Fisheries in Poland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Risk Assessment of Virus Infections in the Oder Estuary (Southern Baltic) on the Basis of Spatial Transport and Virus Decay Simulations

International Journal Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 203, 317-325 (2001) © Urban & Fischer Verlag of Hygiene and http://www.urbanfischer.de/journals/intjhyg Environmental Health Risk assessment of virus infections in the Oder estuary (southern Baltic) on the basis of spatial transport and virus decay simulations Gerald Schernewski1, Wolf-Dieter Jülich2 1 Baltic Sea Research Institute Warnemünde, Rostock-Warnemünde, Germany 2 Institute of Pharmacy, University of Greifswald, Germany Received September 13, 2000 · Accepted January 09, 2001 Abstract The large Oder (Szczecin) Lagoon (687 km2) at the German-Polish border, close to the Baltic Sea, suffers from severe eutrophication and water quality problems due to high discharge of water, nu- trients and pollutants by the river Oder. Sewage treatment around the lagoon has been very much improved during the last years, but large amounts of sewage still enter the Oder river. Human path- ogenic viruses generally can be expected in all surface waters that are affected by municipal sewage. There is an increasing awareness that predisposed persons can be infected by a few infective units or even a single active virus. Another new aspect is, that at least polioviruses attached to suspend- ed particles can be infective for weeks and therefore be transported over long distances. Therefore, the highest risk of virus inputs arise from the large amounts of untreated sewage of the city of Szcze- cin (Poland), which are released into the river Oder and transported to the lagoon and the Baltic Sea. Summer tourism is the most important economical factor in this coastal region and further growth is expected. -

Fish of the Baltic Sea Baltic Herring

Sustainable cuisine of the Southern Baltic region Informational material concerning the cuisine and heritage of the fishing industry, as well as the fish species and attractions of the Southern Baltic region The heritage of coastal fishing as a potential for the development of tourism 1 town Hall in Ustka Ks. Kardynała Stefana Wyszyńskiego 3 Street 76-270 Ustka www.ustka.pl fb/ustkanafali text: Sławomir Adamczak typesetting and graphic design: Grzegorz Myćka photos: potrawy: www.pomorskie-prestige.eu Arkadiusz Szadkowski Tomasz Iwański Agnieszka Szołtysik Magdalena Burduk Joanna Ogórek cover photo: Joanna Ogórek, www.pomorskie-prestige.eu translation: ATOMINIUM, Biuro Tłumaczeń Specjalistycznych publisher: Urząd Miasta Ustka print: Szarek Wydawnictwo Reklama 2 #USTKANAFALI Sustainable cuisine of the Southern Baltic region Baltic Sea / 4 Fish in the Baltic Sea / 6 Traditions of the fishing industry / 8 Attractions in the region / 9 Local fish specialities / 11 3 baltic sea The southern part of the Baltic Sea is surrounded by the coasts of Sweden, Denmark, Germany, Poland, Russia and Lithuania. The region’s largest islands include Oland (Swe- den; 1,342 km2), Rügen (Germany; 935 km2), Bornholm (Denmark; 588 km2), Usedom (Po- land, Germany; 445 km2) and Wolin (Poland; 265 km2). There is also an abundance of smaller islands, such as Fehmarn or Hiddensee (both Germany). The most important fish caught here include cod, herring, sprat, European flounder, salmon, trout and plaice, as well as freshwater species that appear in the waters of the Szczecin, Vis- tula and Curonian Lagoons as well as in the Bays of Puck and Bothnia. 1. Fishing port in Ustka 2. -

Dr Hab. Iwona Jażewicz, Prof. AP

dr hab. Iwona Jażewicz, prof. AP Publikacje 1993: Zmiany koncentracji ludności wiejskiej w województwie słupskim w latach 1970-1990, „Słupskie Prace Mat.- Przyr.” nr 9c, WSP Słupsk, s. 215-231 1994: Struktura własnościowa gruntów sektora publicznego w województwie słupskim i kierunki jej przekształceń w latach 1989-1993, [w:] Falkowski J., Jasiulewicz M. (red.), Restrukturyzacja Państwowych Gospodarstw Rolnych w świetle doświadczeń ogólnokrajowych (ze szczególnym uwzględnieniem woj. koszalińskiego i słupskiego), Materiały XI Ogólnopolskiego Seminarium Geograficzno-Rolniczego w Koszalinie, Koszalin, s. 92-101 1994: Zmiany w funkcjonowaniu przemysłu spożywczego Słupska w latach 1985-1992, [w:] Zioło Z. (red.), Funkcjonowanie przedsiębiorstw przemysłowych w zmieniających się warunkach gospodarowania, „Materiały i Sprawozdania” nr 28, Kraków-Warszawa, s. 132-144, (współautor E. Rydz) 1994: Przemiany struktur przestrzenno-gałęziowych przemysłu województwa słupskiego w zmieniających się warunkach gospodarowania, [w:] Zioło Z. (red.), Zachowanie przestrzenne przemysłu w zmieniających się warunkach gospodarowania, Kraków-Warszawa, s. 125-139, (współautor E. Rydz) 1995: Zmiany substancji mieszkaniowej w miastach Pomorza Środkowego w latach 1970-1988, „Słupskie Prace Mat.-Przyr.” nr 10c, WSP Słupsk, s. 107-123 1996: Przemiany funkcji małych miast Pomorza Środkowego na przykładzie Białego Boru, Kępic i Polanowa, [w:] Rydz E. (red.), Polska w Europie Bałtyckiej, Materiały 45 Zjazdu Polskiego Towarzystwa Geograficznego, Słupsk-Ustka, WSP Słupsk, s. 247-248 1996: Procesy transformacji słupskiego ośrodka przemysłowego w latach 1990-1995, [w:] Zioło Z. (red.) Funkcjonowanie przedsiębiorstw przemysłowych w zmieniających się warunkach gospodarowania, Kraków-Warszawa, s. 47-59, (współautor E. Rydz) 1997: Zachowanie się Stoczni „Ustka” S.A. w okresie przechodzenia do gospodarki rynkowej, [w:] Zioło Z. (red.), Problemy transformacji struktur przemysłowych w procesie przechodzenia do gospodarki rynkowej, Warszawa-Kraków, s. -

Along the Baltic Coast from Świnoujście to Gdańsk - Individual Tour Code OSD 9 Days by Bike, 8 Nights

Along the Baltic coast from Świnoujście to Gdańsk - individual tour Code OSD 9 days by bike, 8 nights • Wandering dunes in Łeba • Guided tour in Gdańsk • about 370 km by bike from 700 Euro Dates 2021 code Start finish OSD-01 4th July 12th July OSD-02 18th July 26th July OSD-03 1st August 9th August OSD-04 15th August 23rd August Your trip begins in Świnoujście, a town at the Polish/German border. The Nature Travel representative will meet you at your hotel's reception at 9 a.m. at day two. You will receive detailed maps and constantly updated descriptions of each part of the route and your bikes. Your luggage will be transported to the next hotel every day. Day one: bicycle free Welcome at the Baltic Sea Individual arrival and accommodation in a guest house in Świnoujście. The town is located on two islands divided by the river Świna. We recommend to have a walk on the beach promenade, to visit the historical City Hall (at present the museum of fishery) and the lighthouse (the highest at the Baltic coast). Accommodation in a guest house in Świnoujście. Day two: ca. 50-68 km by bike Woliński National Park After the breakfast at 9 a.m. the Nature Travel representative will greet you at the reception, you receive the bikes and you begin your first bicycle trip. You will ride along the coast passing through Miedzyzdroje resort and the terrain of Woliński National Park. It is possible to shorten this day's bicycle trip (optional). Accommodation in a hotel in/near Pobierowo. -

Changes in Composition and Distribution of Benthic Algae on The

Changes in O C E A N O L O G IA , No. 33 pp. 183-190, 1992. composition and PL ISSN 0078-3234 distribution of benthic Phytobenthos Southern Baltic algae on the Polish Changes in composition coast of the Baltic Sea (1986- 1991) M a r c i n P l i n s k i , Institute of Oceanography, University of Gdansk, Gdynia J o a n n a T a r a s i u k , TOMASZ JOZWIAK Marine Biology Centre, Polish Academy of Sciences, Gdynia Manuscript received November 5, 1992, in final form April 10, 1993. A b stra ct The composition and frequency of phytobenthic organisms along the Polish Baltic coast was analysed. During 5 years of observations, Chlorophyta were found to be dominant, and the brown alga Pilayella litoralis was expanding rapidly in highly eutrophic areas. Absent at the start of observations, Fucus vesiculosus appeared in some areas in 1990. 1. Introduction Our knowledge of the vegetation on the Polish coast of the Baltic Sea is generally insufficient and only a few aspects have been worked out satisfac torily. The phytoplankton is one of them, as a result of many years’ research at the Marine Fisheries Institute in Gdynia. In addition, the University of Gdansk has recently contributed to this task, although its work has been confined to the Gulf of Gdansk. Finally, the Gdańsk Branch of the Environ mental Protection Institute has been monitoring the Polish economic zone of the Baltic. Our knowledge of the phytobenthos is much poorer. Much of the lit tle work that has been done was incidental to studies of agar-agar stocks. -

MORZE MORZE Krajowe Centrum Organizacji Turnusów

MORZE Darłowo PIRAMIDA I 32 Dźwirzyno WSP OPOLE 55 Jarosławiec ZA WYDMĄ 33 Jastarnia POSEJDON 34 Jastrzębia Góra FENIKS 35 Kołobrzeg DOZAMEL 36 ALBATROS 37 Krynica Morska ZEFIR 38 GÓRNIK 39 Łeba LECH RESORT & SPA 40 ZDROWOTEL 41 ORW 42 Mielno MORZE SYRENA 43 MORZE Mrzeżyno MEDUZA 44 AGADO 45 Sarbinowo FLISAK 46 JAWOR 47 BAŁTYK 48 Stegna FALA 49 BROCH 50 HOTEL USTKA 51 Ustka POMORZE 52 WŁÓKNIARZ 53 Ustronie Morskie ZAGŁĘBIE 54 INTERFERIE CECHSZTYN 55 Władysławowo BURSZTYN / PEKIN 56 KCOTR Krajowe Centrum Organizacji Turnusów Rehabilitacyjnych, tel. 032 259 62 21...5 31 LECZENIE, REHABILITACJA ORAZ WCZASY ZDROWOTNE (+8% VAT) tel. 32 259 62 21...4 Ośrodek Wczasowo-Rehabilitacyjny PIRAMIDA I w Darłowie Rej. OR/24/0004/17 OD/32/0004/17 Czyste powietrze, nieskażona przyroda Darłówko to atrakcyjna dzielnica nadmorska Darłowa na wybrzeżu koszalińskim położona w czystej ekologicznie okolicy. Posiada doskonały mikroklimat stworzony przez morze i lasy iglaste. Walory Darłówka to czyste powietrze nasycone jodkami i mikroelementami, szeroka plaża, oraz cisza i spokój. Ośrodek Piramida I położony jest we wschodniej części Darłówka, nieopodal plaży. ₪ Oferuje: turnusy rehabilitacyjne zwykłe i rozszerzone, prowadzone przez wyspecjalizowaną kadrę, która zapewnia profesjo- nalną obsługę medyczną, pokoje z balkonami, pełnym węzłem sanitarnym, TV i Wi-Fi; zabiegi: laseroterapia, elektrostymulacja, hydromasaż, ultradźwięki, fonoforeza, naświetlania IR, bioptron, inhalacje, talasoterapia, krioterapia, masaż próżniowy, magnetostymulacja, gimnastyka przyrządowa, nordic walking. Za dodatkową opłatą: masaż klasyczny, hipoterapia, okłady fango, terapia manualna. Do dyspozycji: 3 sale wielofunkcyjne wyposażone w sprzęt do prezentacji multimedialnych, gabinet lekarski, liczne gabinety zabiegowe, kryty basen kąpielowy z hydromasażem i podgrzewaną wodą, boiska do gier, ścianka wspinaczkowa dla dzieci. -

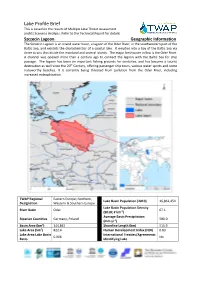

Lake Profile Brief This Is Based on the Results of Multiple Lake Threat Assessment and Its Scenario Analysis

Lake Profile Brief This is based on the results of Multiple Lake Threat Assessment and its Scenario Analysis. Refer to the Technical Report for details. Szczecin Lagoon Geographic Information The Szczecin Lagoon is an inland water basin, a lagoon of the Oder River, in the southwestern part of the Baltic Sea, and exhibits the characteristics of a coastal lake. It empties into a bay of the Baltic Sea via three straits that divide the mainland and several islands. The major freshwater inflow is the Oder River. A channel was opened more than a century ago to connect the lagoon with the Baltic Sea for ship passage. The lagoon has been an important fishing grounds for centuries, and has become a tourist destination as well since the 20th Century, offering passenger ship tours, various water sports and some noteworthy beaches. It is currently being threated from pollution from the Oder River, including increased eutrophication. TWAP Regional Eastern Europe; Northern, Lake Basin Population (2010) 16,862,454 Designation Western & Southern Europe Lake Basin Population Density River Basin Oder 67.1 (2010; # km‐2) Average Basin Precipitation Riparian Countries Germany, Poland 580.0 (mm yr‐1) Basin Area (km2) 144,845 Shoreline Length (km) 515.9 Lake Area (km2) 822.4 Human Development Index (HDI) 0.83 Lake Area:Lake Basin International Treaties/Agreements 0.006 No Ratio Identifying Lake Szczecin Lagoon Basin Characteristics (a) Szczecin Lagoon basin and associated transboundary water systems (b) Szczecin Lagoon basin land use Szczecin Lagoon Threat Ranking A serious lack of global‐scale uniform data on the TWAP transboundary in‐lake conditions required their potential threat risks be estimated on the basis of the characteristics of their drainage basins, rather than in‐lake conditions. -

The Archaeology of the Prussian Crusade

Downloaded by [University of Wisconsin - Madison] at 05:00 18 January 2017 THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE PRUSSIAN CRUSADE The Archaeology of the Prussian Crusade explores the archaeology and material culture of the Crusade against the Prussian tribes in the thirteenth century, and the subsequent society created by the Teutonic Order that lasted into the six- teenth century. It provides the first synthesis of the material culture of a unique crusading society created in the south-eastern Baltic region over the course of the thirteenth century. It encompasses the full range of archaeological data, from standing buildings through to artefacts and ecofacts, integrated with writ- ten and artistic sources. The work is sub-divided into broadly chronological themes, beginning with a historical outline, exploring the settlements, castles, towns and landscapes of the Teutonic Order’s theocratic state and concluding with the role of the reconstructed and ruined monuments of medieval Prussia in the modern world in the context of modern Polish culture. This is the first work on the archaeology of medieval Prussia in any lan- guage, and is intended as a comprehensive introduction to a period and area of growing interest. This book represents an important contribution to promot- ing international awareness of the cultural heritage of the Baltic region, which has been rapidly increasing over the last few decades. Aleksander Pluskowski is a lecturer in Medieval Archaeology at the University of Reading. Downloaded by [University of Wisconsin - Madison] at 05:00 -

Introduction the Genus Aconitum L. (Ranunculaceae Juss.) Is an Interesting Taxonomical Group Which Is Characterized by High Leve

Modern Phytomorphology 9 (Suppl.): 35–73, 2016 SOME NOTES ON THE GENUS ACONITUM IN CHORNOHOra MTS. Andrew V. Novikoff 1*, Józef Mitka 2, Alexander Kuzyarin 1, Oleg Orlov 1, Marina Ragulina 1 Abstract. The paper is a contribution to ecology and chorology ofAconitum in high-mountain zone of the Ukrainian Carpathians. It was confirmed that genusAconitum in the Chornogora mountain range is represented by 14 taxa, and 7 more taxa were listed as potential for this region. These taxa belong to 3 subgenera and are divided on 4 main biomorphological groups delimited on the base of their habitat, life form, ecology and altitudinal distribution. The soil and vegetation types for all taxa have been identified and the maps of their distribution have been prepared. The most influent threats and their categories were identified. Threat category for A. × nanum was changed from DD to VU, and for A. firmum subsp. fussianum from NT to VU. Key words: Aconitum, Chornogora, sozology, ecology, chorology, soils, vegetation 1 State Natural History Museum NAS of Ukraine, Teatralna str. 18, 79008 Lviv, Ukraine; * [email protected] 2 Institute of Botany of Jagiellonian University, Botanical Garden, Jagiellonian University, Kopernika 27, 31-501 Kraków, Poland; [email protected] Introduction (19 confirmed + 3 unconfirmedAconitum taxa) 9 species and subspecies are listed as clearly The genusAconitum L. (Ranunculaceae endemic or subendemic and 2 more hybrid Juss.) is an interesting taxonomical group which subspecies are considered as probably endemic is characterized by high level of morphological (Novikoff & Hurdu 2015). From other side, diversity, presence of a number of subspecific if we consider all forms and varieties then we taxa, and high number of both infra- and can tell about 17 subendemic and endemic taxa interspecific natural hybrids Gáyer( 1922; in general. -

The River Odra Estuary As a Gateway for Alien Species Immigration to the Baltic Sea Basin Das Oderästuar Als Pfad Für Die Einwanderung Von Alienspezies in Die Ostsee

Acta hydrochim. hydrobiol. 27 (1999) 5, 374-382 © WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH, D-69451 Weinheim, 1999 0323 - 4320/99/0509-0374 $ 17.50+.50/0 The River Odra Estuary as a Gateway for Alien Species Immigration to the Baltic Sea Basin Das Oderästuar als Pfad für die Einwanderung von Alienspezies in die Ostsee Dr. Piotr Gruszka Department of Marine Ecology and Environmental Protection, Agricultural University in Szczecin, ul. Kazimierza Królewicza 4/H, PL 71-550 Szczecin, Poland E-mail: [email protected] Summary: The river Odra estuary belongs to those water bodies in the Baltic Sea area which are most exposed to immigration of alien species. Non-indigenous species that have appeared in the Szczecin Lagoon (i.a. Dreissena polymorpha, Potamopvrgus antipodarum, Corophium curvispinum) and in the Pomeranian Bay (Cordylophora caspia, Mya arenaria, Balanus improvisus, Acartia tonsa) in historical time and which now are dominant components of animal communities there as well as other and less abundant (or less common) alien species in the estuary (e.g. Branchiura sowerbyi, Eriocheir sinensis, Orconectes limosus) are presented. In addition, other newcomers - Marenzelleria viridis, Gammarus tigrinus, and Pontogammarus robustoides - found in the estuary in the recent ten years are described. The significance of the sea and inland water transport in the region for introduction of non-indigenous species is discussed against the background of the distribution pattern of these recently introduced polychaete and gammarid species. Keywords: Alien Species, Marenzelleria viridis, Gammarus tigrinus, Pontogammarus robustoides, River Odra Estuary Zusammenfassung: Das Oderästuar gehört zu den Bereichen der Ostsee, die am meisten der Einwanderung von Alienspezies ausgesetzt sind. -

(1957) : Vertical Distribution of World Population

POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES INSTITUTE OF GEOGRAPHY GEOGRAPHICAL STUDIES No 14 JOZEF STASZEWSK1 i l r / VERTICAL DISTRIBUTION OF WORLD POPULATION WARSAW 19 5 7 STATE SCIENTIFIC PUBLISHING HOUSE http://rcin.org.pl POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES INSTITUTE OF GEOGRAPHY * GEOGRAPHICAL STUDIES No 14 http://rcin.org.pl ГЕОГРАФИЧЕСКИЕ ТРУДЫ No 14 ЮЗЕФ СТАШЕВСКИ ВЕРТИКАЛЬНОЕ РАЗМЕЩЕНИЕ НАСЕЛЕНИЯ ЗЕМНОГО ШАРА * PRACE GEOGRAFICZNE No 14 JÓZEF STASZEWSKI PIONOWE ROZMIESZCZENIE LUDNOŚCI NA KULI ZIEMSKIEJ http://rcin.org.pl POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES INSTITUTE OF GEOGRAPHY GEOGRAPHICAL STUDIES No 14 JOZEF STASZEWSKI VERTICAL DISTRIBUTION OF WORLD POPULATION WARSAW 1957 STATE SCIENTIFIC PUBLISHING HOUSE http://rcin.org.pl Editorial Committee Editor-in-Chief: S. LESZCZYCKI Members R. GALON. M. KLIMASZEWSKI, J. KOSTROWICKI, B. OLSZEWICZ, A. WRZOSEK Secretary to the Editorial Committee: A. PUFFOWA Editorial Council J. BARBAG, J. CZYŻEWSKI, J. DYLIK, K. DZIEWOŃSKI, R. GALON, M. KLIMASZEWSKI, J. KONDRACKI, J. KOS- TROWICKI, S. LESZCZYCKI, A. MALICKI, B. OLSZEWICZ, J. WĄSOWICZ, M.KIEŁCZEWSKA-ZALESKA, A. ZIERHOFFER Editor of this Volume M. KIEŁCZEWSKA-ZALESKA http://rcin.org.pl CONTENTS I. Methods of investigations 9 II. Hypsometry of continents H III. Methods of calculating the vertical distribution of population .... 14 IV. Vertical distribution of population by six levels selected 17 1. Survey of distribution throughout the world 17 2. European countries 24 3. The Soviet Union 51 4. Certain countries of Asia 56 5. Certain countries of Africa 68 6. North America "4 7. South America • 79 8. Australia 85 9. Vertical distribution of large towns on the Globe 87 V. Conclusion 90 General Tables 91 References 101 Summary in Polish 105 Summary in Russian 199 List of Tables H3 http://rcin.org.pl http://rcin.org.pl To the memory of my dear wife Julia http://rcin.org.pl http://rcin.org.pl I. -

Polish Yearbook of International Law Vol. XVIII/1989-1990

POLISH YEARBOOK OF INTERNATIONAL LAW XVIII ACADEMIE POLONAISE DES SCIENCES INSTITUT DES SCIENCES JURIDIQUES ANNUAIRE POLONAIS DE DROIT INTERNATIONAL XVIII 1989— 1990 OSSOLINEUM MAISON D’EDITION DE L’ACADEMIE POLONAISE DES SCIENCES Dr. Władysław Czapliński ul. Widawska 7/36 01-494 Warszawa POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES INSTITUTE OF LAW STUDIES POLISH YEARBOOK OF INTERNATIONAL LAW XVIII 1989— 1990 WROCŁAW-WARSZAWA-KRAKÓW ZAKŁAD NARODOWY IMIENIA OSSOLIŃSKICH WYDAWNICTWO POLSKIEJ AKADEMII NAUK 1992 EDITORIAL COMMITTEE * COMITE DE REDACTION Lech Antonowicz, Remigiusz Bierzanek, Wojciech Góralczyk, Roman Jasica, Jerzy Kranz, Manfred Lachs, Jerzy Makarczyk, Janusz Mic- kiewicz, Stanisław E. Nahlik, Jerzy Rajski, Krzysztof Skubiszewski, Janusz Symonides, Andrzej Wasilkowski, Karol Wolike EDITORIAL BOARD • REDACTION Andrzej Wasilkowski (Editor-in-Chief) Jerzy Rajski (Deputy Editor-in-Chief) Renata Szafarz (Deputy Editor-in-Chief) Address of the Editorial Board • Adresse de la Rédaction Institute of Law Studies, Polish Academy of Sciences, Nowy Świat 72, 00-330 Warszawa The typescript of the current issue was handed to the Publisher in December 1989. Contents * Table des matières Articles WŁADYSŁAW CZAPLIŃSKI, The Polish-East German Dispute on the Delimitation of Maritime Areas in the Bay of Pomerania an Appraisal 7 GENOWEFA M. GRABOWSKA, Les avis consultatifs— de la Cour Internationale de Justice 17 RUDOLF OSTRIHANSKY, The “ Mazilu Opinion” of the International Court of Justice and Its Contribution to Clarification of International Law 31 ANNA PRZYBOROWSKA-KLIMCZAK,