A Better Chance, an Educational Program. Abc Report, 1964

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maine Campus March 22 1928 Maine Campus Staff

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Maine Campus Archives University of Maine Publications Spring 3-22-1928 Maine Campus March 22 1928 Maine Campus Staff Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainecampus Repository Citation Staff, Maine Campus, "Maine Campus March 22 1928" (1928). Maine Campus Archives. 3384. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainecampus/3384 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine Campus Archives by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. L. ue Meeting Tije ofiftitthr Canyttil Al meeting; Published Weekly by the Students of the University of Maine of Maine ten warm No. 21 MAINE, MARCH 22, 1928 trticipatieg Vol. XXIX ORONO, P indicates (I numbers. WIN COMpeted HEBRON ACADEMY AND BLUE BOOK OF SPORTS ENGLISH DEPARTMENT SENIOR ENGINEERS MAINE DEBATERS OVER leloted to- HARBOR HIGH WIN HONORS BILL KENYON ANNOUNCES NAMES OF ON INSPECTION TRIP• DOUBLE VICTORY ;iould be a BAR ion with a "Who's Who in Sportdom," a blue boa HIGH RANKING MAJORS COLBY CONTESTANTS BASKETBALL TOURNEY Civil. Electrical, Newt. Thk. of sports, published by the National lb, — SI-- partments oi t Iwtutcal. y logical Society has inserted the name kit and Nlechanical Engineering are on their THREE- are in WATERVILLE AND ORONO JUDGES St se%eral FAST AND INTERESTING GAMES William C. ("Bill') Kenyon on its roll MARGUERITE STANLEY, annual inspection trip. The men at onsideral4 of honor. lb tst. al and have their headquarters FAVOR BLUE REPRESENTATIVES ARE PLAYED IN BOTH YEAR STUDENT, LEADS began March red. -

King's Academy

KING’S ACADEMY Madaba, Jordan Associate Head of School for Advancement August 2018 www.kingsacademy.edu.jo/ The Position King’s Academy in Jordan is the realization of King Abdullah’s vision to bring quality independent boarding school education to the Levant as a means of educating the next generation of regional and global leaders and building international collaboration, peace, and understanding. Enrolling 670 students in grades 7-12, King’s Academy offers an educational experience unique in the Middle East—one that emulates the college-preparatory model of American boarding schools while at the same time upholding and honoring a distinctive MISSION Middle Eastern identity. Since the School’s founding in 2007, students from Jordan, throughout the Middle East, and other In a setting that is rich in history nations from around the world have found academic challenge and tradition, King’s Academy and holistic development through King’s Academy’s ambitious is committed to providing academic and co-curricular program, which balances their a comprehensive college- intellectual, physical, creative, and social development. preparatory education through a challenging curriculum in the arts and sciences; an integrated From the outset, King’s Academy embraced a commitment co-curricular program of athletics, to educational accessibility, need-based financial aid, and activities and community service; diversity. Over 40 countries are represented at King’s, and and a nurturing residential approximately 74% of students reside on campus. More than environment. Our students 45% of the student body receives financial aid at King’s, and the will learn to be independent, School offers enrichment programs to reach underprivileged creative and responsible thinkers youth in Jordan (see Signature Programs). -

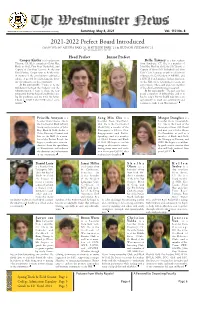

2021-2022 Prefect Board Introduced - - - Times

Westminster School Simsbury, CT 06070 www.westminster-school.org Saturday, May 8, 2021 Vol. 110 No. 8 2021-2022 Prefect Board Introduced COMPILED BY ALEYNA BAKI ‘21, MATTHEW PARK ‘21 & HUDSON STEDMAN ‘21 CO-EDITORS-IN-CHIEF, 2020-2021 Head Prefect Junior Prefect Cooper Kistler is a boarder from Bella Tawney is a day student Tiburon, CA. He is a member of John Hay, from Simsbury, CT. She is a member of Black & Gold, First Boys’ Basketball, and John Hay, Black & Gold, the SAC Board, a Captain of First Boys’ lacrosse. As the new Captain of First Girls’ Basketball and First Head Prefect, Cooper aims to be the voice Girls’ Cross Country, as well as a Horizons of everyone in the community to cultivate a volunteer, the Co-President of AWARE, and culture of growth by celebrating the diver- a HOTH board member. In her final year sity of perspectives in the community. on the Hill, she is determined to create an In his own words: “I want to be the environment, where each and every member middleman between the Students and the of the school community feels accepted. Administration. I want to share the new In her own words: “The past year has perspective that we have all established dur- posed a number of difficulties, and it is ing the pandemic, and use it for the better. hard to adapt, but we should take this as an I want to UNITE the NEW school com- opportunity to teach our community and munity." continue to make it our Westminster." Priscilla Ameyaw is a Sung Min Cho is a Margot Douglass is a boarder from Ghana. -

May 26, 2021 Dear Whitfield School Community: on Behalf of the Board

Whitfield School 175 S. Mason Road Saint Louis, Missouri 63141 (314) 434-5141 www.whitfieldschool.org May 26, 2021 Dear Whitfield School Community: On behalf of the Board of Trustees, I am pleased to announce that Chris Cunningham has accepted our invitation to serve as the next Head of Whitfield School, effective July 1, 2022. As you know, John Delautre will be retiring at the end of the 2021-2022 academic year after 10 years of outstanding service to our School, and we will enjoy his leadership for the next fourteen months, thus ensuring a smooth transition. Beginning in January 2021, the Search Committee, chaired by Karen Myers, worked with search consultants Nat Conard and Deirdre Ling of Educators’ Collaborative, and reviewed the credentials of candidates from throughout the U.S. and abroad. The Committee narrowed the pool of candidates to eight individuals who were invited for a confidential round of virtual interviews. Subsequently, four finalists and spouses/partners visited the campus for comprehensive two-day interviews. On May 20, the Search Committee selected Chris Cunningham as its nominee to the Board of Trustees to serve as the next Head of School. The Trustees unanimously ratified this recommendation at a Board meeting on May 25. Chris has spent the past twenty-five years in independent school education. Receiving a bachelor’s degree in Modern Thought and Literature from Stanford University in 1989, he graduated Phi Beta Kappa with Distinction and Honors. He went on to complete a Ph.D. in English from Duke University in 1996. Beginning his independent school teaching career as a 9th and 11th grade English teacher at Montclair Kimberley Academy, Chris later taught at Stuart Country Day School of the Sacred Heart and Princeton Day School before joining the faculty at The Lawrenceville School in Lawrenceville, NJ, where he is currently the Assistant Head of School and Dean of Faculty, having served since 2003 as English teacher, Head of House, Advisor, and Varsity Coach. -

School Brochure

Bring Global Diversity to Your Campus with ASSIST 52 COUNTRIES · 5,210 ALUMNI · ONE FAMILY OUR MISSION ASSIST creates life-changing opportunities for outstanding international scholars to learn from and contribute to the finest American independent secondary schools. Our Vision WE BELIEVE that connecting future American leaders with future “Honestly, she made me think leaders of other nations makes a substantial contribution toward about the majority of our texts in brand new ways, and increasing understanding and respect. International outreach I constantly found myself begins with individual relationships—relationships born taking notes on what she through a year of academic and cultural immersion designed would say, knowing that I to affect peers, teachers, friends, family members and business would use these notes in my teaching of the course associates for a lifetime. next year.” WE BELIEVE that now, more than ever, nurturing humane leaders “Every time I teach this course, there is at least one student through cross-cultural interchange affords a unique opportunity in my class who keeps me to influence the course of future world events in a positive honest. This year, it’s Carlota.” direction. “Truly, Carlota ranks among the very best of all of the students I have had the opportunity to work with during my nearly 20 years at Hotchkiss.” ASSIST is a nonprofit organization that works closely with American independent secondary Faculty members schools to achieve their global education and diversity objectives. We identify, match The Hotchkiss School and support academically talented, multilingual international students with our member Connecticut schools. During a one-year school stay, an ASSIST scholar-leader serves as a cultural ambassador actively participating in classes and extracurricular activities. -

Medical School Basic Science Clinical Other Total Albany Medical

Table 2: U.S. Medical School Faculty by Medical School and Department Type, 2020 The table below displays the number of full-time faculty at all U.S. medical schools as of December 31, 2020 by medical school and department type. Medical School Basic Science Clinical Other Total Albany Medical College 74 879 48 1,001 Albert Einstein College of Medicine 316 1,895 21 2,232 Baylor College of Medicine 389 3,643 35 4,067 Boston University School of Medicine 159 1,120 0 1,279 Brody School of Medicine at East Carolina University 92 349 0 441 CUNY School of Medicine 51 8 0 59 California Northstate University College of Medicine 5 13 0 18 California University of Science and Medicine-School of Medicine 26 299 0 325 Carle Illinois College of Medicine 133 252 0 385 Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine 416 2,409 0 2,825 Central Michigan University College of Medicine 21 59 0 80 Charles E. Schmidt College of Medicine at Florida Atlantic University 30 64 0 94 Chicago Medical School at Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine & Science 69 25 0 94 Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons 282 1,972 0 2,254 Cooper Medical School of Rowan University 78 608 0 686 Creighton University School of Medicine 52 263 13 328 Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell 88 2,560 9 2,657 Drexel University College of Medicine 98 384 0 482 Duke University School of Medicine 297 998 1 1,296 East Tennessee State University James H. -

Next Schools - 2006-2020

THE LEARNING PROJECT - NEXT SCHOOLS - 2006-2020 2020 2019 2018 Boston College High School (2) Boston College High School Boston Latin Academy Boston Latin School (7) Beaver Country Day School (2) Boston Latin School (5) Brimmer and May Cathedral High School (2) Boston Latin Academy Boston Latin School (5) Fessenden School Dana Hall School (2) Brimmer and May Georgetown Day (Washington, D.C.) The Newman School Linden STEAM Academy Milton Academy The Pierce School Newton Country Day School (2) Thew Newman School The Newman School Newton Country Day School The Rivers School Roxbury Latin School (2) Roxbury Latin School 2017 2016 2015 BC High (2) BC High Boston Latin School (6) Boston Latin Academy Beaver Country Day (2) BC High Boston Latin School (8) Boston Latin School (4) Belmont Hill Brimmer and May Buckingham, Brown, & Nichols Buckingham, Browne & Nichols Milton Academy Fessenden Cathedral High Thayer Academy John D. O’Bryant High School Park School Ursuline Milton Academy (2) Rivers Newton Country Day Winsor (3) Winsor Other Public (2) 2014 2013 2012 Boston Latin School (9) Boston Latin Academy Boston Latin Academy Buckingham, Browne & Nichols (3) Boston Latin School (5) Boston Latin School (9) Catholic Memorial Beaver Country Day BC High Roxbury Latin School (2) BC High Brimmer & May Brimmer & May (2) Cambridge Friends Milton Academy Milton Academy Newton Country Day Shady Hill Roxbury Latin School Ursuline Academy Winsor Concord Public Brookline Public (2) 2011 2010 2009 Boston Latin Academy Boston Latin Academy Boston Latin Academy -

MD Class of 2021 Commencement Program

Commencement2021 Sunday, the Second of May Two Thousand Twenty-One Mount Airy Casino Resort Mt. Pocono, Pennsylvania Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine celebrates the conferring of Doctor of Medicine degrees For the live-stream event recording and other commencement information, visit geisinger.edu/commencement. Commencement 2021 1 A message from the president and dean Today we confer Doctor of Medicine degrees upon our our past, but we are not afraid to evolve and embrace ninth class. Every year at commencement, I like to reflect innovation, change and our future. To me, this courage, on the ways in which each class is unique. The Class resilience and creative thinking have come to be of 2021 presents an interesting duality. It is the first of synonymous with a Geisinger Commonwealth School some things and also the last of many. Like the Roman of Medicine diploma — and I have received enough god Janus, this class is one that looks back on our past, feedback from fellow physicians, residency program but also forward to the future we envision for Geisinger directors and community members to know others Commonwealth School of Medicine. believe this, too. Every student who crosses the stage Janus was the god of doors and gates, of transitions today, through considerable personal effort, has earned and of beginnings and ends. It is an apt metaphor, the right to claim the privileges inherent in because in so many ways yours has been a transitional that diploma. class. You are the last class to be photographed on Best wishes, Class of 2021. I know that the experiences, the day of your White Coat Ceremony wearing jackets growth and knowledge bound up in your piece of emblazoned “TCMC.” You are also, however, the first parchment will serve you well and make us proud in the class offered the opportunity of admittance to the Abigail years to come. -

The Official Boarding Prep School Directory Schools a to Z

2020-2021 DIRECTORY THE OFFICIAL BOARDING PREP SCHOOL DIRECTORY SCHOOLS A TO Z Albert College ON .................................................23 Fay School MA ......................................................... 12 Appleby College ON ..............................................23 Forest Ridge School WA ......................................... 21 Archbishop Riordan High School CA ..................... 4 Fork Union Military Academy VA ..........................20 Ashbury College ON ..............................................23 Fountain Valley School of Colorado CO ................ 6 Asheville School NC ................................................ 16 Foxcroft School VA ..................................................20 Asia Pacific International School HI ......................... 9 Garrison Forest School MD ................................... 10 The Athenian School CA .......................................... 4 George School PA ................................................... 17 Avon Old Farms School CT ...................................... 6 Georgetown Preparatory School MD ................... 10 Balmoral Hall School MB .......................................22 The Governor’s Academy MA ................................ 12 Bard Academy at Simon's Rock MA ...................... 11 Groton School MA ................................................... 12 Baylor School TN ..................................................... 18 The Gunnery CT ........................................................ 7 Bement School MA................................................. -

An Open Letter on Behalf of Independent Schools of New England

An Open Letter on Behalf of Independent Schools of New England, We, the heads of independent schools, comprising 176 schools in the New England region, stand in solidarity with our students and with the families of Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida. The heart of our nation has been broken yet again by another mass shooting at an American school. We offer our deepest condolences to the families and loved ones of those who died and are grieving for the loss of life that occurred. We join with our colleagues in public, private, charter, independent, and faith-based schools demanding meaningful action to keep our students safe from gun violence on campuses and beyond. Many of our students, graduates, and families have joined the effort to ensure that this issue stays at the forefront of the national dialogue. We are all inspired by the students who have raised their voices to demand change. As school leaders we give our voices to this call for action. We come together out of compassion, responsibility, and our commitment to educate our children free of fear and violence. As school leaders, we pledge to do all in our power to keep our students safe. We call upon all elected representatives - each member of Congress, the President, and all others in positions of power at the governmental and private-sector level – to take action in making schools less vulnerable to violence, including sensible regulation of fi rearms. We are adding our voices to this dialogue as a demonstration to our students of our own commitment to doing better, to making their world safer. -

Tuitions Paid in FY2013 by Vermont Districts to Out-Of-State Public And

Tuitions Paid in FY2013 by Vermont Districts to Out-of-State Page 1 Public and Independent Schools for Regular Education LEA id LEA paying tuition S.U. Grade School receiving tuition City State FTE Tuition Tuition Paid Level 331.67 Rate 3,587,835 T003 Alburgh Grand Isle S.U. 24 Sec Clinton Community College Champlain NY 1.00 165 165 College T003 Alburgh 24 Sec Northeastern Clinton Central School District Champlain NY 14.61 9,000 131,481 Public T003 Alburgh 24 Sec Paul Smith College Paul Smith NY 2.00 120 240 College T010 Barnet Caledonia Central S.U. 09 Sec Haverhill Cooperative Middle School Haverhill NH 0.50 14,475 7,238 Public T021 Bloomfield Essex North S.U. 19 Sec Colebrook School District Colebrook NH 9.31 16,017 149,164 Public T021 Bloomfield 19 Sec Groveton High School Northumberland NH 3.96 14,768 58,547 Public T021 Bloomfield 19 Sec Stratford School District Stratford NH 1.97 13,620 26,862 Public T035 Brunswick Essex North S.U. 19 Sec Colebrook School District Colebrook NH 1.50 16,017 24,026 Public T035 Brunswick 19 Sec Northumberland School District Groveton NH 2.00 14,506 29,011 Public T035 Brunswick 19 Sec White Mountain Regional School District Whitefiled NH 2.38 14,444 34,409 Public T036 Burke Caledonia North S.U. 08 Sec AFS-USA Argentina 1.00 12,461 12,461 Private T041 Canaan Essex North S.U. 19 Sec White Mountain Community College Berlin NH 39.00 150 5,850 College T048 Chittenden Rutland Northeast S.U. -

Recent Senior Administrative Searches

RECENT SENIOR ADMINISTRATIVE SEARCHES This sampling of recent senior administrative searches illustrates the broad range of schools we serve and the strength of their appointees. ETHICAL CULTURE FIELDSTON SCHOOL NEW YORK, NY (2018-19) Since its founding in 1878, Ethical Culture Fieldston School has been a beacon of progressive education in America. Known among New York City independent schools as a place where children are simultaneously encouraged to revel in the joys of childhood and confront the challenges presented by the modern world, ECFS emphasizes ethical thinking, academic excellence, and student-centered learning. PRINCIPAL, FIELDSTON UPPER - Nigel Furlonge was Associate Head of School at Holderness School from 2015-2018 before his appointment at ECFS. Previous posts include Admissions Director and Dean of Students and Residential Life at Christina Seix Academy, Academic Dean at The Lawrenceville School, and Director of Studies at St. Andrew’s School (DE). Nigel is a graduate of Boston Latin School and holds a B.A. in American History with a minor in African American Studies from The University of Pennsylvania, an M.A. in American History from Villanova University, and an M.Ed. in Organization and Private School Leadership from Columbia University. PRINCIPAL, FIELDSTON LOWER - Joseph McCauley previously served as Assistant Head of Pre- and Lower School at The Packer Collegiate Institute before joining Fieldston. He joined Packer in 2008 as a fourth-grade teacher. During his time there, he was Director of the Teacher Mentor Program, Leader of Yearlong Staff Development Groups, and a member of the Lower School Curriculum Leadership Team, as well as the Strategic Plan Task Force on Community and Identity.