Thematic Patterns in Millennial Heavy Metal: a Lyrical Analysis 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Cornell Alumni News Volume 49, Number 7 November 15, 1946 Price 20 Cents

Cornell Alumni News Volume 49, Number 7 November 15, 1946 Price 20 Cents Dawson Catches a Pass from Burns in Yale Game on Schoellkopf Field "It is not the finding of a thing, but the making something out of it after it is found, that is of consequence ' —JAMES RUSSELL LOWELL Why some things get better all the time TAKE THE MODERN ELECTRIC LIGHT BULB, for ex- Producing better materials for the use of industry ample. Its parts were born in heat as high as 6,000° F. and the benefit of mankind is the work of Union ... in cold as low as 300° below zero . under crush- Carbide. ing pressure as great as 3,000 pounds per square inch. Basic knowledge and persistent research are re- Only in these extremes of heat, cold and pressure quired, particularly in the fields of science and en- did nature yield the metal tungsten for the shining gineering. Working with extremes of heat and cold, filament. argon, the colorless gas that fills the bulb and with vacuums and great pressures, Units of UCC . and the plastic that permanently seals the glass now separate or combine nearly one-half of the many to the metal stem. And it is because elements of the earth. of such materials that light bulbs today are better than ever before. The steady improvement of the TTNION CARBIDE V-/ AND CARBON CORPORATION electric light bulb is another in- stance of history repeating itself. For man has always Products of Divisions and Units include— had to have better materials before he could make ALLOYS AND METALS CHEMICALS PLASTICS ELECTRODES, CARBONS, AND BATTERIES better things. -

Music Video As Black Art

IN FOCUS: Modes of Black Liquidity: Music Video as Black Art The Unruly Archives of Black Music Videos by ALESSANDRA RAENGO and LAUREN MCLEOD CRAMER, editors idway through Kahlil Joseph’s short fi lm Music Is My Mis- tress (2017), the cellist and singer Kelsey Lu turns to Ishmael Butler, a rapper and member of the hip-hop duo Shabazz Palaces, to ask a question. The dialogue is inaudible, but an intertitle appears on screen: “HER: Who is your favorite fi lm- Mmaker?” “HIM: Miles Davis.” This moment of Black audiovisual appreciation anticipates a conversation between Black popular cul- ture scholars Uri McMillan and Mark Anthony Neal that inspires the subtitle for this In Focus dossier: “Music Video as Black Art.”1 McMillan and Neal interpret the complexity of contemporary Black music video production as a “return” to its status as “art”— and specifi cally as Black art—that self-consciously uses visual and sonic citations from various realms of Black expressive culture in- cluding the visual and performing arts, fashion, design, and, obvi- ously, the rich history of Black music and Black music production. McMillan and Neal implicitly refer to an earlier, more recogniz- able moment in Black music video history, the mid-1990s and early 2000s, when Hype Williams defi ned music video aesthetics as one of the single most important innovators of the form. Although it is rarely addressed in the literature on music videos, the glare of the prolifi c fi lmmaker’s infl uence extends beyond his signature lumi- nous visual style; Williams distinguished the Black music video as a creative laboratory for a new generation of artists such as Arthur Jafa, Kahlil Joseph, Bradford Young, and Jenn Nkiru. -

Anal Cunt • Deceased • Executioner Fistula • Panzerbastard • Psycho Rampant Decay/Kruds • Rawhide Revilers • Slimy Cunt & the Fistfucks Strong Intention

PRESENTS RELEASES FROM: ANAL CUNT • DECEASED • EXECUTIONER FISTULA • PANZERBASTARD • PSYCHO RAMPANT DECAY/KRUDS • RAWHIDE REVILERS • SLIMY CUNT & THE FISTFUCKS STRONG INTENTION Now Exclusively Distributed by ANAL CUNT Street Date: Fuckin’ A, CD AVAILABLE NOW! INFORMATION: Artist Hometown: Boston, MA Key Markets: Boston, New York, Los Angeles, Portland OR For Fans of: GG ALLIN, NAPALM DEATH, VENOM, AGORAPHOBIC NOSEBLEED Fans of strippers, hard drugs, punk rock production and cock rock douchebaggery, rejoice: The one and only ANAL CUNT have returned with a new album, and this time around, they’re shooting to thrill –instead of just horrifically maim. They’re here to f*** your girlfriend, steal your drugs, piss in your whiskey, and above all, ROCK! (The late) Seth Putnam channels Sunset Strip scumbags like MOTLEY ARTIST: ANAL CUNT CRUE and TWISTED SISTER to bring you a rock’n’roll nightmare fueled TITLE: Fuckin’ A by their preferred cocktail of sex, violence, and unbridled disgust. From LABEL: PATAC ripping off theCRUE’s cover art to the massive hard rock riffs of “Hot Girls CAT#: PATAC-011 on the Road,” “Crankin’ My Band’s Demo on a Box at the Beach,” and “F*** FORMAT: CD YEAH!” and tender ballad “I Wish My Dealer Was Open,” Fuckin’ A is an GENRE: Metal instant scuzz rock classic. BOX LOT: 30 SRLP: $10.98 UPC: 628586220218 EXPORT: NO SALES TO THE UK Marketing Points: • 1ST PRESS LIMITED TO 1000 COPIES. Currently on its third pressing! • Final album before the passing of ANAL CUNT frontman Seth Putnam Tracklist: • Print ads in Maximumrocknroll, Decibel, Short Fast & Loud and Chips & Beer 1. -

TRUTH CORRODED BIOGRAPHY 2018 Drums: Jake Sproule, Vocals: Jason North, Guitar

TRUTH CORRODED BIOGRAPHY 2018 Drums: Jake Sproule, Vocals: Jason North, Guitar: Trent Simpson, Bass: Greg Shaw, Lead Guitar: Chris Walden TRUTH CORRODED are an Australian band with a sound that captures elements of late 80's/early 90's inspired thrash and death metal, shaped by the likes of bands such as SLAYER, OBITUARY, SEPULTURA, KREATOR and EXHORDER, and then later influenced by acts such as MISERY INDEX, BEHEMOTH, NEUROSIS, DECAPITATED and REVOCATION. Taken together the influences have shaped a sound that is as confronting as the subject matter of the bands lyrics and pays homage to the go for the throat savagery of the bands roots. TRUTH CORRODED signed with leading US extreme metal label UNIQUE LEADER RECORDS which led to the release of the album titled 'Bloodlands' which was released in March 2019. Based on themes surrounding war and displacement, the album depicts the state of our times and the social and political impact that is having both in the bands home country Australia and abroad. The title refers to the growth of new conflict from conflicts past, with the suffering it creates spreading its roots. The album was recorded with session drummer Kevin Talley (SUFFOCATION, DYING FETUS, CHIMAIRA) – his third album with the band – and was mixed and mastered by renowned heavy music producer Chris 'ZEUSS' Harris (HATEBREED, SOULFLY, REVOCATION). The album also features guest appearances by Stephen Carpenter of DEFTONES, Terrance Hobbs of SUFFOCATION, Mark Kloeppel of MISERY INDEX and Ryan Knight, ex-THE BLACK DAHLIA MURDER/ARSIS. Artwork for the album is designed by Gary Ronaldson at Bite Radius Designs (MISERY INDEX, BENIGHTED, PIG DESTROYER, THY ART IS MURDER) Commenting on the industry involved, vocalist Jason North offers "When we first set out to write the album we could not have imagined that we would work with the artists that have become involved. -

Trap Pilates POPUP

TRAP PILATES …Everything is Love "The Carters" June 2018 POP UP… Shhh I Do Trap Pilates DeJa- Vu INTR0 Beyonce & JayZ SUMMER Roll Ups….( Pelvic Curl | HipLifts) (Shoulder Bridge | Leg Lifts) The Carters APESHIT On Back..arms above head...lift up lifting right leg up lower slowly then lift left leg..alternating SLOWLY The Carters Into (ROWING) Fingers laced together going Side to Side then arms to ceiling REPEAT BOSS Scissors into Circles The Carters 713 Starting w/ Plank on hands…knee taps then lift booty & then Inhale all the way forward to your tippy toes The Carters exhale booty toward the ceiling….then keep booty up…TWERK shake booty Drunk in Love Lit & Wasted Beyonce & Jayz Crazy in Love Hands behind head...Lift Shoulders extend legs out and back into crunches then to the ceiling into Beyonce & JayZ crunches BLACK EFFECT Double Leg lifts The Carters FRIENDS Plank dips The Carters Top Off U Dance Jay Z, Beyonce, Future, DJ Khalid Upgrade You Squats....($$$MOVES) Beyonce & Jay-Z Legs apart feet plie out back straight squat down and up then pulses then lift and hold then lower lift heel one at a time then into frogy jumps keeping legs wide and touch floor with hands and jump back to top NICE DJ Bow into Legs Plie out Heel Raises The Carters 03'Bonnie & Clyde On all 4 toes (Push Up Prep Position) into Shoulder U Dance Beyonce & JayZ Repeat HEARD ABOUT US On Back then bend knees feet into mat...Hip lifts keeping booty off the mat..into doubles The Cartersl then walk feet ..out out in in.. -

Beyond the Black Are Most Certainly That. You're in Doubt?

Lost in Forever - LIVE Stratospheric? Beyond The Black are most certainly that. You’re in doubt? Let’s explain… …Only two years ago, dynamic frontwoman and world-class vocalist Jennifer Haben and her band colleagues celebrated their live debut on stage at the legendary Wacken Open Air 2014. A few months later they were supporting the legendary SAXON on their UK tour. On February 13th 2015 the band released their debut full-length album Songs of Love and Death, which hit the German top 20 album charts, and which was produced by melodic metal maestro Sascha Paeth (Avantasia, Edguy, Epica, Kamelot, Rhapsody). You’ve probably already guessed that the album was royally received throughout Europe, with Haben establishing herself as one of the leading voices in hard rock and metal music. Beyond The Black continued to conquer the road. They played their own headliner tour in spring and autumn 2015, and featured at several of Germany’s biggest rock & metal- festivals. Momentum is beautiful thing; Beyond The Black supported Queensrÿche in Holland and Within Temptation in Switzerland, and their incredible ascent culminated in them receiving the “Best Debut Album 2015” Metal Hammer Award. MANAGEMENT: BOOKING WORLDWIDE: MPS Hanseatic UG International Talent Booking Thomas Jensen & Leo Loers Olivia Sime Neuer Kamp 32 6th Floor | 9 Kingsway 20357 Hamburg London | WC2B 6XF | UK Mail: [email protected] Mail: [email protected] Enough for the year? Hardly. Because between all that stuff, they were working on their second full-length album “Lost in Forever”, which was released in February 2016 (G/A/S), entered the German charts at #4 and will soon enjoy a worldwide release. -

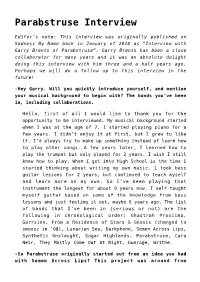

Parabstruse Interview

Parabstruse Interview Editor’s note: This interview was originally published on Sadness By Name back in January of 2010 as “Interview with Garry Brents of Parabstruse”. Garry Brents has been a close collaborator for many years and it was an absolute delight doing this interview with him three and a half years ago. Perhaps we will do a follow up to this interview in the future! -Hey Garry. Will you quickly introduce yourself, and mention your musical background to begin with? The bands you’ve been in, including collaborations. Hello, first of all I would like to thank you for the opportunity to be interviewed. My musical background started when I was at the age of 7. I started playing piano for a few years. I didn’t enjoy it at first, but I grew to like it. I’d always try to make up something instead of learn how to play other songs. A few years later, I learned how to play the trumpet but only played for 2 years. I wish I still knew how to play. When I got into High School is the time I started thinking about writing my own music. I took bass guitar lessons for 2 years, but continued to teach myself and learn more on my own. So I’ve been playing that instrument the longest for about 9 years now. I self-taught myself guitar based on some of the knowledge from bass lessons and just feeling it out, maybe 6 years ago. The list of bands that I’ve been in (serious or not) are the following in chronological order: Ghastrah Proxiima, Garrsinn, From a Residence of Stars & Gnosis (changed to smoosz in ’08), Lunarian Sea, Darkphone, Semen Across Lips, Synthetic Onslaught, Sugar Highlands, Parabstruse, Cara Neir, They Mostly Come Out At Night, bunrage, Writhe. -

Metaldata: Heavy Metal Scholarship in the Music Department and The

Dr. Sonia Archer-Capuzzo Dr. Guy Capuzzo . Growing respect in scholarly and music communities . Interdisciplinary . Music theory . Sociology . Music History . Ethnomusicology . Cultural studies . Religious studies . Psychology . “A term used since the early 1970s to designate a subgenre of hard rock music…. During the 1960s, British hard rock bands and the American guitarist Jimi Hendrix developed a more distorted guitar sound and heavier drums and bass that led to a separation of heavy metal from other blues-based rock. Albums by Led Zeppelin, Black Sabbath and Deep Purple in 1970 codified the new genre, which was marked by distorted guitar ‘power chords’, heavy riffs, wailing vocals and virtuosic solos by guitarists and drummers. During the 1970s performers such as AC/DC, Judas Priest, Kiss and Alice Cooper toured incessantly with elaborate stage shows, building a fan base for an internationally-successful style.” (Grove Music Online, “Heavy metal”) . “Heavy metal fans became known as ‘headbangers’ on account of the vigorous nodding motions that sometimes mark their appreciation of the music.” (Grove Music Online, “Heavy metal”) . Multiple sub-genres . What’s the difference between speed metal and death metal, and does anyone really care? (The answer is YES!) . Collection development . Are there standard things every library should have?? . Cataloging . The standard difficulties with cataloging popular music . Reference . Do people even know you have this stuff? . And what did this person just ask me? . Library of Congress added first heavy metal recording for preservation March 2016: Master of Puppets . Library of Congress: search for “heavy metal music” April 2017 . 176 print resources - 25 published 1980s, 25 published 1990s, 125+ published 2000s . -

EPICA „Requiem for the Indifferent“

EPICA „Requiem For The Indifferent“ VÖ: 09.03.2012 Line up: Epica Online: Simone Simons – Vocals www.epica.nl Mark Jansen – Guitars & Vocals www.facebook.com/epica Coen Janssen – Synths & Piano Isaac Delahaye - Guitars Arien van Weesenbeek – Drums Yves Huts - Bass Ever since EPICA emerged on the scene at the end of 2002, the band has been living in a whirlwind of studio recordings, interviews, screaming fans, live performances and a rock 'n roll lifestyle. With every new album EPICA pushes the boundaries by reinventing their distinctive style, and nothing seems to stop the band on their rise to the top. With their previous record ‘Design Your Universe’, seen by many as a true milestone in bombastic and symphonic metal, EPICA seemed to have found the perfect musical mixture between classical and heavy music. The album entered the charts everywhere and consolidated their position among the top of today’s metal acts. An extensive tour marathon with over 200 headlining shows allover the globe proved both their ambition and their success. This time EPICA once again raises the bar with their fifth album called 'Requiem of the Indifferent’. Full of trademark hymns, significant lyrics, powerful guitar riffing alternated with cinematic interludes, Simone Simons’ angelic voice, it is a very logical step after ‘Design Your Universe’. Again it is an album which has to grow on the listener, so make sure to give it a couple of spins to get the whole picture. As with every album, EPICA mixes hard, technical and fast with intimate and slow, with as good as everything in between. -

Thematic Patterns in Millennial Heavy Metal: a Lyrical Analysis

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2012 Thematic Patterns In Millennial Heavy Metal: A Lyrical Analysis Evan Chabot University of Central Florida Part of the Sociology Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Chabot, Evan, "Thematic Patterns In Millennial Heavy Metal: A Lyrical Analysis" (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 2277. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/2277 THEMATIC PATTERNS IN MILLENNIAL HEAVY METAL: A LYRICAL ANALYSIS by EVAN CHABOT B.A. University of Florida, 2011 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Sociology in the College of Sciences at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2012 ABSTRACT Research on heavy metal music has traditionally been framed by deviant characterizations, effects on audiences, and the validity of criticism. More recently, studies have neglected content analysis due to perceived homogeneity in themes, despite evidence that the modern genre is distinct from its past. As lyrical patterns are strong markers of genre, this study attempts to characterize heavy metal in the 21st century by analyzing lyrics for specific themes and perspectives. Citing evidence that the “Millennial” generation confers significant developments to popular culture, the contemporary genre is termed “Millennial heavy metal” throughout, and the study is framed accordingly. -

AGALLOCH and ANAAL NATHRAKH at the INFERNO FESTIVAL 2012!

AGALLOCH and ANAAL NATHRAKH at the INFERNO FESTIVAL 2012! The american avant garde folk metal band AGALLOCH and Britains most necro black metal band ANAAL NATHRAKH are the next band on the bill for the INFERNO festival 2012. Together with the legendary BORKANAGAR, ARCTURUS and WITCHERY the 2012 edition of the INFERNO METAL FESTIVAL will be extreme. The countdown to the true black easter has begun - Get ready for four unholy days - and a hell of lot of bands! THE INFERNO METAL FESTIVAL has become a true black Easter tradition for metal fans, bands and music industry from all over the world with nearly 50 concerts every year since the start back in 2001. The festival offers exclusive concerts in unique surroundings with some of the best extreme metal bands and experimental artists in the world, from the new and underground to the legendary giants. At INFERNO you meet up with fellow metalheads for four days of head banging, party, black- metal sightseeing and expos, horror films, art exhibitions and all the unholy treats your dark heart desires. THE INFERNO METAL FESTIVAL invites you all to the annual black Easter gathering of metal, gore and extreme in Oslo, Norway from April 4. -7.april 2011. - Four days and a hell of a lot of bands! AGALLOCH: Agalloch is an American metal band formed in 1995 in Portland, Oregon. The band is led by vocalist and guitarist John Haughm and so far have released four limited EPs, four full-length albums. Inspired from bandS like ULVER and KATATONIA, Agalloch performs a progressive and avant-garde style of folk metal that encompasses an eclectic range of tendencies including neofolk, post-rock, black metal and doom metal.