The Future of the CEMAC CFA Franc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

June 2021 Indices Des Prix De Détail Relatif Aux Dépenses De La Vie Courante Des Fonctionnaires De L'onu New York = 100, Date D'indice = Juin 2021

Price indices Indices des prix Retail price indices relating to living expenditures of United Nations Officials New York City = 100, Index date = June 2021 Indices des prix de détail relatif aux dépenses de la vie courante des fonctionnaires de l'ONU New York = 100, Date d'indice = Juin 2021 National currency per US $ Index - Indice Monnaie nationale du $ E.U. Excluding Country or Area Duty Station housing 2 Pays ou Zone Villes-postes Per US$ 1 Currency Total Non compris 1 Cours du $E-U Monnaie l'habitation 2 Afghanistan Kabul 78.070 Afghani 86 93 Albania - Albanie Tirana 98.480 Lek 78 82 Algeria - Algérie Algiers 132.977 Algerian dinar 80 85 Angola Luanda 643.121 Kwanza 84 93 Argentina - Argentine Buenos Aires 94.517 Argentine peso 81 84 Armenia - Arménie Yerevan 518.300 Dram 75 80 Australia - Australie Sydney 1.291 Australian dollar 82 88 Austria - Autriche Vienna 0.820 Euro 91 100 Azerbaijan - Azerbaïdjan Baku 1.695 Azerbaijan manat 81 87 Bahamas Nassau 1.000 Bahamian dollar 100 96 Bahrain - Bahreïn Manama 0.377 Bahraini dinar 83 86 Bangladesh Dhaka 84.735 Taka 81 89 Barbados - Barbade Bridgetown 2.000 Barbados dollar 90 95 Belarus - Bélarus Minsk 2.524 New Belarusian ruble 85 91 Belgium - Belgique Brussels 0.820 Euro 84 92 Belize Belmopan 2.000 Belize dollar 76 80 Benin - Bénin Cotonou 537.714 CFA franc 83 92 Bhutan - Bhoutan Thimpu 72.580 Ngultrum 77 83 Bolivia (Plurinational State of) - Bolivie (État plurinational de) La Paz 6.848 Boliviano 73 80 Bosnia and Herzegovina - Bosnie-Herzégovine Sarajevo 1.603 Convertible mark 73 79 Botswana Gaborone 10.582 Pula 75 83 Brazil - Brésil Brasilia 5.295 Real 71 82 British Virgin Islands - Îles Vierges britanniques Road Town 1.000 US dollar 87 93 Bulgaria - Bulgarie Sofia 1.603 Lev 70 85 Burkina Faso Ouagadougou 537.714 CFA franc 80 87 Burundi Bujumbura 1,953.863 Burundi franc 82 90 Cabo Verde - Cap-Vert Praia 90.389 CV escudo 79 87 Cambodia - Cambodge Phnom Penh 4,098.000 Riel 82 88 Cameroon - Cameroun Yaounde 537.714 CFA franc 83 91 Canada Montreal 1.208 Canadian dollar 91 96 Central African Rep. -

Towards a More United & Prosperous Union of Comoros

TOWARDS A MORE UNITED & PROSPEROUS Public Disclosure Authorized UNION OF COMOROS Systematic Country Diagnostic Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized ABBREVIATIONS & ACRONYMS i CPIA Country Policy and Institutional Assessment CSOs Civil Society Organizations DeMPA Debt Management Performance Assessment DPO Development Policy Operation ECP Economic Citizenship Program EEZ Exclusive Economic Zone EU European Union FDI Foreign Direct Investment GDP Gross Domestic Product GNI Gross National Income HCI Human Capital Index HDI Human Development Index ICT Information and Communication Technologies IDA International Development Association IFC International Finance Corporation IMF International Monetary Fund INRAPE National Institute for Research on Agriculture, Fisheries, and the Environment LICs Low-income Countries MDGs Millennium Development Goals MIDA Migration for Development in Africa MSME Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises NGOs Non-profit Organizations PEFA Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability PPP Public/Private Partnerships R&D Research and Development SADC Southern African Development Community SDGs Sustainable Development Goals SOEs State-Owned Enterprises SSA Sub-Saharan Africa TFP Total Factor Productivity WDI World Development Indicators WTTC World Travel & Tourism Council ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to thank members of the Comoros Country Team from all Global Practices of the World Bank and the International Finance Corporation, as well as the many stakeholders in Comoros (government authorities, think tanks, academia, and civil society organizations, other development partners), who have contributed to the preparation of this document in a strong collaborative process (see Annex 1). We are grateful for their inputs, knowledge and advice. This report has been prepared by a team led by Carolin Geginat (Program Leader EFI, AFSC2) and Jose Luis Diaz Sanchez (Country Economist, GMTA4). -

The CFA Franc Zone

banque monnaie comprendre euro stabilité connaître économie l’éco en bref The CFA franc zone KEY FACTS KEY FIGURES The CFA franc zone is an economic and monetary area bringing together France and 15 countries 16 3 in Sub-Saharan Africa. This area is built on an countries currencies institutional framework and a fixed exchange rate. including France and pegged to the euro The CFA franc zone thus fosters economic growth 15 Sub-Saharan African countries and monetary and financial stability. The CFA franc zone is an instrument of solidarity and development based on three principles of monetary cooperation: • pegging of the three African currencies to the euro since 1999, to ensure their stability. They were previously pegged to the French franc; 7.2% • a guarantee of unlimited convertibility of the three GDP growth currencies by the French Treasury; 2016 forecast for the WAEMU 155 • in return for this guarantee, foreign exchange from the Central Bank million of West African States (BCEAO) residents in the African states reserves are centralised by the African states in (2.0% for the CEMAC of the CFA franc zone their central banks, which are required to deposit at according to the Bank least half (100% for Comoros) of these assets with of Central African States (BEAC)) the French Treasury, in a current account. Three economic regions make up the CFA franc zone in Africa, each with its own currency: • the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU) where the CFA franc (Communauté Financière Africaine, XOF) is used by Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Mali, Niger, Senegal, Togo and Guinea Bissau. -

The Franc Zone

The franc zone The franc zone is an economic, monetary and cultural area that is equivalent to none other in the world. It is made up of very diverse states and territories and results from developments and changes in the former French colonial empire. After attaining their independence, most of the newly-created African states decided to remain within a homogenous group characterised by a new institutional framework and a common exchange rate mechanism. Fact Sheet The franc zone is made up of France and 15 African states: Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea Bissau, Mali, Niger, Senegal and Togo in West Africa, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Congo, Equatorial Guinea and Gabon in Central Africa, and the Comoros. The franc zone is a rare example of close institutionalised cooperation between countries from two continents that share a common language and history. The Banque de France has developed close ties with the franc zone central banks, with which it works towards ensuring the smooth functioning of the area’s shared institutions. This Fact Sheet describes the franc zone’s institutional structures and the changes they are undergoing, and brings to the fore the franc zone countries’ determination to forge ahead with regional integration in order to support growth and reduce poverty. The franc zone annual report provides detailed information on the eco- nomic and financial situation of the franc zone. It is published by the Banque de France and available on its website www.banque-france.fr n° 127 April 2002 updated July 2010 Communication Directorate 1. HISTORY OF THE FRANC ZONE 1.1. -

List of Currencies of All Countries

The CSS Point List Of Currencies Of All Countries Country Currency ISO-4217 A Afghanistan Afghan afghani AFN Albania Albanian lek ALL Algeria Algerian dinar DZD Andorra European euro EUR Angola Angolan kwanza AOA Anguilla East Caribbean dollar XCD Antigua and Barbuda East Caribbean dollar XCD Argentina Argentine peso ARS Armenia Armenian dram AMD Aruba Aruban florin AWG Australia Australian dollar AUD Austria European euro EUR Azerbaijan Azerbaijani manat AZN B Bahamas Bahamian dollar BSD Bahrain Bahraini dinar BHD Bangladesh Bangladeshi taka BDT Barbados Barbadian dollar BBD Belarus Belarusian ruble BYR Belgium European euro EUR Belize Belize dollar BZD Benin West African CFA franc XOF Bhutan Bhutanese ngultrum BTN Bolivia Bolivian boliviano BOB Bosnia-Herzegovina Bosnia and Herzegovina konvertibilna marka BAM Botswana Botswana pula BWP 1 www.thecsspoint.com www.facebook.com/thecsspointOfficial The CSS Point Brazil Brazilian real BRL Brunei Brunei dollar BND Bulgaria Bulgarian lev BGN Burkina Faso West African CFA franc XOF Burundi Burundi franc BIF C Cambodia Cambodian riel KHR Cameroon Central African CFA franc XAF Canada Canadian dollar CAD Cape Verde Cape Verdean escudo CVE Cayman Islands Cayman Islands dollar KYD Central African Republic Central African CFA franc XAF Chad Central African CFA franc XAF Chile Chilean peso CLP China Chinese renminbi CNY Colombia Colombian peso COP Comoros Comorian franc KMF Congo Central African CFA franc XAF Congo, Democratic Republic Congolese franc CDF Costa Rica Costa Rican colon CRC Côte d'Ivoire West African CFA franc XOF Croatia Croatian kuna HRK Cuba Cuban peso CUC Cyprus European euro EUR Czech Republic Czech koruna CZK D Denmark Danish krone DKK Djibouti Djiboutian franc DJF Dominica East Caribbean dollar XCD 2 www.thecsspoint.com www.facebook.com/thecsspointOfficial The CSS Point Dominican Republic Dominican peso DOP E East Timor uses the U.S. -

The Case of the CFA Franc in West Africa

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Koddenbrock, Kai; Sylla, Ndongo Samba Working Paper Towards a political economy of monetary dependency: The case of the CFA franc in West Africa MaxPo Discussion Paper, No. 19/2 Provided in Cooperation with: Max Planck Sciences Po Center on Coping with Instability in Market Societies (MaxPo) Suggested Citation: Koddenbrock, Kai; Sylla, Ndongo Samba (2019) : Towards a political economy of monetary dependency: The case of the CFA franc in West Africa, MaxPo Discussion Paper, No. 19/2, Max Planck Sciences Po Center on Coping with Instability in Market Societies (MaxPo), Paris This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/202323 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. -

BIS Locational Banking Statistics: Notes to Explain the Data Structure

Version DSD_LBS_V201712 December 2017 BIS locational banking statistics: explanation of the data structure definitions Contents 1. DSD for reporting: BIS_LBP ........................................................................................... 2 2. Code lists for selected dimensions.................................................................................. 4 2.1. Currency denomination: L_DENOM ...................................................................... 4 2.2. Currency type of reporting country: L_CURR_TYPE ............................................. 6 2.3. Parent country: L_PARENT_CTY .......................................................................... 7 2.4. Reporting country: L_REP_CTY ............................................................................ 9 2.5 Counterparty country dimension: L_CP_COUNTRY ........................................... 11 3. Consistency in reporting ............................................................................................... 18 3.1 Aggregates vs unallocated members .................................................................. 18 3.2 Instrument breakdown ......................................................................................... 18 3.3 Debt securities liabilities ...................................................................................... 18 3.4 Related offices and central banks ........................................................................ 19 3.5 Unrelated banks .................................................................................................. -

Currencies of the World

The World Trade Press Guide to Currencies of the World Currency, Sub-Currency & Symbol Tables by Country, Currency, ISO Alpha Code, and ISO Numeric Code € € € € ¥ ¥ ¥ ¥ $ $ $ $ £ £ £ £ Professional Industry Report 2 World Trade Press Currencies and Sub-Currencies Guide to Currencies and Sub-Currencies of the World of the World World Trade Press Ta b l e o f C o n t e n t s 800 Lindberg Lane, Suite 190 Petaluma, California 94952 USA Tel: +1 (707) 778-1124 x 3 Introduction . 3 Fax: +1 (707) 778-1329 Currencies of the World www.WorldTradePress.com BY COUNTRY . 4 [email protected] Currencies of the World Copyright Notice BY CURRENCY . 12 World Trade Press Guide to Currencies and Sub-Currencies Currencies of the World of the World © Copyright 2000-2008 by World Trade Press. BY ISO ALPHA CODE . 20 All Rights Reserved. Reproduction or translation of any part of this work without the express written permission of the Currencies of the World copyright holder is unlawful. Requests for permissions and/or BY ISO NUMERIC CODE . 28 translation or electronic rights should be addressed to “Pub- lisher” at the above address. Additional Copyright Notice(s) All illustrations in this guide were custom developed by, and are proprietary to, World Trade Press. World Trade Press Web URLs www.WorldTradePress.com (main Website: world-class books, maps, reports, and e-con- tent for international trade and logistics) www.BestCountryReports.com (world’s most comprehensive downloadable reports on cul- ture, communications, travel, business, trade, marketing, -

Use of Euro in Affiliated Countries and Territories Outside the EU

79 Use of Euro in Affiliated Countries and Territories Outside the EU Niels C. Andersen, Legal Affairs, and Niels Bartholdy, International Relations INTRODUCTION If Denmark's adoption of the euro is endorsed by the referendum in Denmark on 28 September 2000 it will be necessary to consider the cur- rency arrangements for the Faroe Islands and Greenland. Today they both use the Danish krone as their currency1. The Faroe Islands and Greenland are part of the Kingdom of Denmark, but are not members of the EU. Some of the present euro area member states have close economic relations with small states or territories which by tradition have used the present euro area member state's currency (e.g. the French franc) as their currency, but which are not members of the EU. The framework for the foreign-exchange cooperation between the euro area member states and these small states and territories after the introduction of the euro is set out in a number of EU decisions which are outlined in the following. A common feature of the EU decisions is that all of the small states and territories in question will have the opportunity to preserve the currency association to the euro area member state by using the euro as their currency. There is every indication that they will avail of this oppor- tunity. However, the more detailed legal arrangements between the individual euro area member states and the associated small states and territories remain to be clarified. Finally, the article describes two EU decisions on the currency relations between France and the CFA zone and the Comoro Islands, and Portugal and Cape Verde after the two EU member states' introduction of the euro. -

Ravi G Country Editor

Healing Initiative Leadership Linkage (HILL) Student Magazine: Country Name - Comoros World without Borders Monthly update: <Date> Current News Host Editor: Ravi G Country Editor: The Comoros is a volcanic At 1,660 km2 (640 sq mi), excluding the archipelago off Africa’s east coast, in contested island of Mayotte, the Comoros is the I the warm Indian Ocean waters of the third-smallest African nation by area. The Mozambique Channel. The nation population, excluding Mayotte, is estimated at state’s largest island, Grande Comore 795,601. As a nation formed at a crossroads of (Ngazidja) is ringed by beaches and different civilisations, the archipelago is noted old lava from active Mt. Karthala for its diverse culture and history. The volcano. Around the port and medina archipelago was first inhabited by Bantu in the capital, Moroni, are carved speakers who came from East Africa, doors and a white colonnaded supplemented by Arab and Austronesian mosque, the Ancienne Mosquée du immigration. Vendredi, recalling the islands’ Arab heritage. Music Art Sports Music of the Comoros. ... Zanzibar's Comorian Graffiti artist Popular sports of Comoros taarab music, however, remains the most and muralist Socrome ● Football (Soccer) influential genre on the islands, and a uses his art to illuminate ● basketball. Comorian version called twarab is his country's rich and ● track and field. popular. Leading twarab bands include diverse origins. ... The ● tennis. Sambeco and Belle Lumière, as well as archipelago is made up of ● swimming. singers including Chamsia Sagaf. four islands: Grande ● cycling. Comore, Anjouan, Mohéli and Mayotte. Previously a French colony, Mayotte is the only island that is still not independent Youth Excellence & Leader: What is catching the attention of your youth? While Comoros has no youth policy, a National youth day was held on 13 June 2013 as described on the official site of the comoros government. -

Monthly Currency Rates / Taux Mensuels Des

MONTHLY CURRENCY RATES / TAUX MENSUELS DES MONNAIES Exchange rates on 31 OCTOBER 2011 / Taux de change au 31 OCTOBRE 2011 APPLICABLE FOR THE MONTH OF NOVEMBER 2011 / APPLICABLE POUR LE MOIS DE NOVEMBRE2011 REGIONAL COUNTRIES / PAYS REGIONAUX COUNTRY / PAYS CURRENCY / RATE PER UA/ MONNAIES TAUX PAR RAPPORT A L'UC ALGERIA/ALGERIE DZD ALGERIAN DINAR 115,831 ANGOLA AON KWANZA 147,881 BOTSWANA BWP PULA 11,4012 BURUNDI BIF FRANC 2026,35 CAPE VERDE/CAP VERT CVE ESCUDO 127,527 CFA COUNTRIES/PAYS CFA XAF FRANC CFA 743,009 CFA COUNTRIES/PAYS CFA XOF FRANC CFA 743,009 COMOROS/COMORES KMF COMORIAN FRANC 557,257 CONGO DEM REP/REP DEM CONGO CDF Congo Franc 1439,02 DJIBOUTI DJF DJIBOUTI FRANC 277,533 EGYPT/EGYPTE EGP POUND 9,49806 ERITREA/ERYTHREE ERN ERITREA NAKFA 24,0099 ETHIOPIA/ETHIOPIE ETB BIRR 26,6778 GAMBIA/GAMBIE GMD DALASI 46,8132 GHANA GHS CEDI 2,43078 GUINEA/GUINEE GNF FRANC 10788,1 KENYA KES SHILLING 155,899 LESOTHO LSL MALOTI 12,4176 LIBERIA LRD LIBERIAN DOLLA 114,185 LIBYA/LIBYE LYD LYBIAN DINAR 1,93240 MADAGASCAR MGA ARIARY 3233,58 MALAWI MWK KWACHA 259,182 MAURITANIA/MAURITANIE MRO OUGUIYA 439,372 MAURITIUS/I.MAURICE MUR RUPEE 45,6238 MOROCCO/MAROC MAD DIRHAM 12,6388 MOZAMBIQUE MZN METICAIS 43,6458 NAMIBIA/NAMIBIE NAD NAMIBIAN DOLLA 12,4176 NIGERIA NGN NAIRA 240,646 RWANDA RWF RWANDA FRANC 936,948 SAO TOME & PRINCIPE/ STD DOBRA 28334,2 SEYCHELLES SCR RUPEE 19,5512 SIERRA LEONE SLL LEONE 7088,89 SOMALIA/SOMALIE SOS SHILLING 2577,09 SOUTH AFRICA/AFRIQUE DU SUD ZAR RAND 12,4176 SWAZILAND SZL LILANGENI 12,4176 TANZANIA/TANZANIE TZS SHILLING -

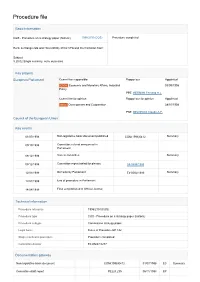

Procedure File

Procedure file Basic information COS - Procedure on a strategy paper (historic) 1998/2151(COS) Procedure completed Euro: exchange rate and convertibility of the CFA and the Comorian franc Subject 5.20.02 Single currency, euro, euro area Key players European Parliament Committee responsible Rapporteur Appointed ECON Economic and Monetary Affairs, Industrial 03/09/1998 Policy PPE HERMAN Fernand H.J. Committee for opinion Rapporteur for opinion Appointed DEVE Development and Cooperation 28/10/1998 PSE DELCROIX Claude A.F. Council of the European Union Key events 01/07/1998 Non-legislative basic document published COM(1998)0412 Summary 09/10/1998 Committee referral announced in Parliament 08/12/1998 Vote in committee Summary 08/12/1998 Committee report tabled for plenary A4-0484/1998 12/01/1999 Decision by Parliament T4-0002/1999 Summary 12/01/1999 End of procedure in Parliament 14/04/1999 Final act published in Official Journal Technical information Procedure reference 1998/2151(COS) Procedure type COS - Procedure on a strategy paper (historic) Procedure subtype Commission strategy paper Legal basis Rules of Procedure EP 142 Stage reached in procedure Procedure completed Committee dossier ECON/4/10277 Documentation gateway Non-legislative basic document COM(1998)0412 01/07/1998 EC Summary Committee draft report PE228.235 06/11/1998 EP Committee opinion DEVE PE228.201/DEF 02/12/1998 EP Committee report tabled for plenary, single A4-0484/1998 08/12/1998 EP reading OJ C 104 14.04.1999, p. 0004 Text adopted by Parliament, single reading T4-0002/1999 12/01/1999 EP Summary OJ C 104 14.04.1999, p.