NBA Expansion and Relocation: a Viability Study of Various Cities Daniel A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Valuation of NFL Franchises

Valuation of NFL Franchises Author: Sam Hill Advisor: Connel Fullenkamp Acknowledgement: Samuel Veraldi Honors thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Graduation with Distinction in Economics in Trinity College of Duke University Duke University Durham, North Carolina April 2010 1 Abstract This thesis will focus on the valuation of American professional sports teams, specifically teams in the National Football League (NFL). Its first goal is to analyze the growth rates in the prices paid for NFL teams throughout the history of the league. Second, it will analyze the determinants of franchise value, as represented by transactions involving NFL teams, using a simple ordinary-least-squares regression. It also creates a substantial data set that can provide a basis for future research. 2 Introduction This thesis will focus on the valuation of American professional sports teams, specifically teams in the National Football League (NFL). The finances of the NFL are unparalleled in all of professional sports. According to popular annual rankings published by Forbes Magazine (http://www.Forbes.com/2009/01/13/nfl-cowboys-yankees-biz-media- cx_tvr_0113values.html), NFL teams account for six of the world’s ten most valuable sports franchises, and the NFL is the only league in the world with an average team enterprise value of over $1 billion. In 2008, the combined revenue of the league’s 32 teams was approximately $7.6 billion, the majority of which came from the league’s television deals. Its other primary revenue sources include ticket sales, merchandise sales, and corporate sponsorships. The NFL is also known as the most popular professional sports league in the United States, and it has been at the forefront of innovation in the business of sports. -

To Authorize the Merger of Two Or More Professional

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CU Scholar Institutional Repository University of Colorado, Boulder CU Scholar Undergraduate Honors Theses Honors Program Spring 2016 “To Authorize the Merger of Two or More Professional Basketball Leagues:” Professional Basketball’s 1971-72 Congressional Hearings and the Fight for Player Freedoms Samuel R. Routhier [email protected], [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.colorado.edu/honr_theses Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Routhier, Samuel R., "“To Authorize the Merger of Two or More Professional Basketball Leagues:” Professional Basketball’s 1971-72 Congressional Hearings and the Fight for Player Freedoms" (2016). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 1177. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Honors Program at CU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of CU Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “To Authorize the Merger of Two or More Professional Basketball Leagues:” Professional Basketball’s 1971-72 Congressional Hearings and the Fight for Player Freedoms Samuel Routhier A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of the Arts in History with honors University of Colorado, Boulder Defended April 5, 2016 Committee: Dr. Thomas Zeiler, Thesis Advisor, International Affairs Dr. Mithi Mukherjee, History Dr. Patrick Ferrucci, Journalism Abstract This thesis examines the congressional hearings in 1971 and 1972 regarding American professional basketball’s request for an exemption from antitrust law. Starting in 1970, the players of the National Basketball Association fought in court and Congress to change the league’s business practices, in particular the reserve system. -

“A Functional Well-Appointed Locker Room

A FUNCTIONAL, WELL APPOINTED LOCKER ROOM In a huge sports complex like the Target Center, located in downtown Min- neapolis, Minnesota, the locker room may be considered almost an after- thought. Yet in order to attract and keep a National Basketball Association team and to provide a highly visible location for pre- and post-game televi- sion interviews, the locker room becomes much more important. The Target Center is a city owned sports and entertainment facility constructed in 1989 as a requirement to receive a National Basketball Association team. The NBA Minnesota Timberwolves remain a primary user of the facility. To replace the plain laminate locker room, the Minneapolis Community Devel- opment Agency (MCDA) went to architect Setter, Leach & Lindstrom of Min- neapolis. The architects decided to design a facility that would be a functional locker room yet give the apearance of a well appointed boardroom. Their Photos by H. Larson Photography goal was to provide a quality locker room environment for an NBA team, and the room had to be a presentable space for functions such as televised player A view of the locker room showing the interviews. They selected cherry for the lockers, cabinetry, paneling and trim hardware installed inside the lockers. Like the cherry woodwork, the hardware because of its color and quality appearance. AWI member Siewert Cabinet was selected for durability in a high wear & Fixture Mfg., Inc. of Minneapolis provided the high quality woodwork area as well as appearance. Selecting and throughout the room. installing the hardware presented a challenge to the woodworker The locker room is a hard use area, so the lockers had to be durable and carefully designed to wear well. -

Wildcats in the Nba

WILDCATS IN THE NBA ADEBAYO, Bam – Miami Heat (2018-20) 03), Dallas Mavericks (2004), Atlanta KANTER, Enes - Utah Jazz (2012-15), ANDERSON, Derek – Cleveland Cavaliers Hawks (2005-06), Detroit Pistons Oklahoma City Thunder (2015-17), (1998-99), Los Angeles Clippers (2006) New York Knicks (2018-19), Portland (2000), San Antonio Spurs (2001), DIALLO, Hamidou – Oklahoma City Trail Blazers (2019), Boston Celtics Portland Trail Blazers (2002-05), Thunder (2019-20) (2020) Houston Rockets (2006), Miami Heat FEIGENBAUM, George – Baltimore KIDD-GILCHRIST, Michael - Charlotte (2006), Charlotte Bobcats (2007-08) Bulletts (1950), Milwaukee Hawks Hornets (2013-20), Dallas Mavericks AZUBUIKE, Kelenna -- Golden State (1953) (2020) Warriors (2007-10), New York Knicks FITCH, Gerald – Miami Heat (2006) KNIGHT, Brandon - Detroit Pistons (2011), Dallas Mavericks (2012) FLYNN, Mike – Indiana Pacers (1976-78) (2012-13), Milwaukee Bucks BARKER, Cliff – Indianapolis Olympians [ABA in 1976] (2014-15), Phoenix Suns (2015-18), (1950-52) FOX, De’Aaron – Sacramento Kings Houston Rockets (2019), Cleveland BEARD, Ralph – Indianapolis Olympians (2018-20) Cavaliers (2010-20), Detroit Pistons (1950-51) GABRIEL, Wenyen – Sacramento Kings (2020) BENNETT, Winston – Clevland Cavaliers (2019-20), Portland Trail Blazers KNOX, Kevin – New York Knicks (2019- (1990-92), Miami Heat (1992) (2020) 20) BIRD, Jerry – New York Knicks (1959) GILGEOUS-ALEXANDER, Shai – Los KRON, Tommy – St. Louis Hawks (1967), BLEDSOE, Eric – Los Angeles Clippers Angeles Clippers (2019), Oklahoma Seattle -

Coaching Staff 2008-09 MEAC Champs ● 2009 MEAC Tournament Champs ● Mid-Major Coach of the Year

Coaching Staff 2008-09 MEAC Champs ● 2009 MEAC Tournament Champs ● Mid-Major Coach of the Year 2009-10 Morgan State Bears Basketball • 1 5 Head Coach Todd Bozeman 2008-09 MEAC Champs ● 2009 MEAC Tournament Champs ● Mid-Major Coach of the Year ranked No. 23 in the Mid-Major 7 in the Washington Post Atlantic Top 25, No. 6 in the Washington 11 poll. Post Atlantic 11 Poll, and No. 1 in After a 7-8 start, the Bears reeled the Sheridan Broadcasting Network off an incredible eight straight (SBN) Black College Poll. victories, equaling its longest The Bears tallied eight wins at winning streak since 1975, and Hill Field House and made its first closed out the regular season by NCAA Tournament appearance in winning 13 of their last 14 regular school history as a No. 15 seed. season games. The Bears were led by the MEAC’s The team also proved it could top ranked point guard Jermaine compete against some of the nation’s “Itchy” Bolden, who wrapped the best teams, as it suffered four-point Bears’ historic season with a school losses at UConn and Miami, and record 170 assists. Marquise Kately were outlasted by Seton Hall by and Reggie Holmes also played 8-points earlier during the season. pivotal roles in the Bears success Morgan State men’s basketball and they were named to the All- coach Todd Bozeman was selected MEAC team and selected to the the 2008 Mid-Eastern Athletic In just three seasons at the helm, National Association of Basketball Conference Coach of the Year. -

Other Basketball Leagues

OTHER BASKETBALL LEAGUES {Appendix 2.1, to Sports Facility Reports, Volume 13} Research completed as of August 1, 2012 AMERICAN BASKETBALL ASSOCIATION (ABA) LEAGUE UPDATE: For the 2011-12 season, the following teams are no longer members of the ABA: Atlanta Experience, Chi-Town Bulldogs, Columbus Riverballers, East Kentucky Energy, Eastonville Aces, Flint Fire, Hartland Heat, Indiana Diesels, Lake Michigan Admirals, Lansing Law, Louisiana United, Midwest Flames Peoria, Mobile Bat Hurricanes, Norfolk Sharks, North Texas Fresh, Northwestern Indiana Magical Stars, Nova Wonders, Orlando Kings, Panama City Dream, Rochester Razorsharks, Savannah Storm, St. Louis Pioneers, Syracuse Shockwave. Team: ABA-Canada Revolution Principal Owner: LTD Sports Inc. Team Website Arena: Home games will be hosted throughout Ontario, Canada. Team: Aberdeen Attack Principal Owner: Marcus Robinson, Hub City Sports LLC Team Website: N/A Arena: TBA © Copyright 2012, National Sports Law Institute of Marquette University Law School Page 1 Team: Alaska 49ers Principal Owner: Robert Harris Team Website Arena: Begich Middle School UPDATE: Due to the success of the Alaska Quake in the 2011-12 season, the ABA announced plans to add another team in Alaska. The Alaska 49ers will be added to the ABA as an expansion team for the 2012-13 season. The 49ers will compete in the Pacific Northwest Division. Team: Alaska Quake Principal Owner: Shana Harris and Carol Taylor Team Website Arena: Begich Middle School Team: Albany Shockwave Principal Owner: Christopher Pike Team Website Arena: Albany Civic Center Facility Website UPDATE: The Albany Shockwave will be added to the ABA as an expansion team for the 2012- 13 season. -

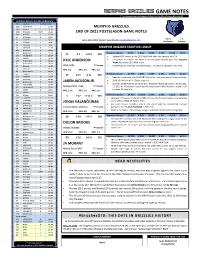

GAME NOTES for In-Game Notes and Updates, Follow Grizzlies PR on Twitter @Grizzliespr

GAME NOTES For in-game notes and updates, follow Grizzlies PR on Twitter @GrizzliesPR GRIZZLIES 2020-21 SCHEDULE/RESULTS Date Opponent Tip-Off/TV • Result 12/23 SAN ANTONIO L 119-131 MEMPHIS GRIZZLIES 12/26 ATLANTA L 112-122 12/28 @ Brooklyn W (OT) 116-111 END OF 2021 POSTSEASON GAME NOTES 12/30 @ Boston L 107-126 1/1 @ Charlotte W 108-93 38-34 1-4 1/3 LA LAKERS L 94-108 Game Notes/Stats Contact: Ross Wooden [email protected] Reg Season Playoffs 1/5 LA LAKERS L 92-94 1/7 CLEVELAND L 90-94 1/8 BROOKLYN W 115-110 MEMPHIS GRIZZLIES STARTING LINEUP 1/11 @ Cleveland W 101-91 1/13 @ Minnesota W 118-107 SF # 1 6-8 ¼ 230 Previous Game 4 PTS 2 REB 5 AST 2 STL 0 BLK 24:11 1/16 PHILADELPHIA W 106-104 Selected 30th overall in the 2015 NBA Draft after two seasons at UCLA. 1/18 PHOENIX W 108-104 First player to compile 10+ steals in any two-game playoff span since Dwyane 1/30 @ San Antonio W 129-112 KYLE ANDERSON 2/1 @ San Antonio W 133-102 Wade during the 2013 NBA Finals. th 2/2 @ Indiana L 116-134 UCLA / USA 7 Season Career-high 94 3PM this season (previous: 24 3PM in 67 games in 2019-20). 2/4 HOUSTON L 103-115 PPG: 8.4 RPG: 5.0 APG: 3.2 2/6 @ New Orleans L 109-118 2/8 TORONTO L 113-128 PF # 13 6-11 242 Previous Game 21 PTS 6 REB 1 AST 1 STL 0 BLK 26:01 2/10 CHARLOTTE W 130-114 Selected fourth overall in 2018 NBA Draft after freshman year at Michigan State. -

LACROSSE CURLING >>> CRICKET >>> >>>

FEATURE STORY YAY TEAM! Canada’s favourite sports go back a long way CURLING >>> In 1759, Scottish soldiers melted some cannonballs to make curling “stones” for a match in Quebec City. Formed in 1807, the Montreal Curling Club was the first of its kind outside Scotland. More than 710,000 Canadians curl every year, which might just make it our country’s most popular organized sport. Curling teams in >>> Winnipeg in 1906 CRICKET The first Canadian cricket clubs formed in Toronto in 1827 and St. John’s in 1828 after British soldiers brought it with them. Canada Canada, Archives Library and Commons, Flickr beat the U.S. in 1844 in the world’s first CP Images Canada, Archives Library and international cricket match. In 1867, Sir John A. Macdonald declared cricket Canada’s first national sport. 1869 Canadian lacrosse champions from the Mohawk community of Kahnawake, Que. LACROSSE >>> Canada’s official summer sport comes from a common First Nations game known by the Anishinaabe as bagaa’atowe, and as tewaarathon by the Kanien’kehá:ka. (French priests named it lacrosse in the 1630s.) Games were often used to train warriors, and could involve hundreds of players on a field as long as a kilometre. Non- Indigenous people picked up on the fast, exciting sport in the mid-1800s. William Beers, a Montreal Star Canadian cricketer dentist, wrote down rules for the first time in Amarbir Singh “Jimmy” Hansra September, 1860. 66 KAYAK DEC 2017 GURINDER OSAN, Wiki Commons,Kayak_62.indd 6 2017-11-15 10:02 AM SOCCER >>> More commonly called football in its early life, soccer was considered unladylike from the first days of organized play in the 1870s until well into the 1950s. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. IDgher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & HoweU Information Compaiy 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 OUTSIDE THE LINES: THE AFRICAN AMERICAN STRUGGLE TO PARTICIPATE IN PROFESSIONAL FOOTBALL, 1904-1962 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State U niversity By Charles Kenyatta Ross, B.A., M.A. -

923466Magazine1final

www.globalvillagefestival.ca Global Village Festival 2015 Publisher: Silk Road Publishing Founder: Steve Moghadam General Manager: Elly Achack Production Manager: Bahareh Nouri Team: Mike Mahmoudian, Sheri Chahidi, Parviz Achak, Eva Okati, Alexander Fairlie Jennifer Berry, Tony Berry Phone: 416-500-0007 Email: offi[email protected] Web: www.GlobalVillageFestival.ca Front Cover Photo Credit: © Kone | Dreamstime.com - Toronto Skyline At Night Photo Contents 08 Greater Toronto Area 49 Recreation in Toronto 78 Toronto sports 11 History of Toronto 51 Transportation in Toronto 88 List of sports teams in Toronto 16 Municipal government of Toronto 56 Public transportation in Toronto 90 List of museums in Toronto 19 Geography of Toronto 58 Economy of Toronto 92 Hotels in Toronto 22 History of neighbourhoods in Toronto 61 Toronto Purchase 94 List of neighbourhoods in Toronto 26 Demographics of Toronto 62 Public services in Toronto 97 List of Toronto parks 31 Architecture of Toronto 63 Lake Ontario 99 List of shopping malls in Toronto 36 Culture in Toronto 67 York, Upper Canada 42 Tourism in Toronto 71 Sister cities of Toronto 45 Education in Toronto 73 Annual events in Toronto 48 Health in Toronto 74 Media in Toronto 3 www.globalvillagefestival.ca The Hon. Yonah Martin SENATE SÉNAT L’hon Yonah Martin CANADA August 2015 The Senate of Canada Le Sénat du Canada Ottawa, Ontario Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0A4 K1A 0A4 August 8, 2015 Greetings from the Honourable Yonah Martin Greetings from Senator Victor Oh On behalf of the Senate of Canada, sincere greetings to all of the organizers and participants of the I am pleased to extend my warmest greetings to everyone attending the 2015 North York 2015 North York Festival. -

There's a New Sheriff in Town: Commissioner-Elect Adam Silver & the Pressing Legal Challenges Facing the NBA Through the Prism of Contraction

Volume 21 Issue 1 Article 4 4-1-2014 There's a New Sheriff in Town: Commissioner-Elect Adam Silver & the Pressing Legal Challenges Facing the NBA Through the Prism of Contraction Adam G. Yoffie Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons Recommended Citation Adam G. Yoffie, There's a New Sheriff in Town: Commissioner-Elect Adam Silver & the Pressing Legal Challenges Facing the NBA Through the Prism of Contraction, 21 Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports L.J. 59 (2014). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj/vol21/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports Law Journal by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. 34639-vls_21-1 Sheet No. 38 Side A 03/14/2014 13:49:04 \\jciprod01\productn\V\VLS\21-1\VLS104.txt unknown Seq: 1 11-MAR-14 10:46 Yoffie: There's a New Sheriff in Town: Commissioner-Elect Adam Silver & t THERE’S A NEW SHERIFF IN TOWN: COMMISSIONER-ELECT ADAM SILVER & THE PRESSING LEGAL CHALLENGES FACING THE NBA THROUGH THE PRISM OF CONTRACTION ADAM G. YOFFIE* “I have big shoes to fill.”1 – NBA Commissioner-Elect Adam Silver I. INTRODUCTION Following thirty years as the commissioner of the National Bas- ketball Association (NBA), David Stern will retire on February 1, 2014.2 The longest-tenured commissioner in professional sports, Stern has methodically prepared for the upcoming transition by en- suring that Adam Silver, his Deputy Commissioner, will succeed him.3 Following Stern’s October 2012 announcement, the NBA Board of Governors (“Board”) unanimously agreed to begin negoti- ating with Stern’s handpicked successor.4 By May 2013, Silver had signed his contract and officially had become NBA Commissioner- Elect.5 The fifth individual to hold the position, Silver faces a wide * J.D., Yale Law School, 2011; B.A., Duke University, 2006. -

This Is Cowboy Basketball

This is Cowboy Basketball " What it means to me to put on a Cowboy uniform and play in the Arena-Auditorium is kind of indescribable. To play at the only Division I university in the entire state, and not only that but to play at the same place both of my parents played, is amazing. I get goose bumps just walking into the Arena-Auditorium for practice, not even a game. I can't tell you how great I feel about putting on the Brown and Gold and having the opportunity to be a Cowboy. It is truly amazing and I thank God everyday that I get to be a part of something bigger than me."” Adam Waddell, Cody, Wyo. Sophomore Center The 1943 NCAA Champion Wyoming Cowboys. WINNING TRADITION owboy Basketball tradition is a rich one, including an NCAA National Championship team, a former coach who is WINNING a member of the Basketball Hall of Fame, an All-American who is credited with one of the greatest innovations in C the history of the game and one of the most memorable players in NCAA history. In 1943, the University of Wyoming was led to the NCAA Championship by legendary coach Everett Shelton. Shelton’s 1943 Cowboy squad defeated Georgetown in the NCAA Championship game in Madison Square Garden. Two nights later, also in Madison Square Garden, the Cowboys earned the right to call themselves undisputed National Champions as they defeated that year’s NIT Champion, St. John’s University, in a game benefi tting the Red Cross. In 1982, Coach Shelton’s memory was immortalized with the highest honor in basketball — induction into the Basketball Hall of Fame in Springfi eld, Mass.