Conan Doyle Defence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conan Volume 16: the Song of Belit Free Download

CONAN VOLUME 16: THE SONG OF BELIT FREE DOWNLOAD Dr Brian Wood,Various | 176 pages | 19 Feb 2015 | DARK HORSE COMICS | 9781616555245 | English | Milwaukee, United States Conan (comics) Chris rated it liked it Jun 10, Creepy, the quintessential horror comics anthology from Warren Publishing, always delivered a heaping helping Conan Volume 16: The Song of Belit Mechanized weapons of hominid destruction, murderous swamp beasts, ravenous alien hybrids, and other bizarre monsters Stories, books Books Conan books. Follow us. The Conan Volume 16: The Song of Belit Age Conan chronologies. Peak human physical condition, Melee weapons master, Knowledge and experience of fighting the supernatural. This trade has one of the most heeart breaking sequences I've ever read and i feel forever changed by it. From the page future war epic DMZ, the ecological disaster series The Massive, the American crime drama Briggs Land, and the groundbreaking lo-fi dystopia Channel Zero he has a year track record of marrying thoughtful world-building and political commentary with compelling and diverse characters. Parallel related story in Conan the Barbarian 66 and continues in Conan the Barbarian King Conan: Wolves Beyond the Border. Collects Conan: The Phantoms of the Black Coast 1—5 special comics sent to digital comics subscribers and not sold in the market. King Conan: The Scarlet Citadel. Absolutely makes no sense. Authors Creator Robert E. Brian Wood's history of published work includes over fifty volumes of genre-spanning original material. Jun 05, Ben rated it it was ok Shelves: graphic-novels. Home 1 Books 2. Conan Unchained! But that will be for a future volume to reveal, unless it's a blind alley conjured up by my fevered imagination. -

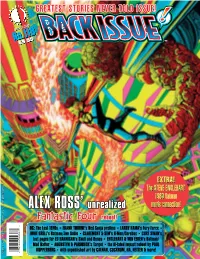

ALEX ROSS' Unrealized

Fantastic Four TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc. All Rights Reserved. No.118 February 2020 $9.95 1 82658 00387 6 ALEX ROSS’ DC: TheLost1970s•FRANK THORNE’sRedSonjaprelims•LARRYHAMA’sFury Force• MIKE GRELL’sBatman/Jon Sable•CLAREMONT&SIM’sX-Men/CerebusCURT SWAN’s Mad Hatter• AUGUSTYN&PAROBECK’s Target•theill-fatedImpact rebootbyPAUL lost pagesfor EDHANNIGAN’sSkulland Bones•ENGLEHART&VON EEDEN’sBatman/ GREATEST STORIESNEVERTOLDISSUE! KUPPERBERG •with unpublished artbyCALNAN, COCKRUM, HA,NETZER &more! Fantastic Four Four Fantastic unrealized reboot! ™ Volume 1, Number 118 February 2020 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTIST Alex Ross COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER Rob Smentek SPECIAL THANKS Brian Augustyn Alex Ross Mike W. Barr Jim Shooter Dewey Cassell Dave Sim Ed Catto Jim Simon GREATEST STORIES NEVER TOLD: Alex Ross and the Fantastic Four That Wasn’t . 2 Chris Claremont Anthony Snyder An exclusive interview with the comics visionary about his pop art Kirby homage Comic Book Artist Bryan Stroud Steve Englehart Roy Thomas ART GALLERY: Marvel Goes Day-Glo. 12 Tim Finn Frank Thorne Inspired by our cover feature, a collection of posters from the House of Psychedelic Ideas Paul Fricke J. C. Vaughn Mike Gold Trevor Von Eeden GREATEST STORIES NEVER TOLD: The “Lost” DC Stories of the 1970s . 15 Grand Comics John Wells From All-Out War to Zany, DC’s line was in a state of flux throughout the decade Database Mike Grell ROUGH STUFF: Unseen Sonja . 31 Larry Hama The Red Sonja prelims of Frank Thorne Ed Hannigan Jack C. Harris GREATEST STORIES NEVER TOLD: Cancelled Crossover Cavalcade . -

Conan Case Study.Qxp

A PLACE FOR CONAN Problem: How do you keep momentum going to get a television star back on television? Solution: Combine the flexible nature of digital billboards with social networking sites to maintain an audience. BACKGROUND: On January 21st, NBC announced that Jay Leno would replace Conan O’Brien as host of The Tonight Show. Conan O’Brien was legally prohibited from appearing on television. OBJECTIVE: A little over a month later, Conan took to the social networking site Twitter and posted his first tweet on February 24th, showing the world he can still make us laugh, with or without tele- vision. Taking notice of Conan’s dillema, an outdoor company wanted to highlight Conan’s tweets until he could find another home on tele- vision. STRATEGY: A creative image and a micro-site, www.aplace- forconan.com, were built to feature Conan’s tweets live on digital billboards. The outdoor company sent an email to all of their markets with digital inven- tory asking that they run the campaign on any available spots between paid contracts on the boards. PLAN DETAILS: Within 24 hours, the campaign went live on 224 digital panels in 66 markets. OAAA, 2010 RESULTS: Within one hour of posting on Facebook, 1800+ users claimed they “liked” it and 200+ com- mented. Almost every comment was positive. If a negative comment was made, it was usually in reference to the fact that the user did not have a digital billboard in their market that they could view Conan’s Tweets on. Within five days, aplaceforconan.com received 55,197 unique hits and 78,714 total hits. -

A Literary Biography of Conan the Barbarian (Volume 1) Pdf, Epub, Ebook

BARBARIAN LIFE : A LITERARY BIOGRAPHY OF CONAN THE BARBARIAN (VOLUME 1) PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Roy Thomas | 322 pages | 07 Dec 2018 | Pulp Hero Press | 9781683901730 | English | none Barbarian Life : A Literary Biography of Conan the Barbarian (Volume 1) PDF Book See all 3 brand new listings. Almost gone. Doesn't post to Germany See details. Be the first to write a review. Scott added it Jul 15, For ten years, from October when Roy and artist Barry Smith assembled the first issue of Marvel's Conan the Barbarian , to October when Roy and artist John Buscema completed their last issue together on the series, Thomas wrote of Conan's gigantic melancholies and gigantic mirth—as well as the wars, the wenches, and the wizardry that bedeviled the Cimmerian from one issue to the next. Listed in category:. Brand new: Lowest price The lowest- priced brand-new, unused, unopened, undamaged item in its original packaging where packaging is applicable. Skip to main content. Readers also enjoyed. There are no discussion topics on this book yet. Read more Some of his hardest victories have come from fighting single opponents, but ones of inhuman strength: one such as Thak , the ape man from " Rogues in the House ", or the strangler Baal-Pteor in " The Man-Eaters of Zamboula " "Shadows in Zamboula". Scott Rowland rated it it was amazing May 31, Conan the Barbarian No. The specter of L. Condition Details. This sequel was a more typical fantasy-genre film and was even less faithful to Howard's Conan stories. His garb is very often a loincloth or breeches and sandals, and his weapon a sword of some description, depending on his fortunes and location. -

Stone Halls & Serpent

Stone Halls & Serpent Men by Mark Damon Hughes http://markrollsdice.wordpress.com Version 2018-09-22 Table of Contents How to Play the Game Level 3 Meta Rules Level 5 Setting Level 7 Races Level 9 Gods White Magic Spells Cosmology Level 1 Calendar Level 3 Hyperborea Level 5 Western Hyperborea Level 7 Eastern Hyperborea Level 9 Storm Islands Curse Malovia Lesser Curses Gwyrdland Greater Curses Kush Cursed Crafting Characters Psionics Stats Psionic Attacks Alternative Stat Generation Methods Psionic Defenses Stat Loss Psionic Disciplines Stat Rolls Psionic Combat Race Radiation & Mutation Social Status (Optional) Advantage Mutations Professions Defect Mutations Conversions Monsters Basic Professions Bestiary Advanced Professions A-D Prestige Professions E-H Secondary Stats I-L Hit Points (HP) M-P Magic Points (MP) Q-T Alignment U-Z Languages Treasure Experience & Level Distribution of Treasure Equipment Treasure Value Material & Repair (Optional) Random Treasure Lifestyle & Maintenance (Optional) Magic Weapons Price Lists Potions Combat Miscellaneus Magic Items To Hit Table Artifacts Sequence of Play Referee's Tools Mapless Combat (Optional, Recommended for Old-School) Escaping the Underworld Weapon vs Armor Type (Optional) Fortune Cards Combat Fatigue (Optional) Action Cards Adventures Place Names Adventuring Hazards Wilderness Features Cave-In Lair Drain Chamber Hazard Doors Light Trap Search Trash Area Level Community Travel Community Events Weather Castle Deprivation Shrine Swimming & Underwater Adventuring Ruin Encounters Campsite Encounter Reaction Tomb Henchmen & Hirelings Dungeon Gambling Unusual Feature Law & Order Inspirational Movies & Literature Magic Stone Halls & Serpent Men: Character Sheet Black Magic Spells OPEN GAME LICENSE Version 1.0a Level 1 How to Play the Game Meta Rules How to play: Read A Quick Primer for Old-School Gaming by Matthew Finch These rules are balanced to be equivalent to any "Compatible" fantasy game, specifically the OGL 3.5 edition. -

Conan the Avenger # 8 - Cover A, 1St Printing

Rust Belt Comics - 8087 Cliffview Dr Phone: 330-207-0110 - Email: [email protected] Poland, OH 44514 Conan the Avenger # 8 - Cover A, 1st Printing Brand: Dark Horse Product Code: D2-545-8-A-1 Availability: 1 Price: $2.00 Ex Tax: $2.00 Short Description VF/NM condition. Stock photo. Description Rustbeltcomics.com is selling Conan the Avenger # 8 - Cover A, 1st Printing by Dark Horse in VF/NM for $2. Stock photo, inquire for actual comic book photos. Buy unlimited comics for just $3.99 shipping. Shipping cost added at checkout. We have a 30 day refund policy if not satisfied with your purchase. $3.99 Shipping- Unlimited Comics Shipping is $3.99 total regardless of the number of comics you order. We ship all comics in boxes via Media Mail so your comics arrive at your house in the same condition that we shipped them in. Comics shipped via Media Mail may take up to eight days to arrive. If you want your comics via a faster shipping method or live outside of the United States please contact us before you order for a shipping quote. Return Policy We want you to be happy with your purchases from us. If you are not satisfied with your purchase for any reason please contact us so we can try to make it right. We offer returns within 30 days of purchase. Our return policy does not cover lost or damaged packages that did not include insurance. About Us Hi, we are Matt and Mike of Rust Belt Comics in Youngstown, Ohio. -

Ebook Download Conan Chronicles Epic Collection

CONAN CHRONICLES EPIC COLLECTION: THE BATTLE OF SHAMLA PASS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Tim Truman | 472 pages | 14 Jan 2020 | Marvel Comics | 9781302921910 | English | New York, United States Conan Chronicles Epic Collection: The Battle Of Shamla Pass PDF Book Cail marked it as to-read Nov 02, This is the company that is ambushed and destroyed in the infamous Battle of Shamla Pass. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Want to Read saving…. In this article: Conan the Barbarian , Marvel. Combining Orders If you submit more than one order, we will automatically combine your orders and refund any excess shipping eBay charged you as long as we have not already processed your previous order. But what grotesque horrors await him in the Hall of the Dead? Sign up. This will likely increase the time it takes for your changes to go live. Then, a lingering curse follows Conan on his journey back to his homeland - and great darkness lies ahead in a doomed city! Consider supporting us and independent comics journalism by becoming a patron today! We are currently experiencing delays in processing and delivering online orders. View Product. Ernest Elias marked it as to-read Jun 03, Presenting all-action adaptations of classic Robert E. Contact Us for more info. Dec 28, Alex rated it it was amazing. Then he becomes the General of the Army for Princess Yasmela and eventually becomes the Lord of Amalr The fourth volume of the Epic Collection continues in the fine tradition of excellent story telling and great artwork of the previous volumes. -

The Celtic Roots of Meriadoc Brandybuck by Lynn Forest-Hill

The Tolkien Society – Essays www.tolkiensociety.org The Celtic Roots of Meriadoc Brandybuck By Lynn Forest-Hill Readers of The Lord of the Rings do not seem perplexed by the name Peregrin Took (Pippin), perhaps because any dictionary will tell them that Peregrin means 'pilgrim' and 'Pippin' is familiar as a name for a small rosy apple. But many readers express an interest in the unusual naming of Merry Brandybuck. This is a brief outline of some of the Celtic background to his unusual name 'Meriadoc'. The texts used for this outline are: The History of the Kings of Britain Geoffrey of Monmouth trans. Lewis Thorpe (London: Penguin, 1966). The Mabinogion trans. Gwyn Jones and Thomas Jones (London: Dent, 1974). The Lais of Marie de France trans. Glyn S. Burgess (London: Penguin, 1986). The Arthur of the Welsh Rachel Bromwich et al, (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1991). Encyclopaedia Britannica (1965) In most cases I have abstracted information from a good deal of elaboration. I have quoted directly where this is necessary, and indicated this with quotation marks. The Encyclopaedia Britannica provides some information regarding real lords bearing the name Conan: Celts from Britain fled from the invading Saxons in the 5th and 6th centuries. Brittany in France was known as Armorica before this influx of Celts from Britain. Celtic Brittany divided into several petty lordships. The Merovingian and Capetian Frankish dynasties tried to impose over-lordship but were resisted. In the 10th century Conan of Rennes became overlord. His line ended in 12th century after long struggle against Breton feudal lords. -

Conan the Barbarian ______

In Defense of Conan the Barbarian ___________________________________ The Anarchism, Primitivism, & Feminism of Robert Ervin Howard Robert E. Howard has been the subject of numerous media, including several biographies and a movie. He is known and well-remembered as the creator of Conan the Cimmerian Kull of Atlantis, and the Puritan demon-hunter, Solomon Cane. His most famous creation by far, Conan has secured an immoveable foothold in the popular consciousness, and has created an enduring legacy for an author whose career lasted just over a decade. Unfortunately, due mostly to the Schwarzenegger films of the 80s, this legacy- the image of Conan in the public mind- is an undue blemish on a complex, intelligent character, and on Howard himself. In Defense of Conan the Barbarian seeks to invalidate these stereotypes, and to illuminate the social, political, economic, and ethical content of the Howard's original Conan yarns. ANTI-COPYRIGHT 2011 YGGDRASIL DISTRO [email protected] a new addition to Hyborian Scholarship by: yggdrasildistro.wordpress.com Please reprint, republish, & redistribute. ROWAN WALKINGWOLF "Barbarism is the natural state of mankind. Civilization is unnatural. It is a whim of circumstance. And barbarism must always ultimately triumph." "Is it not better to die honorably than to live in infamy? Is death worse than oppression, slavery, and ultimate destruction?" skeptical questions posed by José Villarrubia's in the beginning of Conan the Barbarian. Conan the Cimmerian. Conan, King of this essay: Aquilonia. Call him what you will, most everyone in contemporary Western society is familiar with this pulp icon to "I have often wondered..."What is the appeal of Conan the some extent. -

The Hyborian Review Volume 4, Number 2

The Hyborian Review Volume 4, Number 2. July 31, 1998 In partial fulfillment of REHupa requirements Produced by Garret Romaine Notes from a frenzied situation... Purpose Statement: Things are accelerating nicely right now. I'm This publication is dedicated to the most comfortable with my Internet column every two months, enduringly popular character ever and I placed a "Career Enhancement" piece in the local produced by Robert E. Howard. computer magazine. And I finally broke through to a national PC magazine -- PC Today has assigned me 4,000 words at 30 cents per word for mid-August. While other characters and ideas will pop up from time to time, the main thrust I couldn't help thinking of Robert E. Howard when I got of this publication is to document the the contract for 30 cents a word. Technical journalism is intricacies of a barbarian's barbarian, a grind-it-out, cut 'n paste world where the words add up quickly, almost mindlessly. To craft the mystical worlds Conan of Cimmeria. and compelling characters Howard worked out for ½ a penny a word...and then not get paid to boot... Comics, movies, magazines, Internet, and other resources will be discussed. I've missed PulpCon yet again...Ohio in July is just too far away. I was there in spirit, however. And of course -- when time permits -- mailing comments... - Garret Romaine Hero with a single face by Garret Romaine In our Internet connected, film-at-11world, we are force- The first thought that popped into my head when I fed a never-ending gallery of faces, and left to our own started with this essay was the classic line from Tina wits to sort out which ones merit another glance and Turner, of all people: "We don't need another hero..." which ones are just milking their 15 minutes. -

Back Numbers 11 Part 1

In This Issue: Columns: Revealed At Last........................................................................... 2-3 Pulp Sources.....................................................................................3 Mailing Comments....................................................................29-31 Recently Read/Recently Acquired............................................32-39 The Men Who Made The Argosy ROCURED Samuel Cahan ................................................................................17 Charles M. Warren..........................................................................17 Hugh Pentecost..............................................................................17 P Robert Carse..................................................................................17 Gordon MacCreagh........................................................................17 Richard Wormser ...........................................................................17 Donald Barr Chidsey......................................................................17 95404 CA, Santa Rosa, Chandler Whipple ..........................................................................17 Louis C. Goldsmith.........................................................................18 1130 Fourth Street, #116 1130 Fourth Street, ASILY Allan R. Bosworth..........................................................................18 M. R. Montgomery........................................................................18 John Myers Myers ..........................................................................18 -

Released 26Th August

Released 26th August DARK HORSE COMICS JUN150056 CONAN THE AVENGER #17 JUN150013 FIGHT CLUB 2 #4 MAIN MACK CVR JUN150054 HALO ESCALATION #21 JUN150079 HELLBOY IN HELL #7 APR150076 KUROSAGI CORPSE DELIVERY SERVICE OMNIBUS ED TP BOOK 01 JUN150023 MULAN REVELATIONS #3 JUN150015 NEW MGMT #1 MAIN KINDT CVR JUN150021 PASTAWAYS #6 APR150057 SUNDOWNERS TP VOL 02 JUN150022 TOMORROWS #2 APR150043 USAGI YOJIMBO SAGA LTD ED HC VOL 04 APR150042 USAGI YOJIMBO SAGA TP VOL 04 JUN150045 ZODIAC STARFORCE #1 DC COMICS JUN150176 AQUAMAN #43 JUN150241 BATGIRL #43 JUN150249 BATMAN 66 #26 JUN150247 BATMAN ARKHAM KNIGHT GENESIS #1 JUN150182 CYBORG #2 JUN150204 DEATHSTROKE #9 MAY150262 EFFIGY TP VOL 01 IDLE WORSHIP (MR) JUN150188 FLASH #43 MAY150246 GI ZOMBIE A STAR SPANGLED WAR STORY TP JUN150253 GOTHAM BY MIDNIGHT #8 JUN150255 GRAYSON #11 JUN150257 HARLEY QUINN #19 JUN150273 HE MAN THE ETERNITY WAR #9 JUN150203 JLA GODS AND MONSTERS #3 JUN150196 JUSTICE LEAGUE 3001 #3 MAY150242 JUSTICE LEAGUE DARK TP VOL 06 LOST IN FOREVER JUN150169 JUSTICE LEAGUE OF AMERICA #3 JUN150215 PREZ #3 APR150324 SCALPED HC BOOK 02 DELUXE EDITION (MR) JUN150270 SINESTRO #14 JUN150234 SUPERMAN #43 DEC140428 SUPERMAN BATMAN MICHAEL TURNER GALLERY ED HC JUN150221 TEEN TITANS #11 JUN150264 WE ARE ROBIN #3 IDW PUBLISHING JUN150439 ANGRY BIRDS COMICS HC VOL 03 SKY HIGH JUN150446 BEN 10 CLASSICS TP VOL 05 POWERLESS MAY150348 DIRK GENTLYS HOLISTIC DETECTIVE AGENCY #3 JUN150363 DRIVE #1 JUN150431 GHOSTBUSTERS GET REAL #3 JUN150375 GODZILLA IN HELL #2 MAY150423 JOE FRANKENSTEIN HC APR152727 MACHI