Project Outline and the Actual Proceedings of the Regional Brain Gain Project Are Presented in the Following Sections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

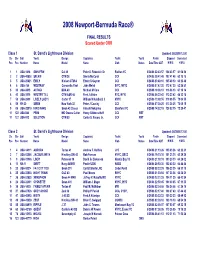

ORR Results Printout

2008 Newport-Bermuda Race® FINAL RESULTS Scored Under ORR Class 1 St. David's Lighthouse Division Updated: 06/28/08 12:00 Cls Div Sail Yacht Design Captain(s) Yacht Yacht Finish Elapsed Corrected Pos Pos Number Name Model Name Club Status Date/Time ADT H M S H M S 1 1 USA-1818 SINN FEIN Cal 40 Peter S. Rebovich Sr. Raritan YC 6/24/08 22:43:57 104 43 57 61 06 38 2 2 USA-40808 SELKIE CTM 38 Sheila McCurdy CCA 6/24/08 20:41:48 102 41 48 62 10 18 3 5 USA-20621 EMILY Nielsen CTM 44 Edwin S Gaynor CCA 6/24/08 23:48:10 105 48 10 63 23 48 4 6 USA-754 WESTRAY Concordia Yawl John Melvin IHYC, NYYC 6/25/08 07:47:20 113 47 20 63 25 51 5 30 USA-3815 ACTAEA BDA 40 Michael M Cone CCA 6/25/08 10:36:13 116 36 13 67 18 14 6 43 USA-3519 WESTER TILL CTM A&R 48 Fred J Atkins EYC, NYYC 6/25/08 06:22:42 112 22 42 68 32 18 7 58 USA-2600 LIVELY LADY II Carter 37 William N Hubbard, III NYYC 6/25/08 13:08:55 119 08 55 70 04 55 8 59 NY-20 SIREN New York 32 Peter J Cassidy CCA 6/25/08 07:38:25 113 38 25 70 05 15 9 86 USA-32510 HIRO MARU Swan 43 Classic Hiroshi Nakajima Stamford YC 6/25/08 14:02:15 120 02 15 73 25 47 11 122 USA-844 PRIM MO Owens Cutter Henry Gibbons-Neff CCA RET 11 122 USA-913 SOLUTION CTM 50 Carter S. -

Rolex Swan Cup

Galeria de fotos Rolex Swan Cup imagens Ref: 1_swan18cb_21780 Ref: 2_swan18cb_15852 Ref: 3_swan18cb_17442 Ref: 4_swan18cb_07697 OWNERS OF THE SIX CLASS ONEGROUP, WINNER OF THE PLIS-PLAY, WINNER OF THE MAXI SPANISH ENTRY PORRON IX, WINNERS AT THE 2018 ROLEX INAUGURAL CLUBSWAN50 WORLD CLASS AT THE 2018 ROLEX SWAN WINNER OF THE SWAN 45 WORLD SWAN CUP RECEIVE THEIR CHAMPIONSHIP CUP CHAMPIONSHIP TROPHIES FROM GIAN RICCARDO MARINI OF ROLEX ITALY AND Créditos: © Rolex/ Carlo Borlenghi Créditos: © Rolex/ Carlo Borlenghi Créditos: © Rolex/ Carlo Borlenghi LEONARDO FERRAGAMO, CHAIRMAN OF NAUTOR'S SWAN Créditos: © Rolex/ Carlo Borlenghi Ref: 5_swan18cb_12954 Ref: 6_swan18cb_13412 Ref: 7_swan18cb_14703 Ref: 8_swan18cb_16281 SIX JAGUAR, WINNER OF THE SOLTE, WINNER OF THE GRAND MELA, WINNER OF THE 2016 WORLD CHAMPION ELENA SPARKMAN & STEPHENS CLASS PRIX CLASS AT THE 2018 ROLEX CLUBSWAN 42 EUROPEAN NOVA AND DEFENDING CHAMPION AT THE 2018 ROLEX SWAN CUP SWAN CUP CHAMPIONSHIP AT THE 2018 PORRON IX CONTEST THE SWAN ROLEX SWAN CUP 45 WORLD TITLE Créditos: © Rolex/ Carlo Borlenghi Créditos: © Rolex/ Carlo Borlenghi Créditos: © Rolex/ Carlo Borlenghi Créditos: © Rolex/ Carlo Borlenghi 1 / 6 Galeria de fotos Rolex Swan Cup Ref: 9_swan18cb_14926 Ref: 10_swan18cb_15315 Ref: 11_swan18cb_16193 Ref: 12_swan18cb_16587 THE ROLEX SWAN CUP FLEET FULL FOCUS ONBOARD STELLA SELENE, A SWAN 80, AND THE THE 2018 ROLEX SWAN CUP TAKE ON THE LONG ISLAND MARIS, CUORDILEONE AND 100-FT VARSOVIE, IN THE SWAN ATTRACTED A DIVERSE FLEET OF COASTAL RACE EARLYBIRD IN THE CLUBSWAN 50 -

ARC2004 Results by Div-Class

ARC 2004 Provisional Results Motoring Penalty 1.2 Time difference UTC -4 hours Finish time local EngElapsed Corrected Position Nr Yacht Name Type Nat. TCF Date h:m:s hrs dd/ h:m:s dd/h:m:s Div Cl Division I - Cruising Class A 35 Voodoo Oyster 66 AUS 1.122 06-Dec 02:13:04 48.25 14/ 17:13:04 18/18:26:49 16 1 25 Serenite Ron Holland 76 ITA 1.236 05-Dec 10:34:04 45 14/ 01:34:04 19/16:51:14 37 2 59 Perseverance Swan 56 USA 1.149 07-Dec 01:13:00 37.7 15/ 16:13:00 19/19:35:25 40 3 33 Goodwinds Oyster 66 GBR 1.122 06-Dec 04:08:30 78.5 14/ 19:08:30 20/06:32:45 58 4 58 Mediterraneo Starkel 64 ITA 1.187 06-Dec 23:08:25 39.83 15/ 14:08:25 20/11:23:12 67 5 37 Amoenitas Andre Hoek 68 GER 1.140 09-Dec 08:21:23 12.75 17/ 23:21:23 21/02:16:53 82 6 43 Albatros Swan 62RS GER 1.135 08-Dec 10:48:50 40 17/ 01:48:50 21/06:32:20 89 7 36 Desirade III Nauta 65 ITA 1.230 07-Dec 05:05:00 48.83 15/ 20:05:00 21/23:34:03 110 8 34 Sundowner Oyster 66 USA 1.122 06-Dec 02:57:29 117.15 14/ 17:57:29 22/00:34:60 113 9 56 Satika Beneteau 57 SUI 1.125 09-Dec 00:58:35 49.08 17/ 15:58:35 22/04:11:32 114 10 67 Ursula Taswell 56 ESP 1.129 08-Dec 22:21:20 58.4 17/ 13:21:20 22/13:38:38 118 11 53 La Royere II Beneteau 57 FRA 1.125 08-Dec 10:09:50 86 17/ 01:09:50 23/05:03:34 126 12 98 Lady Dynamite Bavaria 49 GER 1.121 10-Dec 13:16:20 47.67 19/ 04:16:20 23/17:23:58 131 13 55 Nae Hassle Beneteau 57 GBR 1.125 09-Dec 12:07:05 74.8 18/ 03:07:05 23/21:39:28 132 14 30 Altair Oyster 68 GBR 1.125 08-Dec 10:43:36 112.07 17/ 01:43:36 24/11:01:03 133 15 97 Inspiration Bavaria 49 GBR 1.121 09-Dec -

Berthon Central Listings - Sailing from 50Ft LOA

Berthon Central Listings - Sailing From 50ft LOA Model: Kestrel 106' KESTREL Ron Holland good looks, a Tardis above and below decks and powerful sailing performance. Once in code, this Kestrel 106' would be an epic charter yacht too. Spain Builder: Aganlar Tersanesi, Turkey 106 (ft) 2012 Price: GBP 1250000 Excl. VAT Model: Comet 100 RS SHADOW Epic sailing yacht with metallic livery and totally sparkling sailing. Below decks she is light, airy and comfortable for her guests and crew. Genoa, Italy Builder: Comar 101.9 (ft) 2011 Price: € 4250000 Excl. VAT Model: CNB 93 SAVARONA Great looking sailing yacht which is available fresh from a nautical makeover of epic proportions including decks, paint, interior and all systems. Gleaming. Palma de Mallorca Builder: Navale, Bordeaux 93.4 (ft) 2001 Price: USD 2750000 Model: Frers 92 BRISTOLIAN Iconic and very special Frers 92 cruiser / racer that is well known on the international regatta circuit with her blue black livery and classic Frers lines. She continues to win hearts and minds wherever she goes, and comes with new cloth and other performance updates. She is priced to sell. Palma de Mallorca Builder: CNB 92.5 (ft) 1989 Price: GBP 800000 Model: Dubois 92' Ketch LICORNE Astonishing Dubois design, totally fettled for very serious planet circuiting, she likes the cold places and has form there. Now ready for her next foray. Marmaris, Turkey Builder: Dubbel & Jesse 92 (ft) 1985 Price: GBP 850000 08 December 2016 Page 1 of 16 Berthon Central Listings - Sailing From 50ft LOA Model: Jongert 27m ISABEL Good looking ketch from the Jongert stable that has been cherished through life - truckloads of splosh have been expended in her ownerships which is why she looks this good today. -

Customer Comments About Berthon TAONUI, 42Ft Sailing Yacht That Looks Like a Very Thorough and Effective Piece of Work and Just What I Wanted

Home | About Berthon | Lymington Marina | New Boat Sales | Brokerage Sales | Yacht Maintenance | Onan Generators | Weather & Tide Customer Comments About Berthon TAONUI, 42ft Sailing Yacht That looks like a very thorough and effective piece of work and just what I wanted. Please tell them well done from me... and thanks. Introduction eNews Newsletter DAWN LIGHT, Windy 28 ...thanks for the clean up, she looked fabulous when we arrived at the weekend. Customer Comments Recruitment RADIANT, Southerley 110 I think that the fault that you found must have cured the problem. With thanks for your most efficient help in this. History Build Register ELSIE D, Westerley 33 Many thanks for organising the renovation of our gas system. It is a relief to have it all sorted out. Location Contact Us DUCK DHU, Moody 46 Please pass on my thanks to all involved for not only an excellent job, but done in record time. Or is this the norm for Berthon? If so, great - it's the best on the Solent. BLUE SKIES, Dragon Just a short note to thank you for all your help yesterday. I can't tell you what a difference it makes to deal with people who are both totally professional and happy to help in whatever way they can. OTTERS WAY OF BEAULIEU, Linssen 470 AC Mk II Thanks for all your support and help. JUPITER, Linssen 299 AC Thank you for all the advice, training and fantastic handover to us of Jupiter. PURITAN, Giles 38 Just a few lines to thank you and your engineer, David, for getting us away on Friday. -

Classe Irc A-Pavillon Violet

VOILES DE SAINT TROPEZ 2011- CLASSE IRC A-PAVILLON VIOLET NOM COULEUR CLASSE JAUGE N° VOILE AN TYPE NOM RESULTAT 1 AIYANA VIOLET IRCA 1.348 CAY 821 2010 CRUISING SLOOP PETER CORR 2 ALPINA BY FINIMMO VIOLET IRCA 1.388 BVI OO7 2001 SWAN 80 BENOIT DE FROIDMONT 3 ANNAGINE VIOLET IRCA 1.423 NED 26 2011 ANNAGINE CHARTER LTD 4 ARAGON VIOLET IRCA 1.473 NED 27 2006 MARTEN 72 ARAGON 5 AROBAS VIOLET IRCA 1.338 FRA 60101 2004 SWAN601 GERARD LOGEL 6 BLUE DIAMOND VIOLET IRCA 1.496 FRA 9517 2004 PROTOTYPE 7 CARBON ARROW VIOLET IRCA 1.466 FRA 5535 2004 MARTEN 72 PHILIPPE MEYER 8 CHRISCO VIOLET IRCA 1.523 MLT 1000 2008 CNB 100 9 CUORDISOLE VIOLET IRCA 1.343 NED 8046 2005 SWAN 601 10 DISCO INFERNO 3 VIOLET IRCA 1.195 GBR 6021L 2007 BORDEAUX 60 MATT ABBISS 11 DRUMFIRE VIOLET IRCA 1.208 GER 6446 2004 TRULLY CLASSIC 78 TIM VAN DER WEIDE 12 FELICIE VIOLET IRCA 1.138 FRA 6345 1974 PRESLE 65 13 FINSCO VIOLET IRCA 1.195 GER 4560 1995 MR 19.20 14 FIREFLY VIOLET IRCA 1.533 F /01 2011 115FT RACE CLASSIC "FIREFLY" ERIC BYLSMA 15 GAIA VIOLET IRCA 1.430 36 2007 MODERN CLASSIC SLOOP SJIK 16 GERONIMO VIOLET IRCA 1.200 NED 7183 1989 SWAN 651 ERIK VELDHUIZEN 17 GITANA 6 VIOLET IRCA 1.140 6387 1975 PROTOTYPE GITANA TEAM 18 HIGHLAND BREEZE VIOLET IRCA 1.364 NED 888 2002 SWAN 112 RS ALBERT KEULARTS 19 HIGHLANDFLING VIOLET IRCA 1.655 MON 888 2009 PROTOTYPE IRVIN LAIDLAW 20 IVANKA VIOLET IRCA 1.403 CAY 2011 2010 SHIPMAN 80 IVANKA 21 JETHOU VIOLET IRCA 1.472 GBR 74R 2009 JUDEL / VROLIJK 60 SIR PETER OGDEN 22 LEOPARD 3 VIOLET IRCA 1.818 GBR 1R 2008 FARR M. -

Rolex Swan Cup

Formulario de contacto Rolex Swan Cup imágenes Ref.: 1_swan18cb_21780 Ref.: 2_swan18cb_15852 Ref.: 3_swan18cb_17442 Ref.: 4_swan18cb_07697 OWNERS OF THE SIX CLASS ONEGROUP, WINNER OF THE PLIS-PLAY, WINNER OF THE MAXI SPANISH ENTRY PORRON IX, WINNERS AT THE 2018 ROLEX INAUGURAL CLUBSWAN50 WORLD CLASS AT THE 2018 ROLEX SWAN WINNER OF THE SWAN 45 WORLD SWAN CUP RECEIVE THEIR CHAMPIONSHIP CUP CHAMPIONSHIP TROPHIES FROM GIAN RICCARDO MARINI OF ROLEX ITALY AND Créditos de foto: © Rolex/ Carlo Créditos de foto: © Rolex/ Carlo Créditos de foto: © Rolex/ Carlo LEONARDO FERRAGAMO, Borlenghi Borlenghi Borlenghi CHAIRMAN OF NAUTOR'S SWAN Créditos de foto: © Rolex/ Carlo Borlenghi Ref.: 5_swan18cb_12954 Ref.: 6_swan18cb_13412 Ref.: 7_swan18cb_14703 Ref.: 8_swan18cb_16281 SIX JAGUAR, WINNER OF THE SOLTE, WINNER OF THE GRAND MELA, WINNER OF THE 2016 WORLD CHAMPION ELENA SPARKMAN & STEPHENS CLASS PRIX CLASS AT THE 2018 ROLEX CLUBSWAN 42 EUROPEAN NOVA AND DEFENDING CHAMPION AT THE 2018 ROLEX SWAN CUP SWAN CUP CHAMPIONSHIP AT THE 2018 PORRON IX CONTEST THE SWAN ROLEX SWAN CUP 45 WORLD TITLE Créditos de foto: © Rolex/ Carlo Créditos de foto: © Rolex/ Carlo Borlenghi Borlenghi Créditos de foto: © Rolex/ Carlo Créditos de foto: © Rolex/ Carlo Borlenghi Borlenghi 1 / 6 Formulario de contacto Rolex Swan Cup Ref.: 9_swan18cb_14926 Ref.: 10_swan18cb_15315 Ref.: 11_swan18cb_16193 Ref.: 12_swan18cb_16587 THE ROLEX SWAN CUP FLEET FULL FOCUS ONBOARD STELLA SELENE, A SWAN 80, AND THE THE 2018 ROLEX SWAN CUP TAKE ON THE LONG ISLAND MARIS, CUORDILEONE AND 100-FT VARSOVIE, -

Ocean Globe Race 2023-24 NOTICE of RACE Sept. 10Th 2022 PATRON

Ocean Globe Race 2023-24 NOTICE OF RACE Sept. 10th 2022 PATRON: Sir Charles Blyth CBE BEM. “ In the Spirit of the original 1973 Whitbread Race” Celebrating its 50th Anniversary. The Organiser reserves the right to amend this NOTICE OF RACE 2023-24. The text in English language is to be taken as definitive in the event of any jurisdiction or dispute of whatever nature. Copyright- Ocean Frontiers Pty Ltd. © 2019-2024. All rights reserved. V3 www.OceanGlobeRace.com 1 DEFINITIONS 6 1.1 Ocean Globe Race 6 1.2 Organiser 6 1.3 Website of the OGR 6 1.4 Patron & Host 6 1.5 NOTICE OF RACE 6 1.6 Boats 6 1.7 OGR Director 6 1.8 Timetables 6 1.9 Official Sponsors of the Ocean Globe Race 7 1.10 Participant 7 1.10.1 A Skipper 7 1.10.2 A Chief Mate. 7 1.10.3 Sponsors 7 1.10.4 Team Manager 7 1.10.5 Crew 7 1.10.6 Audio-visual referral agent 8 1.11 OGR Headquarters 8 1.12 Executive Producer 8 1.13 Questions by a Skipper or a Team Manager after registration. 8 1.14 Routing 8 1.15 Medical service of the OGR 8 1.16 Skipper 8 1.17 Official Notice Board 8 1.18 Contributors 9 1.19 Abbreviations 9 2 THE RACE 9 2.1 Entry and Registration 9 2.2 Dates 10 1st August 2022 10 1st April 2023 10 1st JULY 2023 10 10th July 2023 11 2.3 Number of participants and OGR Number 11 2.3.1 The number of entries 11 2.3.2 OGR Number 11 2.3.3 Special Inclusion 11 2.3.4 Two Special Invitations and the Waitlist 11 2.3.5 No more than seven Entries from one country. -

1/4 Tonner 0,896 Odd Job GBR3341 Cowes Week 2006 1/4 Tonner 0,897 Espada Wanchai Belle GBR50R Cowes Week 2006 1/4 Tonner 0,902 C

1/4 Tonner 0,896 Odd Job GBR3341 Cowes Week 2006 1/4 Tonner 0,897 Espada Wanchai Belle GBR50R Cowes Week 2006 1/4 Tonner 0,902 Catch GBR502 Cowes Week 2006 1D 35 1,132 Hell Hound 35038 http://www.ussailing.org/offshore/IRC/IRC_TCCs_2006.ASP 1D 35 1,132 Yankee 35042 http://www.ussailing.org/offshore/IRC/IRC_TCCs_2006.ASP 1D 35 1,134 Sensational http://www.navwiz.com/subdreamer/index.php?categoryid=276 1D 35 1,140 Tabasco 35047 http://www.ussailing.org/offshore/IRC/IRC_TCCs_2006.ASP 3/4 tonner IOR 0,960 Impeccable MH106 http://rolexsydneyhobart.com 31' Norwalk Island Sharpie 0,992 Serano http://www.navwiz.com/subdreamer/index.php?categoryid=116 37 Holiday 0,974 Darwin Star http://www.navwiz.com/subdreamer/index.php?categoryid=92 8 Metre 0,969 Yucca 8526 http://www.ussailing.org/offshore/IRC/IRC_TCCs_2006.ASP 8 Metre 1,001 If GBR27 Cowes Week 2006 8M Cr/Racer 0,921 Marian Maid http://www.navwiz.com/subdreamer/index.php?categoryid=24 A 35 1,026 Batistyl FRA27912 http://rorc.org/comcup/media/teams.php A 35 1,026 Passe Partout FRA390 http://rorc.org/raceresults06/msovos.html A 40 1,097 Banque Populaire - Kunkel Palettes FRA29222 http://rorc.org/raceresults06/msovos.html A 40 1,122 Stamina II FRA21660 http://rorc.org/raceresults06/msovos.html Abeking & Rasmussen 0,905 Westray 754 http://www.ussailing.org/offshore/IRC/IRC_TCCs_2006.ASP Abeking & Rasmussen 0,968 Wester Till 3519 http://www.ussailing.org/offshore/IRC/IRC_TCCs_2006.ASP Adams 10 0,967 Great Scot Ii http://www.navwiz.com/subdreamer/index.php?categoryid=82 Adams 10 0,970 Top Gun R363 -

ARC 2011 Ratings

ARC 2011 - Provisional List of Ratings 16/11/2011 TCF BoatName ID Boat Design LOA Owner NAT Cruising 1.175 Meltemi 89 Beneteau Oceanis 54 16.70 DHH Yachtschule Elba GER 1.175 Adelante (FIN) 90 one off 16.70 Kari Lattu FIN 1.170 Argonaut 91 Berckemeyer 54 16.50 Frits Draijer NED 1.146 GUNVØR XL 77 X-55 16.76 Karsten Christian Witt GER 1.146 go 250 Pogo 1050 10.50 Sven Thurau GER 1.125 Twelve Moons 94 Hanse 545 16.20 Stefan Schollmayer GER 1.116 Ko-Ko 63 Najad 570 17.50 Haakon Dyremyhr NOR 1.115 Lone Star 67 Amel 54 17.20 Craig Scott USA 1.114 Dreamer 57 Oyster 575 17.89 Chris Glossop GBR 1.114 Sophistikate 58 Oyster 575 17.89 Richard Parkinson GBR 1.110 Hunny Pot 123 Beneteau First 50 14.99 Andrew Wicklow GBR 1.108 Adrienne 104 Gibsea 51 15.80 Segelschule Hofbauer AUT 1.107 Brizo (USA) 115 Beneteau 50 15.10 Lewis Wallner USA 1.107 Elphin II 139 Beneteau Oceanis 50 15.10 Stuart Reed GBR 1.099 Sulyna 64 Tayana 58 17.46 Andrew Allan GBR 1.095 Buzios VII 125 Jeanneau Sun Odyssey 49P 14.98 Jose Matos Almeida POR 1.091 Ma Vie 117 Jeanneau Sun Odyssey 50DS 15.07 Thomas Savera GER 1.091 Kinnirossi Blue 118 Jeanneau Sun Odyssey 50DS 15.07 Paul Devereux GBR 1.090 Pura Vida 6 161 Hanse 470e 14.31 Antonio Sotilla ESP 1.084 Pied-à-Mer 106 Elan Impression 514 16.10 Walid Halabi FRA 1.083 Nandina 103 Dufour Gibsea 51 15.80 Juan Queirolo PER 1.077 Persevere 59 Beneteau 57 17.80 Bruce Jones USA 1.076 Working on a Dream 124 Jeanneau Sun Odyssey 49 14.96 Hans Hansell SWE 1.076 Kotari 130 Jeanneau Sun Odyssey 49 14.96 Chris Clark GBR 1.072 Casamara 72 Discovery -

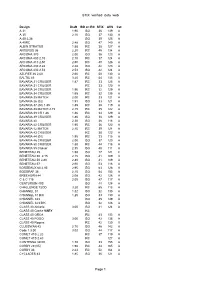

STIX Verified Data Web Page 1

STIX_verified_data_web Design Draft ISO or IRC STIX AVS Cat A 31 1.90 ISO 36 139 A A 35 2.10 ISO 37 130 A A 40 2.38 ISO 39 125 A A 40RC 2.48 ISO 47 140 A ALBIN STRATUS 1.88 IRC 38 127 A ANTEROS 36 2.20 IRC 45 134 A ARCONA 370 2.00 ISO 36 123 A ARCONA 400 2.10 2.10 IRC 37 124 A ARCONA 410 2.50 2.50 IRC 40 126 A ARCONA 430 2.28 2.28 ISO 42 123 A ARCONA 430 2.53 2.53 ISO 42 124 A AZUREE 46 2.60 2.60 IRC 50 130 A BALTIC 45 3.25 IRC 54 135 A BAVARIA 31 CRUISER 1.87 IRC 33 125 A BAVARIA 31 CRUISER IRC 33 120 A BAVARIA 34 CRUISER 1.90 IRC 32 129 A BAVARIA 34 CRUISER 1.55 IRC 32 135 A BAVARIA 35 MATCH 2.00 IRC 33 121 A BAVARIA 36 (02) 1.91 ISO 33 121 A BAVARIA 37 (00) 1.85 1.85 IRC 38 119 A BAVARIA 38 MATCH 2.15 2.15 IRC 35 122 A BAVARIA 39 CR 1.86 1.86 IRC 34 129 A BAVARIA 39 CRUISER 1.86 ISO 34 129 A BAVARIA 40 2.30 ISO 36 118 A BAVARIA 42 CRUISER 1.95 IRC 36 122 A BAVARIA 42 MATCH 2.45 IRC 39 124 A BAVARIA 43 CRUISER IRC 38 122 A BAVARIA 44 (01) 1.95 IRC 33 115 A BAVARIA 46 CRUISER 2.00 ISO 37 120 A BAVARIA 50 CRUISER 1.80 IRC 44 116 A BAVARIA 55 Cruiser 2.35 ISO 49 111 A BENETEAU 25 1.58 ISO 17 121 C BENETEAU 50 2.15 2.15 ISO 41 109 A BENETEAU 50 2.80 2.80 ISO 41 109 A BENETEAU 57 2.60 ISO 53 116 A BORDEAUX 60 2.95 2.95 ISO 63 126 A BOSGRAF 36 2.10 ISO 54 153 A BREEHORN 44 2.08 ISO 42 126 A C & C 115 2.05 ISO 47 117 A CENTURION 40S ISO 44 128 A CHALLENGE 72OD 3.20 IRC 65 118 A CHANNEL 31 1.82 ISO 32 130 A CHANNEL 31 B/K 1.25 ISO 33 130 A CHANNEL 323 ISO 35 149 A CHANNEL 323 B/K ISO 32 146 A CLASS 40 Akilaria 3.00 ISO 41 124 A CLASS 40 Clarke -

UNITED STATES PERFORMANCE HANDICAP RACING FLEET LOW, HIGH, AVERAGE and MEDIAN PERFORMANCE HANDICAPS for the Years 2005 Through 2011 IMPORTANT NOTE

UNITED STATES PERFORMANCE HANDICAP RACING FLEET LOW, HIGH, AVERAGE AND MEDIAN PERFORMANCE HANDICAPS for the years 2005 through 2011 IMPORTANT NOTE The following pages lists base performance handicaps (BHCPs) and low, high, average, and median performance handicaps reported by US PHRF Fleets for well over 4100 boat classes or types displayed in Adobe Acrobat portable document file format. Use Adobe Acrobat’s ‘FIND” feature, <CTRL-F>, to display specific information in this list for each class. Class names conform to US PHRF designations. The information for this list was culled from data sources used to prepare the “History of US PHRF Affiliated Fleet Handicaps for 2011”. This reference book, published annually by the UNITED STATES SAILING ASSOCIATION, is often referred to as the “Red, White, & Blue book of PHRF Handicaps”. The publication lists base handicaps in seconds per mile by Class, number of actively handicapped boats by Fleet, date of last reported entry and other useful information collected over the years from more than 60 reporting PHRF Fleets throughout North America. The reference is divided into three sections, Introduction, Monohull Base Handicaps, and Multihull Base Handicaps. Assumptions underlying determination of PHRF Base Handicaps are explicitly listed in the Introduction section. The reference is available on-line to US SAILING member PHRF fleets and the US SAILING general membership. A current membership ID and password are required to login and obtain access at: http://offshore.ussailing.org/PHRF/2011_PHRF_Handicaps_Book.htm . Precautions: Reported handicaps base handicaps are for production boats only. One-off custom designs are not included. A base handicap does not include fleet adjustments for variances in the sail plan and other modifications to designed hull form and rig that determine the actual handicap used to score a race.