, Johann 1878 75 GALILEI, Galileo 1653 22 WEINEK, Ladislaus 1885 84 KIRCHER, Athanasius 1660 31 PRINZ, Wilhelm 1894 65 CHERUBIN D'ORLEANS, Capuchin 1671 8 ELGER, Thomas Gwyn 1895 15 EIMMART, Georg Christoph 1696 14 FAUTH, Philipp 1895 17 KEILL, John 1718 30 KRIEGER, Johann 1898 33 BIANCHINI, Francesco 1728 6 LOEWY, Maurice 1899 39, 40 DOPPELMAYR, Johann Gabriel 1730 11 FRANZ, Julius Heinrich 1901 21 MAUPERTUIS, Pierre Louis 1741 50 PICKERING, William 1904 64 WOLFF, Christian von 1747 88 FAUTH, Philipp 1907 18 CLAIRAUT, Alexis-Claude 1765 9 GOODACRE, Walter 1910 23 MAYER, Johann Tobias 1770 51 KRIEGER, Johann 1912 34 SAVOY, Gaspare 1770 71 LE MORVAN, Charles 1914 37 EULER, Leonhard 1772 16 WEGENER, Alfred 1921 83 MAYER, Johann Tobias 1775 52 GOODACRE, Walter 1931 24 SCHRÖTER, Johann Hieronymus 1791 76 FAUTH, Philipp 1932 19 GRUITHUISEN, Franz von Paula 1825 25 WILKINS, Hugh Percy 1937 86 LOHRMANN, Wilhelm Gotthelf 1824 41 USSR ACADEMY 1959 1 BEER, Wilhelm 1834 4 ARTHUR, David 1960 3 BEER, Wilhelm 1837 5 HACKMAN, Robert 1960 27 MÄDLER, Johann Heinrich 1837 49 KUIPER Gerard P. -

Planning a Mission to the Lunar South Pole

Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter: (Diviner) Audience Planning a Mission to Grades 9-10 the Lunar South Pole Time Recommended 1-2 hours AAAS STANDARDS Learning Objectives: • 12A/H1: Exhibit traits such as curiosity, honesty, open- • Learn about recent discoveries in lunar science. ness, and skepticism when making investigations, and value those traits in others. • Deduce information from various sources of scientific data. • 12E/H4: Insist that the key assumptions and reasoning in • Use critical thinking to compare and evaluate different datasets. any argument—whether one’s own or that of others—be • Participate in team-based decision-making. made explicit; analyze the arguments for flawed assump- • Use logical arguments and supporting information to justify decisions. tions, flawed reasoning, or both; and be critical of the claims if any flaws in the argument are found. • 4A/H3: Increasingly sophisticated technology is used Preparation: to learn about the universe. Visual, radio, and X-ray See teacher procedure for any details. telescopes collect information from across the entire spectrum of electromagnetic waves; computers handle Background Information: data and complicated computations to interpret them; space probes send back data and materials from The Moon’s surface thermal environment is among the most extreme of any remote parts of the solar system; and accelerators give planetary body in the solar system. With no atmosphere to store heat or filter subatomic particles energies that simulate conditions in the Sun’s radiation, midday temperatures on the Moon’s surface can reach the stars and in the early history of the universe before 127°C (hotter than boiling water) whereas at night they can fall as low as stars formed. -

March 21–25, 2016

FORTY-SEVENTH LUNAR AND PLANETARY SCIENCE CONFERENCE PROGRAM OF TECHNICAL SESSIONS MARCH 21–25, 2016 The Woodlands Waterway Marriott Hotel and Convention Center The Woodlands, Texas INSTITUTIONAL SUPPORT Universities Space Research Association Lunar and Planetary Institute National Aeronautics and Space Administration CONFERENCE CO-CHAIRS Stephen Mackwell, Lunar and Planetary Institute Eileen Stansbery, NASA Johnson Space Center PROGRAM COMMITTEE CHAIRS David Draper, NASA Johnson Space Center Walter Kiefer, Lunar and Planetary Institute PROGRAM COMMITTEE P. Doug Archer, NASA Johnson Space Center Nicolas LeCorvec, Lunar and Planetary Institute Katherine Bermingham, University of Maryland Yo Matsubara, Smithsonian Institute Janice Bishop, SETI and NASA Ames Research Center Francis McCubbin, NASA Johnson Space Center Jeremy Boyce, University of California, Los Angeles Andrew Needham, Carnegie Institution of Washington Lisa Danielson, NASA Johnson Space Center Lan-Anh Nguyen, NASA Johnson Space Center Deepak Dhingra, University of Idaho Paul Niles, NASA Johnson Space Center Stephen Elardo, Carnegie Institution of Washington Dorothy Oehler, NASA Johnson Space Center Marc Fries, NASA Johnson Space Center D. Alex Patthoff, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Cyrena Goodrich, Lunar and Planetary Institute Elizabeth Rampe, Aerodyne Industries, Jacobs JETS at John Gruener, NASA Johnson Space Center NASA Johnson Space Center Justin Hagerty, U.S. Geological Survey Carol Raymond, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Lindsay Hays, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Paul Schenk, -

DMAAC – February 1973

LUNAR TOPOGRAPHIC ORTHOPHOTOMAP (LTO) AND LUNAR ORTHOPHOTMAP (LO) SERIES (Published by DMATC) Lunar Topographic Orthophotmaps and Lunar Orthophotomaps Scale: 1:250,000 Projection: Transverse Mercator Sheet Size: 25.5”x 26.5” The Lunar Topographic Orthophotmaps and Lunar Orthophotomaps Series are the first comprehensive and continuous mapping to be accomplished from Apollo Mission 15-17 mapping photographs. This series is also the first major effort to apply recent advances in orthophotography to lunar mapping. Presently developed maps of this series were designed to support initial lunar scientific investigations primarily employing results of Apollo Mission 15-17 data. Individual maps of this series cover 4 degrees of lunar latitude and 5 degrees of lunar longitude consisting of 1/16 of the area of a 1:1,000,000 scale Lunar Astronautical Chart (LAC) (Section 4.2.1). Their apha-numeric identification (example – LTO38B1) consists of the designator LTO for topographic orthophoto editions or LO for orthophoto editions followed by the LAC number in which they fall, followed by an A, B, C or D designator defining the pertinent LAC quadrant and a 1, 2, 3, or 4 designator defining the specific sub-quadrant actually covered. The following designation (250) identifies the sheets as being at 1:250,000 scale. The LTO editions display 100-meter contours, 50-meter supplemental contours and spot elevations in a red overprint to the base, which is lithographed in black and white. LO editions are identical except that all relief information is omitted and selenographic graticule is restricted to border ticks, presenting an umencumbered view of lunar features imaged by the photographic base. -

The Scientific Method an Investigation of Impact Craters

National Aeronautics and Space Administration The Scientific Method: An Investigation of Impact Craters Recommended for Grades 5,6,7 www.nasa.gov Table of Contents Digital Learning Network (DLN) .................................................................................................... 3 Overview................................................................................................................................................. 3 National Standards............................................................................................................................. 4 Sequence of Events........................................................................................................................... 5 Videoconference Outline ................................................................................................................. 6 Videoconference Event .................................................................................................................... 7 Vocabulary...........................................................................................................................................10 Videoconference Guidelines........................................................................................................11 Pre- and Post-Assessment ...........................................................................................................12 Post-Conference Activity...............................................................................................................14 -

19. Near-Earth Objects Chelyabinsk Meteor: 2013 ~0.5 Megaton Airburst ~1500 People Injured

Astronomy 241: Foundations of Astrophysics I 19. Near-Earth Objects Chelyabinsk Meteor: 2013 ~0.5 megaton airburst ~1500 people injured (C) Don Davis Asteroids 101 — B612 Foundation Great Daylight Fireball: 1972 Earthgrazer: The Great Daylight Fireball of 1972 Tunguska Meteor: 1908 Asteroid or comet: D ~ 40 m ~10 megaton airburst ~40 km destruction radius The Tunguska Impact Tunguska: The Largest Recent Impact Event Barringer Crater: ~50 ky BP M-type asteroid: D ~ 50 m ~10 megaton impact 1.2 km crater diameter Meteor Crater — Wikipedia Chicxulub Crater: ~65 My BP Asteroid: D ~ 10 km 180 km crater diameter Chicxulub Crater— Wikipedia Comets and Meteor Showers Comets shed dust and debris which slowly spread out as they move along the comet’s orbit. If the Earth encounters one of these trails, we get a Breakup of a Comet meteor shower. Meteor Stream Perseid Meteor Shower Raining Perseids Major Meteor Showers Forty Thousand Meteor Origins Across the Sky Known Potentially-Hazardous Objects Near-Earth object — Wikipedia Near-Earth object — Wikipedia Origin of Near-Earth Objects (NEOs) ! WHAM Mars Some fragments wind up on orbits which are resonant with Jupiter. Their orbits grow more elliptical, finally entering the inner solar system. Wikipedia: Asteroid belt Asteroid Families Many asteroids are members of families; they have similar orbits and compositions (indicated by colors). Asteroid Belt Populations Inner belt asteroids (left) and families (right). Origin of Key Stages in the Evolution of the Asteroid Vesta Processed Family Members Crust Surface Magnesium-Sliicate Lavas Meteorites Mantle (Olivine) Iron-Nickle Core Stony Irons? As smaller bodies in the early Solar System Heavier elements sink to the Occasional impacts with other bodies fall together, the asteroid agglomerates. -

The Tennessee Meteorite Impact Sites and Changing Perspectives on Impact Cratering

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN QUEENSLAND THE TENNESSEE METEORITE IMPACT SITES AND CHANGING PERSPECTIVES ON IMPACT CRATERING A dissertation submitted by Janaruth Harling Ford B.A. Cum Laude (Vanderbilt University), M. Astron. (University of Western Sydney) For the award of Doctor of Philosophy 2015 ABSTRACT Terrestrial impact structures offer astronomers and geologists opportunities to study the impact cratering process. Tennessee has four structures of interest. Information gained over the last century and a half concerning these sites is scattered throughout astronomical, geological and other specialized scientific journals, books, and literature, some of which are elusive. Gathering and compiling this widely- spread information into one historical document benefits the scientific community in general. The Wells Creek Structure is a proven impact site, and has been referred to as the ‘syntype’ cryptoexplosion structure for the United State. It was the first impact structure in the United States in which shatter cones were identified and was probably the subject of the first detailed geological report on a cryptoexplosive structure in the United States. The Wells Creek Structure displays bilateral symmetry, and three smaller ‘craters’ lie to the north of the main Wells Creek structure along its axis of symmetry. The question remains as to whether or not these structures have a common origin with the Wells Creek structure. The Flynn Creek Structure, another proven impact site, was first mentioned as a site of disturbance in Safford’s 1869 report on the geology of Tennessee. It has been noted as the terrestrial feature that bears the closest resemblance to a typical lunar crater, even though it is the probable result of a shallow marine impact. -

Rocks, Soils and Surfaces: Teacher Guide

National Aeronautics and Space Administration ROCKS, SOILS, AND SURFACES Planetary Sample and Impact Cratering Unit Teacher Guide Goal: This activity is designed to introduce students to rocks, “soils”, and surfaces on planetary worlds, through the exploration of lunar samples collected by Apollo astronauts and the study of the most dominant geologic process across the Solar System, the impact process. Students will gain an understanding of how the study of collected samples and impact craters can help improve our understanding of the history of the Moon, Earth, and our Solar System. Additionally, this activity will enable students to gain experience with scientific practices and the nature of science as they model skills and practices used by professional scientists. Objectives: Students will: 1. Make observations of rocks, “soil”, and surface features 2. Gain background information on rocks, “soil”, and surface features on Earth and the Moon 3. Apply background knowledge related to rocks, soils, and surfaces on Earth toward gaining a better understanding of these aspects of the Moon. This includes having students: a. Identify common lunar surface features b. Create a model lunar surface c. Identify the three classifications of lunar rocks d. Simulate the development of lunar regolith e. Identify the causes and formation of impact craters 4. Design and conduct an experiment on impact craters 5. Create a plan to investigate craters on Earth and on the Moon 6. Gain an understanding of the nature of science and scientific practices by: a. Making initial observations b. Asking preliminary questions c. Applying background knowledge d. Displaying data e. Analyzing and interpreting data Grade Level: 6 – 8* *Grade Level Adaptations: This activity can also be used with students in grades 5 and 9-12. -

Nördlingen 2010: the Ries Crater, the Moon, and the Future of Human Space Exploration, P

Program and Abstract Volume LPI Contribution No. 1559 The Ries Crater, the Moon, and the Future of Human Space Exploration June 25–27, 2010 Nördlingen, Germany Sponsors Museum für Naturkunde – Leibniz-Institute for Research on Evolution and Biodiversity at the Humboldt University Berlin, Germany Institut für Planetologie, University of Münster, Germany Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt DLR (German Aerospace Center) at Berlin, Germany Institute of Geoscience, University of Freiburg, Germany Lunar and Planetary Institute (LPI), Houston, USA Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (German Science Foundation), Bonn, Germany Barringer Crater Company, Decatur, USA Meteoritical Society, USA City of Nördlingen, Germany Ries Crater Museum, Nördlingen, Germany Community of Otting, Ries, Germany Märker Cement Factory, Harburg, Germany Local Organization City of Nördlingen Museum für Naturkunde – Leibniz- Institute for Research on Evolution and Biodiversity at the Humboldt University Berlin Ries Crater Museum, Nördlingen Center of Ries Crater and Impact Research (ZERIN), Nördlingen Society Friends of the Ries Crater Museum, Nördlingen Community of Otting, Ries Märker Cement Factory, Harburg Organizing and Program Committee Prof. Dieter Stöffler, Museum für Naturkunde, Berlin Prof. Wolf Uwe Reimold, Museum für Naturkunde, Berlin Dr. Kai Wünnemann, Museum für Naturkunde, Berlin Hermann Faul, First Major of Nördlingen Prof. Thomas Kenkmann, Freiburg Prof. Harald Hiesinger, Münster Prof. Tilman Spohn, DLR, Berlin Dr. Ulrich Köhler, DLR, Berlin Dr. David Kring, LPI, Houston Dr. Axel Wittmann, LPI, Houston Gisela Pösges, Ries Crater Museum, Nördlingen Ralf Barfeld, Chair, Society Friends of the Ries Crater Museum Lunar and Planetary Institute LPI Contribution No. 1559 Compiled in 2010 by LUNAR AND PLANETARY INSTITUTE The Lunar and Planetary Institute is operated by the Universities Space Research Association under a cooperative agreement with the Science Mission Directorate of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.