Teaching Hands-Only CPR in Schools: a Program Evaluation in San José, Costa Rica

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ZONA DE CONSERVACIÓN VIAL 1-3 LOS SANTOS Conavi MAPA DE

(! 22 480000 ¤£2 (! UV306 ¤£ (! O R T S I 1 1512 I O R 6 1 IQU LE V IO BRASIL SANTA ANA 2 0 SAN PEDRO H I 10 0 ! C O R V 0 102 1 ( IO C I IR 105 1 R L S 2 R L IL 121 2 8 L 0 A A 0 RIO T A A 167 10104 0 ¬ 0 1 L ¬ « « SAN RAFAEL 1 221 1 FRESES E 177 176 «¬ U 39 0 «¬ 202 7 219 R I ¤£ «¬ «¬ 1 1 ¬ 1 « ¬ C 2 CONCEPCIÓN « 0 39 O 0 I 1 1 £ ¤£ R 22 121 1 ¤ ¤£ 0 215 «¬ 1 «¬ DULCE NOMBRE 1 PASQUÍ 0 CURRIDABAT ESCAZÚ 177 ZAPOTE 8 1 311 «¬ 209 1 UV (! 110 «¬ Q POTRERO CERRADO U BELLO HORIZONTE «¬ 215 E B (! R 176 «¬ A HATILLO D O TIERRA BLANCA A ¬ R O MARIA « I CURRIDABAT 401 A D COLÓN 1 GUI H 1 LA 204 A UV O 0 R ZONA DE CONSERVACIÓN VIAL 1-3 0 214 T N 1 ! ZONA DE CONSERVACIÓ(! N VIAL 1-3 «¬ ( N D «¬ E PIEDRAS NEGRAS A V 136 SAN SEBASTIÁN 11802 E «¬ 211 SAN FRANCISCO R 252 251 218 IO 39 «¬ «¬ «¬ «¬ R I £ IB 210 ¤ TRES RÍOS BANDERILLA 175 R 1 T I ¬ 2 0 « conavi 0 1 conavi SAN FELIPE 19 ¬ 1011 IO « 4 LOS SANTOS 3 LOMAS DE AYARCO PICAGRES LOS SANTOS 211 R (! SAN ANTONIO TIRRASES 213 ¬ 0 110 207 « 3 «¬ ALAJUELITA «¬ «¬ FIERRO BEBEDERO 409 RIO UV PACAC UA (! SAN DIEGO 2 402 R I £ UV O 105 213 ¤ OR «¬ LLANO LEÓN O «¬ 105 SAN ANTONIO «¬ DESAMPARADOS SAN VICENTE ORATORIO R UASI-2019-11-013 / Actualizado a Febrero 2019 IO 210 (! D 219 214 1 A «¬ CALLE FALLAS 03 M «¬ COT PABELLÓN R «¬ 0 A S 4 I O CONCEPCIÓN R A SAN JOSECITO IO G RÍO AZUL U R R E U VILLA NUEVA C S A OCHOMOGO 230 1 0 «¬ 3 409 0 UV 1 PASO ANCHO QUEBRADA GRANDE QUEBRADA HONDA 217 214 PATARRÁ CARTAGO O 239 D «¬ «¬ «¬ A T 209 N E «¬ V RI SAN JUAN DE DIOS E 3 DESAMPARADITOS O J R 0 AR 7 IS IO 0 219 -

2018-19 District 4240 Global Grant Initiative

2018-19 DISTRICT 4240 GLOBAL GRANT INITIATIVE “TIRRASES COMMUNITY DENTAL CLINIC” “DISEASE PREVENTION AND TREATMENT” “ECONOMIC AND COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT” “MATERNAL AND CHILD HEALTH” 2nd Draft-2018-19 Costa Rica GG-1571 GLOBAL GRANT- TIRRASES COMMUNITY DENTAL CLINIC REGION: CENTRAL AMERICA | COUNTRY: COSTA RICA | LOCATION: TIRRASES, CURRIDABAT, SAN JOSE. ROTARY AREAS OF FOCUS: DISEASE PREVENTION AND TREATMENT | ECONOMIC AND COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT | MATERNAL AND CHILD HEALTH (and ADULT & ELDERLY DENTAL HEALTH). ROTARY HOST PARTNERS: SAN PEDRO CURRIDABAT ROTARY CLUB - DISTRICT 4240 COSTA RICA. PARTNERING CLUBS AND OTHER ENTITIES: LEWISVILLE MORNING ROTARY CLUB, DENTON NOON ROTARY CLUB - DISTRICT 5790 TEXAS, SOUTHWEST AIRLINES, ROTARACTS AND INTERACTS, FUNDACION CURRIDABAT, AWOW INTERNATIONAL GIRLS LEADERSHIP INITIATIVE, CLINICA DENTAL LOMA VERDE, MUNICIPALITY GOVERNMENT OF CURRIDABAT, CAMPBELL & WILLIAMS FAMILY, DENTAL OF HIGHLAND VILLAGE -TX, MEHARRY MEDICAL COLLEGE, AND FISK UNIVERSITY, NASHVILLE TN. PLANNING COUNCIL (PC)- SAN PEDRO CURRIDABAT ROTARY CLUB - DISTRICT 4240 COSTA RICA, LEWISVILLE MORNING ROTARY CLUB, DENTON NOON ROTARY CLUB - DISTRICT 5790 TEXAS, SOUTHWEST AIRLINES, MEHARRY SCHOOL OF DENTISTRY, CAMPBELL & WILLIAMS DENTAL FOUNDATION, CLINICA DENTAL LOMA VERDE, SIGNED BY DRA. AYLIN SANCHEZ, FACULTY OF DENTISTRY UCR SIGNED BY DR. RONALD DE LA CRUZ, DR. ANDRES DE LA CRUZ “ORTHODONTICS” JEFFREY SIEBERT. DDS PC: WILL HOST A SERIES OF CONFERENCE CALLS AND PLANNING MEETINGS WITH MEMBERS OF DISTRICT 5790, DISTRICT 4240, STUDENT RESIDENTS, UNIVERSITY FACULTY, AND DENTAL PROFESSIONAL. SERVICE PROJECT VISIT: BY ROTARIANS, INTERACT, ROTARACT, COMMUNITY LEADERS, AND VOLUNTEERS. SOUTHWEST AIRLINES: PROVIDE AIRLINE TICKETS AND CARGO SPACE FOR THE EQUIPMENT. OVERVIEW: IN THE FALL OF 2017 A NEED ASSESSMENT WAS COMPLETED. AND AS A RESULT, A PILOT PROJECT WAS LAUNCHED. -

CENTROS DE ACOPIO DE MATERIAL RECICLABLE.Pdf

CENTROS DE ACOPIO DE MATERIAL RECICLABLE Recopilado por: Xinia Hernández Montero PAPEL PERIODICO persona Cantidad Condiciones de presentación y Empresa contácto Teléfono Dirección exacta Precio de compra Minima entrega Paso Ancho, Carretera a Desamparados, 100 mts. Sur y 75 suroeste de antigua Los desechos deben de venir sin Bodega de Envases El Pastor Radio Reloj. San ¢ 7 (Kilo),Los mezclar con otros metales y Tiribí Valverde 2-2272942 José directorios a ¢ 10. No Hay entregados en el centro de acopio 100m sur de la antigua entrada del El precio varia de la calidad del Florentino Colegio Saint Clare ¢ 17 (Kilo), papel producto incluyendo si está revuelto Bodega Florentino Umaña Umaña 2-2352172 (Moravia) periódico ¢30 - ¢32. No Hay o no. 900 sur y 100 oeste Limpio y seco, mejor si está Centro de Reciclaje Planeta Jaime de la iglesia Católica amarrado, se recoge después de 300 Limpio Córdoba 2892-9601 de Escazú ¢ 5 (Kilo) No Hay Kilos 50 al este del Aserradero Tres M, María Teresa 445-4658 / San Juan (San COFERENE Arguedas 447-2181 Ramón) ¢ 15 (Kilo) No Hay Sin Contaminar y seleccionado. 2-298- Limpio , sin revolver y Kimberly Clark Geovanny 3115/2- La Rivera de Belén, Trabaja con Grupos contaminantes , se debe dejar en las Centroamerica S.A Mena 29831100 calle la Scott inscriptos mayoristas. No Hay instalaciones. ¢ 29 , en centro Cartago de la educativos, como Plycem Construsistemas de Basílica de los parte del manejo de Costa Rica S.A. (antes Ángeles, 5km, desechos y solución El periódico tiene que estar AMANCO) Sandra Brenes 25510866 carretera a Paraíso. -

Nombre Del Comercio Provincia Distrito Dirección Horario

Nombre del Provincia Distrito Dirección Horario comercio Almacén Agrícola Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, Cruce Del L-S 7:00am a 6:00 pm Aguas Claras Higuerón Camino A Rio Negro Comercial El Globo Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, contiguo L - S de 8:00 a.m. a 8:00 al Banco Nacional p.m. Librería Fox Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, frente al L - D de 7:00 a.m. a 8:00 Liceo Aguas Claras p.m. Librería Valverde Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala, Aguas Claras, 500 norte L-D de 7:00 am-8:30 pm de la Escuela Porfirio Ruiz Navarro Minisúper Asecabri Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, Las Brisas L - S de 7:00 a.m. a 6:00 400mts este del templo católico p.m. Minisúper Los Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala, Aguas Claras, Cuatro L-D de 6 am-8 pm Amigos Bocas diagonal a la Escuela Puro Verde Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, Porvenir L - D de 7:00 a.m. a 8:00 Supermercado 100mts sur del liceo rural El Porvenir p.m. (Upala) Súper Coco Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala, Aguas Claras, 300 mts L - S de 7:00 a.m. a 7:00 norte del Bar Atlántico p.m. MINISUPER RIO Alajuela AGUAS ALAJUELA, UPALA , AGUAS CLARAS, L-S DE 7:00AM A 5:00 PM NIÑO CLARAS CUATRO BOCAS 200M ESTE EL LICEO Abastecedor El Alajuela Aguas Zarcas Alajuela, Aguas Zarcas, 25mts norte del L - D de 8:00 a.m. -

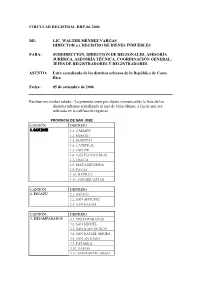

Circular Registral Drp-06-2006

CIRCULAR REGISTRAL DRP-06-2006 DE: LIC. WALTER MÉNDEZ VARGAS DIRECTOR a.i. REGISTRO DE BIENES INMUEBLES PARA: SUBDIRECCIÓN, DIRECCIÓN DE REGIONALES, ASESORÍA JURÍDICA, ASEOSRÍA TÉCNICA, COORDINACIÓN GENERAL, JEFES DE REGISTRADORES Y REGISTRADORES. ASUNTO: Lista actualizada de los distritos urbanos de la República de Costa Rica Fecha: 05 de setiembre de 2006 Reciban mi cordial saludo. La presente tiene por objeto comunicarles la lista de los distritos urbanos actualizada al mes de Julio último, a fin de que sea utilizada en la califiación registral. PROVINCIA DE SAN JOSE CANTÓN DISTRITO 1. SAN JOSE 1.1. CARMEN 1.2. MERCED 1.3. HOSPITAL 1.4. CATEDRAL 1.5. ZAPOTE 1.6. SAN FCO DOS RIOS 1.7. URUCA 1.8. MATA REDONDA 1.9. PAVAS 1.10. HATILLO 1.11. SAN SEBASTIAN CANTÓN DISTRITO 2. ESCAZU 2.1. ESCAZU 2.2. SAN ANTONIO 2.3. SAN RAFAEL CANTÓN DISTRITO 3. DESAMPARADOS 3.1. DESAMPARADOS 3.2. SAN MIGUEL 3.3. SAN JUAN DE DIOS 3.4. SAN RAFAEL ARRIBA 3.5. SAN ANTONIO 3.7. PATARRA 3.10. DAMAS 3.11. SAN RAFAEL ABAJO 3.12. GRAVILIAS CANTÓN DISTRITO 4. PURISCAL 4.1. SANTIAGO CANTÓN DISTRITO 5. TARRAZU 5.1. SAN MARCOS CANTÓN DISTRITO 6. ASERRI 6.1. ASERRI 6.2. TARBACA (PRAGA) 6.3. VUELTA JORCO 6.4. SAN GABRIEL 6.5.LEGUA 6.6. MONTERREY CANTÓN DISTRITO 7. MORA 7.1 COLON CANTÓN DISTRITO 8. GOICOECHEA 8.1.GUADALUPE 8.2. SAN FRANCISCO 8.3. CALLE BLANCOS 8.4. MATA PLATANO 8.5. IPIS 8.6. RANCHO REDONDO CANTÓN DISTRITO 9. -

Listado De Centros Educativos Donde No Se Impartirán Lecciones Del 16 Al

Listado de centros educativos donde no se impartirán lecciones Del 16 al 29 de marzo del 2020 Según resoluciones MEP-0530-2020 y MEP-0531-2020 Actualizado el domingo 15 de marzo de 2020 a las 2:55 p.m. # Provincia Cantón Distrito Dirección Regional Circuito Nombre del Centro Educativo Código 1 Alajuela Alajuela Alajuela DRE Alajuela 1 ENSEÑANZA ESPECIAL Y REHABILITACION ALAJUELA 4439 2 Alajuela Grecia Grecia DRE Alajuela 6 ENSEÑANZA ESPECIAL DE GRECIA 4440 3 Alajuela San Carlos Quesada DRE San Carlos 14 ENSEÑANZA ESPECIAL AMANDA ALVAREZ DE UGALDE 4514 4 Alajuela San Ramón San Ramón DRE Occidente 1 ENSEÑANZA ESPECIAL Y REHABILITACION DE SAN RAMÓN 4495 5 Cartago Cartago Carmen DRE Cartago 1 DR CARLOS SAENZ HERRERA 4535 6 Cartago La Unión Río Azul DRE Desamparados 1 FRANCISCO GAMBOA MORA 548 7 Cartago La Unión Río Azul DRE Desamparados 1 LINDA VISTA 476 8 Cartago La Unión San Diego DRE Cartago 6 CALLE GIRALES 1917 9 Cartago La Unión San Diego DRE Cartago 6 CALLE MESÉN 1726 10 Cartago La Unión San Diego DRE Cartago 6 LICEO SAN DIEGO 4059 11 Cartago La Unión San Diego DRE Cartago 6 SAN DIEGO 1871 12 Cartago La Unión San Diego DRE Cartago 6 SANTIAGO DEL MONTE 1900 13 Cartago La Unión San Diego DRE Cartago 6 UNIDAD PEDAGÓGICA SAN DIEGO 5834 14 Cartago La Unión San Juan DRE Cartago 6 MARÍA AMELIA MONTEALEGRE 1880 15 Cartago La Unión San Juan DRE Cartago 6 VILLAS DE AYARCO 1728 16 Cartago La Unión San Rafael DRE Cartago 6 CAROLINA BELLELLI DE M. -

M Emoria I Nstitucional 2 0

M e m o r i a I n s t i t u c i o n a l 2 0 0 6 M e m o r i a I n s t i t u c i o n a l CCSS 2 0 0 6 Índice Presentación 5 Aspectos generales 7 • Introducción 8 • Cobertura 9 • Prestaciones en dinero 13 • Ingresos y gastos 14 • Imagen de la Institución 22 Capítulo I Estructura Organizacional 24 • Introducción 25 • Miembros de Junta Directiva 26 • Miembros de la Administración Superior 28 • Misión y Visión Institucional 30 • Organigrama institucional 31 • Regionalización de Establecimientos de Salud, mapa 33 • Hospitales Nacionales, Especializados. Regionales y Periféricos 34 • Áreas de Salud y EBAIS, por Región Programática, a diciembre del 2006 35 • Regionalización de Sucursales, mapa 52 • Listado actualizado a diciembre del 2006 por región de las Sucursales y Agencias. 53 Capítulo II Servicios en cada región del país. Gerencia Médica 54 • Introducción 55 • Nuestra producción en salud 55 • Información general 68 • Capacitación 74 • Las personas: Eje de nuestra atención 78 Capítulo III Solidaridad: principio fundamental de nuestro Sistema de Pensiones 80 • Introducción 81 • Aplicación de la reforma al Reglamento del Seguro de Invalidez, Vejez y Muerte 81 • Mejora en la gestión de beneficios del Seguro IVM 82 • Régimen No Contributivo de Pensiones. Aumento solidario para quienes menos tienen 84 • Inversiones del Seguro IVM: se incrementan los rendimientos 85 • Resultados en la colocación de créditos hipotecarios 88 • Prestaciones Sociales 90 3 M e m o r i a I n s t i t u c i o n a l CCSS 2 0 0 6 Capítulo IV Impacto en morosidad y recaudación. -

Mapa Del Cantón Curridabat 18, Distrito 01 a 03

MAPA DE VALORES DE TERRENOS POR ZONAS HOMOGÉNEAS PROVINCIA 1 SAN JOSÉ CANTÓN 18 CURRIDABAT 531200 532000 532800 533600 534400 535200 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! MINISTERIO DE HACIENDA ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE TRIBUTACIÓN ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! A ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! S ! a ! ! n ! ! ! DIVISIÓN ! ! ! R ! ! a ! ! ! ! ! ! ! f ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! a ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! e ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ÓRGANO DE NORMALIZACIÓN TÉCNICA ! ! l ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 213600 ! ! ! 213600 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Parque ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Facilidades ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Comunales ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 118-02-U12 ! ! Urbanización 118-02-U12 ! ! ! Urbanización ! ! Urb. ! ! ! ! Catalán ! ! ! Europa ! ! Alamos ! ! Cond. El ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Bosque ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 118-02-U11 ! 118-02-U11 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Facilidades ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Comunales! Quebrada Norte ! ! -

Solar-Powered Dental Clinic” That Is Mobilizing Skilled Rotarians, Rotaractors, and Interactors, to Be Part of the Rotary Theme This Year

“Service Above Self – Community Dental Project” In 2017 AWOW hosted a dental pilot project for the community of Tirrases. The goals of the project are to encourage the development of innovative practices in oral health care while providing care to populations with high disease rates and the least access to dental care. Dentists, members of Lewisville Morning Rotary (LMRC), and volunteers from North Texas traveled to Costa Rica courtesy of Southwest Airlines ®. They assisted in the dental project alongside Rotary Club San Pedro-Curridabat and La Cometa. “Service Above Self – Community Dental Project” LMRC members (President DDS. Jeff Siebert, Immediate Past President Carolyn Wright, and Rtn. Frances Al-Waely) participated in the project with members of Club Rotario San Pedro-Curridabat (Rtn. DDS. Aylin Sanchez-Campos, Rtn. Fernando and Ileana Teran), and volunteers of La Cometa Community Center to serve the children of Tirrases. INSPIRE District 5790 - Lewisville Morning Rotary Club, Lewisville, Texas, USA and District 4240 - Club Rotario de San Pedro- Curridabat, San Jose, Costa Rica want to share with you an exciting Global Grant opportunity for you and your club members to travel to Costa Rica and participate in the dental project. IMPACT Located in Costa Rica, Tirrases is a marginalized urban community that was formed as a community some 20 years ago, without any urban planning and under the shadow of the city’s garbage landfill of Rio Azul, with a population of +20,000 inhabitants, of which 35% are under 20 years of age from very low-income families living in ramshackle environments. The residents of this community have minimum access if any at all to dental care and oral hygiene education. -

Bono Comunal Mejora Infraestructura En 19 Comunidades Del País

Bono Comunal mejora infraestructura en 19 comunidades del país Mejoras en Ciudadela La Europa, en Granadilla de Curridabat , es el más reciente proyecto de este tipo aprobado por el BANHVI Con la aprobación del mejoramiento de obras de infraestructura en Ciudadela La Europa, en Granadilla de Curridabat, ya son 19 las comunidades beneficiadas con los recursos del Bono Comunal, el cual es administrado por el Banco Hipotecario de la Vivienda (BANHVI), desde el año 2008 cuando se inició con este programa. En 13 de los 19 proyectos señalados, los trabajos de mejoramiento urbano ya fueron concluidos y 13.121 familias disfrutan de un mejor entorno. Los 6 restantes cuentan con financiamiento aprobado, o los trabajos están en marcha. Otras cuatro localidades más tienen proyectos en fase de estudio o prefactibilidad. Las obras típicas desarrolladas en los proyectos financiados con el Bono Comunal son: a) Sistema de abastecimiento de agua potable y colocación de hidrantes. b) Conducción y/o tratamiento de aguas residuales. c) Sistema de evacuación de aguas pluviales. d) Vías públicas con su respectiva señalización vial horizontal y vertical. e) Construcción de aceras con rampas para personas con discapacidad. f) Habilitación de parques, áreas de juegos infantiles y espacios comunales. g) Mejoras en tendido eléctrico y alumbrado público. En el cantón de Desamparados, San José, se han finalizado cuatro de los 13 proyectos de Bono Comunal: Los Guido Sector 1; Las Victorias; La Capri y Las Mandarinas, con los cuales se benefició a 6.091 familias y la inversión fue de 4.450 millones. Otros proyectos son Ciudadela 25 de Julio (Hatillo) en beneficio de 250 familias; La Angosta (146 familias) y El Futuro (254 familias) ambos en Alajuela; Las Gaviotas (121 familias) en La Suiza de Turrialba y los proyectos Venecia y El Verolís, en Barranca de Puntarenas. -

Encuesta Hogares.Pdf

Preparado para: Edgar Mora Alcalde Municipalidad de Curridabat Diagnóstico del Cantón de Curridabat Metodología Trabajo de campo: Margen de error de 2.8 pp al 95% del 16 al 29 de de confianza a Tamaño de febrero del 2012 nivel de la muestra muestra: Población de 1201 total, considerando entrevistas en factor de 1 equipo de 10 interés: Cantón hogares del corrección por encuestadores y 2 de Curridabat cantón poblaciones finitas. supervisor. Descripción de la Muestra n=1.201 Descripción de la Muestra Distrito Edad de Jefatura Sánchez 18 a 29 8% 7% 30 a 39 60 o Más 13% Granadilla Curridabat 37% 23% 44% 40 a 49 20% Tirrases 50 a 59 25% 23% Educación Jefatura Jefatura Femenina Primaria Universida 35% Si d 34% 36% No 66% Secundaria 29% n=1.201 Descripción de la Muestra Menores en Casa Adultos Mayores Si Si 33% 44% No 56% No 67% Personas con Discapacidad Adolecentes con Hijos Si Si 1% 19% No No 81% 99% Demografía del Hogar n=4.400 Distribución de Género Total 4.400 1.864 1.066 310 1.160 1.288 2.511 1.330 843 50% 53% 53% 53% 57% 54% 54% 53% 63% 50% 48% 47% 47% 43% 46% 46% 47% 37% Índice Masculinidad Total Curridabat Granadilla Sánchez Tirrases Jefatura Con Adultos Personas Femenina Menores de Mayores con Edad Discapacidad 90.5 88.7 89.7 75.1 99.0 59.2 85.9 84.7 89.4 Índice de Masculinidad: es el número de hombres dividido por el número de mujeres en el hogar. -

Provincia Nombre Provincia Cantón Nombre Cantón Distrito Nombre

Provincia Nombre Provincia Cantón Nombre Cantón Distrito Nombre Distrito Barrio Nombre Barrio 1 San José 1 San José 1 CARMEN 1 Amón 1 San José 1 San José 1 CARMEN 2 Aranjuez 1 San José 1 San José 1 CARMEN 3 California (parte) 1 San José 1 San José 1 CARMEN 4 Carmen 1 San José 1 San José 1 CARMEN 5 Empalme 1 San José 1 San José 1 CARMEN 6 Escalante 1 San José 1 San José 1 CARMEN 7 Otoya. 1 San José 1 San José 2 MERCED 1 Bajos de la Unión 1 San José 1 San José 2 MERCED 2 Claret 1 San José 1 San José 2 MERCED 3 Cocacola 1 San José 1 San José 2 MERCED 4 Iglesias Flores 1 San José 1 San José 2 MERCED 5 Mantica 1 San José 1 San José 2 MERCED 6 México 1 San José 1 San José 2 MERCED 7 Paso de la Vaca 1 San José 1 San José 2 MERCED 8 Pitahaya. 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 1 Almendares 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 2 Ángeles 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 3 Bolívar 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 4 Carit 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 5 Colón (parte) 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 6 Corazón de Jesús 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 7 Cristo Rey 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 8 Cuba 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 9 Dolorosa (parte) 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 10 Merced 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 11 Pacífico (parte) 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 12 Pinos 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 13 Salubridad 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 14 San Bosco 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 15 San Francisco 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 16 Santa Lucía 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 17 Silos.