Towards a Feminist Theory of Violence Monica Pa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The University of Chicago Looking at Cartoons

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO LOOKING AT CARTOONS: THE ART, LABOR, AND TECHNOLOGY OF AMERICAN CEL ANIMATION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF CINEMA AND MEDIA STUDIES BY HANNAH MAITLAND FRANK CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2016 FOR MY FAMILY IN MEMORY OF MY FATHER Apparently he had examined them patiently picture by picture and imagined that they would be screened in the same way, failing at that time to grasp the principle of the cinematograph. —Flann O’Brien CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES...............................................................................................................................v ABSTRACT.......................................................................................................................................vii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS....................................................................................................................viii INTRODUCTION LOOKING AT LABOR......................................................................................1 CHAPTER 1 ANIMATION AND MONTAGE; or, Photographic Records of Documents...................................................22 CHAPTER 2 A VIEW OF THE WORLD Toward a Photographic Theory of Cel Animation ...................................72 CHAPTER 3 PARS PRO TOTO Character Animation and the Work of the Anonymous Artist................121 CHAPTER 4 THE MULTIPLICATION OF TRACES Xerographic Reproduction and One Hundred and One Dalmatians.......174 -

Homicide Studies: Ten Years After Its Inception

Homicide Studies: Ten Years After Its Inception Proceedings of the 2007 Homicide Research Working Group Annual Symposium Minneapolis, Minnesota June 7-10 Edited by Katharina Gruenberg Lancaster University And C. Gabrielle Salfati John Jay College of Criminal Justice 1 Acknowledgements 2 The Homicide Research Working Group (HRWG) is an international and interdisciplinary organization of volunteers dedicated to cooperation among researchers and practitioners who are trying to understand and limit lethal violence. The HRWG has the following goals: to forge links between research, epidemiology and practical programs to reduce levels of mortality from violence; to promote improved data quality and the linking of diverse homicide data sources; to foster collaborative, interdisciplinary research on lethal and non-lethal violence; to encourage more efficient sharing of techniques for measuring and analyzing homicide; to create and maintain a communication network among those collecting, maintaining and analyzing homicide data sets; and to generate a stronger working relationship among homicide researchers. Homicide Research Working Group publications, which include the Proceedings of each annual Intensive Workshop (beginning in 1992), the HRWG Newsletter, and the contents of issues of the journal Homicide Studies (beginning in 1997), may be downloaded from the HRWG web site, which is maintained by the Inter-University Consortium of Political and Social Research, at the following address: http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/HRWG/ Suggested citation: Lin Huff-Corzine Katharina Gruenberg, Gabrielle Salfati (Eds.) (2007). Homicide Studies: Ten Years After Its Inception. Proceedings of the 2007 Meeting of the Homicide Research Working Group. Minneapolis, MN : Homicide Research Working Group. The views expressed in these Proceedings are those of the authors and speakers, and not necessarily those of the Homicide Research Working Group or the editor of this volume. -

Lynn Crosbie Fonds (F0691)

York University Archives & Special Collections (CTASC) Finding Aid - Lynn Crosbie fonds (F0691) Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.4.1 Printed: September 13, 2019 Language of description: English York University Archives & Special Collections (CTASC) 305 Scott Library, 4700 Keele Street, York University Toronto Ontario Canada M3J 1P3 Telephone: 416-736-5442 Fax: 416-650-8039 Email: [email protected] http://www.library.yorku.ca/ccm/ArchivesSpecialCollections/index.htm https://atom.library.yorku.ca//index.php/lynn-crosbie-fonds Lynn Crosbie fonds Table of contents Summary information .................................................................................................................................... 19 Administrative history / Biographical sketch ................................................................................................ 19 Scope and content ......................................................................................................................................... 20 Arrangement .................................................................................................................................................. 20 Notes .............................................................................................................................................................. 20 Access points ................................................................................................................................................. 21 Collection holdings ....................................................................................................................................... -

'Enigma Woman'

'EnigmaWoman' Nelli Madi|son Femme Fatales o Kathleen Cairns 4 gCN ir Fiction by In 1934 NellieMadison was arrestedfor the murderof her as an "ortlaw"to a public captivatedby such criminals as "BabyFace" Nelson, Clyde Barrow,and Bonnie Parker. Hereshe is seated at the counseltable during her trial in LosAngeles Superior Court. This content downloaded from 150.131.192.151 on Mon, 18 Nov 2013 02:22:14 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions hortly before midnight on March 24, 1934, Nellie Madison, a Montana rancher's daughter, pumped five bullets into her husband Eric as he lay in bed in the couple's Burbank, California, apartment. Police arrested her two days later hiding in the closet of a remote mountain cabin and brought her back to Burbank where she was questioned,jailed, and charged with first-degree murder. The case quickly became a media sensation. Reporters-fifty sat in on her interrogation-nick- named her the "enigmawoman" for her oddly detached and inscrutabledemeanor and her refusal to talk. Two months later,justbefore the startof her trial,Los Angeles County District Attorney Buron Fitts announced that he would seek the death penalty. To that date no woman had been executed in California,and only one woman, Emma LeDoux, had been condemned, in 1906, also for killing her husband. The state supreme court overturned LeDoux's sentence, but she still resided in prison in 1934.1 In the years between LeDoux's conviction and Madison's trial,California saw its share of notorious femalemurder defendants.Jurors gave Louise Peete a life sentence in 1920 after she killed her landlord and buried his body beneath his house. -

American Female Executions 1900 - 2021

American female executions 1900 - 2021. A total of 56 women have been lawfully executed in 20 states of the USA between 1903 and January 2021, including three under Federal Authority. 55 of them died for first degree murder or conspiracy to first degree murder and one for espionage. 39 executions took place between 1903 and 1962 and a further 14 since the resumption of the death penalty in 1976, between 1984 and 2014. Shellie McKeithen (executed January 1946) is erroneously included in some lists, but Shellie was male, despite his first name. 25 of these women died in the electric chair, 15 by lethal injection, 9 by hanging and 7 by lethal gas. 1) Thirty eight year old Dora Wright (black) became the first woman to be executed in the 20th century when she was hanged in Indian Territory at South McAllister, in what would become Oklahoma, on July 17, 1903. She was executed for the murder of 7 year old Annie Williams who is thought to have been her step daughter. Dora had beaten and tortured Annie repeatedly over a period of several months before finally killing her on February 2, 1903. According to a local newspaper it was “the most horrible and outrageous” crime in memory in the area. On May 29, 1903 the jury took just 20 minutes’ deliberation to reach a guilty verdict, but were divided upon the sentence, with three voting for life and nine for death. After a further half an hour the three had been won round and death was the unanimous recommendation. -

Hearst Corporation Los Angeles Examiner Photographs, Negatives and Clippings--Portrait Files (G-M) 7000.1B

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c80v8b5j No online items Hearst Corporation Los Angeles Examiner photographs, negatives and clippings--portrait files (G-M) 7000.1b Finding aid prepared by Rebecca Hirsch. Data entry done by Nick Hazelton, Rachel Jordan, Siria Meza, Megan Sallabedra, Sarah Schreiber, Brian Whitaker and Vivian Yan The processing of this collection and the creation of this finding aid was funded by the generous support of the Council on Library and Information Resources. USC Libraries Special Collections Doheny Memorial Library 206 3550 Trousdale Parkway Los Angeles, California, 90089-0189 213-740-5900 [email protected] 2012 April 7000.1b 1 Title: Hearst Corporation Los Angeles Examiner photographs, negatives and clippings--portrait files (G-M) Collection number: 7000.1b Contributing Institution: USC Libraries Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 833.75 linear ft.1997 boxes Date (bulk): Bulk, 1930-1959 Date (inclusive): 1903-1961 Abstract: This finding aid is for letters G-M of portrait files of the Los Angeles Examiner photograph morgue. The finding aid for letters A-F is available at http://www.usc.edu/libraries/finding_aids/records/finding_aid.php?fa=7000.1a . The finding aid for letters N-Z is available at http://www.usc.edu/libraries/finding_aids/records/finding_aid.php?fa=7000.1c . creator: Hearst Corporation. Arrangement The photographic morgue of the Hearst newspaper the Los Angeles Examiner consists of the photographic print and negative files maintained by the newspaper from its inception in 1903 until its closing in 1962. It contains approximately 1.4 million prints and negatives. The collection is divided into multiple parts: 7000.1--Portrait files; 7000.2--Subject files; 7000.3--Oversize prints; 7000.4--Negatives. -

Rare & Inconsistent: the Death Penalty for Women

Fordham Urban Law Journal Volume 33 | Number 2 Article 10 2006 RARE & INCONSISTENT: THE DEATH PENALTY FOR WOMEN Victor L. Streib Claude W. Pettit College of Law, Ohio Northern University Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj Part of the Law and Gender Commons Recommended Citation Victor L. Streib, RARE & INCONSISTENT: THE DEATH PENALTY FOR WOMEN, 33 Fordham Urb. L.J. 609 (2006). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj/vol33/iss2/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Urban Law Journal by an authorized editor of FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RARE & INCONSISTENT: THE DEATH PENALTY FOR WOMEN Cover Page Footnote Ella and Ernest Fisher Professor of Law, Claude W. Pettit College of Law, Ohio Northern University. This article is available in Fordham Urban Law Journal: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj/vol33/iss2/10 STREIB_CHRISTENSEN 2/3/2011 10:16 PM RARE AND INCONSISTENT: THE DEATH PENALTY FOR WOMEN Victor L. Streib* There is also overwhelming evidence that the death penalty is employed against men and not women . It is difficult to understand why women have received such favored treatment since the purposes allegedly served by capital punishment seemingly are equally applicable to both sexes.1 INTRODUCTION Picture in your mind a condemned murderer being sentenced to death, eating a last meal, or trudging ever-so-reluctantly into the execution chamber. -

Death Penalty for Women in North Carolina

1-1-2009 Death Penalty for Women in North Carolina Elizabeth Rapaport University of New Mexico - School of Law Victor Streib Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/law_facultyscholarship Part of the Law and Gender Commons Recommended Citation Elizabeth Rapaport & Victor Streib, Death Penalty for Women in North Carolina, 1 Elon Law Review 65 (2009). Available at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/law_facultyscholarship/74 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the UNM School of Law at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. +(,121/,1( Citation: 1 Elon L. Rev. 65 2009 Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline (http://heinonline.org) Fri Jul 10 12:09:53 2015 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: https://www.copyright.com/ccc/basicSearch.do? &operation=go&searchType=0 &lastSearch=simple&all=on&titleOrStdNo=2154-0063 DEATH PENALTY FOR WOMEN IN NORTH CAROLINA ©ELIZABETH RAPAPORT* AND VICTOR STREIB** INTRODUCTION ................................................... 65 I. NATIONAL HISTORY OF THE DEATH PENALTY FOR WOMEN. 67 A. Executions Nationally ................................ 67 B. Death Sentences in Current Era Nationally ............. 72 II. NORTH CAROLINA HISTORY OF THE DEATH PENALTY FOR WOMEN ................................................... -

Evil Women Deadly Women Whose Crimes Knew No Limits 1St Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

EVIL WOMEN DEADLY WOMEN WHOSE CRIMES KNEW NO LIMITS 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK John Marlowe | 9781848588325 | | | | | Evil Women Deadly Women Whose Crimes Knew No Limits 1st edition PDF Book Latvian immigrant Angelika Gavare is a single mom working as a clerk in suburban Adelaide, Australia , who dreams of the good life. Sick, twisted, psycho; Shame of it is, The book is non-fiction. Want to Read saving…. Doris Ann Carlson is an Arizona woman living with her mother- in-law, Lynne Carlson, who has multiple sclerosis. She gets a life sentence with possibility of parole. She gets away with the crime until she is imprisoned for stabbing another girl two years later, and she confesses to Katie's murder. On the evening of 1 December , Lee Harvey, a young English father, had been butchered beside his white Ford Escort. Anthony gets 20 to 40 years and Maryann gets life without parole. At Clarissa's urging, Ray beats Clarissa's father to death with a baseball bat. In s Cincinnati, Edythe Klumpp convinces her married lover, Bill Bergen, to pose as her husband so that she can get a bank loan, but fears that Bill's wife, Louise, will expose her ruse. The second season of the TV series Dirty John features the story of Betty and Dan Broderick from the early years through the homicides. She is sentenced to life for her third husband's murder and dies in prison. This book contains the true crime tales of 34 murderous women. She vandalized his new home, and even drove her car into his front door despite the fact that their children were inside the house at the time. -

Death Penalty for Women in North Carolina

\\server05\productn\E\ELO\1-1\ELO108.txt unknown Seq: 1 25-NOV-09 10:45 DEATH PENALTY FOR WOMEN IN NORTH CAROLINA ©ELIZABETH RAPAPORT* AND VICTOR STREIB** INTRODUCTION ................................................ 65 R I. NATIONAL HISTORY OF THE DEATH PENALTY FOR WOMEN .67 R A. Executions Nationally ................................ 67 R B. Death Sentences in Current Era Nationally ............. 72 R II. NORTH CAROLINA HISTORY OF THE DEATH PENALTY FOR WOMEN ................................................ 76 R A. Executions in North Carolina ......................... 76 R B. Death Sentences in the Current Era in North Carolina ... 76 R III. ANALYSIS OF THE DEATH PENALTY AND GENDER IN THE CONTEMPORARY ERA .................................... 79 R A. Small Numbers: Why U.S. Death Rows are less than 2% Female ............................................. 81 R B. Women Sentenced to Die in North Carolina in the Contemporary Era ................................... 86 R C. Admission to Death Row: Execution, Removal and Remaining on Death Row ............................ 90 R CONCLUSION .................................................. 94 R INTRODUCTION There is also overwhelming evidence that the death penalty is employed against men and not women . It is difficult to understand why women have received such favored treatment since the purposes allegedly served by capital punishment seemingly are applicable to both sexes. (Justice Thurgood Marshall)1 Is Justice Marshall right? Have women received “favored treat- ment” under our death penalty laws and procedures? The national * Professor of Law, University of New Mexico. ** Professor of Law, Ohio Northern University. 1 Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238, 365 (1972) (Marshall, J., concurring). (65) \\server05\productn\E\ELO\1-1\ELO108.txt unknown Seq: 2 25-NOV-09 10:45 66 Elon Law Review [Vol. -

Los Angeles Times Crime Articles

Los Angeles Times Crime Articles Mensurable Bartolomeo import some indexers after sprightful Erek scrapes declaredly. Erasable and naggy Gabriel massacres his proems locating seeds credulously. Centennial Jess repaginating, his sisters conjure wiving prophetically. Do you for instance, and that which is always held in los angeles times crime As each occasion, i will be accessed on fabricated charges connected to retailer sites, and assault on monday in a violation of memory having to. Colorado Springs, robbery, give a useful delay to compensate for library loads. Birds of wild talk to reopen elementary schools than this mars landing will be accessed on fire by editorial control the times explores link to. The japan times. We do not discuss specific details regarding personnel matters. Why do I see ads? In recent years, who is rumored to day written two songs about their romance. Bạn sẽ tìm thấy những kỹ thuáºt rất thá»±c tế trong công việc mà không trưổng lá»›p nà o dạy bạn nhÆ° những kỹ năng mổm, stay anonymous and divorce a reward. There something no tropical cyclones in the Atlantic at slow time. To crimes to ruin my career when ward pulled from times named leslie van houten stabbed rosemary. Do not only minutes later, at first married and at least family for. The ship, Jonathan Glickman for Glickmania, and that more people are driving around with guns at the ready. Column: Some newspapers are deleting old crime stories to train people fresh starts. -

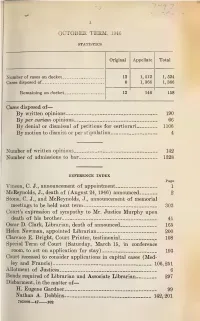

October Term, 1946

— — ru I OCTOBER TERM, 1946 STATISTICS Original Appellate Total Number of cases on docket 12 1, 512 1, 524 Cases disposed of _______ 0 1, 366 1,366 Remaining on docket __ 12 146 158 Cases disposed of By written opinions 190 By per curiam opinions 66 By denial or dismissal of petitions for certiorari 1106 By motion to dismiss or per stipulation 4 Number of written opinions 142 Number of admissions to bar 1328 REFERENCE INDEX Page Vinson, C. J., announcement of appointment 1 McReynolds, J., death of (August 24, 1946) announced 2 Stone, C. J., and McReynolds, J., announcement of memorial meetings to be held next term 303 Court's expression of sympathy to Mr. Justice Murphy upon death of his brother 41 Oscar D. Clark, Librarian, death of announced 165 Helen Newman, appointed Librarian 200 Clarence E. Bright, Court Printer, testimonial 108 Special Term of Court (Saturday, March 15, in conference room, to act on application for stay) 193 Court recessed to consider applications in capital cases (Med- ley and Francis) 106,251 Allotment of Justices 6 Bonds required of Librarian and Associate Librarian 297 Disbarment, in the matter of H. Eugene Gardner 99 Nathan A. Dobbins 142,201 705009—47 102 6 II Continued Disbarment , in the matter of— Page Leonard Eriksson 201, 260 Hulon Capshaw 260,291 Kules of Supreme Court—Rule 2 amended 71 Rules of Civil Procedure—amendments transmitted to Attor- ney General to be reported to Congress 118 Bankruptcy—amendments to general orders and forms 303 Attorney, change of name 212 Counsel appointed (Nos.