Leif Erikson of the Sagas. Cornelia Steketee Hulst 193

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

October 1973, Vol

THE WESTON HISTORICAL SOCIETY BULLETIN October 1973, Vol. X, No. 1 1889 NORUMBEGA MEMORIAL TOWER 1973 RESTORATION (See Story on Page 2) June 20 July 9 July 30 August 14 ANNUAL MEETING JOSIAH SMITH TAVERN WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 7th 8:00 P.M. In keeping with tradition, brief reports of committees and officers will precede the recommendations of the Nominating Committee for three directors. The terms of Erlund Field, Edward W. Marshall, and Mrs. Arthur A. Nichols are expiring. Continuing for another year are Mrs. Marshall Dwinnell, Mrs. Stanley G. French, and Donald D. Douglass, and for two more years Brenton H. Dickson, 3rd, Mrs. Dudley B. Dumaine, Grant M. Palmer, Jr., and Harold G. Travis. At the conclusion of the business meeting, a program of home talent has been arranged that should be of interest to every member. The theme will be: SHEDDING NEW LIGHT ON WESTON’S PAST In preparation for the oncoming Bicentennial, a great deal of careful research has been done on Weston during the Revolutionary period. Messrs. Douglass, Gambrill, Lucas, and Travis will each touch briefly on some new facts about that era that have been un¬ covered. It is hoped that a large attendance will fill the Ball Room for this meeting. ANOTHER NOTEWORTHY RESTORATION IN WESTON Pictured on page 1 are four stages of the rebuilding of the famous Norsemen’s Tower which over¬ looks the winding Charles River off Norumbega Road in Weston. When he first took office as Metro¬ politan District Commissioner for the Commonwealth, we found Hon. John W. Sears most sympathetic to our plea for this restoration, but it took time and patience on the part of both of us while he worked out many problems of administration, priorities, and budget. -

The Extent of Indigenous-Norse Contact and Trade Prior to Columbus Donald E

Oglethorpe Journal of Undergraduate Research Volume 6 | Issue 1 Article 3 August 2016 The Extent of Indigenous-Norse Contact and Trade Prior to Columbus Donald E. Warden Oglethorpe University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/ojur Part of the Canadian History Commons, European History Commons, Indigenous Studies Commons, Medieval History Commons, Medieval Studies Commons, and the Scandinavian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Warden, Donald E. (2016) "The Extent of Indigenous-Norse Contact and Trade Prior to Columbus," Oglethorpe Journal of Undergraduate Research: Vol. 6 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/ojur/vol6/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Oglethorpe Journal of Undergraduate Research by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Extent of Indigenous-Norse Contact and Trade Prior to Columbus Cover Page Footnote I would like to thank my honors thesis committee: Dr. Michael Rulison, Dr. Kathleen Peters, and Dr. Nicholas Maher. I would also like to thank my friends and family who have supported me during my time at Oglethorpe. Moreover, I would like to thank my academic advisor, Dr. Karen Schmeichel, and the Director of the Honors Program, Dr. Sarah Terry. I could not have done any of this without you all. This article is available in Oglethorpe Journal of Undergraduate Research: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/ojur/vol6/iss1/3 Warden: Indigenous-Norse Contact and Trade Part I: Piecing Together the Puzzle Recent discoveries utilizing satellite technology from Sarah Parcak; archaeological sites from the 1960s, ancient, fantastical Sagas, and centuries of scholars thereafter each paint a picture of Norse-Indigenous contact and relations in North America prior to the Columbian Exchange. -

Read Book Leif the Lucky Ebook, Epub

LEIF THE LUCKY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Ingri D'Aulaire,Edgar Parin D'Aulaire | 60 pages | 15 Oct 2014 | University of Minnesota Press | 9780816695454 | English | Minnesota, United States Leif the Lucky PDF Book Breakwater Books. University of Minnesota Press Coming soon. Home World History Global Exploration. Edgar Parin d'Aulaire. Oct 09, Sara rated it it was amazing. Wikimedia Commons Wikisource. Retrieved 12 October There is ongoing speculation that the settlement made by Leif and his crew corresponds to the remains of a Norse settlement found in Newfoundland, Canada , called L'Anse aux Meadows and which was occupied c. Categories : Leif Erikson s births s deaths Converts to Christianity from pagan religions Explorers of Canada Icelandic explorers Icelandic sailors Norse colonization of North America Scandinavian explorers of North America Viking explorers 10th-century Icelandic people 11th-century Icelandic people. Ingri had grown up in Norway; Edgar, the son of a noted portrait painter, was born in Switzerland and had lived in Paris and Florence. The pictures are marvellous, and the story is good, though not quite as good as others by the same author. By signing up, you agree to our Privacy Notice. The Telegraph. This book tries to sidestep this power dynamic by negotiating with the dignity of the natives that Leif's brother finds by representing them as cartoonish, buffoonish people who are good for trading fur and an occasional laugh p. Lists with This Book. Cambridge University Press. But the other son quickly jumped in and said it wasn't boring, but really cool. As the years pass, food for the Vikings in Greenland becomes scarce and the lack of food and the cold causes them to become smaller in stature. -

About Leif Erikson

CK_3_TH_HG_P091_145.QXD 4/11/05 10:56 AM Page 143 French equivalent of Norsemen, meaning “men from the north.” It is another term for the Vikings. The Normans settled, intermarried with the French, and soon began to speak French. In 1066 CE, William, Duke of Normandy (also known as William the Conqueror) and his Norman forces invaded England and seized control, estab- lishing what was to become the modern country of England. William was more French than Viking. Likewise, when other Normans moved into the Mediterranean and took over Sicily at about the same time, they, too, had lost most of their Viking heritage. Teaching Idea Eric the Red and Leif Ericson Make an overhead from Instructional Master 25, Viking Voyages West, to While the Vikings from Sweden and Denmark were looking south and east, help students visualize the stepping the Vikings from Norway were moving west. From the close-in islands like the stones the Vikings used in their Hebrides, they sailed farther out to the Orkney and Faroe Islands. From there exploration west and to understand they went to Iceland and farther west still to Greenland—and then North how far Leif Ericson and his crew America. traveled in a small boat across the By 870, the Vikings had reached Iceland. In Iceland, the Vikings found a land open seas. To give students an even that was virtually unpopulated and suited for agriculture. At this time, Norwegian greater appreciation of the small size monarchs were attempting to exert their power over the country, thus antagoniz- of longships, you may wish to mark ing many chiefs and others. -

Valuing Immigrant Memories As Common Heritage

Valuing Immigrant Memories as Common Heritage The Leif Erikson Monument in Boston TORGRIM SNEVE GUTTORMSEN This article examines the history of the monument to the Viking and transatlantic seafarer Leif Erikson (ca. AD 970–1020) that was erected in 1887 on Common- wealth Avenue in Boston, Massachusetts. It analyzes how a Scandinavian-American immigrant culture has influenced America through continued celebration and commemoration of Leif Erikson and considers Leif Erikson monuments as a heritage value for the public good and as a societal resource. Discussing the link between discovery myths, narratives about refugees at sea and immigrant memo- ries, the article suggests how the Leif Erikson monument can be made relevant to present-day society. Keywords: immigrant memories; historical monuments; Leif Erikson; national and urban heritage; Boston INTRODUCTION At the unveiling ceremony of the Leif Erikson monument in Boston on October 29, 1887, the Governor of Massachusetts, Oliver Ames, is reported to have opened his address with the following words: “We are gathered here to do honor to the memory of a man of whom indeed but little is known, but whose fame is that of having being one of those pioneers in the world’s history, whose deeds have been the source of the most important results.”1 Governor Ames was paying tribute to Leif Erikson (ca. AD 970–1020) from Iceland, who, according to the Norse Sagas, was a Viking Age transatlantic seafarer and explorer.2 At the turn History & Memory, Vol. 30, No. 2 (Fall/Winter 2018) 79 DOI: 10.2979/histmemo.30.2.04 79 This content downloaded from 158.36.76.2 on Tue, 28 Aug 2018 11:30:49 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Torgrim Sneve Guttormsen of the nineteenth century, the story about Leif Erikson’s being the first European to land in America achieved popularity in the United States. -

America Not Discovered by Columbus

.7 . '^W^'. » PROFESSOR ANDERSON'S WORKS. NORSE MYTHOLOGY; ok, The Religion of Our Forefa- thers. Containing all the Myths of the Eddae, carefully sys- tematized and interpreted. With an Introduction, Vocabulary, and Index. 47-3 pages, crown 8vo; cloth, $2.50; cloth, gilt edges, $3; half calf, $5. "Prof. Anderson's work is incomparably superior to the already existing books of this order. '"—Sa^ibner's Monthly. "We have never seen so complete a view of the religion of the Norsemen."—^iS^io^^eca Sacra. "No such account of the old Scandinavian Mythology has hitherto been given in the English language. It is full, and eluci- dates the subject from all points of \iew."—Presbyterian Qtiar- terly and Princeton Review. "The exposition, analysis, and interpretation of the Norse Mythology leave nothing to be desired. The whole structure and framework of the system are here; and, in addition to this, co- pious literal translations from the Eddas and Sagas show the reader something of the literary form in which the system found permanent record. Occasionally entire songs or poems are pre- sented, and, at every point where they could be of service, illus- trative extracts accompany the elucidations of the text. " Prof. Anderson, indeed, has left little to be performed by future workers in the special field covered by his present work. * * His work is very nearly perfect."— A^j^^^eto/i's Journal. AMERICA NOT DISCOVERED BY COLUMBUS. A Historical Sketch of the Discovery of America by the Norsemen in the 10th century; with an Appendix on the Historical, Literary and Scientific value of the Scandinavian Languages. -

284818-Sample.Pdf

Sample file “Erik sailed out from Snæfellsjokul; A general timeline of he found land, and came in from the sea to the place which he called Midjokul; it is now Viking Exploration hight Blaserkr. He then went southwards to see whether it was there habitable land. The 789A.D. Norse raids on England begin first winter he was at Eriksey, nearly in the middle of the eastern settlement; the spring 794 Norse raids on Scotland begin after repaired he to Eriksfjord, and took up there his abode. 795 Norse raids on Ireland begin 844 Norse raids on Spain begin He removed in summer to the western settlement, and gave to many places names. 845 Norse raids on France pick up He was the second winter at Holm in momentum Hrafnsgnipa, but the third summer went 860 Iceland discovered he to Iceland, and came with his ship into Vikings attack Constantinople Breidafjord. He called the land which he had found Greenland, because, quoth he, 870 Iceland settlement begins in earnest “people will be attracted thither, if the land 900 Vikings raid along the Mediterranean has a good name.” Erik was in Iceland for the winter, but the summer after, went he 911 Normandy established by Rollo to colonize the land; he dwelt at Brattahlid in Eriksfjord. Informed people say that the 941 Vikings attack Constantinople again same summer Erik the Red went to colo- 981 Erik the Red discovers Greenland nize Greenland, thirty-five ships sailed from Breidafjord and Borgafjord, but only 986 Vikings explore the waters and shore- fourteen arrived; some were driven back, and line of Newfoundland others were lost.” 995 Norway officially converts to Christianity Saga of the Greenlanders 1000 Christianity is established in Greenland Leif Erikson explores the North Sample American filecoast 1010 Thorfinn Karlsefni tries to establish a settlement in North America/Vinland 1015A.D. -

2 Leif Eriksson Statue on Commonwealth Avenue, C. 1892

2 Historical Journal of Massachusetts • Summer 2021 Leif Eriksson Statue on Commonwealth Avenue, c. 1892 Eriksson stands above a dragon-headed boat which would have been the basin for a fountain. Source: Boston Public Library, Boston Pictorial Archive Collection– Mouton Photograph Company. 3 PHOTO ESSAY Vikings on the Charles: Leif Eriksson, Eben Horsford, and the Quest for Norumbega GLORIA POLIZZOTTI GREIS Editor’s Introduction: This colorful and intriguing photo essay traces how and why a statue of Norse explorer Leif Eriksson came to occupy a prominent place on Boston’s Commonwealth Avenue in 1877. A group of amateur archaeologists, scholars, and artists, all members of the Boston elite, fostered a growing interest in the theory that Leif Eriksson was the first European to reach North American shores hundreds of years before Columbus. Chemist Eben Horsford invented double-acting baking powder, a lucrative business venture which funded his obsessive interest in proving that Leif Eriksson played a much larger role in the establishment of European settlement on the continent. This photo essay follows his passionate, often misleading, and ultimately discredited contribution to the history of North America. Dr. Gloria Polizzotti Greis is the Executive Director of the Needham History Center and Museum. This is a slightly revised and expanded version of material that was first published on the museum's website.1 * * * * * Historical Journal of Massachusetts, Vol. 49 (2), Summer 2021 © Institute for Massachusetts Studies, Westfield State University 4 Historical Journal of Massachusetts • Summer 2021 At the far western end of Boston’s Commonwealth Avenue promenade, Leif Eriksson stands shading his eyes with his hand, surveying the Charlesgate flyover. -

Eben Norton Horsford, the Northmen, and the Founding of Massachusetts RICHARD R

Eben Norton Horsford, the Northmen, and the Founding of Massachusetts RICHARD R. JOHN The West is preparing to add its fables to those of the East. The valleys of the Ganges, the Nile, and the Rhine having yielded their crop, it remains to be seen what the valleys of the Amazon, the Plate, the Orinoco, the St. Lawrence, and the Mississippi will produce. Perchance, when, in the course of ages, American liberty has become a fiction of the past — as it is to some extent a fiction of the present — the poets of the world will be inspired by American mythology. —Henry David Thoreau, "Walking" On a grassy knoll overlooking the Charles River near Mount Auburn Hospital in Cambridge, Massachusetts, one can find a commemorative stone tablet with a curious inscription. Here once stood a house of Leif Erikson's, or so we are told. The inscription is so authoritative, and the tablet itself so sim- ilar to the myriad historical markers in the immediate vicinity, that it has doubtless been taken at face value by many of the Eben Norton Horsford countless passersby who have paused to make it out. After all, so many famous people have lived in Cambridge at one time 117 118 Richard R. John Eben Norton Horsford 119 or another that it would hardly seem remarkable if Leif Erik- The Erikson tablet, it turns out, was the work of neither son had, too. Yet those with at least a passing acquaintance a crank nor a fraud. Rather, it was the gift of Eben Norton with the byways of early American history are bound to find Horsford (1818-93), an industrial entrepreneur and one- this inscription more than a little odd. -

Leif Erikson Month/Day/Year Iceland My Ship Axe Throwing and Exploring University Norway in 981 A.D

Leif Erikson Month/Day/Year Iceland My ship Axe Throwing and Exploring University Norway in 981 A.D. Thorgunna Explorer Edit My Profile People you may know Sven Svensonwald 9,439 mutual Erik The Red has poked What’s on your mind? Info Boxes Yo Viking! Check out Leif Erikson this boss war axe, Just set foot upon this newfound land. I’ll call it Vinland due to the many grapes. perfect for swinging or throwing. 987 A.D. Like Comment Share Married to Thorgunna !!!Erik The Redlikes Rollo of Normandy How you gon’ top that Dora?! Info Boxes Friends (15,482) 987 A.D. Like Need to clean that Charlemagne luscious Viking beard of yours? Old Spice’ll do the job! Leif Erikson Converted to Christianity! Off to Greenland to convert the settlers Harald Hardrada 1000 A.D. Like Comment Share Erik The Redlikes Ivar The Boneless Thorfinn Karlsefni Is there even anything green in Greenland? 1001 A.D. Like Leif Erikson Month/Day/Year Iceland My ship Axe Throwing and Exploring University Norway in 981 A.D. Thorgunna Explorer Edit My Profile People you may know Pope Gregory VII 10, 453 mutual Erik The Red has poked What’s on your mind? Info Boxes Yo Viking! Check out Leif Erikson this boss war axe, My son was just born! He already has a beard perfect for swinging or throwing. 997 A.D. Like Comment Share Married to Harald Hardrada and 18,573 people like Thorgunna this. Erik The Red As a gift would he prefer an axe or spear? Info Boxes Friends (15,482) 987 A.D. -

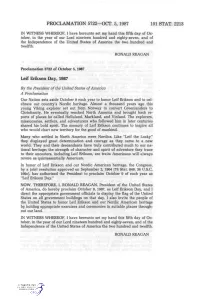

PROCLAMATION 5722—OCT. 5, 1987 101 STAT. 2213 Leif Erikson

PROCLAMATION 5722—OCT. 5, 1987 101 STAT. 2213 IN WITNESS WHEREOF, I have hereunto set my hand this fifth day of Oc tober, in the year of our Lord nineteen hundred and eighty-seven, and of the Independence of the United States of America the two hundred and twelfth. RONALD REAGAN Proclamation 5722 of October 5,1987 Leif Erikson Day, 1987 By the President of the United States of America A Proclamation Our Nation sets aside October 9 each year to honor Leif Erikson and to cel ebrate our country's Nordic heritage. Almost a thousand years ago this young Viking explorer set out from Norway to convert Greenlanders to Christianity. He eventually reached North America and brought back re ports of places he called Helluland, Markland, and Vinland. The explorers, missionaries, settlers, and adventurers who followed him in later centuries shared his bold spirit. The memory of Leif Erikson continues to inspire all who would chart new territory for the good of mankind. Many who settled in North America were Nordics. Like "Leif the Lucky" they displayed great determination and courage as they came to a new world. They and their descendants have truly contributed much to our na tional heritage; the strength of character and spirit of adventure they trace to their ancestors, including Leif Erikson, are traits Americans will always revere as quintessentially American. In honor of Leif Erikson and our Nordic American heritage, the Congress, by a joint resolution approved on September 2, 1964 (78 Stat. 849, 36 U.S.C. 169c], has authorized the President to proclaim October 9 of each year as "Leif Erikson Day." NOW, THEREFORE, I, RONALD REAGAN, President of the United States of America, do hereby proclaim October 9, 1987, as Leif Erikson Day, and I direct the appropriate government officials to display the flag of the United States on all government buildings on that day. -

Chieftain Scandinavia Freeman Monastery Norsemen Danesgold

Chieftain The leader of a village or a small group of people. Erik the Red is a figure who embodies the Vikings’ Leif Erikson is the son of Erik the Red and is The countries the Vikings came from: Norway, Scandinavia bloodthirsty reputation more completely than most. generally considered to have been the first Sweden and Denmark. Ultimately, Erik ended up founding Greenland, but European to set foot in North America, a full A person who is not a slave and free to choose Freeman that was only after he’d been banished from Iceland 500 years before Christopher Columbus. who they worked for. for murdering several men. A place where people who have dedicated their Monastery lives to religion, such as monks, live. Vikings lived in long rectangular houses with upright timber. The used woven sticks covered with The name given to people living in Scandinavia at mud to keep out the rain. Norsemen the time of the Vikings meaning ‘men of the Vikings were encouraged to wear a weapon at all times. These included spears, bow and arrow, north’. knives, swords and axes. Danesgold Money paid to Vikings to stop them from raiding. Vikings ate whatever food they could hunt, grow or make. The Vikings were skilful weavers and often made clothes for their families using natural dyes. Viking longships were used in battle and were long, light and slender so they could move around quickly. Depending on its size, a longship had 24 to 50 oars. 789 AD 840 AD 866 AD 900 AD 981 AD 1000 AD 1016 AD 1066 AD The Vikings Begin Viking Settlers Danish Vikings The Vikings raid the Eric the Red Leif Erikson (son of Erik The Danes King Harold is their attacks on establish the city establish a Kingdom Mediterranean.