Status and Occurrence of Flesh-Footed Shearwater (Ardenna Carneipes) in British Columbia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wedge-Tailed Shearwater Ardenna Pacifica Fallout Patterns Inform Targeted Management

Friswold et al.: Targeted management of Wedge-tailed Shearwater 245 WEDGE-TAILED SHEARWATER ARDENNA PACIFICA FALLOUT PATTERNS INFORM TARGETED MANAGEMENT BROOKE FRISWOLD1*, KEITH SWINDLE2, DAVID HYRENBACH3 & MELISSA R. PRICE1 1Department of Natural Resources & Environmental Management, University of Hawai‘i at Mˉanoa, 1910 East-West Rd., Honolulu, HI 96822, USA ([email protected]) 2United States Fish and Wildlife Service, 3375 Koapaka St., Honolulu, HI 96819, USA 3Hawai‘i Pacific University, 45-045 Kamehameha Hwy, Kˉane‘ohe, HI 96744, USA Received 17 January 2020, accepted 03 July 2020 ABSTRACT FRISWOLD, B., SWINDLE, K., HYRENBACH, D. & PRICE, M.R. 2020. Wedge-tailed Shearwater Ardenna pacifica fallout patterns inform targeted management. Marine Ornithology 48: 245–254. Seabird fledglings are often attracted to artificial, bright lights, leading to their grounding. This phenomenon is termed “fallout” and is associated with an increased risk of mortality from land-based threats. This study evaluated temporal trends and spatial factors, such as fallout clustering near lights and proximity to colonies, to inform targeted management actions. Standardized surveys were conducted from 2002 to 2010 for Wedge-tailed Shearwater Ardenna pacifica (WTSH) fallout on the island of O‘ahu, Hawai‘i, USA. First, yearly fallout counts along the transect showed a two-year cycle and identified 25 November as the date with the highest fallout across years. Second, artificial lights and utility lines were present in 94% and 83% of fallout locations, leading to significantly higher fallout rates at these locations compared to random points along the transect. Third, fallout decreased significantly as the distance from the colonies increased and was negligible farther than 5 km from the nearest colony. -

Behavior and Attendance Patterns of the Fork-Tailed Storm-Petrel

BEHAVIOR AND ATTENDANCE PATTERNS OF THE FORK-TAILED STORM-PETREL THEODORE R. SIMONS Wildlife Science Group, Collegeof Forest Resources, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington 98195 USA ABSTRACT.--Behavior and attendance patterns of breeding Fork-tailed Storm-Petrels (Ocea- nodromafurcata) were monitored over two nesting seasonson the Barren Islands, Alaska. The asynchrony of egg laying and hatching shown by these birds apparently reflects the influence of severalfactors, including snow conditionson the breedinggrounds, egg neglectduring incubation, and food availability. Communication between breeding birds was characterized by auditory and tactile signals.Two distinct vocalizationswere identified, one of which appearsto be a sex-specific call given by males during pair formation. Generally, both adults were present in the burrow on the night of egg laying, and the male took the first incubation shift. Incubation shiftsranged from 1 to 5 days, with 2- and 3-day shifts being the most common. Growth parameters of the chicks, reproductive success, and breeding chronology varied considerably between years; this pre- sumably relates to a difference in conditions affecting the availability of food. Adults apparently responded to changes in food availability during incubation by altering their attendance patterns. When conditionswere good, incubation shifts were shorter, egg neglectwas reduced, and chicks were brooded longer and were fed more frequently. Adults assistedthe chick in emerging from the shell. Chicks became active late in the nestling stage and began to venture from the burrow severaldays prior to fledging. Adults continuedto visit the chick during that time but may have reducedthe amountof fooddelivered. Chicks exhibiteda distinctprefledging weight loss.Received 18 September1979, accepted26 July 1980. -

Full Text in Pdf Format

Vol. 651: 163–181, 2020 MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Published October 1 https://doi.org/10.3354/meps13439 Mar Ecol Prog Ser OPEN ACCESS Habitat preferences, foraging behaviour and bycatch risk among breeding sooty shearwaters Ardenna grisea in the Southwest Atlantic Anne-Sophie Bonnet-Lebrun1,2,3,8,*, Paulo Catry1, Tyler J. Clark4,9, Letizia Campioni1, Amanda Kuepfer5,6,7, Megan Tierny6, Elizabeth Kilbride4, Ewan D. Wakefield4 1MARE − Marine and Environmental Sciences Centre, ISPA - Instituto Universitário, Rua Jardim do Tabaco 34, 1149-041 Lisboa, Portugal 2Department of Zoology, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB2 3EJ, UK 3Centre d’Ecologie Fonctionnelle et Evolutive CEFE UMR 5175, CNRS — Université de Montpellier - Université Paul-Valéry Montpellier — EPHE, 34293 Montpellier cedex 5, France 4Institute of Biodiversity, Animal Health and Comparative Medicine, University of Glasgow, Glasgow G12 8QQ, UK 5FIFD — Falkland Islands Fisheries Department, Falkland Islands Government, PO Box 598, Stanley, Falkland Islands, FIQQ 1ZZ, UK 6SAERI — South Atlantic Environmental Research Institute, Stanley, Falkland Islands, FIQQ 1ZZ, UK 7Environment and Sustainability Institute, University of Exeter, Penryn Campus, Penryn TR10 9FE, UK 8Present address: British Antarctic Survey, High Cross, Madingley Road, Cambridge CB4 0ET, UK 9Present address: Wildlife Biology Program, Department of Ecosystem and Conservation Sciences, W.A. Franke College of Forestry and Conservation, University of Montana, 32 Campus Drive, Missoula, Montana 59812, USA ABSTRACT: Pelagic seabirds are important components of many marine ecosystems. The most abundant species are medium/small sized petrels (<1100 g), yet the sub-mesoscale (<10 km) distri- bution, habitat use and foraging behaviour of this group are not well understood. Sooty shearwaters Ardenna grisea are among the world’s most numerous pelagic seabirds. -

Sooty Shearwater Puffinus Griseus Few Changes in Bird Distribution

110 Petrels and Shearwaters — Family Procellariidae Sooty Shearwater Puffinus griseus birds are picked up regularly on the county’s beaches. Few changes in bird distribution have been as sud- Winter: From December to March the Sooty Shearwater den and dramatic as the Sooty Shearwater’s deser- is rare—currently much scarcer than the Short-tailed tion of the ocean off southern California. Before the Shearwater. Before 1982, winter counts ranged up to 20 1980s, this visitor from the southern hemisphere off San Diego 18 January 1969 (AFN 23:519, 1969). Since was the most abundant seabird on the ocean off San 1987, the highest winter count has been of three between San Diego and Los Coronados Islands 6 January 1995 (G. Diego in summer. After El Niño hit in 1982–83 and McCaskie). the ocean remained at an elevated temperature for the next 20 years, the shearwater’s numbers dropped Conservation: The decline of the Sooty Shearwater by 90% (Veit et al. 1996). A comparison confined followed quickly on the heels of the decline in ocean to the ocean near San Diego County’s coast would productivity off southern California that began in the likely show a decline even steeper. late 1970s: a decrease in zooplankton of 80% from 1951 to 1993 (Roemich and McGowan 1995, McGowan et al. Migration: The Sooty Shearwater begins arriving in April, 1998). The shearwater’s declines were especially steep in peaks in May (Briggs et al. 1987), remains (or remained) years of El Niño, and from 1990 on there was no recov- common through September, and then decreases in ery even when the oceanographic pendulum swung the number through December. -

First Record, and Recovery of Wedge-Tailed Shearwater Ardenna Pacifica from the Andaman Islands, India S

RAJESHKUMAR ET AL.: Wedge-tailed Shearwater 113 First record, and recovery of Wedge-tailed Shearwater Ardenna pacifica from the Andaman Islands, India S. Rajeshkumar, C. Raghunathan & N. P. Abdul Aziz Rajeshkumar, S., Raghunathan, C., & Aziz, N. P. A., 2015. First record, and recovery of Wedge-tailed Shearwater Ardenna pacifica from the Andaman Islands, India. Indian BIRDS. 10 (5): 113–114. S. Rajeshkumar, Zoological Survey of India, Andaman and Nicobar Regional Centre, Port Blair 744102, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, India. E-mail: [email protected] [Corresponding author.] C. Raghunathan, Zoological Survey of India, Andaman and Nicobar Regional Centre, Port Blair 744102, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, India. E-mail: [email protected] N. P. Abdul Aziz, Department of Environment and Forests, Andaman and Nicobar Administration, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, India. E-mail: [email protected] Manuscript received on 25 May 2015. edge-tailed Shearwaters Ardenna pacifica are widely Indonesia (Poole et al. 2011). distributed, and breed throughout the tropical Pacific-, We report here the recovery of a live Wedge-tailed Shearwater Wand Indian Oceans (BirdLife International 2015). Two [93] on the Andaman Islands, in May 2015; that it later died in races are recognised: A. p. pacifica breeds in the south-eastern captivity. This is the first specimen recorded for India. Remarkably, part of the northern Pacific Ocean, andA. p. chlororhyncha breeds all the previously documented records from India were also from in the tropical, and sub-tropical Indian-, and Pacific- Oceans (del May. It could be assumed that this species is a spring passage Hoyo et al. 2014). Large breeding colonies of the species exist migrant across the Arabian Sea, the Bay of Bengal, and in the on oceanic islands between latitudes 35°N and 35°S, such as Indian Ocean. -

FEEDING ECOLOGY of the CAPE VERDEAN SHEARWATER (Calonectris Edwardsii) POPULATION of RASO ISLET, CAPE VERDE (P1-B-11)

2nd World Seabird Conference “Seabirds: Global Ocean Sentinels” 26-30 October 2015 Cape Town, South Africa FEEDING ECOLOGY OF THE CAPE VERDEAN SHEARWATER (Calonectris edwardsii) POPULATION OF RASO ISLET, CAPE VERDE (P1-B-11) Isabel Rodrigues1,3; Nuno Oliveira 2 Rui Freitas 3 Tommy Melo1 Pedro Geraldes 2 1Biosfera I, Cabo Verde, www.biosfera1.com; 2SPEA, Portugal, www.spea.pt, 3 Universidade de Cabo Verde, www.unicv.edu.cv Raso Islet with only 5.76 km2, is an area of great importance to Cape Verdean Shearwaters as we find one of the largest colonies of the species there. The great biological value of this islet is even more remarkable for hosting very large populations of other species, such as the Brown Booby, Red-billed Tropicalbird and even the endemic Raso Lark, among others. Along with Branco Islet, also included in the Nature Reserve, both populations constitute about 75% of the nesting population of the Cape Verde islands (Fig. 1). The Cape Verde Shearwater (Procellariiformes, Procellariidae) (Fig. 2) is an endemic species of Cape Verde and has recently been separated from Calonectris diomedea species, due to their morphological and genetic differences, and pelagic habits; feeding mostly on the open sea (Hazevoet 1995). METHODOLOGY RESULTS The samples were collected between 14 October and 12 November, in two In total, 80 regurgitations from juvenile Cape Verde Shearwaters were collected; consecutive years, 2012 and 2013. We randomly obtained 80 samples of juvenile including 50 individuals sampled in 2012, and 30 individuals in 2013. regurgitation. Each juvenile was sampled only once. During or after handling, Based on knowledge of local fish populations and according to the current juveniles tend to regurgitate stomach contents without the need to resort to the description, the identified prey of Cape Verde shearwaters belonged to 5 species induced regurgitation method. -

WEDGE-TAILED SHEARWATER Ardenna Pacifica

WEDGE-TAILED SHEARWATER Ardenna pacifica Other: ‘Ua’u kani monotypic breeding visitor, indigenous Wedge-tailed Shearwaters are found abundantly throughout the tropical Pacific and Indian oceans (Harrison 1983, AOU 1998, Wiles 2005, Whittow 1997) and are the most ubiquitous Procellariiform in the Hawaiian Islands. They breed commonly on almost every island in the archipelago and on many small offshore islets, adults arriving at the colonies in Mar, departing primarily during Sep-Nov, and remaining away from colonies and being scarce in Hawaiian waters for a short time in Jan-Feb (Richardson and Fisher 1950, King 1974, Byrd et al. 1983, Whittow 1997); young fledge primarily in Nov and are found in Hawaiian waters through Dec. Populations in the N Pacific, including Hawaii and Wake Atoll (Rauzon et al. 2008), are primarily of the light morph, with whitish underparts. Those in the equatorial and S Pacific, generally south of 10° N latitude, are primarily of the dark morph, with uniform sooty brown underparts and upperparts. Low proportions (< 3%) of dark-morph and intermediate-morph birds are found in Hawaiian waters (e.g., King 1974; HRBP 5624, 5799-5800), in particular at-sea S and W of Hawai'i I during mid-summer (cf. Force and Ballance 2009), but rarely among breeding colonies in Hawaii (cf. Stejneger 1889, Rothschild 1900). Leucistic individuals (e.g., HRBP 1334-1337) are occasionally encountered, and an unidentified albino shearwater photographed off Hawai'i I in May 1990 (HRBP 0924-0927) was most likely a Wedge-tailed. Wedge-tailed Shearwater was placed in genus Puffinus (pacificus) until moved to Ardenna (pacifica) by the AOU (2016). -

Status and Occurrence of Manx Shearwater (Puffinus Puffinus) in British Columbia

Status and Occurrence of Manx Shearwater (Puffinus puffinus) in British Columbia. By Rick Toochin and Louis Haviland. Introduction and Distribution The Manx Shearwater (Puffinus puffinus) is a small species of shearwater found year round along both sides of the North Atlantic Ocean (Onley and Scofield 2007). This species has breeding colonies in Iceland, France, Faeroe Island, Ireland, Scotland, England, Channel Islands, Azores Islands, Madeira Island, and the Canary Islands (Onley and Scofield 2007). In eastern North America, the Manx Shearwater breeds in Newfoundland and is found in the Gulf of St. Lawrence to the Gulf of Maine (Lee and Haney 1996). Some of these birds winter in the North Atlantic Ocean off North America from the Carolinas to Florida, but most birds are trans- equatorial migrants from July to March wintering in the South Atlantic Ocean off Brazil to Argentina and spread across the South Atlantic to South Africa (Lee and Haney 1996, Onley and Scofield 2007). The Manx Shearwater has been undergoing a somewhat mysterious range expansion over the past few decades with more and more birds turning up in the North Pacific Ocean (Roberson 1996, Mlodinow 2004). Though breeding is suspected it has yet to be proven (Mlodinow 2004). One bird was tape recorded at night in a nesting burrow on Triangle Island by Dr. Ian Jones in the summer of 1994 (Mlodinow 2004). The bird was never actually seen and the bird’s identity was left unidentified for many years (P. Jones Pers. Comm.). Another possible breeding record comes from Alaska on Middleton Island on May 12, 2005, when 2 birds were seen together possibly prospecting for a nest site (Gibson et al. -

The Depth of Sooty Shearwater Ardenna Grisea Burrows Varies With

Ibis (2019), 161, 192–197 doi: 10.1111/ibi.12631 Short communication than other substrates, indicating how vegetation restora- tion could aid the conservation of this species. The depth of Sooty Keywords: burrow dimensions, burrowing petrels, Falkland Islands, nest architecture, Puffinus griseus. Shearwater Ardenna grisea burrows varies with Many seabirds, including most small-medium Procellari- habitat and increases with iformes (hereafter ‘petrels’), as well as many alcids and some penguins, breed in burrows. Yet, burrows are ener- competition for space getically costly to build and can be subject to flooding, † TYLER J. CLARK,1, * ANNE-SOPHIE collapse and other disadvantages (Warham 1996). BONNET-LEBRUN,2,3 LETIZIA CAMPIONI,4 Therefore, the advantages of protection from predators PAULO CATRY4 & EWAN WAKEFIELD1 and climatic extremes must outweigh the costs of bur- 1Institute of Biodiversity, Animal Health, and row nesting. Burrow nesting by seabirds can have wider Comparative Medicine, University of Glasgow, Graham effects, such as modifying the structure and nutrient Kerr Building, Glasgow G12 8QQ, UK content of island soils, which can then cascade to other 2Department of Zoology, University of Cambridge, trophic levels (Bancroft et al. 2005). In other fossorial Downing Street, Cambridge CB2 3EJ, UK animals, the impact of these processes depends in part 3Centre d’Ecologie Fonctionnelle et Evolutive CEFE on the structure of the burrow systems (Laundre & Rey- UMR 5175, CNRS - Universite de Montpellier - nolds 1993). Some petrels, such as the White-chinned Universite Paul-Valery Montpellier – EPHE, 919 route Petrel Procellaria aequinoctialis or the Flesh-footed de Mende 34293, Montpellier Cedex 5, France Shearwater Ardenna carneipes construct relatively simple 4MARE – Marine and Environmental Sciences Centre, and straight burrows (Parker & Rexer-Huber 2015). -

The Foraging Ecology of the Short-Tailed Shearwater (Ardenna Tenuirostris): Life-History Strategies and Climate Change

The foraging ecology of the short-tailed shearwater (Ardenna tenuirostris): Life-history strategies and climate change Natalie Bool BSc (Australian National University), BSc (Hons) (University of Adelaide) Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Tasmania April 2018 Declaration of originality This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis, nor does the thesis contain any material that infringes copyright. Natalie Bool 27 April 2018 i Authority of access This thesis may be made available for loan. Copying and communication of any part of this thesis is prohibited for two years from the date this statement was signed; after that time limited copying and communication is permitted in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. Natalie Bool 27 April 2018 ii Statement of ethical conduct The research associated with this thesis abides by the international and Australian codes on human and animal experimentation, the guidelines by the Australian Government's Office of the Gene Technology Regulator and the rulings of the Safety, Ethics and Institutional Biosafety Committees of the University. All animal handling and instrumentation was carried-out under Research Permits, Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment (FA05151, FA10212, FA13009, FA14063, FA15083, FA16077) and University of Tasmania Ethics Committee permits (A8138, A11338, A128942, A15572). -

Newell's Shearwater

Seabirds ‘A‘o or Newell’s Shearwater Puffinus auricularis newelli SPECIES STATUS: Federally listed as Threatened State listed as Threatened State recognized as Indigenous Photo: Brenda Zaun, USFWS NaturServe Heritage Rank G2/T2 – Imperiled species/Imperiled subspecies North American Waterbird Conservation Plan - Highly imperiled IUCN Red List Ranking - Endangered Regional Seabird Conservation Plan - USFWS 2005 SPECIES INFORMATION: The ‘a‘o or Newell’s shearwater (Family: Procellaridae) is highly pelagic year-round, and is endemic to the Hawaiian Islands at the subspecific level. Adult males and females are dark, sooty brown above, with white throat and underparts, and have a dark bill with a hooked tip. Flight is direct, fast and usually low over water, powered by rapid wing beats interspersed with glides; wing loading is higher than in more aerial shearwaters due to the species’ foraging method (see below). Often forages in large, mixed species flocks associated with schools of large, predatory fishes which drive prey species to the surface. ‘A‘o (Newell’s shearwater) feed mainly by pursuit-plunging; individuals dive into water and swim using their partly folded wings for propulsion. Diet is not well known, but likely consists of fish and squid. ‘A‘o (Newell’s shearwater) are colonial and nest on steep mountain slopes, with variable amounts of vegetation, where they lay a single egg in burrows, which are often placed at the base of a tree. Breeding is highly synchronous, and eggs are laid in early June, and most young fledge by November. Both parents incubate egg, and brood and feed nestling. Parents forage hundreds of kilometers offshore and return to colony at night to feed chick. -

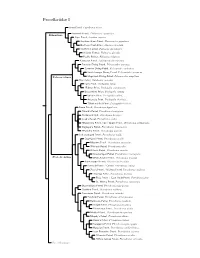

Procellariidae Species Tree

Procellariidae I Snow Petrel, Pagodroma nivea Antarctic Petrel, Thalassoica antarctica Fulmarinae Cape Petrel, Daption capense Southern Giant-Petrel, Macronectes giganteus Northern Giant-Petrel, Macronectes halli Southern Fulmar, Fulmarus glacialoides Atlantic Fulmar, Fulmarus glacialis Pacific Fulmar, Fulmarus rodgersii Kerguelen Petrel, Aphrodroma brevirostris Peruvian Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides garnotii Common Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides urinatrix South Georgia Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides georgicus Pelecanoidinae Magellanic Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides magellani Blue Petrel, Halobaena caerulea Fairy Prion, Pachyptila turtur ?Fulmar Prion, Pachyptila crassirostris Broad-billed Prion, Pachyptila vittata Salvin’s Prion, Pachyptila salvini Antarctic Prion, Pachyptila desolata ?Slender-billed Prion, Pachyptila belcheri Bonin Petrel, Pterodroma hypoleuca ?Gould’s Petrel, Pterodroma leucoptera ?Collared Petrel, Pterodroma brevipes Cook’s Petrel, Pterodroma cookii ?Masatierra Petrel / De Filippi’s Petrel, Pterodroma defilippiana Stejneger’s Petrel, Pterodroma longirostris ?Pycroft’s Petrel, Pterodroma pycrofti Soft-plumaged Petrel, Pterodroma mollis Gray-faced Petrel, Pterodroma gouldi Magenta Petrel, Pterodroma magentae ?Phoenix Petrel, Pterodroma alba Atlantic Petrel, Pterodroma incerta Great-winged Petrel, Pterodroma macroptera Pterodrominae White-headed Petrel, Pterodroma lessonii Black-capped Petrel, Pterodroma hasitata Bermuda Petrel / Cahow, Pterodroma cahow Zino’s Petrel / Madeira Petrel, Pterodroma madeira Desertas Petrel, Pterodroma