C:\Users\Petermenell\Desktop\RCLA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Remix Survey 7-6-2010-2

Remix Culture Survey Instrument Which of the following do you currently own? (check all that apply) • High-definition television set • DVD Player • Personal Video Recorder (e.g. TiVo) • Cable/Satellite television connection • Video Game console (e.g. XBOX, PlayStation) • Portable video game device (e.g. Nintendo DS, PSP) • High-speed internet connection (e.g. DSL, cable modem) • Stereo system or portable CD player • Portable MP3 player (e.g. iPod) • Satellite radio (XM, Sirius) • Turntables • Video camera • E-book reader (e.g. Kindle) • Tablet computer (e.g. iPad) • Smartphone (e.g. iPhone, Blackberry, Droid) • A non-smartphone mobile phone (phone calls and text but doesn’t have more advanced features like video and web) How often have you done the following activities in the past month? Never Rarely Sometimes Often Daily or more • Watched TV shows or movies on a TV set (not computer) • Played non-online games on a console (e.g. XBOX, PlayStation) • Played non-online games on a computer • Listened to CDs • Listened to digital music (e.g. MP3s) • Listened to the radio • Read books • Read newspapers or magazines • Download or streamed a movie, television show, or video clip online. • Played a game online • Downloaded or streamed music online For the remainder of this survey, please consider the following definitions: Sample-based media: Creating something different using elements of preexisting media (pieces of music, games, shows, video, text, or photos). There are two specific subgenres of sample based media: • Remix: Adding, taking out, mixing, combining or editing your own elements or effects with preexisting media (e.g. film, music, video games) to produce something different • Mash-up: Combining only elements of preexisting media together (e.g. -

The Effects of Digital Music Distribution" (2012)

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Research Papers Graduate School Spring 4-5-2012 The ffecE ts of Digital Music Distribution Rama A. Dechsakda [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp The er search paper was a study of how digital music distribution has affected the music industry by researching different views and aspects. I believe this topic was vital to research because it give us insight on were the music industry is headed in the future. Two main research questions proposed were; “How is digital music distribution affecting the music industry?” and “In what way does the piracy industry affect the digital music industry?” The methodology used for this research was performing case studies, researching prospective and retrospective data, and analyzing sales figures and graphs. Case studies were performed on one independent artist and two major artists whom changed the digital music industry in different ways. Another pair of case studies were performed on an independent label and a major label on how changes of the digital music industry effected their business model and how piracy effected those new business models as well. I analyzed sales figures and graphs of digital music sales and physical sales to show the differences in the formats. I researched prospective data on how consumers adjusted to the digital music advancements and how piracy industry has affected them. Last I concluded all the data found during this research to show that digital music distribution is growing and could possibly be the dominant format for obtaining music, and the battle with piracy will be an ongoing process that will be hard to end anytime soon. -

1 the Versions Project: Exploring

THE VERSIONS PROJECT: EXPLORING MASHUP CULTURE By FRANCESCA LYN SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: Benjamin DeVane, CHAIR Melinda McAdams, MEMBER James Oliverio, MEMBER A PROJECT IN LIEU OF THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF 1 MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2011 2 ©2011 Francesca Lyn To everyone who has encouraged me to never give up, this would have never happened without all of you. 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS It is a pleasure to thank the many people who made this thesis possible. Thank you to my thesis chair Professor Ben DeVane and to my committee. I know that I was lucky enough to be guided by experts in their fields and I am extremely grateful for all of the assistance. I am grateful for every mashup artist that filled out a survey or simply retweeted a link. Special thanks goes to Kris Davis, the architect of idealMashup who encouraged me to become more of an activist with my work. And thank you to my parents and all of my friends. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………………………………….4 ABSTRACT……..………………………………………………………………………………...6 INTRODUCTION..……………………………………………………………………………….7 Remix Culture and Broader Forms………………………………………………………………..9 EARLY ANTECEDENTS………………………………………………………………………10 Hip-hop…………………………………………………………………………………………..11 THE MODERN MASHUP ERA………………………………………………………………..13 NEW MEDIA ARTIFACTS…………………………………………………………………….14 The Hyperreal……………………………………………………………………………………15 Properties of New Media………………………………………………………………………...17 Community……………………………………………………………………………...…18 -

Aster Marketing Thesi

ERASMUS SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS DEPARTMENT OF BUSINESS ECONOMICS - MARKETING MASTER THESIS It's All in the Lyrics: The Predictive Power of Lyrics Date : August, 2014 Name : Maarten de Vos Student ID : 331082 Supervisor : Dr. F. Deutzmann Abstract: This research focuses on whether it is possible to determine popularity of a specific song based on its lyrics. The songs which were considered were in the US Billboard Top 40 Singles Chart between 2006 and 2011. From this point forward, k-means clustering in RapidMiner has been used to determine the content that was present in the songs. Furthermore, data from Last.FM was used to determine the popularity of a song. This resulted in the conclusion that up to a certain extent, it is possible to determine popularity of songs. This is mostly applicable to the love theme, but only in the specific niches of it. Keywords: Content analysis, RapidMiner, Lyric analysis, Last.FM, K-means clustering, US Billboard Top 40 Singles Chart, Popularity 1 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 4 2. Motivation ........................................................................................................................................ 5 2.1. Academic contribution .............................................................................................................. 5 2.2. Managerial contribution .......................................................................................................... -

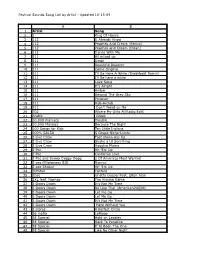

FS Master List-10-15-09.Xlsx

Festival Sounds Song List by Artist - Updated 10-15-09 A B 1 Artist Song 2 1 King Of House 3 112 U Already Know 4 112 Peaches And Cream (Remix) 5 112 Peaches and Cream [Clean] 6 112 Dance With Me 7 311 All mixed up 8 311 Down 9 311 Beautiful Disaster 10 311 Come Original 11 311 I'll Be Here A While (Breakbeat Remix) 12 311 I'll Be here a while 13 311 Love Song 14 311 It's Alright 15 311 Amber 16 311 Beyond The Grey Sky 17 311 Prisoner 18 311 Rub-A-Dub 19 311 Don't Tread on Me 20 702 Where My Girls At(Radio Edit) 21 Arabic Greek 22 10,000 maniacs Trouble 23 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night 24 100 Songs for Kids Ten Little Indians 25 100% SALSA S Grupo Niche-Lluvia 26 2 Live Crew Face Down Ass Up 27 2 Live Crew Shake a Lil Somthing 28 2 Live Crew Hoochie Mama 29 2 Pac Hit 'Em Up 30 2 Pac California Love 31 2 Pac and Snoop Doggy Dogg 2 Of Americas Most Wanted 32 2 pac f/Notorious BIG Runnin' 33 2 pac Shakur Hit 'Em Up 34 20thfox Fanfare 35 2pac Ghetto Gospel Feat. Elton John 36 2XL feat. Nashay The Kissing Game 37 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 38 3 Doors Down Be Like That (AmericanPieEdit) 39 3 Doors Down Let me Go 40 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 41 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 42 3 Doors Down Here Without You 43 3 Libras A Perfect Circle 44 36 mafia Lollipop 45 38 Special Hold on Loosley 46 38 Special Back To Paradise 47 38 Special If Id Been The One 48 38 Special Like No Other Night Festival Sounds Song List by Artist - Updated 10-15-09 A B 1 Artist Song 49 38 Special Rockin Into The Night 50 38 Special Saving Grace 51 38 Special Second Chance 52 38 Special Signs Of Love 53 38 Special The Sound Of Your Voice 54 38 Special Fantasy Girl 55 38 Special Caught Up In You 56 38 Special Back Where You Belong 57 3LW No More 58 3OH!3 Don't Trust Me 59 4 Non Blondes What's Up 60 50 Cent Just A Lil' Bit 61 50 Cent Window Shopper (Clean) 62 50 Cent Thug Love (ft. -

Audiences, Gender and Community in Fan Vidding Katharina M

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2011 "Veni, Vidi, Vids!" audiences, gender and community in Fan Vidding Katharina M. Freund University of Wollongong, [email protected] Recommended Citation Freund, Katharina M., "Veni, Vidi, Vids!" audiences, gender and community in Fan Vidding, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, School of Social Sciences, Media and Communications, Faculty of Arts, University of Wollongong, 2011. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/3447 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] “Veni, Vidi, Vids!”: Audiences, Gender and Community in Fan Vidding A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree Doctor of Philosophy From University of Wollongong by Katharina Freund (BA Hons) School of Social Sciences, Media and Communications 2011 CERTIFICATION I, Katharina Freund, declare that this thesis, submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Arts Faculty, University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Katharina Freund 30 September, 2011 i ABSTRACT This thesis documents and analyses the contemporary community of (mostly) female fan video editors, known as vidders, through a triangulated, ethnographic study. It provides historical and contextual background for the development of the vidding community, and explores the role of agency among this specialised audience community. Utilising semiotic theory, it offers a theoretical language for understanding the structure and function of remix videos. -

Narrative Representations of Gender and Genre Through Lyric, Music, Image, and Staging in Carrie Underwood’S Blown Away Tour

COUNTRY CULTURE AND CROSSOVER: Narrative Representations of Gender and Genre Through Lyric, Music, Image, and Staging in Carrie Underwood’s Blown Away Tour Krisandra Ivings A Thesis Presented In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree Master of Arts in Music with Specialization in Women’s Studies University of Ottawa © Krisandra Ivings, Ottawa, Canada, 2016 Abstract This thesis examines the complex and multi-dimensional narratives presented in the work of mainstream female country artist Carrie Underwood, and how her blending of musical genres (pop, rock, and country) affects the narratives pertaining to gender and sexuality that are told through her musical texts. I interrogate the relationships between and among the domains of music, lyrics, images, and staging in Underwood’s live performances (Blown Away Tour: Live DVD) and related music videos in order to identify how these gendered narratives relate to genre, and more specifically, where these performances and videos adhere to, expand on, or break from country music tropes and traditions. Adopting an interlocking theoretical approach grounded in genre theory, gender theory, narrative theory in the context of popular music, and happiness theory, I examine how, as a female artist in the country music industry, Underwood uses genre-blending to construct complex gendered narratives in her musical texts. Ultimately, I find that in her Blown Away Tour: Live DVD, Underwood uses diverse narrative strategies, sometimes drawing on country tropes, to engage techniques and stylistic influences of several pop and rock styles, and in doing so explores the gender norms of those genres. ii Acknowledgements A great number of people have supported this thesis behind the scenes, whether financially, academically, or emotionally. -

The Glenville Mercury

The Glenville Mercury Number 8 Glenville State College, Glenville, West Virginia Friday, October 19 , 1979 Registrar Announces Band To Play December Graduates Get your feet ready for some The following is a list of those Wells, Parkersburg, Elem. 1-6, lang foot stomp in' music! Bluegrass lovers students who will be graduating uage Arts 4-8, Social Studies 4-8; beware! The Plum Hollow Band December 21,1979. Those students Nancy Elizabeth Cox Wells, Penns is a musical experience that is taking who are not on this list but should boro, Elementary 1-6; Kathleen Ann the country by surprise. The band be, or those who are on it and Harper White, Pennsboro, Elem./ is planning a concert here, at the should not be, should contact Mrs. Early Educ. N-K-6; Kim Elaine White, college auditorium, Nov. I at 8 p.m. Jean Spurgeon in the Registrar's Weston, Social Studies Comp. 7-12; Office as soon as possible. Wilbert Jay Zirkle, Buckhannon, The five man bluegrass band hails Gregory Oliver Arnette, Char· Phys. Educ. K-12, Safety Educ. 7-12. from Nortll Carolina, and has played lottesville, VA, Physical Education gigs from North Carolina to Mon K-12, Health Education K·12; Ad· Gary Frank Bonnett, Troy, Ac tana. The band, wh ich has been to rian Douglas Bailey , J r., Rich wood, counting, Management; John RuSsell gether three years, has been on stage Music K-12; Teresa Lynn Barnett, Caldwell, Hannibal, OH, Marketing with such notable names as: "Nitty Kenna, Elem. 1-6, Mental Retard and Retailing; John Charles Caltrider, Science Series To Be Presented Gritty Dirt Band," "Pablo Cruise," ation Spec. -

View Full Article

ARTICLE ADAPTING COPYRIGHT FOR THE MASHUP GENERATION PETER S. MENELL† Growing out of the rap and hip hop genres as well as advances in digital editing tools, music mashups have emerged as a defining genre for post-Napster generations. Yet the uncertain contours of copyright liability as well as prohibitive transaction costs have pushed this genre underground, stunting its development, limiting remix artists’ commercial channels, depriving sampled artists of fair compensation, and further alienating netizens and new artists from the copyright system. In the real world of transaction costs, subjective legal standards, and market power, no solution to the mashup problem will achieve perfection across all dimensions. The appropriate inquiry is whether an allocation mechanism achieves the best overall resolution of the trade-offs among authors’ rights, cumulative creativity, freedom of expression, and overall functioning of the copyright system. By adapting the long-standing cover license for the mashup genre, Congress can support a charismatic new genre while affording fairer compensation to owners of sampled works, engaging the next generations, and channeling disaffected music fans into authorized markets. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................ 443 I. MUSIC MASHUPS ..................................................................... 446 A. A Personal Journey ..................................................................... 447 B. The Mashup Genre .................................................................... -

Song List 2012

SONG LIST 2012 www.ultimamusic.com.au [email protected] (03) 9942 8391 / 1800 985 892 Ultima Music SONG LIST Contents Genre | Page 2012…………3-7 2011…………8-15 2010…………16-25 2000’s…………26-94 1990’s…………95-114 1980’s…………115-132 1970’s…………133-149 1960’s…………150-160 1950’s…………161-163 House, Dance & Electro…………164-172 Background Music…………173 2 Ultima Music Song List – 2012 Artist Title 360 ft. Gossling Boys Like You □ Adele Rolling In The Deep (Avicii Remix) □ Adele Rolling In The Deep (Dan Clare Club Mix) □ Afrojack Lionheart (Delicious Layzas Moombahton) □ Akon Angel □ Alyssa Reid ft. Jump Smokers Alone Again □ Avicii Levels (Skrillex Remix) □ Azealia Banks 212 □ Bassnectar Timestretch □ Beatgrinder feat. Udachi & Short Stories Stumble □ Benny Benassi & Pitbull ft. Alex Saidac Put It On Me (Original mix) □ Big Chocolate American Head □ Big Chocolate B--ches On My Money □ Big Chocolate Eye This Way (Electro) □ Big Chocolate Next Level Sh-- □ Big Chocolate Praise 2011 □ Big Chocolate Stuck Up F--k Up □ Big Chocolate This Is Friday □ Big Sean ft. Nicki Minaj Dance Ass (Remix) □ Bob Sinclair ft. Pitbull, Dragonfly & Fatman Scoop Rock the Boat □ Bruno Mars Count On Me □ Bruno Mars Our First Time □ Bruno Mars ft. Cee Lo Green & B.O.B The Other Side □ Bruno Mars Turn Around □ Calvin Harris ft. Ne-Yo Let's Go □ Carly Rae Jepsen Call Me Maybe □ Chasing Shadows Ill □ Chris Brown Turn Up The Music □ Clinton Sparks Sucks To Be You (Disco Fries Remix Dirty) □ Cody Simpson ft. Flo Rida iYiYi □ Cover Drive Twilight □ Datsik & Kill The Noise Lightspeed □ Datsik Feat. -

Империя Jay Z: Как Парень С Улицы Попал В Список Forbes Zack O'malley Greenburg Empire State of Mind: How Jay Z Went from Street Corner to Corner Office

Зак Гринберг Империя Jay Z: Как парень с улицы попал в список Forbes Zack O'Malley Greenburg Empire State of Mind: How Jay Z Went from Street Corner to Corner Office Copyright © 2011, 2012, 2015 by Zack O’Malley Greenburg All rights reserved including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. This edition published by arrangement with Portfolio, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC © Гусева А., перевод, 2017 © Оформление. ООО «Издательство «Эксмо», 2017 * * * Введение Четвертого октября 1969 года в 00 часов 10 минут по верхнему уровню Мертл- авеню в последний раз прогрохотал поезд наземки, навсегда скрывшись в ночи[1]. Два месяца спустя Шон Кори Картер, более известный как Jay Z, появился на свет и обрел свой первый дом в расположенном поблизости Марси Хаузес. Сейчас этот раскинувшийся на значительной территории комплекс однообразных шестиэтажных кирпичных зданий отделен пятью жилыми блоками от призрачных руин линии Мертл- авеню, вытянутой полой конструкции, которую никто так и не потрудился снести. В годы формирования личности Jay Z остальная территория Бедфорд-Стайвесант подобным же образом игнорировалась властями. В 1980-е, с расцветом наркоторговли, уроки спроса и предложения можно было получить за каждым углом. Прошлое Марси до сих пор дает о себе знать: железные ворота с внушительными замками, охраняющие парковочные места; номера квартир, белой краской выписанные по трафарету под каждым окном, выходящим на улицу, призванные помочь полиции в поисках скрывающихся преступников; и, конечно, скелет железной дороги над Мертл-авеню, буквально в нескольких шагах от современной станции, на которой теперь останавливаются поезда маршрутов J и Z. На этих страницах вы найдете подробную историю пути Jay Z от безрадостных улиц Бруклина к высотам мира бизнеса. -

Marygold Manor DJ List

Page 1 of 143 Marygold Manor 4974 songs, 12.9 days, 31.82 GB Name Artist Time Genre Take On Me A-ah 3:52 Pop (fast) Take On Me a-Ha 3:51 Rock Twenty Years Later Aaron Lines 4:46 Country Dancing Queen Abba 3:52 Disco Dancing Queen Abba 3:51 Disco Fernando ABBA 4:15 Rock/Pop Mamma Mia ABBA 3:29 Rock/Pop You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC 3:30 Rock You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC 3:30 Rock You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC 3:31 Rock AC/DC Mix AC/DC 5:35 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap ACDC 3:51 Rock/Pop Thunderstruck ACDC 4:52 Rock Jailbreak ACDC 4:42 Rock/Pop New York Groove Ace Frehley 3:04 Rock/Pop All That She Wants (start @ :08) Ace Of Base 3:27 Dance (fast) Beautiful Life Ace Of Base 3:41 Dance (fast) The Sign Ace Of Base 3:09 Pop (fast) Wonderful Adam Ant 4:23 Rock Theme from Mission Impossible Adam Clayton/Larry Mull… 3:27 Soundtrack Ghost Town Adam Lambert 3:28 Pop (slow) Mad World Adam Lambert 3:04 Pop For Your Entertainment Adam Lambert 3:35 Dance (fast) Nirvana Adam Lambert 4:23 I Wanna Grow Old With You (edit) Adam Sandler 2:05 Pop (slow) I Wanna Grow Old With You (start @ 0:28) Adam Sandler 2:44 Pop (slow) Hello Adele 4:56 Pop Make You Feel My Love Adele 3:32 Pop (slow) Chasing Pavements Adele 3:34 Make You Feel My Love Adele 3:32 Pop Make You Feel My Love Adele 3:32 Pop Rolling in the Deep Adele 3:48 Blue-eyed soul Marygold Manor Page 2 of 143 Name Artist Time Genre Someone Like You Adele 4:45 Blue-eyed soul Rumour Has It Adele 3:44 Pop (fast) Sweet Emotion Aerosmith 5:09 Rock (slow) I Don't Want To Miss A Thing (Cold Start)