State of the Unions PAPER BRIEFING How to Restore Free Association and Expression, Combat Extremism and Make Student Unions Effective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Ii ©[2014] Susanna Polihros ALL RIGHTS RESERVED](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6761/ii-%C2%A9-2014-susanna-polihros-all-rights-reserved-56761.webp)

Ii ©[2014] Susanna Polihros ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

[2014] Susanna Polihros ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii BATH, CITY UNDER SIEGE: ARCHITECTURE STRUGGLING TO REMAIN WED TO NATURE By SUSANNA POLIHROS A thesis submitted to the Graduate School – New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Art History written under the direction of Dr. Tod Marder and approved by Dr. Katharine Woodhouse-Beyer Dr. Archer St. Clair-Harvey _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey January 2014 iv ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS: Bath, City Under Siege: Architecture Struggling to Remain Wed to Nature By SUSANNA POLIHROS Thesis Director: Dr. Tod Marder This thesis examines current historic preservation and conservation efforts for Bath, England’s only complete UNESCO World Heritage city, where urban and commercial development remain a controversial threat to its status. This is best represented by the opposing views of the Bath Preservation Trust and the Bath & North East Somerset Council. While the Trust stands as a supporter of saving Georgian Bath, the Council continues to sacrifice precious greenbelt areas and historic buildings for the purpose of attracting tourists and prospective residents. Both organizations are extensively examined in order to better comprehend Bath’s future. Although no definite answer can be reached at this point in time, besides establishing balance between old and new architecture, examining social and political issues in this city demonstrates that there is a serious need for legal intervention to prevent further destruction to a past way of life so that the modern world can emerge. Areas explored include the conserved Roman Baths, the recent developments of SouthGate and the Western Riverside Development, the conserved Beckford’s Tower and the demolished Gasholder. -

Nus Conference Report

Council Agenda item 12 28th April 2008 Imperial College Union NUS CONFERENCE REPORT A note by the President Introduction Nine students of Imperial College gave up 3 days that they will never see again to represent the views of this Union at NUS Conference in Blackpool. The purpose of this report is to provide you with a brief overview of how we got on and to give you a flavour of the sort of things that go on at this bizarre meeting. Our delegation Eight delegates were elected by cross campus ballot along with the 2008/09 Sabbatical Officers to attend conference. I attended as ex-officio delegation leader as per the NUS and ICU constitutions. 2 of the delegates elected were unable to attend due to a change in circumstances. One of these was replaced by Jess Marley and this substitution was reported to the last Council. Another replacement had to be found around 18 hours before the registration deadline closed so after a lot of scrambling around Alex Grisman kindly agreed to join our delegation. This meant that we did not have any vacancies and thus our final delegation was • Stephen Brown • Ashley Brown • Kirsty Patterson • Alex Grisman • Jess Marley • Liz Hyde • Jen Morgan • Victoria Gibbs • Camilla Royle Conduct of delegates Eight delegates were flawless and they are to be congratulated on attending a meeting which ran on to 11pm at night. 1 delegate however disobeyed the Union Constitution and the democratically decided will of Union Council by voting against the NUS governance reforms on behalf of Student Respect, a hard left political grouping active within NUS and will now be subject to a disciplinary motion at the next meeting of Council. -

UA/1718/001 Durham Students' Union Assembly Agenda Tuesday, 24 October 2017

UA/1718/001 Durham Students’ Union Assembly Agenda Tuesday, 24 October 2017– 19:00, CG93 (Scarborough lecture theatre, Chemistry department) Time Subject Who Paper 19:00- A. Welcome President 19:01 19:01- B. Apologies for absence and President 19:03 Conflicts of interest 19:03- C. Minutes of the meeting on 16 June 2017 President UA/1617/063 19:05 including ratification of old business Routine Business 19:05- D. Election of Chair President UA/1718/002 19:15 19:15- E. Election of Vice Chair Chair 19:20 19:20- F. Election of Assembly/Committee Members Chair UA/1718/003 19:40 19:40- G. Sharing of Officer Objectives Sabbatical Officers UA/1718/004 19:55 Items for Discussion 19:55- H. Motion: Free Education PG and UG Academic UA/1718/005 20:15 Officers 20:15- I. Policy: Dunelm House President UA/1718/006 20:25 20:25- J. Policy: Naming the 17th College Sabbatical Officer s UA/1718/007 20:35 20:35 K. Open Discussion Chair 20:45 Other Business 20:45- L. Questions to Officers 20:55 For Your Information 20:55- M. Update on Voter Registration Policy Opportunities Officer UA/1718/008 21:00 Next meeting will be 7 December 2017, ER142 Agenda closes (so papers must be in) 27 November 2017 at 17:00. Assembly is committed to making its meetings accessible to persons with disabilities. If you consider yourself to have any access or reasonable adjustment needs, please contact the Union President at [email protected] at least 2 days in advance to make arrangements. -

Contemporary Left Antisemitism

“David Hirsh is one of our bravest and most thoughtful scholar-activ- ists. In this excellent book of contemporary history and political argu- ment, he makes an unanswerable case for anti-anti-Semitism.” —Anthony Julius, Professor of Law and the Arts, UCL, and author of Trials of the Diaspora (OUP, 2010) “For more than a decade, David Hirsh has campaigned courageously against the all-too-prevalent demonisation of Israel as the one national- ism in the world that must not only be criticised but ruled altogether illegitimate. This intellectual disgrace arouses not only his indignation but his commitment to gather evidence and to reason about it with care. What he asks of his readers is an equal commitment to plumb how it has happened that, in a world full of criminality and massacre, it is obsessed with the fundamental wrongheadedness of one and only national movement: Zionism.” —Todd Gitlin, Professor of Journalism and Sociology, Columbia University, USA “David Hirsh writes as a sociologist, but much of the material in his fascinating book will be of great interest to people in other disciplines as well, including political philosophers. Having participated in quite a few of the events and debates which he recounts, Hirsh has done a commendable service by deftly highlighting an ugly vein of bigotry that disfigures some substantial portions of the political left in the UK and beyond.” —Matthew H. Kramer FBA, Professor of Legal & Political Philosophy, Cambridge University, UK “A fierce and brilliant rebuttal of one of the Left’s most pertinacious obsessions. What makes David Hirsh the perfect analyst of this disorder is his first-hand knowledge of the ideologies and dogmata that sustain it.” —Howard Jacobson, Novelist and Visiting Professor at New College of Humanities, London, UK “David Hirsh’s new book Contemporary Left Anti-Semitism is an impor- tant contribution to the literature on the longest hatred. -

University of Glasgow, Glasgow, Scotland

UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN EAU CLAIRE CENTER FOR INTERNATIONAL EDUCATION Study Abroad UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW, GLASGOW, SCOTLAND 2020 Program Guide ABLE OF ONTENTS Sexual Harassment and “Lad Culture” in the T C UK ...................................................................... 12 Academics .............................................................. 5 Emergency Contacts ...................................... 13 Pre-departure Planning ..................................... 5 911 Equivalent in the UK ............................... 13 Graduate Courses ............................................. 5 Marijuana and other Illegal Drugs ................ 13 Credits and Course Load .................................. 5 Required Documents .......................................... 14 Registration at Glasgow .................................... 5 Visa ................................................................... 14 Class Attendance ............................................... 5 Why Can’t I fly through Ireland? ................... 14 Grades ................................................................. 6 Visas for Travel to Other Countries .............. 14 Glasgow & UWEC Transcripts ......................... 6 Packing Tips ........................................................ 14 UK Academic System ....................................... 6 Weather ............................................................ 14 Semester Students Service-Learning ............. 9 Clothing............................................................ -

Impact Report 2016/17

1 Oxford University Students’ Union Impact Report 2016-2017 Introduction The past year has in many ways been a transformational one for the Students’ Union. A new sabbatical team, a new CEO, eight new staff and an upcoming new Organisational Strategy have all meant that this year has had to have a focus on meaningful introspection. However, this has not held us back in our outward student engagement, and indeed has provided an opportunity to truly refocus, rebrand and reposition ourselves within the Oxford student and community landscape. In the last six months, the Students’ Union has engaged more students, in more ways and across more demographics, than ever before. Some of our achievements include: • Running a community festival with a footfall of ~2000 people • Our biggest ever Teaching Awards with 895 nominations and 25 award-winners • Elections with the highest turnout in three years (more than doubling graduate turnout), and • A sustained student wellbeing and stress relief programme reaching hundreds of students a week throughout Trinity Term. Our vision of an SU that is valued by every single student at Oxford is closer than ever, and we now have a plan to close that last gap. In addition to increased outreach and broader student engagement, OUSU retains a strong commitment to its core educational, representative, and campaigning mission. We have built on our heritage as a Union that empowers, enables, and channels student interests to improve our University through dedicated collaboration and constructive criticism. On education, a high-profile campaign against the Higher Education and Research Bill contributed to planned fee increases for on course students being dropped and over 70 members of the House of Lords being directly lobbied to amend the bill. -

TUC Congress Guide 2016

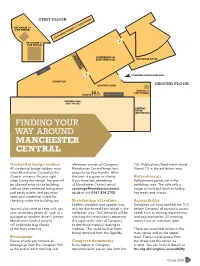

➤ (FORCHARTER FRINGE) 4 CONFERENCE IN EXCHANGE HALL EXCHANGE FOYER CAFE ➤ ➤ CONGRESS MAIN ENTRANCE FIRST FLOOR EXHIBITION CHARTER FOYER EXCHANGE 10 (FOR FRINGE) CENTRAL 8 (FOR FRINGE) TOILETS REGISTRATION EXCHANGE ROOMS 1-7 (FOR FRINGE) ➤ CENTRAL HALL EXCHANGE 11 (NOT IN USE) (FOR FRINGE) CENTRAL FOYER (NOT IN USE) (FORCHARTER FRINGE) 4 CONFERENCE IN EXCHANGE HALL EXCHANGE FOYER CAFE ➤ ➤ CONGRESS MAIN ENTRANCE EXHIBITION GROUND FLOOR CHARTER FOYER EXCHANGE 10 (FOR FRINGE) CENTRAL 8 (FOR FRINGE) TOILETS REGISTRATION EXCHANGE ROOMS 1-7 (FOR FRINGE) CENTRAL HALL EXCHANGE 11 (NOT IN USE) (FOR FRINGE) CENTRAL FOYER (NOT IN USE) FINDING YOUR WAY AROUND MANCHESTER CENTRAL Credential badge holders afternoon session of Congress. TUC Publications/Bookmarks stand All credential badge holders must Manchester Central keeps lost (Stand 11) in the exhibition area. enter Manchester Central by the property for two months. After Charter entrance (to your right this time it is given to charity. Refreshments when facing the venue). No-one will If you have lost something Refreshment points are in the be allowed entry to the building at Manchester Central, email exhibition area. The café sells a without their credential being worn concierge@manchestercentral. range of food and drink including and easily visible; and you must co.uk or call 0161 834 2700. hot meals and snacks. keep your credential visible for checking within the building too. Distribution of leaflets Accessibility Leaflets, booklets and appeals may Delegates will have notified the TUC You will also need to keep with you only be distributed from stands in the before Congress of particular access your secondary photo ID, such as a exhibition area. -

Framing Youth Suicide in a Multi-Mediated World: the Construction of the Bridgend Problem in the British National Press

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Akrivos, Dimitrios (2015). Framing youth suicide in a multi-mediated world: the construction of the Bridgend problem in the British national press. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/13648/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] FRAMING YOUTH SUICIDE IN A MULTI-MEDIATED WORLD THE CONSTRUCTION OF THE BRIDGEND PROBLEM IN THE BRITISH NATIONAL PRESS DIMITRIOS AKRIVOS PhD Thesis CITY UNIVERSITY LONDON DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES 2015 THE FOLLOWING PARTS OF THIS THESIS HAVE BEEN REDACTED FOR COPYRIGHT REASONS: p15, Fig 1.1 p214, Fig 8.8 p16, Fig 1.2 p216, Fig 8.9 p17, Fig -

Societies Forum Agenda

Societies Forum Agenda Ø Activities Officer Update Ø Societies Committee Update Ø Branding Ø Any Other Business @durhamSU /durhamSU www.durhamsu.com Activities Officer Update Ø Re-registration Ø Grants Updates Ø Student Group Training @durhamSUact [email protected] @durhamSU /durhamSU www.durhamsu.com Re-registration • We’re going to be tighter on re-registration this year as previously its led to issues. • The deadline for registration is 31st May. • Any societies not registered by this point will cease to be a registered society with the Students’ Union. • Any societies who do not meet this deadline with have to wait until the October Assembly meeting meaning they will not be able to attend Freshers’ Fair or apply for grant funding. @durhamSU /durhamSU www.durhamsu.com Re-registration Rationale • Having a clear deadline means that the Students’ Union will be able to decide and promote the fresher's fair activities to incoming students. • We will be holding training in June (which is a requirement for grant applications) by which by then all AGMs should have taken place. • Re-registering (and holding AGMs) in good time maximises participation in the elections and gives incoming execs longer to plan over summer. @durhamSU /durhamSU www.durhamsu.com Grants Headline figures • 66 student groups applied for funding in this round of ordinary grant allocations, totalling £39,689.20. • The majority of applicants received at least a proportion of the amount they applied for. £22,071.00 was available in funding of which £18,116.71 was granted to student groups, leaving a remainder of £3,954.29. -

Kuwaittimes 10-12-2019.Qxp Layout 1

RABIA ALTHANI 13, 1441 AH TUESDAY, DECEMBER 10, 2019 28 Pages Max 20º Min 07º 150 Fils Established 1961 ISSUE NO: 18006 The First Daily in the Arabian Gulf www.kuwaittimes.net Finland picks world’s youngest Miss South Africa wins Gender-segregated entrances Russia banned from Olympics 6 PM to head women-led cabinet 19 Miss Universe crown 24 for eateries scrapped in Saudi 28 and World Cup over doping Fitch: Kuwait political disputes to delay debt issuance, reform Ratings agency forecasts budget deficit of over 5% of GDP as oil prices fall HONG KONG/LONDON: The Kuwaiti government’s resignation and subsequent cabinet reshuffle point to No more survivors on NZ political frictions that could delay new debt issuance and weigh on broader fiscal and economic reforms, Fitch Ratings said in a report issued yesterday. Kuwait has island after volcano eruption been the slowest reformer in the Gulf Cooperation Council in recent years, partly due to these frictions and WELLINGTON: New Zealand police try and find those trapped “no signs of partly due to its exceptionally large sovereign assets, have said no more survivors were life have been seen at any point”. which could finance decades’ worth of fiscal deficits. expected to be rescued from an island “Based on the information we have, we “Parliamentary authorization to issue or refinance volcano that erupted suddenly yester- do not believe there are any survivors debt expired in 2017 and governments have been unable day, suggesting as many as two dozen on the island. Police is working urgently to secure approval for renewed borrowing. -

CONTENTS Towards a General Theory of Jewish Political Interests and Behaviour � Peter Y

VOLUME xix: NUMBER 2 DECEMBER 1977 CONTENTS Towards a General Theory of Jewish Political Interests and Behaviour Peter Y. Medding The Socially Disadvantaged Peer Group in the Israeli Resi- dential Setting Mordecai Arieli and Yitzhak Kashti The Conquest of a Community? The Zionists and the Board of Deputies in 1917 Stuart A. Cohen The Secular Jew: Does He Exist and Why? (Review Article) - Israel Finestein Jewish Gold and Prussian Iron (Review Article) Lloyd P. Gartner Editor: Maurice Freedman Managing Editor: Jvdith Freedman The Jewish Journal of Sociology NOTICE TO SUBSCRIBERS BACK NUMBERS Most of the issues of The Jewish Journal of Sociology for the years 1959, 1961, 1962, 1963, 1964, 1965. and 1966 are out of print Many of the libraries and institutions of higher learning that subscribe to our Journal are extremely anxious to obtain copies of these out-of-print issues. The editors of the J.J.S. are therefore appealing to subscribers who may be willing to dispose of these issues to write to the Managing Editor at 55 New Cavendish Street, London Wi M 813T. indicating which numbers they have for sale. If the issues are in good condition the J.J.S. will be glad to buy them back at a fair price and to reimburse postage expenses. Alternatively. the J.J.S. would be willing to exchange a future issue of the Journal against one of the out-of-print issues. THE JEWISH JOURNAL OF SOCIOLOGY VOLUME XIX NO. 2 DECEMBER 1977 CONTENTS Towards a General Theory of Jewish Political Interests and Behaviour Peter Y. -

Talksport Sanction Decision

Sanction (124)19 Talksport Limited Decision by Ofcom Sanction: to be imposed on Talksport Limited For material broadcast on Talk Radio on 16 March, 27 July and 6 August 20181 Ofcom’s Decision of Sanction against: Talksport Ltd (“Talksport” or the “Licensee”) in respect of its service Talk Radio (DN000015BA/5) For: Breaches of the Ofcom Broadcasting Code (the “Code”)2 in respect of: Rule 5.11: “…due impartiality must be preserved on matters of major political and industrial controversy and major matters relating to current public policy by the person providing a service…in each programme or in clearly linked and timely programmes”; and Rule 5.12: “In dealing with matters of major political and industrial controversy and major matters relating to current public policy an appropriately wide range of significant views must be included and given due weight in each programme or in clearly linked and timely programmes. Views and facts must not be misrepresented”. Decision: To impose a financial penalty (payable to HM Paymaster General) of £75,000; and To direct the Licensee to broadcast a statement of Ofcom’s findings in a form and on date(s) to be determined by Ofcom. 1 See Broadcast and On Demand Bulletins 371 and 375 for the material broadcast on Talk Radio and found in breach of Ofcom’s Broadcasting Code (“the Code”), (https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0025/134755/Issue-371-of-Ofcoms-Broadcast-and-On- Demand-Bulletin.pdf, https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0024/142098/Issue-375-Ofcoms- Broadcast-and-On-Demand-Bulletin.pdf) 2 The version of the Code which was in force at the time of the broadcast took effect on 3 April 2017: (https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/100103/broadcast-code-april-2017.pdf) 1 Sanction (124)19 Talksport Limited Executive Summary 1.