Stanwix, Religious History (Interim Draft) Jane Platt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Norman Rule Cumbria 1 0

NORMAN RULE I N C U M B R I A 1 0 9 2 – 1 1 3 6 B y RICHARD SHARPE A lecture delivered to Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society on 9th April 2005 at Carlisle CUMBERLAND AND WESTMORLAND ANTIQUARIAN AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY N O R M A N R U L E I N C U M B R I A 1 0 9 2 – 1 1 3 6 NORMAN RULE I N C U M B R I A 1 0 9 2 – 1 1 3 6 B y RICHARD SHARPE Pr o f essor of Diplomat i c , U n i v e r sity of Oxfo r d President of the Surtees Society A lecture delivered to Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society on 9th April 2005 at Carlisle CUMBERLAND AND WESTMORLAND ANTIQUARIAN AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY Tract Series Vol. XXI C&W TRACT SERIES No. XXI ISBN 1 873124 43 0 Published 2006 Acknowledgements I am grateful to the Council of the Society for inviting me, as president of the Surtees Society, to address the Annual General Meeting in Carlisle on 9 April 2005. Several of those who heard the paper on that occasion have also read the full text and allowed me to benefit from their comments; my thanks to Keith Stringer, John Todd, and Angus Winchester. I am particularly indebted to Hugh Doherty for much discussion during the preparation of this paper and for several references that I should otherwise have missed. In particular he should be credited with rediscovering the writ-charter of Henry I cited in n. -

LD19 Carlisle City Local Plan 2001-2016

Carlisle District Local Plan 2001 - 2016 Written Statement September 2008 Carlisle District Local Plan 2001-2016 Written Statement September 2008 If you wish to contact the City Council about this plan write to: Local Plans and Conservation Manager Planning and Housing Services Civic Centre Carlisle CA3 8QG tel: 01228 817193 fax: 01228 817199 e-mail: [email protected] This document can also be viewed on the Council’s website: www.carlisle.gov.uk/localplans A large print or audio version is also available on request from the above address Cover photos © Carlisle City Council; CHedley (Building site), CHedley (Irish Gate Bridge), Cumbria County Council (Wind turbines) Carlisle District Local Plan 2001-16 2 September 2008 Contents Chapter 1 Introduction Purpose of the Local Plan ........................................................................................ 5 Format of the Local Plan .......................................................................................... 5 Planning Context ....................................................................................................... 6 The Preparation Process ........................................................................................... 6 Chapter 2 Spatial Strategy and Development Principles The Vision ..................................................................................................................... 9 The Spatial Context ................................................................................................... 9 A Sustainable Strategy -

The Church Militant: the American Loyalist Clergy and the Making of the British Counterrevolution, 1701-92

The Church Militant: The American Loyalist Clergy and the Making of the British Counterrevolution, 1701-92 Peter W. Walker Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2016 © 2016 Peter Walker All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Church Militant: The American Loyalist Clergy and the Making of the British Counterrevolution, 1701-92 Peter W. Walker This dissertation is a study of the loyalist Church of England clergy in the American Revolution. By reconstructing the experience and identity of this largely-misunderstood group, it sheds light on the relationship between church and empire, the role of religious pluralism and toleration in the American Revolution, the dynamics of loyalist politics, and the religious impact of the American Revolution on Britain. It is based primarily on the loyalist clergy’s own correspondence and writings, the records of the American Loyalist Claims Commission, and the archives of the SPG (the Church of England’s missionary arm). The study focuses on the New England and Mid-Atlantic colonies, where Anglicans formed a religious minority and where their clergy were overwhelmingly loyalist. It begins with the founding of the SPG in 1701 and its first forays into America. It then examines the state of religious pluralism and toleration in New England, the polarising contest over the proposed creation of an American bishop after the Seven Years’ War, and the role of the loyalist clergy in the Revolutionary War itself, focusing particularly on conflicts occasioned by the Anglican liturgy and Book of Common Prayer. -

New Additions to CASCAT from Carlisle Archives

Cumbria Archive Service CATALOGUE: new additions August 2021 Carlisle Archive Centre The list below comprises additions to CASCAT from Carlisle Archives from 1 January - 31 July 2021. Ref_No Title Description Date BRA British Records Association Nicholas Whitfield of Alston Moor, yeoman to Ranald Whitfield the son and heir of John Conveyance of messuage and Whitfield of Standerholm, Alston BRA/1/2/1 tenement at Clargill, Alston 7 Feb 1579 Moor, gent. Consideration £21 for Moor a messuage and tenement at Clargill currently in the holding of Thomas Archer Thomas Archer of Alston Moor, yeoman to Nicholas Whitfield of Clargill, Alston Moor, consideration £36 13s 4d for a 20 June BRA/1/2/2 Conveyance of a lease messuage and tenement at 1580 Clargill, rent 10s, which Thomas Archer lately had of the grant of Cuthbert Baynbrigg by a deed dated 22 May 1556 Ranold Whitfield son and heir of John Whitfield of Ranaldholme, Cumberland to William Moore of Heshewell, Northumberland, yeoman. Recites obligation Conveyance of messuage and between John Whitfield and one 16 June BRA/1/2/3 tenement at Clargill, customary William Whitfield of the City of 1587 rent 10s Durham, draper unto the said William Moore dated 13 Feb 1579 for his messuage and tenement, yearly rent 10s at Clargill late in the occupation of Nicholas Whitfield Thomas Moore of Clargill, Alston Moor, yeoman to Thomas Stevenson and John Stevenson of Corby Gates, yeoman. Recites Feb 1578 Nicholas Whitfield of Alston Conveyance of messuage and BRA/1/2/4 Moor, yeoman bargained and sold 1 Jun 1616 tenement at Clargill to Raynold Whitfield son of John Whitfield of Randelholme, gent. -

Romans in Cumbria

View across the Solway from Bowness-on-Solway. Cumbria Photo Hadrian’s Wall Country boasts a spectacular ROMANS IN CUMBRIA coastline, stunning rolling countryside, vibrant cities and towns and a wealth of Roman forts, HADRIAN’S WALL AND THE museums and visitor attractions. COASTAL DEFENCES The sites detailed in this booklet are open to the public and are a great way to explore Hadrian’s Wall and the coastal frontier in Cumbria, and to learn how the arrival of the Romans changed life in this part of the Empire forever. Many sites are accessible by public transport, cycleways and footpaths making it the perfect place for an eco-tourism break. For places to stay, downloadable walks and cycle routes, or to find food fit for an Emperor go to: www.visithadrianswall.co.uk If you have enjoyed your visit to Hadrian’s Wall Country and want further information or would like to contribute towards the upkeep of this spectacular landscape, you can make a donation or become a ‘Friend of Hadrian’s Wall’. Go to www.visithadrianswall.co.uk for more information or text WALL22 £2/£5/£10 to 70070 e.g. WALL22 £5 to make a one-off donation. Published with support from DEFRA and RDPE. Information correct at time Produced by Anna Gray (www.annagray.co.uk) of going to press (2013). Designed by Andrew Lathwell (www.lathwell.com) The European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development: Europe investing in Rural Areas visithadrianswall.co.uk Hadrian’s Wall and the Coastal Defences Hadrian’s Wall is the most important Emperor in AD 117. -

127179758.23.Pdf

—>4/ PUBLICATIONS OF THE SCOTTISH HISTORY SOCIETY THIRD SERIES VOLUME II DIARY OF GEORGE RIDPATH 1755-1761 im DIARY OF GEORGE RIDPATH MINISTER OF STITCHEL 1755-1761 Edited with Notes and Introduction by SIR JAMES BALFOUR PAUL, C.V.O., LL.D. EDINBURGH Printed at the University Press by T. A. Constable Ltd. for the Scottish History Society 1922 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION DIARY—Vol. I. DIARY—You II. INDEX INTRODUCTION Of the two MS. volumes containing the Diary, of which the following pages are an abstract, it was the second which first came into my hands. It had found its way by some unknown means into the archives in the Offices of the Church of Scotland, Edinburgh ; it had been lent about 1899 to Colonel Milne Home of Wedderburn, who was interested in the district where Ridpath lived, but he died shortly after receiving it. The volume remained in possession of his widow, who transcribed a large portion with the ultimate view of publication, but this was never carried out, and Mrs. Milne Home kindly handed over the volume to me. It was suggested that the Scottish History Society might publish the work as throwing light on the manners and customs of the period, supplementing and where necessary correcting the Autobiography of Alexander Carlyle, the Life and Times of Thomas Somerville, and the brilliant, if prejudiced, sketch of the ecclesiastical and religious life in Scotland in the eighteenth century by Henry Gray Graham in his well-known work. When this proposal was considered it was found that the Treasurer of the Society, Mr. -

These Properties Are Listed Buildings

These properties are Listed buildings; the full details (and in most cases, a photograph) are given in the English Heritage Images of England website and may be seen by clicking on the link shown. A number of items have been excluded such as milestones, walls, gate piers, telephone kiosks. Alternative website; property added since Images of England project so not recorded there and no image available # No image available - for a number of possible reasons CENTRAL CARLISLE THE CASTLE 1. Bridge over Outer Moat 2. Captains Tower and Inner Bailey Walls 3. De Irebys Tower and Outer Bailey Wall 4. Inner Bailey Keep 5. Inner Bailey Militia Store 6. Inner Bailey Magazine 7. Inner Bailey Palace Range Including Part of Queen Mary's Tower 8. Outer Bailey Arnhem Block 9. Outer Bailey Arroyo Block, Gym and Regimental Association Club 10. Outer Bailey Gallipoli Block 11. Outer Bailey Half Moon Battery, Flanking Wall 12. Outer Bailey Garrison Cells and Custodian's Office 13. Outer Bailey Officers' Mess 14. Outer Bailey Ypres Block 15. Statue of Queen Victoria, Castle Way 16. Fragment of North City Walls Adjoining South East Angle 17. West City Walls and Tile Tower Adjoining at South West ABBEY STREET 18. 1 and 3, Abbey Street 19. Tollund House, 8 Abbey Street, 20. Herbert Atkinson House, 13 Abbey Street, 21. Tullie House and Extensions, 15 Abbey Street 22. 15a, Abbey Street 23. 17 and 19, Abbey Street 24. 18, 20 and 22, Abbey Street 25. 24, Abbey Street 26. 26, Abbey Street 27. 28 and 30, Abbey Street 28. -

A Kink in the Cosmography?

A Kink in the Cosmography? One vital clue for deciphering Roman-era names is that the order of names in the Ravenna Cosmography is geographically logical. The unknown cosmographer appears to have taken names off maps and/or itineraries that were tolerably accurate, not up to modern cartographic standards, but good enough for Roman soldiers to plan their travels logically. An apparent exception to this logic occurs near Hadrian’s Wall, where RC’s sequence of names runs thus: ... Bereda – Lagubalium – Magnis – Gabaglanda – Vindolande – Lincoigla ... The general course is clear enough, looping up from the south onto the Stanegate road (which was built earlier than the actual Wall) and then going back south. Lagubalium must be Carlisle and Vindolande must be Chesterholm, so it seems obvious that Magnis was at Carvoran and Gabaglanda was at Castlesteads. The problem is that Carvoran lies east of Castlesteads, which would make RC backtrack and put a kink in its path across the ground. Most people will simply say “So what? Cosmo made a mistake. Or his map was wrong. Or the names were written awkwardly on his map.” But this oddity prompted us to look hard at the evidence for names on and around Hadrian’s Wall, as summarised in a table on the following page. How many of the name-to-place allocations accepted by R&S really stand up to critical examination? One discovery quickly followed (a better location for Axelodunum), but many questions remain. For a start, what was magna ‘great’ about the two places that share the name Magnis, Carvoran and Kenchester? Did that name signify something such as ‘headquarters’ or ‘supply base’ in a particular period? Could another site on the Stanegate between Carlisle and Castlesteads be the northern Magnis? The fort at Chapelburn (=Nether Denton, NY59576460) would reduce the size of the kink, but not eliminate it. -

I~Ist of Bishops of Carlisle. List of Priors of Carlisle

DIOCESE OF CARLISLE. tos seen in the following numerical list, with the years hi which they were respectively inducted : • · I~IST OF BISHOPS OF CARLISLE. 1 .tEthelwald, • •• .... ·1133 19 Mannaduke Lumley 1429 38 Richard Senhonse •. 1624 2 Bemard, ......... -1157 20 Nicholas Close .... 1449 39 Frands White ...... ]626 Vacant 30 years. 21. William Percy • · · · l·M2 40 Bamaby Potter • .•. 1628 3 Hugh, . ···········1216 22 John Kingscott ····1462 41 James Usher ....•• 1641 4 Waiter, .••. • ..•••• -1223 23 Richard Scroop •• • ·1463 Vacant 6 Yt!ars. .5 SylvesterdeEverdon1246 24 Edward Storey ····1468 42 Richard Steme .... J661 6 Thos. de Vetriponte 1255 25 Richard Bell •••.. ·1478 43 Edward Rainbow .. )664 7 Robt. de Chauncey 1258 26 William Sever ••• ·1496 44 Thomas Smith .... 1684 8 Ra1ph Irton •.. •. ·1280 27 Roger Leyburn .... 1503 45 William Nicholson 1702 9 John Halton · .... -1292 28 John Penny.·· ..... }508 46 Samuel Bradford , .. 1718· 10 John Ross ..... ·····1325 29 John Kyte ... ·····1520 47 John Waugh ...... 1723 H John Kirkby .... ·1332 30 Robert Aldridge .... l537 48 George Fleming. •· ·1734 12 Gilbert Welton ••• ·1352 31 Owen Oglethorp .•. ·1556 49 Richard Osbaldiston 1747 13 Thomas Appleby · ·1363 1 32 John Best.····.· .. -1560 50 Charles Lyttleton • ·1762 14 Robert Reed · • • · • ·1396 1 33 Richard Bames • • · ·1570 51 Edmund Law .....1768 15 Thomas Merks .... 13!17 i 34 John Meye ........ 1577 52 John Douglas ..... ·1787 16 Wm. Strickland ... -1400 I 35 Henry Robinson .... J598 53 E. V. Vemon ..... ·1791 17 Roger Wht;lpdale • -1419 36 Robert Snowden. • · ·1616 I 54 Samuel Goodenough 1807 18 Wm. Barrow ..... ·1423 37 Richard Mill>urne .. 1621 55 Hon. H. Percy ••• ·1827 • • LIST OF PRIORS OF CARLISLE . -

English Duplicates of Lost Virginia Records

T iPlCTP \jrIRG by Lot L I B RAHY OF THL UN IVER.SITY Of ILLINOIS 975.5 D4-5"e ILL. HJST. survey Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign http://archive.org/details/englishduplicateOOdesc English Duplicates of Lost Virginia Records compiled by Louis des Cognets, Jr. © 1958, Louis des Cognets, Jr. P.O. Box 163 Princeton, New Jersey This book is dedicated to my grandmother ANNA RUSSELL des COGNETS in memory of the many years she spent writing two genealogies about her Virginia ancestors \ i FOREWORD This book was compiled from material found in the Public Record Office during the summer of 1957. Original reports sent to the Colonial Office from Virginia were first microfilmed, and then transcribed for publication. Some of the penmanship of the early part of the 18th Century was like copper plate, but some was very hard to decipher, and where the same name was often spelled in two different ways on the same page, the task was all the more difficult. May the various lists of pioneer Virginians contained herein aid both genealogists, students of colonial history, and those who make a study of the evolution of names. In this event a part of my debt to other abstracters and compilers will have been paid. Thanks are due the Staff at the Public Record Office for many heavy volumes carried to my desk, and for friendly assistance. Mrs. William Dabney Duke furnished valuable advice based upon her considerable experience in Virginia research. Mrs .Olive Sheridan being acquainted with old English names was especially suited to the secretarial duties she faithfully performed. -

Political Society in Cumberland and Westmorland 1471-1537

Political Society in Cumberland and Westmorland 1471-1537 By Edward Purkiss, BA (Hons). Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. School of History and Classics University of Tasmania. 2008. This Thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis and to the best of my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis, nor does the thesis contain any material that infringes copyright. 30 May, 2008. I place no restriction on the loan or reading of this thesis and no restriction, subject to the law of copyright, on its reproduction in any form. 11 Abstract The late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries have often been seen as a turning point in the development of the English state. At the beginning of the period the authority of the Crown was offset by powerful aristocratic interests in many regional areas. By the mid sixteenth century feudal relationships were giving way to a centrally controlled administration and government was reaching into regional political communities through direct connections between the Crown and local gentlemen. This thesis will trace these developments in Cumberland and Westmorland. It will argue that archaic aspects of government and society lingered longer here than in regions closer London. Feudal relationships were significant influences on regional political society well beyond the mid sixteenth century. This was a consequence of the area's distance from the centre of government and its proximity to a hostile enemy. -

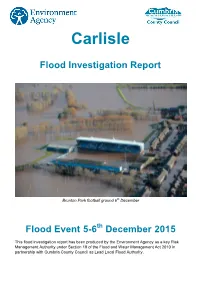

Carlisle Flood Investigation Report Final Draft

Carlisle Flood Investigation Report Brunton Park football ground 6th December Flood Event 5-6th December 2015 This flood investigation report has been produced by the Environment Agency as a key Risk Management Authority under Section 19 of the Flood and Water Management Act 2010 in partnership with Cumbria County Council as Lead Local Flood Authority. Environment Agency Version Prepared by Reviewed by Approved by Date Working Draft for 17th March 2016 Ian McCall Michael Lilley discussion with EA Second Draft following EA Ian McCall Adam Parkes 14th April 2016 Feedback Draft for CCC review Ian McCall N/A 22nd April 2016 Final Draft Ian McCall N/A 26th April 2016 First Version Ian McCall Michael Lilley 3rd May 2016 2 Creating a better place Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Flooding History ..................................................................................................................................................... 6 Event background................................................................................................................................................ 7 Flooding Incident ................................................................................................................................................... 7 Current Flood Defences ......................................................................................................................................