GHG Protocol Scope 2 Guidance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carbon Price Floor Consultation: the Government Response

Carbon price floor consultation: the Government response March 2011 Carbon price floor consultation: the Government response March 2011 Official versions of this document are printed on 100% recycled paper. When you have finished with it please recycle it again. If using an electronic version of the document, please consider the environment and only print the pages which you need and recycle them when you have finished. © Crown copyright 2011 You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or e-mail: [email protected]. ISBN 978-1-84532-845-0 PU1145 Contents Page Foreword 3 Executive summary 5 Chapter 1 Government response to the consultation 7 Chapter 2 The carbon price floor 15 Annex A Contributors to the consultation 21 Annex B HMRC Tax Impact and Information Note 25 1 Foreword Budget 2011 re-affirmed our aim to be the greenest Government ever. The Coalition’s programme for Government set out our ambitious environmental goals: • introducing a floor price for carbon • increasing the proportion of tax revenues from environmental taxes • making the tax system more competitive, simpler, fairer and greener This consultation response demonstrates the significant progress the Coalition Government has already made towards these goals. As announced at Budget 2011, the UK will be the first country in the world to introduce a carbon price floor for the power sector. -

The Essential Guide to Small Scale Combined Heat and Power

The essential guide to small scale February 2018 combined heat and power The answer to all your combined heat and power questions in one, easy to read guide... Centrica Business Solutions The essential guide to combined heat and power Contents What is combined heat and power? 4 • About Centrica Business Solutions • Introduction to combined heat and power • Combined heat and power applications • Fuel options • Benefits of combined heat and power Economics of combined heat and power 6 • Stages of feasibility • CHP quality index • CHP selection • Site review to determine actual installation costs Financing the CHP project 10 • Discount energy purchase (DEP) • Capital purchase scheme • Energy savings agreement (ESAs) Integrating CHP into a building 11 • Low temperature hot water systems • Steam systems • Absorption cooling systems CHP technology 12 • The equipment • E-POWER Typical case studies 15 • Alton Towers • Newcastle United • Royal Stoke University Hospital Glossary of terms 18 CIBSE accredited CPD courses 19 Useful contacts and further information 20 2 Centrica Business Solutions ThePanoramic essential Power guide in to action combined heat and power About Centrica Business Solutions With over 30 years’ experience, more than 3,000 units manufactured and an amazing 27 millions tonnes of CO2 saved by our customers, Centrica Business Solutions are the largest provider of small scale CHP units in the U.K. We understand the power of power. As new energy sources and technologies emerge, and power becomes decentralised, we’re helping organisations around the world use the freedom this creates to achieve their objectives. We provide insights, expertise and solutions to enable them to take control of energy and gain competitive advantage – powering performance, resilience and growth. -

Who Pays? Consumer Attitudes to the Growth of Levies to Fund Environmental and Social Energy Policy Objectives Prashant Vaze and Chris Hewett About Consumer Focus

Who Pays? Consumer attitudes to the growth of levies to fund environmental and social energy policy objectives Prashant Vaze and Chris Hewett About Consumer Focus Consumer Focus is the statutory Following the recent consumer and consumer champion for England, Wales, competition reforms, the Government Scotland and (for postal consumers) has asked Consumer Focus to establish Northern Ireland. a new Regulated Industries Unit by April 2013 to represent consumers’ interests in We operate across the whole of the complex, regulated markets sectors. The economy, persuading businesses, Citizens Advice service will take on our public services and policy-makers to role in other markets from April 2013. put consumers at the heart of what they do. We tackle the issues that matter to Our Annual Plan for 2012/13 is available consumers, and give people a stronger online, consumerfocus.org.uk voice. We don’t just draw attention to problems – we work with consumers and with a range of organisations to champion creative solutions that make a difference to consumers’ lives. For regular updates from Consumer Focus, sign up to our monthly e-newsletter by emailing [email protected] or follow us on Twitter http://twitter.com/consumerfocus Consumer Focus Contents Executive summary .................................................................................................... 4 1 Introduction .............................................................................................................. 8 Background .............................................................................................................. -

An International Comparison of Energy and Climate Change Policies Impacting Energy Intensive Industries in Selected Countries

AN INTERNATIONAL COMPARISON OF ENERGY AND CLIMATE CHANGE POLICIES IMPACTING ENERGY INTENSIVE INDUSTRIES IN SELECTED COUNTRIES Final Report 11 JULY 2012 The Views expressed within this report are those of the authors and should not be treated as Government policy An international comparison of energy and climate change policies impacting energy intensive industries in selected countries FINAL REPORT 11 July 2012 Submitted to: Department for Business Innovation & Skills 1 Victoria Street London SW1H 0ET Submitted by: ICF International 3rd Floor, Kean House 6 Kean Street London WC2B 4AS U.K. An international comparison of energy and climate change policies impacting energy intensive industries in selected countries Table of Contents Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................... 1 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 17 1.1 BACKGROUND .............................................................................................. 17 1.2 OBJECTIVES AND SCOPE ............................................................................... 18 2. ELECTRICITY AND GAS MARKETS .............................................................. 20 3. QUALITATIVE ANALYSIS OF ENERGY AND CLIMATE CHANGE POLICIES TOWARDS KEY SECTORS IN EACH COUNTRY .................................................. 35 3.1 METHODOLOGY ............................................................................................ 35 3.1.1 -

Reforming the Electricity Market

HOUSE OF LORDS Select Committee on Economic Affairs 2nd Report of Session 2016–17 The Price of Power: Reforming the Electricity Market Ordered to be printed 8 February 2017 and published 24 February 2017 Published by the Authority of the House of Lords HL Paper 113 Select Committee on Economic Affairs The Economic Affairs Committee was appointed by the House of Lords in this session “to consider economic affairs”. Membership The Members of the Select Committee on Economic Affairs are: Baroness Bowles of Berkhamsted Lord Layard Lord Burns Lord Livermore Lord Darling of Roulanish Lord Sharkey Lord Forsyth of Drumlean Lord Tugendhat Lord Hollick (Chairman) Lord Turnbull Lord Kerr of Kinlochard Baroness Wheatcroft Lord Lamont of Lerwick Declaration of interests See Appendix 1. A full list of Members’ interests can be found in the Register of Lords’ Interests: http://www.parliament.uk/mps-lords-and-offices/standards-and-interests/register-of-lords- interests Publications All publications of the Committee are available at: http://www.parliament.uk/hleconomicaffairs Parliament Live Live coverage of debates and public sessions of the Committee’s meetings are available at: http://www.parliamentlive.tv Further information Further information about the House of Lords and its Committees, including guidance to witnesses, details of current inquiries and forthcoming meetings is available at: http://www.parliament.uk/business/lords Committee staff The staff who worked on this inquiry were Ayeesha Waller (Clerk), Ben McNamee (Policy Analyst), Oswin Taylor (Committee Assistant) and Dr Aaron Goater and Dr Jonathan Wentworth of the Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology. Contact details All correspondence should be addressed to the Clerk of the Economic Affairs Committee, Committee Office, House of Lords, London SW1A 0PW. -

How Smart Metering and Smart Charging May Help a Local Energy Community in Collective Self-Consumption in Presence of Electric Vehicles

energies Article How Smart Metering and Smart Charging may Help a Local Energy Community in Collective Self-Consumption in Presence of Electric Vehicles Giuseppe Barone 1 , Giovanni Brusco 1 , Daniele Menniti 1 , Anna Pinnarelli 1 , Gaetano Polizzi 1, Nicola Sorrentino 1, Pasquale Vizza 1 and Alessandro Burgio 2,* 1 Department of Mechanical, Energy and Management Engineering, University of Calabria, 87036 Rende, Italy; [email protected] (G.B.); [email protected] (G.B.); [email protected] (D.M.); [email protected] (A.P.); [email protected] (G.P.); [email protected] (N.S.); [email protected] (P.V.) 2 Independent Researcher, 87036 Rende, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 11 July 2020; Accepted: 4 August 2020; Published: 12 August 2020 Abstract: The 2018/2001/EU renewable energy directive (RED II) underlined the strategic role of energy communities in the EU transition process towards sustainable and renewable energy. In line with the path traced by RED II, this paper proposes a solution that may help local energy communities in increasing self-consumption. The proposed solution is based on the combination of smart metering and smart charging. A set of smart meters returns the profile of each member of the community with a time resolution of 5 s; the aggregator calculates the community profile and regulates the charging of electric vehicles accordingly. An experimental test is performed on a local community composed of four users, where the first is a consumer with a Nissan Leaf, whereas the remaining three users are prosumers with a photovoltaic generator mounted on the roof of their home. -

Italy's Effort to Phase out and Rationalise Its Fossil Fuel Subsidies

ITALY’S EFFORT TO PHASE OUT AND RATIONALISE ITS FOSSIL-FUEL SUBSIDIES A REPORT ON THE G20 PEER-REVIEW OF INEFFICIENT FOSSIL-FUEL SUBSIDIES THAT ENCOURAGE WASTEFUL CONSUMPTION IN ITALY PREPARED BY THE MEMBERS OF THE PEER-REVIEW TEAM: ARGENTINA, CANADA, CHILE, CHINA, FRANCE, GERMANY, INDONESIA, NETHERLANDS, NEW ZEALAND, IEA, UN ENVIRONMENT, IISD, EUROPEAN ENERGY RETAILERS, GREEN BUDGET EUROPE, THE OECD (CHAIR OF THE PEER-REVIEW) AND SELECTED EXPERTS APRIL 2019 1 │ Italy’s effort to phase out and rationalise its fossil-fuel subsidies A report on the G20 peer-review of inefficient fossil-fuel subsidies that encourage wasteful consumption in Italy Prepared by the members of the peer-review team: Argentina, Canada, Chile, China, France, Germany, Indonesia, Netherlands, New Zealand, IEA, UN Environment, IISD, European Energy Retailers, Green Budget Europe, the OECD (Chair of the peer-review) and selected experts ITALY’S EFFORT TO PHASE OUT AND RATIONALISE ITS FOSSIL FUEL SUBSIDIES 2 │ Table of contents Acronyms and Abbreviations ............................................................................................................... 4 Executive Summary .............................................................................................................................. 5 1. Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 7 1.1. Background and context .............................................................................................................. -

Propane & Net Zero

PROPANE & NET ZERO WHY NET ZERO IS IMPORTANT “Net zero” refers to achieving an overall balance between emissions produced and emissions taken out of the atmosphere. Propane can help reduce CO2 emissions by replacing heavy carbons like coal, oil and even wood. Its affordability also ensures every consumer can share equitably in the benefits propane brings. PROPANE DECARBONIZES PROPANE ENSURES EQUITY Clean and renewable energy like propane Access to clean, affordable and renewable energy accelerates decarbonization. like propane ensures equity on the path to zero. Δ Decarbonization requires more cleaner energy options. The Δ Urban and rural low-income households, especially U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Office of Scientific and African American and Latinx households, spend roughly Technical Information says that large emissions reductions three times as much of their income on energy costs are achievable through a broad range of opportunities, as non-low-income households. In February 2021, EIA including the use of low- or zero-carbon alternatives. reported that electricity was 68% more expensive per million BTUs than propane. Δ The electric grid isn’t always the cleanest answer. Currently, propane-fueled medium- and heavy-duty Δ Energy should be affordable, so that no one has to vehicles provide a lower carbon footprint solution in 38 go without, but the share of income that low-income U.S. states when compared to medium- and heavy-duty households spent on electricity rose by 1/3 in the last EVs charged from the electrical grid. decade. Δ Propane is innovating everyday. It is, in fact, the new Δ Everyone should have access to clean energy and home diesel. -

An Overview of Behind-The-Meter Solar-Plus-Storage

AN OVERVIEW OF BEHIND-THE- METER SOLAR-PLUS-STORAGE REGULATORY DESIGN Approaches and Case Studies to Inform International Applications Owen Zinaman, Thomas Bowen, and Alexandra Aznar National Renewable Energy Laboratory March 2020 A product of the USAID-NREL partnership Contract No. IAG-17-2050 NOTICE This work was authored, in part, by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), operated by Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC, for the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) under Contract No. DE- AC36-08GO28308. Funding provided by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) under Contract No. IAG-17-2050. The views expressed in this report do not necessarily represent the views of the DOE or the U.S. Government, or any agency thereof, including USAID. This report is available at no cost from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) at www.nrel.gov/publications. U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) reports produced after 1991 and a growing number of pre-1991 documents are available free via www.OSTI.gov. Cover photo from iStock 471670114. NREL prints on paper that contains recycled content. Acknowledgments The authors thank Anurag Mishra and Sarah Lawson from the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) Office of Energy and Infrastructure for their support of this work. We also wish to thank the following individuals for their detailed review comments, insights, and contributions to this report (names listed alphabetically by organization and last name). Clean Energy Group—Seth Mullendore E3 Analytics—Toby -

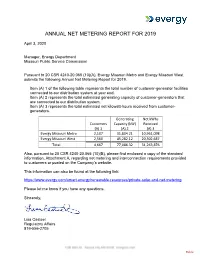

Annual Net Metering Report for 2019

ANNUAL NET METERING REPORT FOR 2019 April 3, 2020 Manager, Energy Department Missouri Public Service Commission Pursuant to 20 CSR 4240-20.065 (10)(A), Evergy Missouri Metro and Evergy Missouri West submits the following Annual Net Metering Report for 2019. Item (A) 1 of the following table represents the total number of customer-generator facilities connected to our distribution system at year end. Item (A) 2 represents the total estimated generating capacity of customer-generators that are connected to our distribution system. Item (A) 3 represents the total estimated net kilowatt-hours received from customer- generators. Generating Net kWhs Customers Capacity (kW) Received (A) 1 (A) 2 (A) 3 Evergy Missouri Metro 2,107 31,804.21 10,961,098 Evergy Missouri West 2,560 45,282.12 20,302,687 Total 4,667 77,086.32 31,263,876 Also, pursuant to 20 CSR 4240-20.065 (10)(B), please find enclosed a copy of the standard information, Attachment A, regarding net metering and interconnection requirements provided to customers or posted on the Company’s website. This information can also be found at the following link: https://www.evergy.com/smart-energy/renewable-resources/private-solar-and-net-metering Please let me know if you have any questions. Sincerely, Lisa Casteel Regulatory Affairs 816-556-2705 Public Attachment A Public FILED Missouri Public Service Commission EE-2019-0056; JE-2019-0028 FILED Missouri Public Service Commission EE-2019-0056; JE-2019-0028 FILED Missouri Public Service Commission EE-2019-0056; JE-2019-0028 KCP&L GREATER MISSOURI OPERATIONS COMPANY P.S.C. -

Department of Energy & Climate Change Short Guide

A Short Guide to the Department of Energy & Climate Change July 2015 Overview Decarbonisation Ensuring security Affordability Legacy issues of supply | About this guide This Short Guide summarises what the | Contact details Department of Energy & Climate Change does, how much it costs, recent and planned changes and what to look out for across its main business areas and services. If you would like to know more about the NAO’s work on the DECC, please contact: Michael Kell Director, DECC VfM and environmental sustainability [email protected] 020 7798 7675 If you are interested in the NAO’s work and support The National Audit Office scrutinises public spending for Parliament and is independent of government. The Comptroller and Auditor General for Parliament more widely, please contact: (C&AG), Sir Amyas Morse KCB, is an Officer of the House of Commons and leads the NAO, which employs some 810 people. The C&AG Adrian Jenner certifies the accounts of all government departments and many other Director of Parliamentary Relations public sector bodies. He has statutory authority to examine and report [email protected] to Parliament on whether departments and the bodies they fund have used their resources efficiently, effectively, and with economy. Our 020 7798 7461 studies evaluate the value for money of public spending, nationally and locally. Our recommendations and reports on good practice For full iPad interactivity, please view this PDF help government improve public services, and our work led to Interactive in iBooks or GoodReader audited savings of £1.15 billion in 2014. -

Corporate Responsibility Report 2003 What Matters to You

Centrica ‘We aim to build positive relationships by developing a sustainable approach to doing business.’ Sir Roy Gardner, Chief Executive Corporate Responsibility Report 2003 What matters to you... Our first responsibility is to meet our customers’ needs for essential services. Through our business activities, we are an integral part of local communities. We create wealth for employees, generate taxes to government, create jobs among suppliers and deliver a fair reward to investors who finance our business. Centrica Energy manages Centrica Business Services One.Tel provides a fresh In Canada, Direct Energy our gas production and aims to be recognised as the and innovative approach in Essential Home Services offers electricity generation most innovative and flexible providing a range of landline, gas and electricity and a range capabilities, along with provider of energy and other mobile and internet services of home services in Ontario. third party supply and essential services to the UK across the UK. In Texas, we supply electricity transportation contracts. business community. under the Direct Energy, WTU Retail Energy and CPL Retail Energy brands to homes and businesses. We supply gas under the British Gas is the market The AA provides reassurance Luminus, our joint venture Energy America brand in leader in delivering gas, and services to motorists energy business in Belgium, Michigan, Ohio and electricity and telecoms to in the UK and Ireland. Our and Luseo Energia, our Pennsylvania. Direct Energy millions of homes across roadside assistance remains business to business brand Business Services provides the UK. As well as energy at the core of our activities in Spain, provide us with a comprehensive energy and telecoms, we offer and we are the UK’s number launch pad into the markets solutions to businesses customers an increasing one insurance intermediary.