To Evaluate the Support Required for Staff In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 in – Handbook-ANNEXURE K

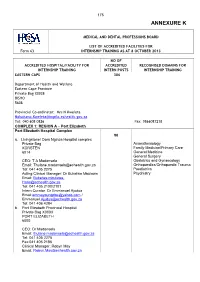

175 ANNEXURE K MEDICAL AND DENTAL PROFESSIONS BOARD LIST OF ACCREDITED FACILITIES FOR Form 63 INTERNSHIP TRAINING AS AT 8 OCTOBER 2013 NO OF ACCREDITED HOSPITAL/FACILITY FOR ACCREDITED RECOGNISED DOMAINS FOR INTERNSHIP TRAINING INTERN POSTS INTERNSHIP TRAINING EASTERN CAPE 306 Department of Health and Welfare Eastern Cape Province Private Bag X0038 BISHO 5608 Provincial Co-ordinator: Mrs N Kweleta [email protected] Tel: 040 608 0826 Fax: 0866087218 COMPLEX 1: REGION A – Port Elizabeth Port Elizabeth Hospital Complex 90 a. Livingstone/ Dora Nginza Hospital complex Private Bag Anaesthesiology KORSTEN Family Medicine/Primary Care 6014 General Medicine General Surgery CEO: T A Madonsela Obstetrics and Gynaecology Email: [email protected] Orthopaedics/Orthopaedic Trauma Tel: 041 405 2275 Paediatrics Acting Clinical Manager: Dr Bukelwa Mbulawa Psychiatry Email: Bukelwa.mbulawa- [email protected] Tel: 041 405 2100/2101 Intern Curator: Dr Emmanuel Ajudua Email:[email protected] / [email protected] Tel: 041 406 4284 b. Port Elizabeth Provincial Hospital Private Bag X0003 PORT ELIZABETH 6000 CEO: Dr Madonsela Email: [email protected] Tel: 041 405 2275 Fax:041 405 2186 Clinical Manager: Robyn May Email: [email protected] 176 NO OF ACCREDITED HOSPITAL/FACILITY FOR ACCREDITED RECOGNISED DOMAINS FOR INTERNSHIP TRAINING INTERN POSTS INTERNSHIP TRAINING Uitenhage Provincial Hospital Private Bag X36 30 Anaesthesiology UITENHAGE Family Medicine/Primary Care 6630 General Medicine General Surgery CEO: Ms Klassen Obstetrics and Gynaecology Email: [email protected] Orthopaedics/Orthopaedic Trauma Tel: 041 995 1130 Paediatrics Fax: 041 9661413 Psychiatry Clinical Manager: Dr G B Walsh Email: [email protected] Tel: 041 995 1130 Intern Curator: Dr F Zietsman Email: [email protected] Tel: 041 995 1356 COMPLEX 2: REGION B – None COMPLEX 3: REGION C – East London East London Hospital Complex 108 a. -

The Knowledge of the Registration of the Role of the Doula in the Facilitation of Natural Child Birth

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Stellenbosch University SUNScholar Repository THE KNOWLEDGE OF THE REGISTRATION OF THE ROLE OF THE DOULA IN THE FACILITATION OF NATURAL CHILD BIRTH Nonkululeko Veronica Kaibe Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Nursing in the Faculty of Health Sciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Dr ELD Boshoff March 2011 DECLARATION By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. ___________________________ __________________________ Nonkululeko Veronica Kaibe Date Copyright © 2011 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My understanding of the needs of mothers’ during labour developed with my experience in teaching student nurses on training midwifery course, both the 4 year diploma and the one- year diploma. Working as a registered midwife for the past 14 years also made me realise that there was a need for ongoing support for a woman giving birth. I would like to express my thanks and gratitude to the following people: God Almighty for the strength and wisdom he gave me during this study My friends for their continuous support and encouragement My supervisor, Dr Dorothy Boshoff, for her patience, guidance and understanding; I would never have managed without her. -

Clinical Outcomes of Children Operated for Rheumatic Valvular Heart Disease in a Tertiary Hospital in South Africa

Academic Journal of Pediatrics & Neonatology ISSN 2474-7521 Research Article Acad J Ped Neonatol Volume 5 Issue 5 - September 2017 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Zongezile Masonwabe Makrexeni DOI: 10.19080/AJPN.2017.05.555728 Clinical Outcomes of Children Operated for Rheumatic Valvular Heart Disease in A Tertiary Hospital in South Africa ZM Makrexeni* and L Pepeta Faculty of Health Sciences, Nelson Mandela University, Port Elizabeth, South Africa Submission: August 08, 2017; Published: September 11, 2017 *Corresponding author: Zongezile Masonwabe Makrexeni, Paediatric Cardiology Unit, Walter Sisulu University, Port Elizabeth, South Africa, 6005, Tel: ; Email: Background mitral commissurotomy as the preferred treatment of choice for Acute Rheumatic Fever (ARF) is a post infectious, non- rheumatic mitral stenosis in appropriately selected candidates suppurative sequel of pharyngeal infection with streptococcal [11]. pyogens, or group a beta hemolytic streptococcus [1]. Rheumatic fever occurs in 3-4% of untreated group a streptococcal Retrograde (Trans arterial) and antegrade (transvenous) pharyngitis. Devastating complications of Rheumatic Heart approaches to percutaneous mitral balloon valvuloplasty have Disease (RHD) include severe valve regurgitation, heart failure, been described. Currently, the antegrade approach with trans- strokes and infective endocarditis, usually affecting both younger schools going and economically active, child bearing members of through the femoral vein; however, the jugular venous approach septal catheterization is more widely used. It is usually performed society [2]. has also been described [11]. Rheumatic Heart Disease (RHD) is of global health Mitral valve repair is recommended over mitral valve replacement in the majority of patients with severe chronic mitral RHD, with almost 80% of those residing in low and middle income regurgitation who require surgery. -

Dora Nginza Hospital Advertisement Posted on 19

EASTERN CAPE DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH PORT ELIZABETH PUBLIC HOSPITALS (DNH) The Department of Health is registered with the Department of Labour as a designated Employer and the filling of the following posts will be in line with the Employment Equity Act (including people with disabilities) DORA NGINZA HOSPITAL ADVERTISEMENT POSTED ON 19 JUNE 2016 CLOSING DATE 04 JULY 2016 DORA NGINZA HOSPITAL ENQUIRIES: Mr ZW MBUZI TEL NO (041) 406 4421 APPLICATIONS: Must be submitted to Human Resource Office ,Dora Nginza Hospital, Private Bag X 11951, Algoa Park, Port Elizabeth 6005 or Hand Delivery Administration Block, 1ST Floor, Spondo Street, Zwide POST/1: CLINIICAL GOVERNANCE MANAGER: CLINICAL UNIT: MEDICAL GRADE 1 REF NO: CMM/CEO/TTBH/2016 CENTRE: DORA NGINZA HOSPITAL SALARY LEVEL: OSD SALARY SCALE: R981 093-R1 088 862 REQUIREMENTS Appropriate qualification that allows registration with Health Professional Council of South Africa(HPCSA-2016) as a Medical Practitioner ( Independent practice).A minimum of 3-5 years appropriate experience after registration with the HPCSA as a Medical Practitioner. Valid driver’s license( Code B/EB).Appropriate and proven managerial experience in an academic and/or health care environment, showing strong leadership strategic and operational skills in managing clinical services departments at strategic, operational and contingency levels. Knowledge and proven managerial experience with regard to Human , Financial and Physical resources management in a clinical health setting and extensive knowledge of National, Provincial and Institutional health delivery system, policies and law, governing resources allocations as well as medico-legal matters. Proven skills in quality improvement strategies and implementation thereof, analytical and innovative thinking and problem solution relevant to an Academic Health Care setting in the Public Health arena. -

Improved Systems Access Pharmaceuticals Andservices

Systems for Improved Access toPharmaceuticals and Services Improved Access. Improved Services. Better Health Outcomes. Annual Report: Program Year 3 October 2013–September 2014 Cover Photo Credit: Warren Zelman 2 This report is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the US Agency for International Development (USAID), under the terms of cooperative agreement number AID-OAA-A-11-00021. The contents are the responsibility of Management Sciences for Health and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. About SIAPS The goal of the Systems for Improved Access to Pharmaceuticals and Services (SIAPS) Program is to assure the availability of quality pharmaceutical products and effective pharmaceutical services to achieve desired health outcomes. Toward this end, the SIAPS result areas include improving governance, building capacity for pharmaceutical management and services, addressing information needed for decision-making in the pharmaceutical sector, strengthening financing strategies and mechanisms to improve access to medicines, and increasing quality pharmaceutical services. Recommended Citation This report may be reproduced if credit is given to SIAPS. Please use the following citation. Systems for Improved Access to Pharmaceuticals and Services. 2014. Systems for Improved Access to Pharmaceutical Services Annual Report: Project Year 3, October 2013–September 2014. Submitted to the US Agency for International Development by the Systems for Improved Access to Pharmaceuticals -

Rapid Testing for Respiratory Syncytial Virus in a Resource-Limited Paediatric Intensive Care Setting

African Journal of Laboratory Medicine ISSN: (Online) 2225-2010, (Print) 2225-2002 Page 1 of 5 Brief Report Rapid testing for respiratory syncytial virus in a resource-limited paediatric intensive care setting Authors: We analysed the performance characteristics of the respiratory syncytial virus lateral flow 1,2,3 Howard Newman rapid antigen assay in use when compared to a multiplex polymerase chain reaction for Donald Tshabalala4,5 Sikhumbuzo Mabunda6,7 detection of respiratory viruses. The study was conducted at a tertiary paediatric hospital in Nokwazi Nkosi2,8 Port Elizabeth, South Africa, from 01 January 2017 to 31 December 2018. We found the clinical Candice Carelson1 sensitivity (36.8%) of the rapid test to be too low for routine diagnostic use. Knowledge of assay performance characteristics of rapid tests are important for appropriate interpretation of Affiliations: 1National Health Laboratory rapid test results. Service, Virology, Port Keywords: respiratory syncytial virus; rapid antigen tests; respiratory viruses; respiratory Elizabeth, South Africa multiplex polymerase chain reaction; assay performance characteristics. 2Department of Pathology, Division of Medical Virology, Stellenbosch University, Cape Town, South Africa Introduction Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection is a common cause of casualty visits and hospital 3Faculty of Health Sciences, admissions in infants.1,2,3,4 In 2005, a meta-analysis reported that between 66 000 and 160 000 Nelson Mandela University, children under age 5 years died of RSV infection -

Abstracts Book

Abstracts 5th edition pg. 0 Committees EiP Board Chair: Dimitri A. Christakis, MD, MPH, George Adkins Professor of Pediatrics, University of Washington & Director, Center for Child Health, Behavior, and Development, Seattle Children’s Research Institute, USA Members (listed in alphabetical order): Yagob AL-Mazrou, MB ChB, DCH, PhD, FRCGPDr , Secretary General, Council of Health Services, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia Frederick A. Connell, MD, MPH , Professor & Associate Dean, School of Public Health, University of Washington, Seattle, USA Terence Stephenson, Nuffield Professor of Child Health, Institute of Child Health, UCL & Chairman, Academy of Royal Medical Colleges, UK Diego van Esso, MD, Primary Care Paediatrician, Primary Care Centre "Pare Claret", Institut Catala De La Salut, Barcelona, Spain pg. 1 EiP 2013 Steering Committee Co-Chairs: Dimitri A. Christakis, MD MPH, George Adkins Professor of Pediatrics, University of Washington & Director, Center for Child Health, Behavior, and Development, Seattle Children’s Research Institute, USA Edward S. Ogata, MD, MBA, CPHRM, Chief Medical Officer,Sidra Medical and Research Center, Doha, Qatar Members (listed in alphabetical order): Ahmed Alhammadi, MD, FRCPC, Academic Pediatrics Hospitalist, Head of General Pediatrics Division, Hamad Medical Corporation, Qatar Abdulla Mohd Essa Al Kaabi, MD, FAAP, FRCPC, Executive Vice Chief Medical Officer, Sidra Medical and Research Center, Doha, Qatar Stefano del Torso, MD, Chairman, European Academy of Paediatrics Research in Ambulatory Setting Network (EAPRASnet) & Primary Care Paediatrician, Padova, Italy Mohammad Janahi, MD, FAAP, Chairman, Department of Pediatrics & Head, Pediatric Infectious Diseases & Associate Professor, Clinical Pediatrics, Weill-Cornell Medical College, Doha, Qatar Jonathan D. Klein, MD, MPH, FAAP, Associate Executive Drector, American Academy of Pediatrics, USA Gerald M. -

Health Professions Act: List of Approved Facilities for the Purposes

STAATSKOERANT, 16 OKTOBER 2013 No. 36936 39 No. 791 16 October 2013 HEALTH PROFESSIONS ACT, 1974 (ACT NO. 56 OF 1974) LIST OF APPROVED FACILITIES FOR THE PURPOSES OF PERFORMING COMMUNITY SERVICE BY MEDICAL PRACTITIONERS IN THE YEAR 2014 The Minister of Health has, in terms of regulation 5.1 of the Regulations relating to Performance of Community Service by Persons Registering in terms of the Health Professions Act, 1974 (Act No. 56 of 1974), listed the following approved facilities for purposes of the profession of medicine. PROVINCE REGION/DISTRICT FACILITY EASTERN CAPE Alfred Nzo Khotsong Hospital* Madzikane kaZulu Hospital ** Umzimvubu Cluster Mt Ayliff Hospital** Taylor Bequest Hospital* (Matatiele) Amathole Bhisho CHH Cathcart Hospital * Amahlathi/Buffalo City Cecilia Makiwane Hospital Cluster Dimbaza CHC Duncan Village Day Hospital Empilweni Gompo CHC Fort Grey TB Hospital Frere Hospital Grey Hospital * Komga Hospital Nkqubela TB Hospital Nompumelelo Hospital* SS Gida Hospital* Stutterheim FPA Hospital* Mnquma Sub-District Butterworth Hospital* Nqgamakwe CHC* Nkonkobe Sub-District Adelaide FPA Hospital Tower Hospital* Victoria Hospital * Mbashe /KSD District Elliotdale CHC* Idutywa CHC* Madwaleni Hospital* Chris Hani All Saints Hospital** Engcobo/IntsikaYethu Cofimvaba Hospital** Martjie Venter FPA Hospital This gazette is also available free online at www.gpwonline.co.za 40 No. 36936 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 16 OCTOBER 2013 Sub-District Mjanyana Hospital * InxubaYethembaSub-Cradock Hospital** Wilhelm Stahl Hospital** District Inkwanca -

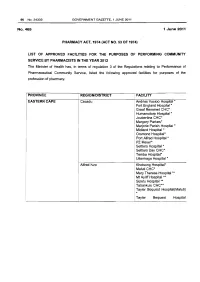

Health Professions Act: List of Approved Facilities for Community Service by Pharmacists in 2012

96 No.34332 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 1 JUNE 2011 No.465 1 June 2011 PHARMACY ACT, 1974 (ACT NO. 53 OF 1974} LIST OF APPROVED FACILITIES FOR THE PURPOSES OF PERFORMING COMMUNITY SERVICE BY PHARMACISTS IN THE YEAR 2012 The Minister of Health has, in terms of regulation 3 of the Regulations relating to Performance of Pharmaceutical Community Service, listed the following approved facilities for purposes of the profession of pharmacy. PROVINCE REGION/DISTRICT FACILITY EASTERN CAPE Cacadu Andries Vosloo Hospital * Fort England Hospital* Graaf Reneinet CHC* Humansdorp Hospital * Joubertina CHC* Margery Parkes* Marjorie Parish Hospital* Midland Hospital * Orsmond Hospital* Port Alfred Hospital * PZ Meyer* Settlers Hospital * Settlers Day CHC* Temba Hospital• Uitenhage Hospital * Alfred Nzo Khotsong Hospital• Maluti CHC* Mary Theresa Hospital .... ! Mt Ayliff Hospital ** · Sipetu Hospital •• Tabankulu CHC*• Tayler Bequest Hospitai(Maluti) * Tayler Bequest Hospital STAATSKOERANT, 1 JUNIE 2011 No. 34332 97 (Matatiele )"' Chris Hani All Saints Hospital ..... Cala Hospital ** Cofimvaba Hospital ** Cradock Hospital ** Elliot Hospital ... Frontier Hospital * Glen Grey Hospital * Mjanyana Hospital ** NgcoboCHC* Ngonyama CHC* Nomzamo CHC* Sada CHC* Thornhill CHC* Wilhelm Stahl Hospital ..... ZwelakheDalasile CHC* Nelson Mandala Dora Nginza Hospital Elizabeth Donkin Hospital Jose Pearson Santa Hospital Kwazakhele Day Clinic Laetitia Bam CH C Livingstone Hospital Motherwell CHC New Brighton CHC PE Pharmaceutical Depot PE Provincial Hospital Amathole Bedford Hospital Bhisho Hospital Butterworth Hospital Cecilia Makiwane Hospital Cathcart Hospital Dimbaza CHC Duncan Village Day CHC Dutywa CHC Empilweni Gompo CHC Fort Beauford Hospital Fort Grey Hospital Frere Hospital Grey Hospital Middledrift CHC Nontyatyambo CHC Nompomelelo Hospital Ngqamakwe CHC SS Gida Hospita Tafalofefe Hospital Tower Hospital Victoria Hospital Winterberg Hospital Willowvale CHC 98 No. -

Health Professions Act: List of Approved Facilities for Purposes Of

40 No. 35624 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 27 AUGUST 2012 No. 676 27 August 2012 HEALTH PROFESSIONS ACT, 1974 (ACT NO. 56 OF 1974) LIST OF APPROVED FACILITIES FOR THE PURPOSES OF PERFORMING COMMUNITY SERVICE BY MEDICAL PRACTITIONERS IN THE YEAR 2013 The Minister of Health has, in terms of regulation 5.1 of the Regulations relating to Performance of Community Service by Persons Registering in terms of the Health Professions Act, 1974 (Act No. 56 of 1974), listed the following facilities for purposes of the profession of medicine. PROVINCE REGION/DISTRICT FACILITY EASTERN CAPE Alfred Nzo Khotsong Hospital* Madzikane kaZulu Hospital ** Umzimvubu Cluster Mt Ayliff Hospital ** Taylor Bequest Hospital* (Matatiele) Amato le Cathcart Hospital * Cecilia Makiwane Hospital Amahlathi/Buffalo City Dimbaza CHC Cluster Fort Grey TB Hospital Grey Hospital * Komga Hospital Nkqubela TB Hospital Nompumelelo Hospital* SS Gida Hospital* Stutterheim FPA Hospital* Mnquma Sub-District Butterworth Hospital* Nqgamakhwe CHC* Nkonkobe Sub-District Adelaide FPA Hospital Tower Hospital* Victoria Hospital * Mbashe /KSD District Elliotdale CHC* Idutywa CHC* Madwaleni Hospital* Zitulele Hospital * Chris Hani All Saints Hospital ** Cofimvaba Hospital ** Engcobo/IntsikaYethu Martjie Venter FPA Hospital Sub-District Mjanyana Hospital * STAATSKOERANT, 27 AUGUSTUS 2012 No. 35624 41 lnxubaYethemba Sub-Cradock Hospital ** Wilhelm Stahl Hospital ** District Inkwanca Molteno FPA Hospital Lukhanji Frontier Hospital* Hewu Hospital * Komani Hospital* Sakhisizwe/Emalahleni Cala Hospital ** Dordrecht FPA Hospital Glen Grey Hospital ** Indwe FPA Hospital Ngonyama CHC* Nelson Mandela Metro Dora Nginza Hospital Empilweni TB Hospital PE Metro Jose Pearson TB Hospital Orsmond TB Hospital Letticia Barn CHC PE Provincial Uitenhage Hospital Kouga Sub-District Humansdorp Hospital BJ Voster FPA Hospital O.R.Tambo Dr Lizo Mpehle Memorial Hospital ** Nessie Knight Hospital ** Mhlontlo Sub-District Qaukeni North Sub-Greenville Hospital ** Holly Cross Hospital ** District Isipethu Hospital* Port St Johns CHC* St. -

Port Elizabeth's Tertiary Care Reaches Crisis Point

Izindaba Port Elizabeth’s tertiary care reaches crisis point district hospitals and clinics that rely on them exclusively for referral – with potentially fatal effects when inter-disciplinary care is required. When Dr Siva Pillay was shown the letters by Izindaba, he expressed the ‘utmost respect’ for ‘most’ of the specialists who were ‘fighting a genuine battle that needs to be fought’. However, he said, had they spoken to him, they would have learnt that he had smoothed out the human resource process ‘so that we can now fast-track appointments’, and that his recent intervention with national treasury had led to a resetting of his health budget to include the R1.5 billion in overdraft and unauthorised expenditure previously earmarked for immediate repayment. In terms of recent political manoeuvring, a provincial co-ordinating and monitoring team now vets all appointments and provincial treasury has taken over the PERSAL (personnel L - R: Dr Lungile Pepeta, Paediatric Chief at Dora Nginza Hospital, Dr Basil Brown, Cardiology Chief salary) function and, said Pillay: ‘They don’t at Port Elizabeth Provincial Hospital and Professor Sats Pillay, Head of Surgery at Livingstone Hospital, understand the urgency of it’.1 at their ‘rebel’ Port Elizabeth press conference on 26 June this year. Dual loyalties again to Almost across disciplines, health care in country-wide since. Eastern Cape Health the fore the Port Elizabeth Provincial Hospital Director General, Dr Siva Pillay, angered Professor Sats Pillay, Head of Surgery at Complex (PEPHC) has -

Cohsasa News Sept 06

CohsasaThe Newsletter The Council for Health Service Accreditation of Southern Africa TECHNOLOGY UPDATE OCTOBER 2006 New information system is a treasure map COHSASA – in partnership with Xylaco Software – has developed a unique application, which will provide a 360-degree view of strengths, weaknesses and Ten South African urgent improvements needed in health facilities enrolled in COHSASA’s quality hospices accredited improvement and accreditation programmes. Ten hospices in the country, all members of the Hospice Palliative Care Association of Examining 37 areas of operation and measuring both clinical and non- South Africa, have been accredited clinical performance indicators, the new database, migrated from for two years, having met the COHSASA’s multiple legacy databases, will be able to provide professional quality standards clients with quick and easy access to a treasure trove of of COHSASA. information about their hospitals. A total of 47 members of Want to know how your hospital shapes up with regard to the Association entered the infection control? Get your access code, connect on-line and accreditation programme. the COHSASA information system will tell you exactly how Grahamstown Hospice you stand against professional standards, how various was the first to be departments associated with infection control are managing, accredited, followed by what criteria they are meeting and urgent deficiencies that nine others, which have met must be promptly addressed. stringent requirements for Moreover, if you are in the COHSASA Facilitated REWARDING QUALITY: Chairman of COHSASA, the provision of palliative care. Accreditation Programme, you can monitor staff progress and Albert Ramukumba, hands over the accreditation award to the Nursing Services Director of St Francis They were rated on standards pinpoint the bottlenecks and delays.