The Konkurrenz Group Washington, Dc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ITIF Files Comments Supporting T-Mobile-Sprint Merger

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, DC 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Applications of T-Mobile US, Inc. and Sprint ) WT Docket No. 18-197 Corporation for Consent to Transfer Control of ) Licenses and Authorizations ) OPPOSITION TO PETITIONS TO DENY OF ITIF The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (“ITIF”)1 appreciates this opportunity to comment in support of the pending merger of T-Mobile US, Inc. (“T-Mobile”) and Sprint Corporation (“Sprint”).2 INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY ITIF supports this transaction with the belief that the merger advances innovative wireless broadband services, offers significant benefits that will ultimately flow to consumers, and presents few concerns in terms of competition. The merger offers significant scale and operational efficiencies that will help accelerate the transition to next generation, 5G networks, intensifying competition, and bringing numerous benefits that flow throughout the economy. An honest examination of the facts should find this merger in the public interest under sections 214(a) and 310(d) of the Communications Act.3 Petitions to deny the merger do not fully appreciate the synergies of the transaction and take too myopic a view of how competition functions in today’s media and telecommunications landscape. Some critics of the merger focus narrowly on the number of competitors, decrying this merger as a 4 to 3 reduction. This view does not appreciate companies on the cusp of wireless entry, such as cable firms, or, more importantly, the 1 The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) is a non-partisan research and educational institute – a think tank – whose mission is to formulate and promote public policies to advance technological innovation and productivity internationally, in Washington, and in the states. -

Annual Report 2016

SoftBank Group Corp. ANNUAL REPORT 2016 Corporate Philosophy Information Revolution – Happiness for everyone Vision The corporate group needed most by people around the world SoftBank Group Corp. ANNUAL REPORT 2016 001 A History of Challenges A History of Challenges The view is different when you challenge yourself Continuing to take on new challenges and embrace change without fear. Driving business forward through exhaustive debate. This is the SoftBank Group’s DNA. SoftBank Group Corp. ANNUAL REPORT 2016 002 A History of Challenges Established SoftBank Japan. 1981 Commenced operations as a distributor of packaged software. 1982 Entered the publishing business. Launched Oh! PC and Oh! MZ, monthly magazines introducing PCs and software by manufacturer. 1994 Acquired events division from Ziff Communications Company of the U.S. through SoftBank Holdings Inc. 1996 Acquired Ziff-Davis Publishing Company, U.S. publisher of PC WEEK magazine and provider of leading-edge information on the PC industry. SoftBank Group Corp. ANNUAL REPORT 2016 003 A History of Challenges Established Yahoo Japan through joint investment with Yahoo! Inc. in the U.S. 1996 Began to develop into an Internet company at full scale. Yahoo Japan Net income* 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 FY (Note) Accounting standard: JGAAP up to fiscal 2012; IFRSs from fiscal 2013 onward. * Net income attributable to owners of the parent. SoftBank Group Corp. ANNUAL REPORT 2016 004 A History of Challenges Made full-scale entry into the telecommunications business. 2000s Contributed to faster, more affordable telecommunications services in Japan. -

An Introduction to Network Slicing

AN INTRODUCTION TO NETWORK SLICING An Introduction to Network Slicing Copyright © 2017 GSM Association AN INTRODUCTION TO NETWORK SLICING About the GSMA Future Networks Programme The GSMA represents the interests of mobile operators The GSMA’s Future Networks is designed to help operators worldwide, uniting nearly 800 operators with almost 300 and the wider mobile industry to deliver All-IP networks so companies in the broader mobile ecosystem, including handset that everyone benefits regardless of where their starting point and device makers, software companies, equipment providers might be on the journey. and internet companies, as well as organisations in adjacent industry sectors. The GSMA also produces industry-leading The programme has three key work-streams focused on: events such as Mobile World Congress, Mobile World Congress The development and deployment of IP services, The Shanghai, Mobile World Congress Americas and the Mobile 360 evolution of the 4G networks in widespread use today, Series of conferences. The 5G Journey developing the next generation of mobile technologies and service. For more information, please visit the GSMA corporate website at www.gsma.com. Follow the GSMA on Twitter: @GSMA. For more information, please visit the Future Networks website at: www.gsma.com/futurenetworks With thanks to contributors: AT&T Mobility BlackBerry Limited British Telecommunications PLC China Mobile Limited China Telecommunications Corporation China Unicom Cisco Systems, Inc Deutsche Telekom AG Emirates Telecommunications Corporation (ETISALAT) Ericsson Gemalto NV Hong Kong Telecommunications (HKT) Limited Huawei Technologies Co Ltd Hutchison 3G UK Limited Intel Corporation Jibe Mobile, Inc KDDI Corporation KT Corporation Kuwait Telecom Company (K.S.C.) Nokia NTT DOCOMO, Inc. -

WH Infrastructure Plan Faces GOP Resistance 5G Apple Chips Served

Click here for the online version. This e-mail was created for <<Email Address>> Subscribe • Advertise Tuesday, May 7, 2019 Volume 7 | Issue 89 WH Infrastructure Plan Faces GOP Resistance UPDATE A $2 trillion infrastructure deal outlined last week by President Donald Trump and top Democrats is already losing steam. The tentative deal to repair infrastructure and devote some of the $2 trillion to broadband has run into opposition from Republicans who say it’s too expensive. Those opposed to the deal include Trump's top aide, Mick Mulvaney, and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-KY, who is not in favor of the spending, reports The Washington Post. Mulvaney said Friday, he agrees with the president on a need for an infrastructure package and is trying to identify $1 trillion for that purpose. "Is it difficult to pass any infrastructure bill in this environment, let alone a $2 trillion one, in this environment? Absolutely," Mulvaney said. Continue Reading 5G Apple Chips Served Up By Huawei Apple phones with 5G chips from Chinese telecom giant Huawei? Huawei may be saying, 'why not?,’ reports CNBC. A change in strategy suggests that the company may be receptive to offering its 5G cell phone chips to Apple. At this point, the chips are only available to Huawei cell phone users. At present, Apple does not have 5G capabilities, but has used support technology from Intel and Qualcomm for its smartphones. Apple and Qualcomm are currently engaged in several legal battles involving patent disputes. Although Apple has its own processors and would not need Huawei’s Kirin 980 processor, it may be eyeing Hauweii's 5G chip in lieu of what Qualcomm may have available. -

Natural Disaster Processes

Customer Communication Process for Recovering from Natural Disasters Proprietary Information of Sprint Corporation Recovering from Natural Disasters Introduction This document is intended to provide general overview information of how Sprint prepares for and recovers from disasters such as hurricanes, tornados, flood and acts of terrorism. This document does not detail the actual process of restoring services, but rather it discusses in general terms more how Sprint Local prepares for known storms and how it communicates with its wholesale customers once a natural disaster occurs. Contact Additional contacts for Account Managers, service centers and the provisioning and maintenance center can be located under Customer Contacts at: http://www.sprint.com/localwholesale/ixc.html Document Original release: September 2005 Date Proprietary Information of Sprint Corporation Recovering from Natural Disasters Pre-Planning Hurricanes primarily impact Sprint Local’s service territory from Florida up to North Carolina. In addition, Virginia, Tennessee, Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania and New Jersey will often be impacted by hurricanes after they make land fall. Sprint prepares for hurricane season long before it actually begins and with this foundation in place focuses on the final preparations. Emergency restoration teams hold conference calls and local meetings to map strategies. Activities that occur once a hurricane has the potential to hit Sprint Local’s territory include: • Staging of back-up generators; • Readying extra vehicles; • Fueling cars and trucks; • Verifying batteries are fully charged; • Fueling generators; • Contacting vendors; • Staging of food and water for employees; • Securing additional materials; • Obtaining sandbags and sand; • Developing plans to deploy equipment and personnel to areas likely to experience the most severe damage. -

Page 10 of 10 IRREVOCABLE PROXY

================================================================================ UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 ----------------------- SCHEDULE 13D Under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 SPRINT CORPORATION (Name of Issuer) PCS COMMON STOCK SERIES 1 $1.00 PAR VALUE (Title of Class of Securities) ----------------------- 852061506 (Cusip Number) Comcast Corporation (Name of Person Filing Statement) Arthur R. Block 1500 Market Street Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19102-2148 Tel No.: (215) 665-1700 (Name, Address and Telephone Number of Person Authorized to Receive Notices and Communications) November 23, 1998 (Date of Event which Requires Filing of this Statement) ----------------------- If the filing person has previously filed a statement on Schedule 13G to report the acquisition which is the subject of this Schedule 13D, and is filing this statement because of Rule 13d-1 (e), 13d-1 (f) or 13d-1 (g), check the following: [ ] ================================================================================ CUSIP No. 85206150 13D Page 2 of 10 Pages 1. NAMES OF REPORTING PERSONS I.R.S. IDENTIFICATION NO. OF ABOVE PERSONS (ENTITIES ONLY) COMCAST CORPORATION 2. CHECK THE APPROPRIATE BOX IF A MEMBER OF A GROUP* (a) [ ] (b) [x] 3. SEC USE ONLY 4. SOURCE OF FUNDS OO 5. CHECK BOX IF DISCLOSURE OF LEGAL PROCEEDINGS IS REQUIRED PURSUANT TO ITEMS 2(d) or 2(e) |_| 6. CITIZENSHIP OR PLACE OF ORGANIZATION PENNSYLVANIA NUMBER OF 7. SOLE VOTING POWER 53,479,187 (See Item Nos. 1 and 6) SHARES BENEFICIALLY 8. SHARED VOTING POWER 0 shares OWNED BY EACH 9. SOLE DISPOSITIVE POWER 53,479,187 PCS Common REPORTING Stock-Series-2 $1.00 par PERSON WITH value per share (See Item Nos. 1, 4 and 6) 10. -

STATEMENT of CHAIRMAN AJIT PAI Re

STATEMENT OF CHAIRMAN AJIT PAI Re: Applications of T-Mobile US, Inc., and Sprint Corporation For Consent To Transfer Control of Licenses and Authorizations; Applications of American H Block Wireless L.L.C., DBSD Corporation, Gamma Acquisition L.L.C., and Manifest Wireless L.L.C. for Extension of Time, WT Docket No. 18-197. After a lengthy and painstaking review process, the Commission has correctly concluded that this transaction is in the public interest. In particular, the transaction will help secure United States leadership in 5G, close the digital divide in rural America, and enhance competition in the broadband market. I’ll start with 5G, the next generation of wireless connectivity. This transaction will provide New T-Mobile with the scale and spectrum resources necessary to deploy a robust 5G network across the United States. Specifically, its 5G network will cover 97% of our nation’s population within three years of the closing of the merger and 99% of Americans within six years. What does this mean for American consumers? With New T-Mobile’s network, 90% of Americans would have access to mobile broadband service at speeds of at least 100 Mbps, and 99% would have access to speeds of at least 50 Mbps. In particular, this merger will put critical mid-band spectrum to much more productive use for 5G deployment. New T-Mobile will be far better positioned to deploy Sprint’s extensive 2.5 GHz spectrum holdings than would Sprint standing alone, given that company’s financial situation. Indeed, New T- Mobile’s network will cover at least 88% of Americans with mid-band 5G within six years, a far wider deployment than either Sprint or T-Mobile would be able to accomplish on their own. -

Customer Margins for Onechicago Futures

#XXXXX TO: ALL CLEARING MEMBERS DATE: August 13, 2018 SUBJECT: Customer Margins for OneChicago Futures On a monthly basis OCC updates OneChicago scan ranges used in the OCX SPAN parameter file. The frequency of the updates is intended to keep the futures customer margin rates more closely aligned with clearing margins, while maintaining regulatory minimums related to security futures. This month’s new rates will be effective on Tuesday 8/21. To receive email notification of these rate changes, which includes an attached file of the rate changes, please subscribe to the ONE Updates list from the OFRA webpage: https://www.theocc.com/risk- management/ofra/ The following scan ranges will be updated and all others will not change: Commodity Name Current Scan Code Scan Range Range Effective 8/21/2018 AAN Aarons Inc 23.0 24.2 AAP ADVANCED AUTO PARTS INCCOM 22.0 24.9 AAXN Axon Enterprise, Inc. 25.2 32.8 ABBV Abbvie Inc. 21.4 20.0 ABC AMERISOURCEBERGEN CORP 20.0 22.5 ABX BARRICK GOLD CORP 20.0 24.3 ACAD ACADIA PHARMACEUTICALS 31.5 42.1 ACH ALUMINUM CORP CHINA LTDSPON ADR H SHS 21.1 24.0 AEGN Aegion Corp 22.0 25.2 AEM Agnico Eagle Mines Limited 20.0 21.1 AEO AMERICAN EAGLE OUTFITTERS NECOM 20.0 21.2 AFSI AMTRUST FINANCIAL SERVICES ICOM 30.2 35.1 AGIO AGIOS PHARMACEUTICALS INCCOM 30.7 33.7 AGX ARGAN INCCOM 27.3 35.7 AKAM AKAMAI TECHNOLOGIES INCCOM 20.0 22.1 AKRX AKORN INCCOM 38.2 40.7 AKS AK STL HLDG CORP 34.3 38.0 ALKS Alkermes plc 27.4 39.1 ALNY ALNYLAM PHARMACEUTICALS INCCOM 46.5 54.1 ALXN ALEXION PHARMACEUTICALS INC 21.1 22.8 AMAG AMAG Pharmaceuticals Inc 34.4 43.6 AMBA AMBARELLA INCSHS 27.7 32.5 AMD ADVANCED MICRO DEVICES INC 31.7 34.5 AMED AMEDISYS INCCOM 21.9 24.2 AMN AMN HEALTHCARE SERVICES INCCOM 23.2 26.1 AMWD AMERICAN WOODMARK CORPCOM 40.4 26.9 ANET ARISTA NETWORKS INCCOM 24.7 28.3 ANF ABERCROMBIE & FITCH CO 34.8 38.9 AOBC American Outdoor Brands Corporation 22.7 24.6 APEI AMERICAN PUBLIC EDUCATION INCOM 37.0 40.8 APOG APOGEE ENTERPRISES INCCOM 20.0 23.0 ARCO ARCOS DORADOS HOLDINGS INC 22.4 24.4 ATGE Adtalem Global Education Inc. -

Starburst II, Inc. and Sprint Nextel Corporation (Commission File No

2000 PENNSYLVANIA AVE., NW M O R RI S O N & F O E R S T E R L L P WASHINGTON, D.C. NE W Y O RK , S AN F R AN CI SCO , LO S AN GE LE S, P AL O AL T O , 20006-1888 S AN DI E GO , WA SH I N GT ON , D . C . NO R T H E R N V I R G I NI A , DEN VER , TELEPHONE: 202.887.1500 S AC R AM E N T O , W A LN U T CR EEK FACSIMILE: 202.887.0763 T OKY O, L O NDO N , B RU S S E L S , B E IJIN G , S H AN G H AI , H O NG K O N G WWW.MOFO.COM Writer’s Direct Contact 202.887.1563 [email protected] July 2, 2013 Securities Exchange Act of 1934—Rules 12g-3(a) and 12b-2 Securities Act of 1933—Rule 414 Securities Act of 1933—Forms S-3, S-4, and S-8 Securities Act of 1933—Rule 144 Securities Act of 1933—Section 4(3) and Rule 174 Office of Chief Counsel Division of Corporation Finance Securities and Exchange Commission 100 F. Street, N.E. Washington, D.C. 20549 RE: Starburst II, Inc. and Sprint Nextel Corporation (Commission File No. 001-04721) Ladies and Gentlemen: We are counsel to Starburst II, Inc., a Delaware corporation (“New Sprint”) and New Sprint’s wholly owned subsidiary, Starburst III, Inc., a Kansas corporation (“Merger Sub”), and on behalf of such entities and Sprint Nextel Corporation, a Kansas corporation (“Sprint”), request advice of the staff of the Division of Corporation Finance (the “Staff”) of the Securities and Exchange Commission (the “Commission”) with respect to a number of succession-related issues under the Securities Act of 1933, as amended (the “Securities Act”), and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, as amended (the “Exchange Act”), arising out of a proposed plan to: (i) consummate a merger transaction, pursuant to which Merger Sub will merge with and into Sprint, with Sprint surviving the merger as a wholly owned subsidiary of New Sprint (the “Sprint Merger”) pursuant to that certain agreement and plan of merger by and among SoftBank Corp., a Japanese kabushiki kaisha (“SoftBank”), Sprint, Starburst I, Inc. -

Sprint 401(K) Plan Summary Plan Description Table of Contents

Sprint 401(k) Plan Summary Plan Description Table of Contents Answering your needs 3 How The Plan is administered 13 Plan financing 14 A quick look at the Plan 3 Special rules for “top heavy” plans 14 Who can join the 401(k) Plan 4 Future of the Plan 14 Eligibility 4 The Plan and ERISA/Your ERISA Rights 15 Enrollment 4 Restrictions on re-offer or resale of Sprint stock 16 Accessing your plan account 4 Naming beneficiaries 4 Information incorporated by reference 16 Plan contributions 5 Participating employers of the Plan 17 Your own contributions 5 Important definitions 17 Catch-up contributions 5 Company matching contributions 5 History of the Plan 18 Vesting of company matching contributions 6 Sprint 401(k) Plan 18 Voting rights 6 Centel Plan 18 Rollover contributions 6 Sprint PCS Plan 18 Changing or stopping your plan contributions 7 U.S. Sprint Plan 18 Tax advantages 7 TRASOP 18 Merged Plan 18 Investing your account 7 Provisions for Special Loan to the Plan (LESOP) 18 Your investment election 7 Recombination of Sprint FON Stock Fund and 19 Performance record of investment funds 7 Sprint PCS Stock Fund 19 Changing your investments 7 Freezing of the Company Stock Fund 19 Short-term trading 8 Spinoff to Embarq Retirement Savings Plan 19 Transfers from the Company Stock Fund 8 Appendix A: Special Rules for Certain Former 20 Compliance with Section 404(c) of ERISA 8 Participants in the U.S. Sprint Savings and Loans from your account 8 Investment Plan Appendix B: Special rules for certain former 20 Withdrawals while you are still working 9 participants in the Centel Retirement Savings In-service withdrawals 9 Plan Hardship withdrawals 10 Appendix C: Special rules for certain former 20 Other withdrawals 10 participants in the Sprint Spectrum Savings and Retirement Plan Plan distributions 11 Appendix D: Special rules for certain participants 21 Your own contributions 11 in the Sprint Retirement Savings Plan prior to Jan. -

Review of Operations

REVIEW OF OperatiONS PUBLIC BUSINESS NEC provides safe, secure and efficient social solutions Tomonori Nishimura for domestic and foreign governments, governmental Executive Vice President agencies, public institutions, financial institutions and other organizations by combining its distinctive technology assets, including networking and sensing technologies, with broad systems integration expertise and customer assets. SALES OPERATING INCOME, business, NEC and INTERPOL signed a partnership OPERATING INCOME RATIO agreement for strengthening measures to fight (Billion ¥) (Billion ¥) 800.0 60.0 increasingly complex and sophisticated cybercrime. 680.7 649.5 49.0 The two partners will work together on state-of-the-art 43.3 cyber security measures. 600.0 40.0 In the public services sector, sales remained strong in 7.2% the fire and disaster prevention area on the back of 6.7% 400.0 continued high demand due to regional enlargement 20.0 and digitization of wireless communication networks. 200.0 NEC also steadily built on its track record in the integration of cloud computing platforms and provision of services for local governments, schools, libraries and 0 2012 2013 0 2012 2013 Operating income other customers. In addition, NEC implemented a new Operating income ratio traffic management system that enables the real-time provision of traffic information thanks to the high-speed Fiscal 2013 Performance and Main processing of Big Data for the Shin-Tomei Expressway Accomplishments operated by Central Nippon Expressway Company Business segment sales increased 4.8% year on year Limited. And NEC delivered a new train wireless system to ¥680.7 billion. This increase mainly reflected steady to Odakyu Electric Railway Co., Ltd. -

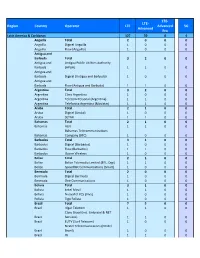

Prepared for Upload GCD Wls Networks

LTE‐ LTE‐ Region Country Operator LTE Advanced 5G Advanced Pro Latin America & Caribbean 127 50 0 4 Anguilla Total 20 0 0 Anguilla Digicel Anguilla 10 0 0 Anguilla Flow (Anguilla) 10 0 0 Antigua and Barbuda Total 32 0 0 Antigua and Antigua Public Utilities Authority Barbuda (APUA) 11 0 0 Antigua and Barbuda Digicel (Antigua and Barbuda) 10 0 0 Antigua and Barbuda Flow (Antigua and Barbuda) 11 0 0 Argentina Total 32 0 0 Argentina Claro Argentina 10 0 0 Argentina Telecom Personal (Argentina) 11 0 0 Argentina Telefonica Argentina (Movistar) 11 0 0 Aruba Total 21 0 0 Aruba Digicel (Aruba) 10 0 0 Aruba SETAR 11 0 0 Bahamas Total 21 0 0 Bahamas ALIV 11 0 0 Bahamas Telecommunications Bahamas Company (BTC) 10 0 0 Barbados Total 31 0 0 Barbados Digicel (Barbados) 10 0 0 Barbados Flow (Barbados) 11 0 0 Barbados Ozone Wireless 10 0 0 Belize Total 21 0 0 Belize Belize Telemedia Limited (BTL, Digi) 11 0 0 Belize SpeedNet Communications (Smart) 10 0 0 Bermuda Total 20 0 0 Bermuda Digicel Bermuda 10 0 0 Bermuda One Communications 10 0 0 Bolivia Total 31 0 0 Bolivia Entel Movil 11 0 0 Bolivia NuevaTel PCS (Viva) 10 0 0 Bolivia Tigo Bolivia 10 0 0 Brazil Total 75 0 0 Brazil Algar Telecom 11 0 0 Claro Brasil (incl. Embratel & NET Brazil Servicos) 11 0 0 Brazil EUTV (Surf Telecom) 10 0 0 Nextel Telecomunicacoes (Nextel Brazil Brazil) 10 0 0 Brazil Oi 11 0 0 Brazil Telefonica Brasil (Vivo) 11 0 0 Brazil TIM Participacoes (TIM Brasil) 11 0 0 Cayman Islands Total 20 0 0 Cayman Islands Digicel (Cayman Islands) 10 0 0 Cayman Islands Flow (Cayman Islands) 10