Net Metering Programs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Smart Metering and Smart Charging May Help a Local Energy Community in Collective Self-Consumption in Presence of Electric Vehicles

energies Article How Smart Metering and Smart Charging may Help a Local Energy Community in Collective Self-Consumption in Presence of Electric Vehicles Giuseppe Barone 1 , Giovanni Brusco 1 , Daniele Menniti 1 , Anna Pinnarelli 1 , Gaetano Polizzi 1, Nicola Sorrentino 1, Pasquale Vizza 1 and Alessandro Burgio 2,* 1 Department of Mechanical, Energy and Management Engineering, University of Calabria, 87036 Rende, Italy; [email protected] (G.B.); [email protected] (G.B.); [email protected] (D.M.); [email protected] (A.P.); [email protected] (G.P.); [email protected] (N.S.); [email protected] (P.V.) 2 Independent Researcher, 87036 Rende, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 11 July 2020; Accepted: 4 August 2020; Published: 12 August 2020 Abstract: The 2018/2001/EU renewable energy directive (RED II) underlined the strategic role of energy communities in the EU transition process towards sustainable and renewable energy. In line with the path traced by RED II, this paper proposes a solution that may help local energy communities in increasing self-consumption. The proposed solution is based on the combination of smart metering and smart charging. A set of smart meters returns the profile of each member of the community with a time resolution of 5 s; the aggregator calculates the community profile and regulates the charging of electric vehicles accordingly. An experimental test is performed on a local community composed of four users, where the first is a consumer with a Nissan Leaf, whereas the remaining three users are prosumers with a photovoltaic generator mounted on the roof of their home. -

Italy's Effort to Phase out and Rationalise Its Fossil Fuel Subsidies

ITALY’S EFFORT TO PHASE OUT AND RATIONALISE ITS FOSSIL-FUEL SUBSIDIES A REPORT ON THE G20 PEER-REVIEW OF INEFFICIENT FOSSIL-FUEL SUBSIDIES THAT ENCOURAGE WASTEFUL CONSUMPTION IN ITALY PREPARED BY THE MEMBERS OF THE PEER-REVIEW TEAM: ARGENTINA, CANADA, CHILE, CHINA, FRANCE, GERMANY, INDONESIA, NETHERLANDS, NEW ZEALAND, IEA, UN ENVIRONMENT, IISD, EUROPEAN ENERGY RETAILERS, GREEN BUDGET EUROPE, THE OECD (CHAIR OF THE PEER-REVIEW) AND SELECTED EXPERTS APRIL 2019 1 │ Italy’s effort to phase out and rationalise its fossil-fuel subsidies A report on the G20 peer-review of inefficient fossil-fuel subsidies that encourage wasteful consumption in Italy Prepared by the members of the peer-review team: Argentina, Canada, Chile, China, France, Germany, Indonesia, Netherlands, New Zealand, IEA, UN Environment, IISD, European Energy Retailers, Green Budget Europe, the OECD (Chair of the peer-review) and selected experts ITALY’S EFFORT TO PHASE OUT AND RATIONALISE ITS FOSSIL FUEL SUBSIDIES 2 │ Table of contents Acronyms and Abbreviations ............................................................................................................... 4 Executive Summary .............................................................................................................................. 5 1. Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 7 1.1. Background and context .............................................................................................................. -

Propane & Net Zero

PROPANE & NET ZERO WHY NET ZERO IS IMPORTANT “Net zero” refers to achieving an overall balance between emissions produced and emissions taken out of the atmosphere. Propane can help reduce CO2 emissions by replacing heavy carbons like coal, oil and even wood. Its affordability also ensures every consumer can share equitably in the benefits propane brings. PROPANE DECARBONIZES PROPANE ENSURES EQUITY Clean and renewable energy like propane Access to clean, affordable and renewable energy accelerates decarbonization. like propane ensures equity on the path to zero. Δ Decarbonization requires more cleaner energy options. The Δ Urban and rural low-income households, especially U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Office of Scientific and African American and Latinx households, spend roughly Technical Information says that large emissions reductions three times as much of their income on energy costs are achievable through a broad range of opportunities, as non-low-income households. In February 2021, EIA including the use of low- or zero-carbon alternatives. reported that electricity was 68% more expensive per million BTUs than propane. Δ The electric grid isn’t always the cleanest answer. Currently, propane-fueled medium- and heavy-duty Δ Energy should be affordable, so that no one has to vehicles provide a lower carbon footprint solution in 38 go without, but the share of income that low-income U.S. states when compared to medium- and heavy-duty households spent on electricity rose by 1/3 in the last EVs charged from the electrical grid. decade. Δ Propane is innovating everyday. It is, in fact, the new Δ Everyone should have access to clean energy and home diesel. -

An Overview of Behind-The-Meter Solar-Plus-Storage

AN OVERVIEW OF BEHIND-THE- METER SOLAR-PLUS-STORAGE REGULATORY DESIGN Approaches and Case Studies to Inform International Applications Owen Zinaman, Thomas Bowen, and Alexandra Aznar National Renewable Energy Laboratory March 2020 A product of the USAID-NREL partnership Contract No. IAG-17-2050 NOTICE This work was authored, in part, by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), operated by Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC, for the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) under Contract No. DE- AC36-08GO28308. Funding provided by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) under Contract No. IAG-17-2050. The views expressed in this report do not necessarily represent the views of the DOE or the U.S. Government, or any agency thereof, including USAID. This report is available at no cost from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) at www.nrel.gov/publications. U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) reports produced after 1991 and a growing number of pre-1991 documents are available free via www.OSTI.gov. Cover photo from iStock 471670114. NREL prints on paper that contains recycled content. Acknowledgments The authors thank Anurag Mishra and Sarah Lawson from the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) Office of Energy and Infrastructure for their support of this work. We also wish to thank the following individuals for their detailed review comments, insights, and contributions to this report (names listed alphabetically by organization and last name). Clean Energy Group—Seth Mullendore E3 Analytics—Toby -

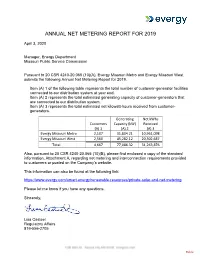

Annual Net Metering Report for 2019

ANNUAL NET METERING REPORT FOR 2019 April 3, 2020 Manager, Energy Department Missouri Public Service Commission Pursuant to 20 CSR 4240-20.065 (10)(A), Evergy Missouri Metro and Evergy Missouri West submits the following Annual Net Metering Report for 2019. Item (A) 1 of the following table represents the total number of customer-generator facilities connected to our distribution system at year end. Item (A) 2 represents the total estimated generating capacity of customer-generators that are connected to our distribution system. Item (A) 3 represents the total estimated net kilowatt-hours received from customer- generators. Generating Net kWhs Customers Capacity (kW) Received (A) 1 (A) 2 (A) 3 Evergy Missouri Metro 2,107 31,804.21 10,961,098 Evergy Missouri West 2,560 45,282.12 20,302,687 Total 4,667 77,086.32 31,263,876 Also, pursuant to 20 CSR 4240-20.065 (10)(B), please find enclosed a copy of the standard information, Attachment A, regarding net metering and interconnection requirements provided to customers or posted on the Company’s website. This information can also be found at the following link: https://www.evergy.com/smart-energy/renewable-resources/private-solar-and-net-metering Please let me know if you have any questions. Sincerely, Lisa Casteel Regulatory Affairs 816-556-2705 Public Attachment A Public FILED Missouri Public Service Commission EE-2019-0056; JE-2019-0028 FILED Missouri Public Service Commission EE-2019-0056; JE-2019-0028 FILED Missouri Public Service Commission EE-2019-0056; JE-2019-0028 KCP&L GREATER MISSOURI OPERATIONS COMPANY P.S.C. -

GHG Protocol Scope 2 Guidance

GHG Protocol Scope 2 Guidance An amendment to the GHG Protocol Corporate Standard AUTHOR Mary Sotos GHG PROTOCOL TEAM Pankaj Bhatia, World Resources Institute Cynthia Cummis, World Resources Institute Mark Didden, World Business Council for Sustainable Development Alex Kovac, World Resources Institute Josh Ryor, World Resources Institute Amanda Stevens, World Resources Institute Table of Contents 1 Introduction 4 2 Business Goals 14 3 Accounting and Reporting Principles 20 4 Scope 2 Accounting Methods 24 5 Identifying Scope 2 Emissions and Setting the Scope 2 Boundary 32 6 Calculating Emissions 42 7 Accounting and Reporting Requirements 58 8 Recommended Reporting on Instrument Features and Policy Context 66 9 Setting Reduction Targets and Tracking Emissions Over Time 74 BACKGROUND READING 10 Key Concepts and Background in Energy Attribute Certificates and Claims 78 11 How Companies Can Drive Electricity Supply Changes with the Market-Based Method 88 AppENDICES A Accounting for Steam, Heat, and Cooling 94 B Accounting for Energy-Related Emissions Throughout the Value Chain 96 Abbreviations 98 Glossary 99 References 108 Recognitions 111 1 Detailed Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION 4 4 SCOPE 2 ACCOUNTING METHODS 24 1.1 The GHG Protocol 5 4.1 Approaches to accounting scope 2 25 1.2 The Corporate Standard’s 4.2 Emission rate approach 27 approach to scope 2 emissions 5 4.3 The decision-making value of each 1.3 Key questions on scope 2 accounting method’s results 28 and reporting 6 1.4 Purpose of this Guidance 7 5 IDENTIFYING SCOPE 2 EMISSIONS -

USAID Energy Storage Decision Guide for Policymakers

USAID ENERGY STORAGE FOR DECISION GUIDE POLICYMAKERS www.greeningthegrid.org | www.nrel.gov/usaid-partnership USAID ENERGY STORAGE FO R DECISION GUIDE P OLICYMAKERS Authors Ilya Chernyakhovskiy, Thomas Bowen, Carishma Gokhale-Welch, Owen Zinaman National Renewable Energy Laboratory July 2021 View the companion report: USAID Grid-Scale Energy Storage Technologies Primer www.greeningthegrid.org | www.nrel.gov/usaid-partnership Prepared by NOTICE This work was authored, in part, by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), operated by Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC, for the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) under Contract No. DE-AC36-08GO28308. Funding provided by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) under Contract No. IAG-17-2050. The views expressed in this report do not necessarily represent the views of the DOE or the U.S. Government, or any agency thereof, including USAID. This report is available at no cost from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) at www.nrel.gov/publications. U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) reports produced after 1991 and a growing number of pre-1991 documents are available free via www.OSTI.gov. Front cover: photo from iStock 506609532; Back cover: photo from iStock 506611252 NREL prints on paper that contains recycled content. Acknowledgments The authors are greatly indebted to several individuals for their support and guidance. We wish to thank Sarah Lawson, Andrew Fang, and Sarah Dimson at the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) for their thoughtful reviews. We also wish to thank Peerapat Vithayasrichareon, Jacques Warichet, Enrique Gutierrez Tavarez, and Luis Lopez at the International Energy Agency, and Dr. -

Net Metering: in Brief

Net Metering: In Brief November 14, 2019 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46010 SUMMARY R46010 Net Metering: In Brief November 14, 2019 Net metering is a policy that allows electricity customers with their own generation capacity to be financially compensated for the energy they produce. Net metering is widely regarded as having Ashley J. Lawson an important role in deployment of distributed generation (DG), especially solar energy. State Analyst in Energy Policy and local governments have authority to establish net metering policies, and some have done so for many years. Congress took action to encourage net metering in the Energy Policy Act of 2005 (EPACT05), and the policy now exists, in some form, in 45 states. Recent state net metering policy modifications, and potential effects on solar energy deployment, may be relevant to congressional discussions regarding the role of renewable energy sources in the nation’s electricity system. Solar photovoltaic panels (e.g., rooftop solar) accounted for 97% of the generation capacity participating in net metering programs in 2018. Net metering participation roughly quadrupled from 2013 to 2018, according to data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration. Hawaii has the highest participation rate of any state, with 15% of electricity customers participating in net metering in 2018. In a majority of states, however, net metering customers account for less than 1% of total electricity customers. States differ in the way net metering customers are compensated. A common method is the retail rate, under which energy from net metering capacity offsets energy consumed from the grid in a one-to-one fashion. -

Comparative Analysis of Net Metering and Feed in Tariff Schemes for 50Kw Solar Photovoltaic Distributed Generation System at Mahad Ganesh Dahale*, Prof

IJRECE VOL. 6 ISSUE 2 APR.-JUNE 2018 ISSN: 2393-9028 (PRINT) | ISSN: 2348-2281 (ONLINE) Comparative Analysis of Net Metering and Feed in Tariff Schemes for 50kw Solar Photovoltaic Distributed Generation System at Mahad Ganesh Dahale*, Prof. Sunil Gaikwad and Prof. Dr. Y.P. Nerkar Department of Electrical Engineering, PVG's COET, Pune, India Abstract: Solar Photovoltaic (PV) system compared to its takes place through grid. Feed in tariff (FiT) or renewable scenario a decade ago has made a great impact in energy energy payment method is applied to those distributed energy production. Government provides several benefits to the systems producing electricity by their own. FiT has two tariffs customers in terms of subsidies, benefits in income-taxes and i.e. for its generation and its own consumption.Both methods many other such benefits. Tariff by Net metering i.e. Net metering and FiT prove to be cost and energy effective schemeregulated by the Government provides benefits to the and provide reduction in CO2 emission. However, the latter consumer applicable for various distributed generation system. provides more effective result in terms of cost and energy. In this paper, a new scheme of Feed in Tariff (FiT) for metering the total amount of energy generated has been This paper provides the statistical analysis between Net metering and Feed in Tariff applied on a 50kWp solar roof top discussed. A case study on 50 kW Laxmi Ice factory at Mahad, Maharashtra is considered in this paper. A PV application. This is applied at Laxmi Ice Factory in Mahad, Maharashtra at an altitude 11m and latitude 18.1N and MATLAB/Simulink model consisting 50 kW solar PV system, FiT& Net metering, solar radiance value is simulated. -

REFORMING NET METERING Tom Tanton PROVIDING a BRIGHT and EQUITABLE FUTURE

ALEC.ORG REFORMING NET METERING Tom Tanton PROVIDING A BRIGHT AND EQUITABLE FUTURE WWW.ALEC.ORG 1 About the American Legislative Exchange Council The American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) is the nation’s largest nonpartisan, individual membership organization of state legislators, with more than 2,000 members across the nation. ALEC is committed to advancing the fundamental principles of limited government, free markets and federalism at the state level through a nonpartisan public-private partnership of America’s state legislators, members of the private sector, and the general public. ALEC is classified by the Internal Revenue Service as a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, public policy, and educational organization. Individuals, philanthropic foundations, corporations, companies, or associations are eligible to support ALEC’s work through tax-deductible gifts. About the ALEC Task Force on Energy, Environment and Agriculture The ALEC Task Force on Energy, Environment and Agriculture promotes the mutually beneficial link between a robust economy and a healthy environment, and seeks to enhance the quality and use of our natural and agricultural resources for the benefit of human health and well-being. The Task Force works with more than 250 public and private-sector members to develop best practice model policy on issues such as climate change, agriculture, environmental health, regulatory reform, federalism, chemical regulation, property rights, waste management, and public lands. John Eick is the task force director and can be reached at -

DC Power Production, Delivery and Utilization

DDCC PPowerower PProduction,roduction, DDeliveryelivery aandnd UUtilizationtilization An EPRI White Paper June 2006 AAnn EEPRIPRI WWhitehite PPaperaper DC Power Production, Delivery and Utilization This paper was prepared by Karen George of EPRI Solutions, Inc., based on technical material from: Arshad Mansoor, Vice President, EPRI Solutions Clark Gellings, Vice President—Innovation, EPRI Dan Rastler, Tech Leader, Distributed Resources, EPRI Don Von Dollen, Program Director, IntelliGrid, EPRI AAcknowledgementscknowledgements We would like to thank reviewers and contributors: Phil Barker, Principal Engineer, Nova Energy Specialists David Geary, Vice President, of Engineering, Baldwin Technologies, Inc. Haresh Kamath, EPRI Solutions Tom Key, Principal Technical Manager, EPRI Annabelle Pratt, Power Architect, Intel Corporation Mark Robinson, Vice President, Nextek Power Copyright ©2006 Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI), Palo Alto, CA USA June 2006 Page 2 AAnn EEPRIPRI WWhitehite PPaperaper DC Power Production, Delivery and Utilization Edison Redux: The New AC/DC Debate Thomas Edison’s nineteenth-century electric distribution sys- Several converging factors have spurred the recent interest in tem relied on direct current (DC) power generation, delivery, DC power delivery. One of the most important is that an in- and use. This pioneering system, however, turned out to be im- creasing number of microprocessor-based electronic devices practical and uneconomical, largely because in the 19th cen- use DC power internally, converted inside the device from tury, DC power generation was limited to a relatively low volt- standard AC supply. Another factor is that new distributed re- age potential and DC power could not be transmitted beyond sources such as solar photovoltaic (PV) arrays and fuel cells a mile. -

Net Metering Policy Summary

Net Metering Policy Summary State Authority Capacity Limits Carry‐over of Surcharge or Avoided Community Multiple Application NEG additional cost Cost or or virtual net accounts for connection Retail Rate metering (aggregate) for NEG Montana 69‐8‐601 50 kW Month‐to‐ No, prohibited in Retail No No IOUs that through month. Credit statute have 69‐8‐605, to utility at restructured MCA the end of in accordance the year with Title 69, chapter 8 Wyoming 37‐16‐ 25 kW Month‐to‐ No, prohibited in Month‐to‐ No No IOUs, electric 101 month. Credit statute month cooperatives, through to customer credited per and irrigation 37‐16‐ at the end of kWh at retail districts 104, WS the year rate*. Annually utility purchases at avoided‐cost rate Idaho Tariff 25 kW for Month‐to‐ $100 application Residential No May transfer IOUs have residential and month. fee. Net metering and small excess developed a (Idaho small Excess credits tariff — including commercial generation tariff to allow Power as commercial carry forward current rate customers, between net metering example. indefinitely structure and credited at meters that is Schedule 100 kW for until entirely interconnection retail rate. among approved by 84.) other rate used to offset requirements — Large customer the PUC classes consumption does not commercial accounts if represent and meters are Utility tariffs guarantee of agricultural on same limit to 0.1% in future pricing customers, primary baseline year credited at feeder, 85% located on avoided‐cost same rate contiguous property, and electricity is for customer Nevada NRS 1 MW Month‐to‐ For systems up to Either a No Hydro with a IOUs 704.766 – month or 25 kW, utility standard capacity up 704.775 Generation time of use.