Key Factors in Measuring Ammonia Emissions with Dynamic Flux Chamber in Barns

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

STAINLESS STEEL Flux Coated

U.S. ALLOY CO. STAINLESS STEEL dba Washington Alloy 7010-G Reames Rd. Charlotte, NC 28216 Flux Coated Tig www.weldingwire.com Quality Management System in accordance with ISO 9001:2000 Cert # 05-R0925 ALLOY DESCRIPTION AND APPLICATION; These flux coated rods are primarily used for the root pass on piping where backing and purging gas may not be possible or desirable. This 39” rod should be used as a basic tig rod on DCEN, however caution is advised due to the easily removable slag covering that must be removed prior to addition welding. TYPICAL GTAW WELDING PROCEDURES; DCEN Wire Diameter Amps Volts 5/64” 90-180 12-13 3/32” 150-250 12-13 1/8” 200-375 12-14 Procedures may vary with change in position, base metals, filler metals, equipment and other changes. TYPICAL UNDILUTED METAL CHEMISTRY (%) per AWS A5.22; Chemistry Grade 1) Intended Use C Cr Ni Mo R308L 0.03 18.0-21.0 9.0-11.0 0.50 Welding of 18Cr & 8Ni such as 304, 304L R308H3) 0.04-0.08 19.5-22.0 9.0-11.0 0.50 Welding of 18Cr & 8Ni such as 304, 304H R309L 0.03 22.0-25.0 12.0-14.0 0.50 Welding of carbon steel to austenitic stainless R316L 0.03 17.0-20.0 11.0-14.0 2.0-3.0 Primarily use on 316 or 316L R347 2) 0.08 18.0-21.0 9.0-11.0 0.50 Primarily use on 347 1) All grades has the following : Mn=0.50-2.5, Si=1.2, P=0.04, S=0.03 Cu=0.50 Single values are maximum 2) R347 also has Cb+Ta =8xCmin. -

General Purpose Liquid Soldering Flux

Weldcote Metals 842 Oak Grove Rd. Kings Mountain, NC 28086 704-739-4115 www.weldcotemetals.com WELDCOTE GENERAL PURPOSE LIQUID SOLDERING FLUX General Purpose Liquid Soldering Flux Formulated for soldering Stainless Steel and High-Chrome Alloys. Excellent across a broad range of base metals, solders, and temperatures. Exhibits excellent capillary action. DESCRIPTION Weldcote Liquid Soldering Flux is a water-based, general purpose, inorganic-acid flux formulated for soldering stainless steel and other industrial metals. The flux contains Zinc Chloride, Ammonium Chloride, and Hydrochloric Acid, that make this flux active at room temperature where it begins to clean metals and remove oxides. The flux exerts a strong scavenging action to remove oxide coatings and other impurities from the metal surface to produce strong joints. Pre-cleaning is not necessary under most conditions. APPLICATIONS Weldcote Liquid Soldering Flux is excellent for use on Stainless Steel, Monel, High-Chrome Alloys, Inconel, Nickel, Copper, Brass, Ferrous Alloys and many more metals. It is not recommended for Aluminum and Magnesium. DIRECTIONS Weldcote Liquid Soldering Flux may be applied with a brush, swab or by dipping. The flux exhibits the best activity between 93°C/200°F and 315°C/600°F. Post-solder residues are water-soluble and hot water rinses (140°F or higher) may be adequate for most applications. The following steps are recommended for optimum soldering results: • Remove any oil, grease, or other contaminants from the surface to be soldered. • Apply flux to joint by dipping, spraying, dragging, swabbing or brushing to area being soldered. • Preheat or air-dry area to be soldered after flux has been applied to activate the flux and yield optimum soldering characteristics and reduce or eliminate spattering. -

SOPRIN Flux Zinc Safety Data Sheet

Flux Zinc Safety Data Sheet SECTION 1: Identification 1.1. Product identifier Product form : Mixture Product name : Flux Zinc 1.2. Recommended use and restrictions on use Smelting / deoxidizing agent for hot dip galvanizing kettles. 1.3. Supplier SOPRIN S.r.l. Via dell’Industria 106 31052 Maserada Sul Piave (TV) - Italy T (+39) 0422 521025 - F (+39) 0422 521060 [email protected] (Alessandro Padovan) 1.4. Emergency telephone number Emergency number : (+39) 0422 521025 SECTION 2: Hazard identification 2.1. Classification of the substance or mixture Classification (GHS-US/ CAN) Skin corrosion/irritation Category 2 H315 Serious eye damage/eye irritation Category 2 H319 Full text of H statements : see section 16 2.2. GHS Label elements, including precautionary statements GHS-US/CAN labeling Hazard pictograms : Signal word : Danger Hazard statements : H315 - Causes skin irritation H319 - Causes serious eye irritation Precautionary statements : P264 - Wash thoroughly after handling P280 - Wear protective gloves/protective clothing/eye protection/face protection P302+P352 - IF ON SKIN: Wash with plenty of water P305+P351+P338 - IF IN EYES: Rinse cautiously with water for several minutes. Remove contact lenses, if present and easy to do. Continue rinsing P332+P313 - If skin irritation occurs: Get medical advice/attention P337+P313 - If eye irritation persists: Get medical advice/attention P362+P364 - Take off contaminated clothing and wash it before reuse 2.3. Other hazards No additional information available 2.4. Unknown acute toxicity (GHS-US/CAN) No data available SECTION 3: Composition/Information on ingredients 3.1. Substances Not applicable 3.2. Mixtures Name Product identifier % Classification (GHS-CA) GHS-US classification Ammonium chloride (CAS No) 12125-02-9 30 - 32.5 Acute Tox. -

Indalloy® Flux 3 97809 (A4) R1

PRODUCT DATA SHEET Indalloy® Flux #3 Introduction Technical Specifications Indalloy® Flux #3 is a high-viscosity liquid flux formulated Indium Part Number (IPN) 84003 for the purpose of soldering aluminum. Indalloy® Flux #3 Activation Range 96–343°C also has proven to be an effective flux for soldering to NiTi (Nitinol) alloys. Other metals for use with Indalloy® Flux #3 Specific Gravity 1.33gm/cc are: copper, brass, chrome, and stainless steel. Flash Point 93°C Due to its corrosive nature, Indalloy® Flux #3 is not Chloride Content Contains chlorides recommended for electronics applications. pH 8 Appearance Yellow to pale green Warm water (<50°C) and Cleaning Cleaning mechanical scrubbing Flux residue removal is mandatory and may be accomplished by means of warm water and mechanical scrubbing. Cleaning Transport in accordance with Shipping applicable regulations and should be performed as soon as possible after the soldering requirements operation to avoid corrosion. The cleaning water temperature All information is for reference only. should not exceed 50°C. Excessive water temperature may Not to be used as incoming product specifications. cause secondary reactions and result in corrosion and/or pitting. A warm water sonication may also be a means of flux residue removal. Technical Support Indium Corporation’s internationally experienced engineers Solder Alloy Compatibility provide in-depth technical assistance to our customers. Indalloy® Flux #3 works best with tin-containing alloys. It is Thoroughly knowledgeable in all facets of Material Science not recommended for indium-containing alloys due to indium’s as it applies to the electronics and semiconductor sectors, sensitivity to chloride-induced corrosion. -

Indalloy® Flux #2 97808 R1

PRODUCT DATA SHEET Indalloy® Flux #2 Introduction Technical Specifications Indalloy® Flux #2 is a specialty acid-based liquid flux Indium Part Number (IPN) 84002 formulated for the purpose of soldering high chromium- Activation Range 100–371°C containing alloys, including stainless steel. Indalloy® Flux #2 also has proven to be an effective flux for soldering to NiTi Specific Gravity 1.53gm/cc (Nitinol) alloys. Other metals for use with Indalloy® Flux #2 Flash Point Non-flammable are: copper, brass, lead, chrome, galvanized iron, and steel. No zinc or other heavy metal Chloride Content chlorides Due to its corrosive nature, Indalloy® Flux #2 is not recommended for electronics applications. pH 1–1.5 Appearance Water white Warm water (<50°C) and Cleaning Cleaning mechanical scrubbing Flux residue removal is mandatory and may be accomplished by Transport in accordance with means of warm water and mechanical scrubbing. Cleaning should Shipping applicable regulations and be performed as soon as possible after the soldering operation to requirements. ® avoid corrosion. Indalloy Flux #2 does not progressively corrode All information is for reference only. stainless steel (no neutralization necessary), but cleaning is still Not to be used as incoming product specifications. advisable as the flux/flux residue may still attack the solder. The cleaning water temperature should not exceed 50°C. Excessive water temperature may cause secondary reactions and result in Technical Support corrosion and/or pitting. A warm water sonication may also be a Indium Corporation’s internationally experienced engineers means of flux residue removal. The addition of Citric Acid to wash provide in-depth technical assistance to our customers. -

SHEETMETAL FABRICATION TECHNICAL TIPS for SOLDERING Flux

SHEETMETAL FABRICATION TECHNICAL TIPS FOR SOLDERING Flux In metallurgy, a flux (derived from Latin fluxus meaning “flow”), is a chemical cleaning agent, flowing agent, or purifying agent. Fluxes may have more than one function at a time. They are used in both metallurgy and metal joining. In high-temperature metal joining processes (welding, brazing and soldering), the primary purpose of flux is to prevent oxidation of the base and filler materials. Tin-lead solder (e.g.) attaches very well to copper, but poorly to the various oxides of copper, which form quickly at soldering temperatures. The role of a flux in joining processes is typically dual: 1. As cleaning agents, fluxes facilitate soldering by removing oxidation from the metals to be joined by dissolving the oxides on the metal surface, which facilitates wetting by molten solder. The flux also acts as an oxygen barrier by coating the hot surface, preventing further oxidation during the soldering process. 2. Additionally, flux allows solder to flow easily on the working piece rather than forming beads as it would otherwise. In some applications molten flux also serves as a heat transfer medium, facilitating heating of the joint by the soldering tool or molten solder. FLUX TYPES There are two types of fluxes used for soft soldering. These are organic (rosin based) fluxes or inorganic fluxes, usually based on halogenides and/or acids. Common fluxes are: ammonium chloride or rosin for soldering tin; hydrochloric acid and zinc chloride for soldering galvanized iron (and other zinc surfaces); and borax for brazing or braze-welding ferrous metals. -

Circuitworks® Tacky Flux

® CircuitWorks Tacky Flux: Use and Working Conditions By Milton Davis ® ITW Chemtronics 8125 Cobb Center Drive Kennesaw, GA 30152 770-424-4888 Tacky fluxes are commonly used in the electronics assembly industry for a variety of applications. These fluxes generally have honey-like consistency and can be used for ball attach applications, BGA re-balling and hand soldering applications. CircuitWorks® No-Clean Tacky Flux, part number CW8500, is a mildly activated rosin (RMA) no-clean tacky flux. Its formulation includes a unique rosin/resin blend coupled with a proprietary blend of activators and stabilizers, providing significantly increased shelf life and long-term product stability. This results in a post solder residue that is stable and can be left on a board without cleaning. Performance Characteristics CircuitWorks® No-Clean Tacky Flux offers a combination of a stable platform with robust activity. In this regard CircuitWorks® No-Clean Tacky Flux is ideally positioned between the more traditional RMA paste fluxes and the synthetic low residue-tacky fluxes. Typical RMA fluxes have strong activity but lack stability and consistency, whereas synthetic low-residue tacky fluxes are stable in their characteristics, but only sufficiently active for a limited range of soldering parameters. CircuitWorks® No-Clean Tacky Flux can be used in a wide range of soldering applications with predictable results. CircuitWorks® No-Clean Tacky Flux can be used for the following applications: BGA ball attachment and detachment; repair and rework of printed circuit board (PCB) components; and soldering of specialty components that cannot be attached in standard SMT reflow of PTH wave solder applications. -

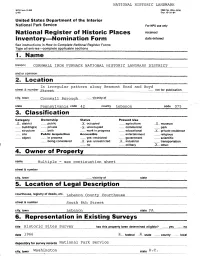

3. Classification 4. Owner of Property 5. Location of Legal Description 6

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (3-82) Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department of the interior National Park Semes For NPS use only Of received date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections historic CORNWALL IRON FURNACE NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK DISTRICT and or common In irregular pattern along Rexmont Road and Boyd street & number street_________ _ _______ __________________—— no* city, town Cornwall Borough ——vicinity of state Pennsylvania code 42 county Lebanon code 075 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use X district __ public X occupied agriculture _X_ museum building(s) private X unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress educational _X_ private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process yes: restricted government efiantifir being considered _X- yes: unrestricted X industrial transportation no military ...X other: 4. Owner of Property name Multiple - see continuation sheet street & number city, town __ vicinity of state 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. T.P hanon County Courthouse street & number South 8th Street city, town Lebanon state PA 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title Historic Sites Survey has this property been determined eligible? yes no date 1966 _ federal county local depository for survey records National Park Service city, town Washington state D.C. 7. Description Condition Check one Check one X excellent deteriorated unaltered XL original site good ruins _X_ altered moved date fair unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance The Cornwall Iron Furnace National Historic Landmark contains three interrelated major elements. -

Removal of Oxide Inclusions in Aluminium Scrap Casting Process with Sodium Based Fluxes

MATEC Web of Conferences 269, 07002 (2019) https://doi.org/10.1051/matecconf/201926907002 IIW 2018 Removal of Oxide Inclusions in Aluminium Scrap Casting Process with Sodium based Fluxes Widyantoro1, Donanta Dhaneswara1, Jaka Fajar Fatriansyah1, Muhammad Reza Firmansyah1, and Yus Prasetyo2 1Department of Metallurgical and Materials Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Universitas Indonesia, Kampus UI, Depok, Indonesia 16424 2Center for Materials Processing and Failure Analysis, Universitas Indonesia, Depok, Indonesia 16424 Abstract. The investigation of Oxide Inclusions removal in aluminium scrap casting process with sodium based fluxes has been carried out. The purpose of this research is to investigate the effect of Na2SO4 and NaCl based fluxes addition onto the fluidity and microstructure of aluminium product. The alloy which is used in this investigation is Al-Si which mixed with metal scrap using gravity casting method. The variation of melting temperature in this investigation are 700oC, 740oC, and 780oC. In this research, material characterization was determined using DSC, EDAX, XRD, and fluidity test. The results show that the number of oxide inclusions decrease as the addition of 0,2% wt. flux, and completly removed after the addition of 0,4% wt. flux. The highest fluidity and tensile strength was obtained after the addition of 0,4% wt. flux. at 7400C.. 1 Introduction Chemical components that are used in a flux depends on the objective of casting process (alkali removal, Aluminium alloys is widely applied in many industrial cleanliness, dross separation) [15]. In this paper flux product, such as transportation, packaging, construction, based Na2SO4 and NaCl was used to reduce the or houseware product due to its excellent properties, percentage of oxide inclusions inside the molten such as light weight, high corrosion resistance, high aluminium by binding the inclusions into the melt castability, and good conductor [1]-[4]. -

How Fluxes Determine the Metallurgical Properties of Submerged Arc Welds

Technical Note How Fluxes Determine the Metallurgical Properties of Submerged Arc Welds Dissolved oxygen, the deciding factor in determining impact properties—in particular the transition temperature- is controlled by the molten slag and its active components BY ir. J. H. PALM ABSTRACT. From metallurgical considera Acid, Neutral or Basic stability, speed capacity, shape and tions it is concluded that the dissolved In papers and lectures on welding appearance of the weld and slag de- O-content (and not the total O-content) tachability. This means that the concen of the weld metal very likely is the fluxes one nearly always finds the opin ion that the main factor governing the tration of the constituents must be decisive factor determining its impact restricted between certain limits. properties, especially its transition tem mechanical properties of weld metal, perature. especially its impact behavior, is ba In general, the flux constituents are The dissolved O-content depends on sicity. However, in general any accept oxides like MnO, SiO,, CaO, MgO, the O-potential of the surrounding active able explanation is missing. AI>03, Ti02 and Na-jO and fluorides medium. In submerged arc welding this Moreover, the authors fail in dis like CaF-2 and Na3AlF6. In the case of is the molten slag and its active com tinguishing between metallurgical and sintered or agglomerated fluxes they ponents; as far as O is concerned, this is chemical factors and in a certain sense a may also contain deoxidizers and alloy practically restricted to SiO;*. MnO and lack of understanding in this matter ing elements. -

Rheological Performance of Magnetorheological Grease with Embedded Graphite Additives

materials Article Rheological Performance of Magnetorheological Grease with Embedded Graphite Additives Nur Alyaa Mohd Nasir 1, Nurhazimah Nazmi 1,* , Norzilawati Mohamad 2 , Ubaidillah Ubaidillah 3 , Nur Azmah Nordin 1, Saiful Amri Mazlan 1, Siti Aishah Abdul Aziz 1 , Muhammad Kashfi Shabdin 4 and Nurul Azhani Yunus 5,* 1 Engineering Materials and Structures (eMast) iKohza, Malaysia-Japan International Institute of Technology (MJIIT), Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Jalan Sultan Yahya Petra, Kuala Lumpur 54100, Malaysia; [email protected] (N.A.M.N.); [email protected] (N.A.N.); [email protected] (S.A.M.); [email protected] (S.A.A.A.) 2 Faculty of Engineering, Universiti Malaysia Sabah, Jalan UMS, Kota Kinabalu 88400, Malaysia; [email protected] 3 Mechanical Engineering Department, Universitas Sebelas Maret, J1. Ir. Sutami 36A, Kentingan, Sukarta 57126, Indonesia; [email protected] 4 Department of Physics, Faculty of Science, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Serdang 43400, Malaysia; kashfi[email protected] 5 Mechanical Engineering Department, Universiti Teknologi PETRONAS, Seri Iskandar 32610, Malaysia * Correspondence: [email protected] (N.N.); [email protected] (N.A.Y.) Abstract: The use of highly viscous grease as a medium in magnetorheological grease (MRG) provides the benefit of avoiding sedimentation from occurring. However, it limits the expansion of Citation: Mohd Nasir, N.A.; Nazmi, yield stress in the on-state condition, thus reducing the application performance during operation. N.; Mohamad, N.; Ubaidillah, U.; Therefore, in this study, the improvement in the rheological properties of MRG was investigated Nordin, N.A.; Mazlan, S.A.; Abdul through the introduction of graphite as an additive. -

Making ^Anthracite Iron N the Eighteenth Century Charcoal Was the Principal Fuel Used for Smelting Iron

discovery of the ^Process for (^Making ^Anthracite Iron N THE eighteenth century charcoal was the principal fuel used for smelting iron. When in the course of time the demand for I iron increased and the hardwood forests used for making charcoal became smaller, ironmasters looked for other fuels. In Britain and continental Europe they turned to soft coal, which was generally located near deposits of iron ore and from which coke could be made. Anthracite deposits were more scarce. Only a few of the many blast furnaces in Europe—those located near the veins of anthracite—would benefit if a way could be found to use this "stone coal/' as anthracite was then commonly called.1 The situation in the United States was far different, with the development of an entire industry at stake. Deposits of bituminous coal lay for the most part beyond the mountains, far from the centers of population and the extant means of transportation. The iron-rich ridges and valleys of eastern Pennsylvania and New Jersey, however, lay near extensive fields of anthracite. The canals which penetrated into the anthracite regions in the second quarter of the nineteenth century linked cities, towns, and deposits of iron ore, limestone, and anthracite like beads on a chain, 1 The first description of the discovery of the anthracite process appeared in 1841 in the form of a book and may have helped to advertise the process among ironmasters: Walter R. Johnson, Notes on the Use of Anthracite in the Manufacture of Iron with Some Remarks on Its Evaporating Power (Boston, 1841).