The Big Chill: Third-Party Documents and the Reporter's Privilege

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open House Program

Open House Agenda Monday, October 7, 2019 | 8:45 a.m. - 5:00 p.m. | North Gate Hall Twitter: @UCBSOJ | Instagram: @BerkeleyJournalism Hashtags: #UCBSOJ #BerkeleyJournalism Open House is designed for prospective students to attend as many of the day’s sessions as they wish, creating a day that best suits their needs. The expectation is that attendees will come and go from classes and information sessions as needed. Events (See Bios and Descriptions for more info) 8:45 am – 9:00 am Coffee & Refreshments (Courtyard) 10:00 am – 10:30 am Career Planning (Room B1) 10:30 am – 11:00 am Financial Planning (Room B1) 11:30 am – Noon Welcome Address by Dean Wasserman (Library) Noon – 1:00 pm Lunch (Courtyard) We’ll have themed lunch tables which you can join in order to learn more about different reporting areas. Table Reporting Themes: Audio | Democracy & Inequality | Documentary | Health, Science & Environment | Investigative | Multimedia | Narrative Writing | Photojournalism | Shortform Video 1:00 pm - 1:30 pm Investigative Reporting Program Talk (Library) 1:30 pm - 2:15 pm Chat with IRP (IRP Offices across the street, 2481 Hearst Avenue - Drop-In) 2:15 pm - 3:00 pm Chat with the Dean (Dean’s Office - Drop-In) 3:00 pm - 4:00 pm Student Panel: The Student Perspective (Library) 4:00 pm - 5:00 pm Reception with current students, faculty & staff Classes (See Bios and Descriptions for more info) 9:00 am – Noon Reporting the News J200 Sections: Democracy & Inequality Instructor: Chris Ballard | Production Lab Health & Environment Instructor: Elena Conis -

PRACHTER: Hi, I'm Richard Prachter from the Miami Herald

Bob Garfield, author of “The Chaos Scenario” (Stielstra Publishing) Appearance at Miami Book Fair International 2009 PACHTER: Hi, I’m Richard Pachter from the Miami Herald. I’m the Business Books Columnist for Business Monday. I’m going to introduce Chris and Bob. Christopher Kenneally responsible for organizing and hosting programs at Copyright Clearance Center. He’s an award-winning journalist and author of Massachusetts 101: A History of the State, from Red Coats to Red Sox. He’s reported on education, business, travel, culture and technology for The New York Times, The Boston Globe, the LA Times, the Independent of London and other publications. His articles on blogging, search engines and the impact of technology on writers have appeared in the Boston Business Journal, Washington Business Journal and Book Tech Magazine, among other publications. He’s also host and moderator of the series Beyond the Book, which his frequently broadcast on C- SPAN’s Book TV and on Book Television in Canada. And Chris tells me that this panel is going to be part of a podcast in the future. So we can look forward to that. To Chris’s left is Bob Garfield. After I reviewed Bob Garfield’s terrific book, And Now a Few Words From Me, in 2003, I received an e-mail from him that said, among other things, I want to have your child. This was an interesting offer, but I’m married with three kids, and Bob isn’t quite my type, though I appreciated the opportunity and his enthusiasm. After all, Bob Garfield is a living legend. -

Reporters Workshop

Reporters 2015 Reporters’ Workshop Celia Ampel Daily Business Review [email protected] 305-347-6672 Covers circuit civil and appellate courts as well as judicial administration and court operations. Greg Angel WPEC-CBS 12 West Palm Beach [email protected] 561-891-9956 A general assignment reporter, with his assignments including court coverage and legal- related stories. He attended this workshop in 2012, while working for WTXL-TV in Tallahassee. Kate Bradshaw Creative Loafing [email protected] 813-739-4805 The news and politics editor for Creative Loafing, she is the primary contributor to the blog Political Animal and writes weekly features about local government and political issues in Creative Loafing's print edition. Benjamin Brasch Fort Myers News-Press [email protected] 239-910-3340 Joined the News-Press in April, and his coverage of the trial of Michael Spiegel – convicted of killing his ex-wife and her fiancé - was closely followed on the web and in social media. Kristen Clark Miami Herald [email protected] 850-222-3095 The newest member of the Herald’s Tallahassee bureau. Steve Contorno Tampa Bay Times [email protected] 813-226-3433 Covers Hillsborough County government, after coming to the Times from its sister operation Politifact. Joe Daraskevich Florida Times-Union [email protected] 904-359-4308 Night cops reporter who helps out on the digital team as well. Michael "Scott" Davidson Sarasota Herald-Tribune [email protected] 850-261-7309 Covers the city of North Port. In July, he published a year-long investigation into the city’s police K-9 unit. -

The Common Law Powers of the New York State Attorney General

THE COMMON LAW POWERS OF THE NEW YORK STATE ATTORNEY GENERAL Bennett Liebman* The role of the Attorney General in New York State has become increasingly active, shifting from mostly defensive representation of New York to also encompass affirmative litigation on behalf of the state and its citizens. As newly-active state Attorneys General across the country begin to play a larger role in national politics and policymaking, the scope of the powers of the Attorney General in New York State has never been more important. This Article traces the constitutional and historical development of the At- torney General in New York State, arguing that the office retains a signifi- cant body of common law powers, many of which are underutilized. The Article concludes with a discussion of how these powers might influence the actions of the Attorney General in New York State in the future. INTRODUCTION .............................................. 96 I. HISTORY OF THE OFFICE OF THE NEW YORK STATE ATTORNEY GENERAL ................................ 97 A. The Advent of Affirmative Lawsuits ............. 97 B. Constitutional History of the Office of Attorney General ......................................... 100 C. Statutory History of the Office of Attorney General ......................................... 106 II. COMMON LAW POWERS OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL . 117 A. Historic Common Law Powers of the Attorney General ......................................... 117 B. The Tweed Ring and the Attorney General ....... 122 C. Common Law Prosecutorial Powers of the Attorney General ................................ 126 D. Non-Criminal Common Law Powers ............. 136 * Bennett Liebman is a Government Lawyer in Residence at Albany Law School. At Albany Law School, he has served variously as the Executive Director, the Acting Director and the Interim Director of the Government Law Center. -

Rubio Leads Murphy in New FAU Poll, but 12 Percent Remain Undecided @Jeremyswallace

« Debbie Wasserman Schultz's misleading claim about Obamacare insurers | Main | Fact-checking Patrick Murphy's claim about his father's firm and Donald Trump » Rubio leads Murphy in new FAU poll, but 12 percent remain undecided @JeremySWallace U.S. Sen. Marco Rubio has a narrow lead over Congressman Patrick Murphy heading into the final stretch of the campaign, but there are still a sizeable number of undecided voters, a new poll from the Florida Atlantic University Business and Economics Polling Initiative shows. The poll of 500 likely voters showed 46 percent are backing Rubio, the Miami Republican seeking a second term. About 42 percent said they were backing Murphy, the two-term Democratic Congressman from Palm Beach County. But 12 percent said they were undecided on the contest - double the number that said they are undecided about th presidential race in the same poll. The FAU poll showed Hillary Clinton leading Donald Trump 46 percent to 43 percent, with 6 percent undecided. “The U.S. Senate race is very tight,” said Monica Escaleras, director of FAU’s Business and Economics Polling Initiative. Other findings in the poll conducted from Oct. 21 to Oct. 23 showed: -68 percent of Hispanic voters supporting Clinton, compared to 19 percent for Trump -37 percent of voters said Rubio’s support of Trump would make them less likely to vote for him, while 30 percent said it made them more likely to support him, and -67 percent support Amendment 2, the proposal to allow medical marijuana in Florida Posted by Jeremy Wallace on Wednesday, Oct. -

U.S. Media Reporting of Sea Level Rise & Climate Change

U.S. media reporting of sea level rise & climate change Coverage in national and local newspapers, 2001-2015 Akerlof, K. (2016). U.S. media coverage of sea level rise and climate change: Coverage in national and local newspapers, 2001-2015. Fairfax, VA: Center for Climate Change Communication, George Mason University. The cover image of Miami is courtesy of NOAA National Ocean Service Image Gallery. Summary In recent years, public opinion surveys have demonstrated that people in some vulnerable U.S. coastal states are less certain that sea levels are rising than that climate change is occurring.1 This finding surprised us. People learn about risks in part through physical experience. As high tide levels shift ever upwards, they leave their mark upon shorelines, property, and infrastructure. Moreover, sea level rise has long been tied to climate change discourses.2 But awareness of threats can also be attenuated or amplified as issues are communicated across society. Thus, we turned our attention to the news media to see how much reporting on sea level rise has occurred in comparison to climate change from 2001-2015 in four of the largest and most prestigious U.S. newspapers—The Washington Post, The New York Times, Los Angeles Times, and The Wall Street Journal—and four local newspapers in areas of high sea level rise risk: The Miami Herald, Norfolk/Virginia Beach’s The Virginian-Pilot, Jacksonville’s The Florida Times-Union, and The Tampa Tribune.3,4 We find that media coverage of sea level rise compared to climate change is low, even in some of the most affected cities in the U.S., and co-occurs in the same discourses. -

Allenneuharth3 ( .Pdf )

1 AL NEUHARTH BIOGRAPHY Al Neuharth was born in Eureka, South Dakota, on March 22, 1924. He grew up amid rural poverty and lost his father in a farm accident at age two. At age eleven, he took his first job as a newspaper carrier and in high school, began writing for the school paper. He eventually became editor of the school paper and worked in the composing room of the weekly Alpena [South Dakota] Journal . After graduating from Alpena High School, he enlisted in the Army. He was assigned to the 86 th Infantry Division and was shipped to Europe to join General Patton’s Third Army racing toward Germany. He earned a Bronze Star and the Combat Infantryman’s Badge. After the war, Neuharth returned to South Dakota, married his sweetheart and enrolled at the University of South Dakota. He majored in journalism, graduated in 1950 and took a position with the Associated Press in Sioux Falls, S. D. as a reporter. In 1952, he and a friend launched a statewide weekly tabloid, called So Dak Sports, devoted to high school athletics in South Dakota. After raising $50,000 to start the paper, Neuharth and his partner went bankrupt in two years due to lack of advertising and poor management. Neuharth learned from his failure and, in 1953, looking forward to a new start in a different part of the country, accepted a job as a reporter for the Miami Herald. In the next seven years, Neuharth worked his way up from reporter to assistant managing editor. While supervising the state coverage for the Miami Herald, he fell in love with the Cape Canaveral- Cocoa Beach (Florida) area. -

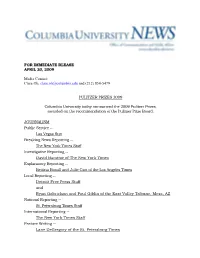

Office of Public Information

FOR IMMEDIATE RLEASE APRIL 20, 2009 Media Contact: Clare Oh, [email protected] and (212) 854-5479 PULITZER PRIZES 2009 Columbia University today announced the 2009 Pulitzer Prizes, awarded on the recommendation of the Pulitzer Prize Board. JOURNALISM Public Service -- Las Vegas Sun Breaking News Reporting -- The New York Times Staff Investigative Reporting -- David Barstow of The New York Times Explanatory Reporting -- Bettina Boxall and Julie Cart of the Los Angeles Times Local Reporting -- Detroit Free Press Staff and Ryan Gabrielson and Paul Giblin of the East Valley Tribune, Mesa, AZ National Reporting -- St. Petersburg Times Staff International Reporting -- The New York Times Staff Feature Writing -- Lane DeGregory of the St. Petersburg Times Commentary -- Eugene Robinson of The Washington Post Criticism -- Holland Cotter of The New York Times Editorial Writing -- Mark Mahoney of The Post-Star, Glens Falls, NY Editorial Cartooning -- Steve Breen of The San Diego Union-Tribune Breaking News Photography -- Patrick Farrell of The Miami Herald Feature Photography -- Damon Winter of The New York Times LETTERS AND DRAMA Fiction -- Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout (Random House) Drama -- Ruined by Lynn Nottage History -- The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family by Annette Gordon- Reed (W.W. Norton & Company) Biography -- American Lion: Andrew Jackson in the White House by Jon Meacham (Random House) Poetry -- The Shadow of Sirius by W. S. Merwin (Copper Canyon Press) General Nonfiction -- Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II by Douglas A. Blackmon (Doubleday) MUSIC Double Sextet by Steve Reich, premiered March 26, 2008 in Richmond, VA (Boosey & Hawkes). -

A Blueprint for Success

The McClatchy Company 2007 Annual Report A BLUEPRINT FOR SUCCESS THE McCLATCHY COMPANY is the third largest newspaper company in the United States, with 30 daily newspapers, approximately 50 non-dailies, and direct marketing and direct mail operations. McClatchy also operates leading local websites in each of its markets which extend its audience reach. The websites offer users information, comprehensive news, advertising, e-commerce and other services.Together with its newspapers and direct marketing products, these interactive operations make McClatchy the leading local media company in each of its premium high growth markets. McClatchy-owned newspapers include The Miami Herald, The Sacramento Bee, The Fort Worth Star-Telegram, The Kansas City Star, The Charlotte Observer, and The (Raleigh) News & Observer. McClatchy also has a portfolio of premium digital assets.The company owns and operates McClatchy Interactive, an interactive operation that provides websites with content, publishing tools and software development. McClatchy owns 14.4% of CareerBuilder, the nation’s largest online job site and owns 25.6% of Classified Ventures, a newspaper industry partnership that offers two of the nation’s premier classified websites: the auto website, cars.com, and the rental site, apartments.com. McClatchy is listed on the New York Stock Exchange under the symbol MNI. THE MCCLATCHY COMPANY 2007 ANNUAL REPORT PAGE 1 A BLUEPRINT FOR SUCCESS We are focused on four major areas: driving new revenues, with a particular emphasis on online advertising; -

Miami-Dade Transportation Board Under Siege for Being Too Large | Naked Politics

Miami-Dade transportation board under siege for being too large | Naked Politics naked politics « Gift ban anything but in Tallahassee | Main | PolitiFact looks at Hillary Clinton's claim about her grandparents » Miami-Dade transportation board under siege for being too large http://miamiherald.typepad.com/nakedpolitics/2015/04/miami-dade-transportation-board-under-siege-for-being-too-large.html[6/3/2015 1:38:37 PM] Miami-Dade transportation board under siege for being too large | Naked Politics @doug_hanks A county transportation board is the subject of a Tallahassee fight over how many people should get to run it. Miami-Dade's 23-member Metropolitan Planning Organization can be controlled by the County Commission, since the 13 elected commissioners make up a majority of MPO's membership. A state bill backed by Miami Beach Mayor Philip Levine, Miami City Commissioner Francis Suarez and others would cut membership down to 12, mainly by reducing county-commission seats to four. The mayor of Miami-Dade would get a vote for the first time, and Miami-Dade's six largest cities would retain their seats. One seat would still belong to the county's toll authority. But seats reserved for the school board, an at-large elected municipal official, and a civilian from the suburbs would each go away. The proposed changes haven't sat well with county commissioners. Chairman Jean Monestime, who also serves as chair of the MPO, wrote the sponsor of the proposal, Rep. Jeanette Nuñez of Miami, a letter this week urging her to rewrite her plan. "By dramatically reducing the number of officials serving on the MPO, you would significantly erode the http://miamiherald.typepad.com/nakedpolitics/2015/04/miami-dade-transportation-board-under-siege-for-being-too-large.html[6/3/2015 1:38:37 PM] Miami-Dade transportation board under siege for being too large | Naked Politics breadth of representation and the very legitimacy of this federally certified planning body," Monestime wrote. -

The Miami Herald Building

The Miami Herald Building 1 Herald Plaza Miami, Florida Photo from Miami Herald 1963 Advertising Brochure, courtesy of the Alvah H. Chapman, Jr. Archives Proposal for Historic Designation Report REPORT TO THE HISTORIC AND ENVIRONMENTAL PRESERVATION BOARD ON THE POTENTIAL FOR DESIGNATION FOR THE MIAMI HERALD BUILDING 1 HERALD PLAZA MIAMI, FLORIDA Prepared by: Morris Hylton III Director of Historic Preservation Program University of Florida Becky Roper Matkov CEO of Dade Heritage Trust Blair Mullins Masters of Historic Preservation Student University of Florida Submitted: July 23, 2012 2 Contents Page I: General Information 4 II: Summary of Significance 7 III: Criteria for Determination/Significance for Designation 12 IV: Physical Description of Property 40 V: Incentives to Adaptive Use 43 VI: Bibliography 43-45 3 I: General Information Historic Name: Miami Herald Building Specific Dates: 1963 Architects: Naess and Murphy Architects of Chicago, Illinois Location: 1 Herald Plaza Miami, FL 33132 Present Owner: Resorts World Miami, LLC (Formerly known as Bayfront 2011 Property, LLC) 1 Herald Plaza Miami, FL 33132 Managing Member, Genting Florida LLC 1501 Biscayne Blvd., Suite 107 Miami, FL 33132 Present Use: Miami Herald/El Nuevo Herald Newspaper Production and Offices; Brown Mackie College Educational Facilities Present Zoning: T6-36B-0, General Commercial Land Use Designation Tax Folio Number: 01-3231-045-0010 Boundary Description: Located in the City of Miami, Florida, the building is bounded on the North by NE 15th Street/Venetian Causeway, on the East by the Biscayne Bay, on the South by the MacArthur Causeway, and on the East by Herald Plaza. 4 The Miami Herald Building 1 Herald Plaza Overview of Location Site Map Zoning Map 5 Aerial Map 6 II: SUMMARY OF SIGNIFICANCE Opened in 1963, the Miami Herald Building embodies many of the ideals and characteristics that came to define Miami’s postwar era and its architecture. -

Miami Herald, Nuevo Herald and Radio Martí Teaching Note CSJ-10-0026.3

CSJ‐ 10 ‐ 0026.3 When the story is us: Miami Herald, Nuevo Herald and Radio Martí Teaching Note Case Summary The press, as the journalist Walter Lippman famously wrote, “is like the beam of a searchlight that moves restlessly about, bringing one episode and then another out of darkness.” Typically that light focuses outwards, highlighting events and issues that lie beyond the world of journalism. But media attention can also be turned inwards, so that journalists themselves become the center of the story. This case focuses on one such occasion when journalists became the news. In September 2006, the Miami Herald (TMH) ran a front page story by reporter Oscar Corral that reported 10 local journalists had accepted money from a US government‐backed broadcast that opposed Cuba’s communist leader, Fidel Castro. Three of the journalists who had been paid by Radio/TV Martí worked at El Nuevo Herald (ENH), TMH’s Spanish‐language sister publication that was also owned by the Miami Herald Publishing Company. Publisher Jesús Díaz, Jr. fired the reporters on the eve of the story’s publication, a step that drew strong reaction from journalists at both papers, as well as the Cuban‐American community that accused the Miami Herald of racism. As feelings intensified, Miami Herald columnist Carl Hiassen submitted a piece that took a humorous approach to the story. Wary of exacerbating tensions, Díaz spiked the column. With Hiassen now threatening to quit, and ENH running a counter story to the Miami Herald’s that highlighted journalists who worked for other government‐funded stations with no consequences, matters moved up the chain of command to the McClatchy Company that owned both publications.