CLIMATE CHANGE in the HEADWATERS Water and Snow Impacts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trait Ridge Road Guide

Sign No. 9 Medicine Bow Curve (11,640 feet) succeeded more than 80 years ago in bringing water from Never The sign here points northwest to the Medi Summer streams through the Grand Ditch and La Poudre Pass Rocky Mountain National Park cine Bow Mountains which extend into Wyo to irrigate the semiarid lands east of the Rockies. He failed to 9 ming, 44 miles away. The Cache la Poudre find sufficient precious metals in Lulu City diggings to establish River twists through the glacial gorge before profitable mines. Broken stone chimneys and rotting founda you, separating this point from rounded, tion logs are all that remain of this once bustling mining camp. v 7 This country is also a favorite home of the beaver. Trait Ridge brownish Specimen Mountain to the west. Its color provides a clue to the mountain's orgin, Sign No. 12 Shadow Mountain National as a volcano, and the cliffs at Iceberg Lake Recreation Area are of lava from this source. Shadow Mountain Lake and Lake Granby Road Guide Sign No. 10 Continental Divide, Milner Pass are two reservoirs of the Colorado — Big (10,758 feet) 12 Thompson Project, built and operated by the Bureau of Reclamation, U.S. Department of Surprise! You thought the Continental Divide \ 7 the Interior. From here water flows through would be the highest point on your trip. But Grand Lake and the 13.1-mile Adams Tunnel this delightful spot where an undecided rain to Estes Park. There, east of the Continental drop might flow either to the Atlantic or to \10/ Divide, it stairsteps down through penstocks the Pacific is more than a thousand feet below and turbines producing electric power and finally emptying into the Alpine Visitor Center, and 1,425 feet be- reservoirs and irrigation canals east of the Front Range. -

Page 5 of the 2020 Antelope, Deer and Elk Regulations

WYOMING GAME AND FISH COMMISSION Antelope, 2020 Deer and Elk Hunting Regulations Don't forget your conservation stamp Hunters and anglers must purchase a conservation stamp to hunt and fish in Wyoming. (See page 6) See page 18 for more information. wgfd.wyo.gov Wyoming Hunting Regulations | 1 CONTENTS Access on Lands Enrolled in the Department’s Walk-in Areas Elk or Hunter Management Areas .................................................... 4 Hunt area map ............................................................................. 46 Access Yes Program .......................................................................... 4 Hunting seasons .......................................................................... 47 Age Restrictions ................................................................................. 4 Characteristics ............................................................................. 47 Antelope Special archery seasons.............................................................. 57 Hunt area map ..............................................................................12 Disabled hunter season extension.............................................. 57 Hunting seasons ...........................................................................13 Elk Special Management Permit ................................................. 57 Characteristics ..............................................................................13 Youth elk hunters........................................................................ -

C E N Oz Oi C C Oll a Ps E of T H E E Ast Er N Ui Nt a M O U Nt Ai Ns a N D Dr Ai

Research Paper T H E M E D I S S U E: C Revolution 2: Origin and Evolution of the Colorado River Syste m II GEOSPHERE Cenozoic collapse of the eastern Uinta Mountains and drainage evolution of the Uinta Mountains region G E O S P H E R E; v. 1 4, n o. 1 Andres Aslan 1 , Marisa Boraas-Connors 2 , D o u gl a s A. S pri n k el 3 , Tho mas P. Becker 4 , Ranie Lynds 5 , K arl E. K arl str o m 6 , a n d M att H eizl er 7 1 Depart ment of Physical and Environ mental Sciences, Colorado Mesa University, 1100 North Avenue, Grand Junction, Colorado 81501, U S A doi:10.1130/ G E S01523.1 2 Depart ment of Geosciences, Colorado State University, Natural Resources Building, Roo m 322, Fort Collins, Colorado 80523, U S A 3 Utah Geological Survey, 1594 W North Te mple, Salt Lake City, Utah 84114-6100, U S A 1 5 fi g ur e s; 1 t a bl e; 4 s u p pl e m e nt al fil e s 4 Exxon Mobil Exploration Co mpany, 22777 Spring woods Village Park way, Spring, Texas 77389, U S A 5 Wyo ming State Geological Survey, P. O. Box 1347, Lara mie, Wyo ming 82073, U S A 6 Depart ment of Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of Ne w Mexico, Redondo Drive NE, Albuquerque, Ne w Mexico 87131, U S A C O R RESP O N DE N CE: aaslan @colorado mesa .edu 7 Ne w Mexico Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources, Ne w Mexico Tech, 801 Leroy Place, Socorro, Ne w Mexico 87801, U S A CI T A TI O N: Aslan, A., Boraas- Connors, M., Sprinkel, D. -

Mountain-Prairie Region 6 Overview of the Service’S Mountain-Prairie Region

U.S. U.S.Fish Fish & Wildlife & Wildlife Service Service Mountain-Prairie Region 6 Overview of the Service’s Mountain-Prairie Region Widgeon Pond at Red Rocks Lake National Wildlife Refuge / USFWS The Mountain-Prairie Region consists of federal agencies such as the Department Regional Demographics 8 states in the heart of the American of Defense. Energy development, ■ Land area: 737,884 square miles west including Colorado, Kansas, agricultural trends and urbanization all (468,573,000 acres) Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, exert influences on the Region’s ■ Population: 15,403,172 (Roughly 2.5 to South Dakota, Utah and Wyoming. The landscapes. 1 urban to rural ratio) region is defined by three distinct ■ Members of Congress: 37 landscapes. In the east lie the central Resource Facts and Figures ■ Federally Recognized Indian Tribes: 40 and northern Great Plains, primarily the ■ Approximately 5,751,358 acres ■ Public land: 137,024,000 acres (federal vast mixed- and short-grass prairies. To protected by the National Wildlife and state) the west rise the Rocky Mountains and Refuge System (NWRS), including ■ Wildlife-dependent recreation: the intermountain areas beyond the both fee title and easement lands. This 7,275,000 people* (hunting, fishing, and Continental Divide, including parts of includes 124 national wildlife refuges, wildlife watching) the sprawling Colorado Plateau and the 18 coordination areas, and numerous * USDA Economic Research Service Great Basin. The northeastern part of waterfowl production areas in 120 **FY 2011 National Survey of Fishing, the Region contains millions of shallow counties through Fiscal Year 2012. Hunting, and Wildlife-Associated wetlands known as the “prairie ■ 2,576,476 visitors to NWRS lands in Recreation potholes,” which produce a large portion Fiscal Year 2012. -

00364 Final Report 7-1-02

MIDDLE BOULDER CREEK WATER SOURCE MANAGEMENT WORK PLAN BOULDER, COLORADO Prepared by the Water Resources Staff of the Utilities Division of the city of Boulder, with support from: GEI Consultants, Inc. Brown & Caldwell Hydrosphere Resource Consultants ERO Resources Corp. Western Environmental Analysts GBSM Steven P. Walker Kris Kranzush Version 1, July 23, 2002 Project 00364 MIDDLE BOULDER CREEK WATER SOURCE MANAGEMENT WORK PLAN BOULDER, COLORADO July 23, 2002 Submitted to: City of Boulder 1739 Broadway Boulder, CO 80306 Prepared by: GEI Consultants, Inc. 6950 South Potomac Street, Suite 200 Englewood, CO 80112 (303) 662-0100 Project 00364 _______________________________________ Curtis A. Thompson, P.E. Project Manager _______________________________________ Richard A. Westmore, P.E. Senior Project Advisor GEI Consultants, Inc., Project 00364, 07/18/02 00364 Final Report (7-1-02).doc Version 1, June 20, 2002 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Background On March 7, 2001, the city of Boulder purchased Barker Dam, Barker Meadow Reservoir, the Barker Gravity Pipeline, Kossler Reservoir, the pipeline from Kossler Reservoir to Boulder Canyon Hydroelectric Plant, and the Boulder Canyon Hydroelectric Plant from Xcel Energy (Public Service Company of Colorado) for $12.4 million. Combined, the purchased facilities and the accompanying land constitute the Boulder Canyon Hydroelectric Project (Barker system). Boulder purchased the Boulder Canyon Hydroelectric Project using a portion of the proceeds from the sale of Windy Gap Project units in 1991. All remaining funds from the Windy Gap sale will be used to repair and upgrade the Barker system. The main purpose for the purchase of the these facilities was to enhance Boulder’s municipal water supply and to allow the city to make necessary repairs to the Barker system. -

Lake Granby Fishery Management Report Jon Ewert, Aquatic Biologist, Colorado Parks and Wildlife February 2019

Lake Granby Fishery Management Report Jon Ewert, Aquatic Biologist, Colorado Parks and Wildlife February 2019 Introduction Lake Granby, approximately 7,250 surface acres when full, is one of the largest coldwater reservoirs in the state. It is the main storage reservoir in the west slope portion of the Colorado-Big Thompson Project which supplies water to the northern Front Range through the Adams Tunnel at Grand Lake. It is a focal point of the Grand County tour- ism economy and offers many amenities. Recreational access is managed by the U.S. Forest Service as part of the Arapaho National Recreation Area. The recreational fishery of Granby is dominated by lake trout (aka mackinaw) and hosts the highest density of the species that has been documented in Colorado. Kokan- ee salmon have been stocked in Granby since 1951 to pro- vide recreational opportunity, a prey base to produce tro- phy lake trout, and spawning adults are captured annually to provide eggs for restocking. Rainbow trout of various sizes are also stocked and there is a moderate density of self-sustaining brown trout. Suckers and mottled sculpin Figure 1. Lake Granby are also present. Lake Granby also contains a dense population of mysis separate from the aggregate bag limit of other species. shrimp, which are an excellent prey source for smaller Due to reasons described above, the lake trout fishery in (<24”) lake trout. The high density of lake trout is a result Lake Granby is healthiest when a generous amount of har- of the availability of this prey base. However, the mysis vest is occurring. -

SURVEY of REAERATION NEEDS on BUREAU of RECLAMATION PROJECTS ,-->,-\ N Z G 3

PAP 2 HYDRAULICS BRANCH OFFICIAL FILE COPY c SURVEY OF REAERATION NEEDS ON BUREAU OF RECLAMATION PROJECTS ,-->,-\ N z g 3 by E. J. Carlson Hydraulics Branch Division of General Research Engineering and Research Center Bureau of Reclamation Denver, Colorado February 1972 OPTIONAL FORM NO. 10 MAY 1001 EDITION GSA FPMR (41 CFR) 101-11.0 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT Memorandum Memorandum Denver, Colorado TO Chief, Division of General Research, DATE: June 30, 1972 Regional Director, Region 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 FROM E. J. Carlson SUBJECT: Completion of Study Team Report The report, "Survey of Reaeration Needs on Bureau Projects," was prepared from data obtained mainly from Regional Personnel. Copies of the report are being furnished to all regional offices. By this memorandum regional offices are asked to review the report and make suggestions for changes and additions. The information may be helpful in starting projects which will be required in the near future to meet states' water quality standards. Problem areas in one region may serve as reminders for future problem areas in other regions. The Reaeration Research Program Management Team is available to assist Bureau offices in solving problems caused by oxygen deficiency in reser- voirs, lakes, streams,-canals, and aquifers. The information in the report will also be used by other public agencies and private companies and individuals. The report includes survey-type information and does not reflect policy of the Bureau. i Buy U.S. Savings Bonds Regularly on the Payroll Savings Plan SOIU-108 ACKNOWLEDGMENT The survey of reaeration needs on Bureau of Reclamation Projects was conducted in the Hydraulics Branch under the supervision of the Reaeration Research Program Management Team. -

Profiles of Colorado Roadless Areas

PROFILES OF COLORADO ROADLESS AREAS Prepared by the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region July 23, 2008 INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK 2 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS ARAPAHO-ROOSEVELT NATIONAL FOREST ......................................................................................................10 Bard Creek (23,000 acres) .......................................................................................................................................10 Byers Peak (10,200 acres)........................................................................................................................................12 Cache la Poudre Adjacent Area (3,200 acres)..........................................................................................................13 Cherokee Park (7,600 acres) ....................................................................................................................................14 Comanche Peak Adjacent Areas A - H (45,200 acres).............................................................................................15 Copper Mountain (13,500 acres) .............................................................................................................................19 Crosier Mountain (7,200 acres) ...............................................................................................................................20 Gold Run (6,600 acres) ............................................................................................................................................21 -

Code of Colorado Regulations

DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Division of Wildlife CHAPTER 1 FISHING 2 CCR 406-1 [Editor’s Notes follow the text of the rules at the end of this CCR Document.] ARTICLE I - GENERAL PROVISIONS #100 - DEFINITIONS See also 33-1-102, C.R.S and Chapter 0 of these regulations for other applicable definitions. A. "Artificial flies and lures" means devices made entirely of, or a combination of, natural or synthetic non-edible, non-scented (regardless if the scent is added in the manufacturing process or applied afterward), materials such as wood, plastic, silicone, rubber, epoxy, glass, hair, metal, feathers, or fiber, designed to attract fish. This definition does not include anything defined as bait in #100.B below. B. “Bait” means any hand-moldable material designed to attract fish by the sense of taste or smell; those devices to which scents or smell attractants have been added or externally applied (regardless if the scent is added in the manufacturing process or applied afterward); scented manufactured fish eggs and traditional organic baits, including but not limited to worms, grubs, crickets, leeches, dough baits or stink baits, insects, crayfish, human food, fish, fish parts or fish eggs. C. "Chumming" means placing fish, parts of fish, or other material upon which fish might feed in the waters of this state for the purpose of attracting fish to a particular area in order that they might be taken, but such term shall not include fishing with baited hooks or live traps. D. “Game fish” means all species of fish except prohibited nongame, endangered and threatened species, which currently exist or may be introduced into the state and which are classified as game fish by the Commission. -

Bent's Fort Teacher Resource Guide-Secondary

Annotated Resource Set (ARS) Bent’s Fort Teacher Resource Guide-Secondary Title / Content Area: Bent’s Fort-US History Developed by: Kelly Jones-Wagy Grade Level: 9-12 Contextual Paragraph Bent’s Fort in southeastern Colorado, built in 1833 by trader and rancher William Bent, was an important trading settlement in the 1830s. Located on the border of Mexico and US territory and in the heart of Native American country, Bent’s Fort was a hub of globalism, international trade, and international relations. Although Bent mysteriously destroyed it in 1852, the fort was rebuilt in 1976 and is now a National Historic Landmark. Bent’s Fort does not typically align with high school curriculum; however, it is an excellent introduction to the Sand Creek Massacre and Manifest Destiny. The Sand Creek Massacre took place on November 29, 1864, in southeastern Colorado. Colonel John Chivington (the hero of the Civil War Battle of Glorieta Pass) attacked an American Indian encampment made up largely of women and children from the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes. About 200 people were killed in the attack, and Chivington paraded body parts of the dead along the streets of Denver. In 1865 Congress led an investigation into the massacre, but Chivington never faced charges for his role. In addition to its connections to the events at Sand Creek, Bent’s Fort helped open up the American western frontier to settlement. It helped America bring forward the concept of Manifest Destiny. 1 Resource Set Title Primary Source Lesson Map of the upper Great The Dawes Act Johnson's new Ft. -

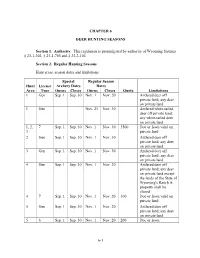

Deer Season Subject to the Species Limitation of Their License in the Hunt Area(S) Where Their License Is Valid As Specified in Section 2 of This Chapter

CHAPTER 6 DEER HUNTING SEASONS Section 1. Authority. This regulation is promulgated by authority of Wyoming Statutes § 23-1-302, § 23-1-703 and § 23-2-104. Section 2. Regular Hunting Seasons. Hunt areas, season dates and limitations. Special Regular Season Hunt License Archery Dates Dates Area Type Opens Closes Opens Closes Quota Limitations 1 Gen Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 20 Antlered deer off private land; any deer on private land 1 Gen Nov. 21 Nov. 30 Antlered white-tailed deer off private land; any white-tailed deer on private land 1, 2, 7 Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 30 3500 Doe or fawn valid on 3 private land 2 Gen Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 30 Antlered deer off private land; any deer on private land 3 Gen Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 30 Antlered deer off private land; any deer on private land 4 Gen Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 20 Antlered deer off private land; any deer on private land except the lands of the State of Wyoming's Ranch A property shall be closed 4 7 Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 20 300 Doe or fawn valid on private land 5 Gen Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 20 Antlered deer off private land; any deer on private land 5 6 Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 20 200 Doe or fawn 6-1 6 Gen Sep. 1 Sep. 30 Nov. 1 Nov. 20 Antlered deer off private land; any deer on private land 7 Gen Sep. -

Colorado River Slideshow Title TK

The Colorado River: Lifeline of the Southwest { The Headwaters The Colorado River begins in the Rocky Mountains at elevation 10,000 feet, about 60 miles northwest of Denver in Colorado. The Path Snow melts into water, flows into the river and moves downstream. In Utah, the river meets primary tributaries, the Green River and the San Juan River, before flowing into Lake Powell and beyond. Source: Bureau of Reclamation The Path In total, the Colorado River cuts through 1,450 miles of mountains, plains and deserts to Mexico and the Gulf of California. Source: George Eastman House It was almost 1,500 years ago when humans first tapped the river. Since then, the water has been claimed, reclaimed, divided and subdivided many times. The river is the life source for seven states – Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming – as well as the Republic of Mexico. River Water Uses There are many demands for Colorado River water: • Agriculture and Livestock • Municipal and Industrial • Recreation • Fish/Wildlife and Habitat • Hydroelectricity • Tribes • Mexico Source: USGS Agriculture The Colorado River provides irrigation water to about 3.5 million acres of farmland – about 80 percent of its flows. Municipal Phoenix Denver About 15 percent of Colorado River flows provide drinking and household water to more than 30 million people. These cities include: Las Vegas and Phoenix, and cities outside the Basin – Denver, Albuquerque, Salt Lake City, Los Angeles, San Diego and Tijuana, Mexico. Recreation Source: Utah Office of Tourism Source: Emma Williams Recreation includes fishing, boating, waterskiing, camping and whitewater rafting in 22 National Wildlife Refuges, National Parks and National Recreation Areas along river.