Takitimu Forestry Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Zealand Gazette

1025 "r THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE. WELLINGTON, THURSDAY, APRIL 9, 1925. RRATUM.-In the Order in Counoil dated the 19th day I Additional Land taken for the Kawalcawa-Hokianga Railway E of January, 1920, and published in the New Zealand (Okaihau Bectinn) and for Road·diversions in connection Gazette No.4, page 161, of the 23rd day of January, 1925, therewith. declaring portion of Glenora Road, in the Akitio County, to be a county TOad, read "oounty road" in lieu of " Govern· ment road" in the ninth line of the said Order in Council. [L.S.) CHARLES FERGUSSON, Governor.General. A PROCLAMATION. N pursuance and exercise of the powers and authorities Ot"OW1t. Land Bet 68ide a8 a. ProviBional State ForeBt. I vested in me by the Public Works Act, 1908, and of every other power and authority in anywise enabling me in [L.S.] CHARLES FERGUSSON, Governor·Generai. this behalf, I, General Sir Charles Fergusson, Baronet, Go. A PROCLAMaTION. vernor·General of the Dominion of New Zealand, do hereby proclaim and deolare that the additional land mentioned in the B-y virtue and in exeroise of the powers and authorities Schedule hereto is hereby taken for the Kawakawa-Hokianga conferred upon me by scotion eighteen of the Forests Railway (Okaihau Seotion) and for road· diversions in con· A~t, 1921-22, I, General Sir Charles Fergusson, Baronet, nection therewith. Governor·Generai of the Dominion of New Zealand, aoting by and with the advice and consent of the Executive Council of the said Dominion, do hereby set apart the Crowp. -

Proposed Gisborne Regional Freshwater Plan

Contents Part A: Introduction and Definitions Schedule 9: Aquifers in the Gisborne Region 161 Section 1: Introduction and How the Plan Works 3 Schedule 10: Culvert Construction Guidelines for Council Administered Drainage Areas 162 Section 2: Definitions 5 Schedule 11: Requirements of Farm Environment Plans 164 Part B: Regional Policy Statement for Freshwater Schedule 12: Bore Construction Requirements 166 Section 3: Regional Policy Statement For Freshwater 31 Schedule 13: Irrigation Management Plan Requirements 174 Part C: Regional Freshwater Plan Schedule 14: Clearances, Setbacks and Maximum Slope Gradients for Installation Section 4: Water Quantity and Allocation 42 of Disposal Systems 175 Section 5: Water Quality and Discharges to Water and Land 48 Schedule 15: Wastewater Flow Allowances 177 Section 6: Activities in the Beds of Rivers and Lakes 83 Schedule 16: Unreticulated Wasterwater Treatment, Storage and Disposal Systems 181 Section 7: Riparian Margins, Wetlands 100 Schedule 17: Wetland Management Plans 182 Part D: Regional Schedules Schedule 18: Requirements for AEE for Emergency Wastewater Overflows 183 Schedule 1: Aquatic Ecosystem Waterbodies 109 Schedule 19: Guidance for Resource Consent Applications 185 1 Schedule 2: Migrating and Spawning Habitats of Native Fish 124 Part E: Catchment Plans Proposed Schedule 3: Regionally Significant Wetlands 126 General Catchment Plans 190 Schedule 4: Outstanding Waterbodies 128 Waipaoa Catchment Plan 192 Gisborne Schedule 5: Significant Recreation Areas 130 Appendix - Maps for the Regional Freshwater Plan Schedule 6: Watercourses in Land Drainage Areas with Ecological Values 133 Regional Appendix - Maps for the Regional Freshwater Plan 218 Schedule 7: Protected Watercourses 134 Freshwater Schedule 8: Marine Areas of Coastal Significance as Defined in the Coastal Environment Plan 160 Plan Part A: Introduction and Definitions 2 Section 1: Introduction and How the Plan Works 1.0 Introduction and How the Plan Works Part A is comprised of the introduction, how the plan works and definitions. -

The Effect of Landuse and Geology on Macroinverterbate Communities in East Coast Streams, Gisborne, New Zealand

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. THE EFFECT OF LANDUSE AND GEOLOGY ON MACROINVERTERBATE COMMUNITIES IN EAST COAST STREAMS, GISBORNE, NEW ZEALAND. A stream draining exotic forestry flowing into pastoral land use, in soft geology, Gisborne, New Zealand. THE EFFECT OF LANDUSE AND GEOLOGY ON MACROINVERTERBATE COMMUNITIES IN EAST COAST STREAMS, GISBORNE, NEW ZEALAND. Harriet Roil Masters Thesis Massey University March 2020 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................... 4 General Introduction .................................................................................................................. 6 Chapter 1. ................................................................................................................................. 13 The interactive effects of geology and land use on East Coast macroinvertebrate stream communities. ........................................................................................................................ 13 Chapter 2. ................................................................................................................................. 42 The effect of forestry on stream macroinvertebrate communities in Gisborne, New Zealand ............................................................................................................................................. -

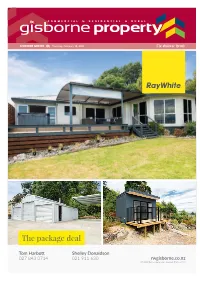

Property Guide, July 15, 2021

Thursday, July 15, 2021 2 3 4 5 71 CHALMERS ROAD TE HAPARA tender Closes: 12noon Wednesday 4th August 2021 the family favourite (unless sold prior) VIEWING: Sunday 11am – 11:30am 120m² 1323m² 3 2 Stop the search,call the bank, sort the Kiwisaver – I have found the home you’ve been waiting for. Whether it’s a super-sized section you’re after, the outlook over to the golf course, the close proximity to schools, or the hop, skip and a jump over to Rugby Park… families will absolutely love this one. Here’s all you want to know: • Built in the 1970’s – easy peasy insurance compliance right here; • Heat-pump, insulated ceilings and underfl oor; • Super spacious 120m2 in fl oorsize with generous living areas; • Modifi cation of the original garage makes for an awesome • Heaps of storage, all three bedrooms have inbuilt dressers and double wardrobes; outdoor he/she or teen cave (with w/c) or convert back; • Positioned perfectly to enjoy awesome afternoon sun; • The section – it’s a whopping 1323m2! Your winter pool project is just waiting here to be spruced up for the coming summer months. AND, being for sale by tender means conditional off ers are welcome – YAY for you. No waiting to move in either, with new plans locked and loaded, settlement date can be much sooner than later. P 06 929 1933 | M 027 553 5360 | E [email protected] | W www.tracyrealestate.co.nz 121 Ormond Road, Gisborne Tracy Bristowe, AREINZ | Licensed Real Estate Agent REA 2008 6 Te Karaka 10 Kipling Road Final Notice Time to change your pace? Thinking you need a change and want to be part of an awesome rural community? Are you trying to break into the housing Auction 3.00pm, Thu 22nd Jul, 2021, (unless sold prior), 66 Reads market or perhaps you are looking for something to get your teeth stuck into – well do I have the perfect property for you! Quay, Gisborne View Sat 17 Jul 12.00 - 12.30pm Located just a 20 minute drive from Gisborne you will find this 1000 sqm property. -

Property Guide, February 18, 2021

Thursday, February 18, 2021 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 108A ORMOND ROAD WHATAUPOKO a sunny gem 90m² 455m² 2+ 1 1 What a fabulous property, there is just so much to love about 108A Ormond Road, Whataupoko; there is something for everyone with this sweetie. LAST CHANCE • LOCATION: close to Ballance • JUST EASY: a pocket-size section that St Village with all the day to day packs a lot of punch. A manageable conveniences you may need – a super 455m2, with dual parking options given handy convenient location; the corner site. Nicely fenced, some • A LITTLE RETRO: a classic 1950s. Solid gardens in place, and fully fenced out structure, native timberwork and hardy back for your precious pets, or little weatherboard exterior. Good size ones; lounge, and kitchen/dining, and, both • EXTRAS: a shed for ‘tinkering’, and an bedrooms are double. Lovely as is, but outdoor studio for guests, hobbies, or with room to add value; maybe working from home? And Investors, if you are looking for a rock-solid property with IMPECCABLE tenants – get this one to the top of your list. tender Closes: 12pm Tuesday 23rd February 2021 (unless sold prior) VIEWING: Saturday 1pm-1:30pm Or call Tracy to view 70 ORMOND ROAD WHATAUPOKO it’s the location… 152m² 522m² 4 1+ 1 As a buyer you know it’s all about LOCATION & OPPORTUNITY, and they say “buy the worst house in the best street” to get ahead in the property game. LAST CHANCE To be fair, potentially not the ‘worst house’ but definitely one that piques the curiosity; and it’s located in a ‘best street’ a fabulous part of Gisborne – WHATAUPOKO. -

Schedule G15 : Aquatic Ecosystem Waterbodies

Schedule G15 : Aquatic Ecosystem Waterbodies Note: This Schedule was formerly Schedule 1 of the Regional Freshwater Plan. Schedule G15 contains a list of Aquatic Ecosystem Waterbodies. There are five parts to the Schedule. Schedule G15A contains the nationally and regionally significant habitats and migratory habits of native fish. The schedule identifies: the catchment the waterbody is within; the name of the river/stream or lake and/or stream tributary schedule and a list of the native fish that are known to use the waterbodies for habitat and migration. The schedule was developed based on the work undertaken under the RIVAS studies identifying nationally and regionally significant native fish habitat. Schedule G15B contains the additional key habitats for Long Finned Eel – a nationally threatened native species which the Gisborne region is recognised as providing a national stronghold for populations. The schedule identifies: the catchment the waterbody is within and the name of the river and/or stream tributary schedule where long finned eel populations are known to exist. Schedule G15C contains the freshwater habitats of threatened indigenous flora and fauna. The schedule identifies: the catchment the waterbody is within; the name of the river/stream or lake/wetland/river mouth and the threatened species present in the waterbody. Schedule G15D contains the known whitebait spawning sites in the region. The schedule contains the catchment, river or stream and location of the spawning site. Schedule G15E contains the important habitats of trout. The schedule contains the catchment, river or stream. It also outlines whether the stream is a nationally, regionally or locally significant habitat. -

G11 Schedule

Gisborne District Council Tairawhiti Resource Management Plan G11 Schedule TERRESTRIAL AREAS OF SIGNIFICANT CONSERVATION VALUE TABLE OF CONTENTS WP12 ........................................................................................................ 32 PR14 .......................................................................................................... 1 WR36 ........................................................................................................ 33 PR36 .......................................................................................................... 2 WR37 ........................................................................................................ 34 PR29 .......................................................................................................... 3 WR38 ........................................................................................................ 35 PR10 .......................................................................................................... 4 WR49 ........................................................................................................ 35 PP0 ............................................................................................................. 5 WR55 ........................................................................................................ 36 PR20 .......................................................................................................... 6 WR56 ....................................................................................................... -

Weekender, December 12, 2020

SATURDAY, DECEMBER 12, 2020 Of the canvas FULL CIRCLE: Lydia Monin, author of From In a corner of a Gisborne primary school playing ield is a tree planted early Poverty Bay to Broadway: The Story of Tom Heeney, and Tairawhiti Museum have last century in honour of former student, local hero and champion boxer, Tom combined their collections of memorabilia and material associated with early 20th Heeney. Lydia Monin, author of From Poverty Bay to Broadway: he Story century Gisborne boxer and local hero, Tom Heeney. of Tom Heeney, talks to Mark Peters about the signiicance of the Tairawhiti Picture by Paul Rickard Museum exhibition, Of the Canvas, a celebration of Tom Heeney. n aicionado of death in the Given Hemingway’s self-aggrandisement, made up of memorabilia, photographs, in the ring was his world heavyweight bullring, of shooting wild animals, the writer’s disclaimer is a surprise, says radio interview recordings and documentary championship ight with Gene Tunney in and of boxing, Ernest Hemingway Lydia Monin, author of From Poverty Bay to footage of the early 20th century local hero. 1928 in New York. Aonce wrote an angry letter of Broadway: he Story of Tom Heeney. hat Hemingway enclosed a copy of the letter Heeney and Hemingway became friends denial to the journalist who claimed the letter, tapped out on a typewriter, features in with a letter he wrote to his friend Tom after the Gisborne boxer retired from boxing famous author had knocked out Gisborne the exhibition Of the Canvas at Tairawhiti Heeney, which is also in the exhibition. -

Saturday, October 31, 2020 Tears at Turnaround for CCS Disability Action

TE NUPEPA O TE TAIRAWHITI SATURDAY-SUNDAY, OCTOBER 31-NOVEMBER 1, 2020 HOME-DELIVERED $1.90, RETAIL $2.70 PAGE 4 BITTERSWEET QUAKE JOLTS TURKEY ‘GREAT JOB’ VOTE FOR ON MAKARETU BEREAVED ROAD PAGE 6 PAGE 13 BREACH No. 2 This drone image was shot from within Matawai farmer John Bracken’s property as part of the Gisborne District Council’s investigation into a second recent breach by Bracken of the Resource Management Act. During a hearing earlier this year, council witnesses told Judge Brian Dwyer the breach, as pictured, involved an estimated 120 cubic metres of soil being side cast during the creation of a track and bulldozed over the edge of this hill-face, where it inevitably fell into a tributary of the Motu River. GDC picture Matawai farmer sentenced to 150 hours community work EMBATTLED Matawai farmer John Highway 2 by an off-duty Gisborne by police and the Inland Revenue Judge Brian Dwyer declined the Bracken has been ordered to complete District Council employee. The state Department into alleged tax evasion application saying Bracken had not 150 hours community work for a second highway borders the 1680ha property. totalling $17 million, for which he is identified any consequences of conviction breach of the Resource Management Act, The offence involved Bracken bulldozing expected to stand trial later this year. as necessary for the legal proportionality committed while he was being prosecuted an estimated 120 cubic metres of soil off Those allegations have seen an test and even if he had, they would be for an earlier one. -

Download the Gisborne Wine Map Here

Vineyard Map TAIRĀWHITI GISBORNE WINE REGION TO OPOTIKI HWY 2 WAIPAOA ORMOND 10 BOND RD 12 HEXTON PATUTAHI HILLS GISBORNE HWY HWY TAIRĀWHITI 35 2 BACK ORMOND RD REGION BUSHMERE RD CENTRAL HWY 1 MATAWHERO 35 VALLEY MANUTUKE MAIN RD 4 PAPATU RD 2 RIVERPOINT RD 3 6 RIVERPOINT GLADSTONE RD AWAPUNI LYTON RD ORMOND RD 5 WHARERATA RD 11 FARMERS SOLANDER ST 8 MARKET HWY GISBORNE 7 2 MIDWAY BEACH CITY 9 TO N A P I E R WAIPAOA RIVER WAIKANAE BEACH PA C I F I C C OA S T WAINUI RD H I G H WAY MURIWAI BEACH HWY 35 KAITI BEACH WAINUI OKITU VISIT THE CELLAR DOOR SPONGE BAY WAINUI BEACH PLEASE CHECK WEBSITE FOR OPENING HOURS MILLTON VINEYARD & WINERY BRIDGE ESTATE BUSHMERE WINES 119 PAPATU ROAD, MANUTUKE, SPADE OAK WRIGHTS VINEYARD 16 RIVERPOINT ROAD, 166 MAIN ROAD, MAKARAKA, MATAWHERO WINES GISBORNE 19 SOLANDER STREET, AND WINERY MATAWHERO, GISBORNE GISBORNE 189 RIVERPOINT ROAD, 06 862 8680 GISBORNE 1093 WHARERATA ROAD, 027 620 0127 06 868 9317 GISBORNE [email protected] 06 867 0198 GISBORNE WWW.BRIDGEESTATE.CO.NZ OR 021 946 301 06 867 6140 WWW.MILLTON.CO.NZ WWW.SPADEOAK.CO.NZ 06 862 8746 OR 027 656 8222 WWW.BUSHMERE.COM WWW.MATAWHERO.CO.NZ WWW.WRIGHTSWINES.CO.NZ 1 2 3 4 5 6 VISIT AT THE FARMER’S MARKET VISIT BY APPOINTMENT SAMPLE THESE WINES AT THE LOCAL FARMER’S MARKET EVERY SATURDAY BETWEEN 9.30AM - 12.30PM BOND BLOCK WINES LONGBUSH WINES HIHI WINES STONEBRIDGE WINES WRIGHTS VINEYARD 35 BOND ROAD, ORMOND, 19 SOLANDER STREET, TW WINES 021 720 738 WWW.STONEBRIDGE.CO.NZ AND WINERY GISBORNE GISBORNE BACK ORMOND ROAD, GISBORNE WWW.HIHI.CO.NZ WWW.WRIGHTSWINES.CO.NZ DENNY. -

Leaderbrand Produce Limited

www.jas-anz.org/register Z2090600NH(Product) This is to certify Leaderbrand Produce Limited 352 Lytton Road, Gisborne, New Zealand. Has been found to be compliant in accordance with the standard: As declared by the Certification Body (AsureQuality Limited) for the production of the products mentioned on this certificate. New Zealand GAP – Version 6.0_ June 2013 – Option 3 The Benchmarked Scheme New Zealand GAP normative documents have achieved equivalent status to the GLOBALG.A.P. General Regulations Version 4.0-1_February 2012 & GLOBALG.A.P. IFA Control Points & Compliance Criteria -Fruit & Vegetables Version 4.0-1_February 2012, in accordance to the GLOBALG.A.P. Benchmarking Procedure. At the following locations: See attached list. Product Sub-Scope GLOBALG.A.P. Certificate Number Produce Handling Country of Destination Broccoli Fruit & Vegetables 00050-CNHFL-0002 Yes Includes New Zealand Lettuce Fruit & Vegetables 00050-CNHKC-0002 Yes Includes New Zealand Cabbage Fruit & Vegetables 00050-CNHHC-0002 Yes Includes New Zealand Radicchio Fruit & Vegetables 00050-CNHHL-0002 Yes Includes New Zealand Baby leaf salad crops Fruit & Vegetables 00050-CNHHV-0002 Yes Includes New Zealand Squash Fruit & Vegetables 00050-CNHHP-0002 Yes Includes European Union Melons Fruit & Vegetables 00050-CNHFV-0002 Yes Includes New Zealand Sweetcorn Fruit & Vegetables 00050-CNHFP-0002 Yes Includes European Union Grapes Fruit & Vegetables 00050-CNHHH-0002 Yes Includes New Zealand and Produce Handling Facilities Product(s) GGN Facility name and address All above -

Geology of the Raukumara Area

GEOLOGY OF THE RAUKUMARA AREA C. MAZENGARB I. G. SPEDEN (COMPILERS) r::; ,- _z-.o _z....... """""..- l """"""'" , - 2" "'-- <;; M .- L~ ., c.-. w. - I';; YOm H 100 , .-- ............, vm I ~ ...- , •~ O'. l wm ! ~" - ~ T_ 200 -- w i -- 38 ~~ • x ......., wo 0 ........ w - '-' JOO • ......... YIV> 53 ••~ """"- n ~ I YAm '00 12 0. .......... • 13 ~ -- T...-- n ........., ~ T_ ~ iw -- pr.Telfon:lian Y. '" " ""'.., " 290 112 '" " '00 17 Waiauan S. j Serravalilan 18 ~ ~ U 0 - 800 1 Lale il' ~ 21 0 ~~ URbumian ~ N 900 O~ So 16.4 ~ 1000 "3 w, Zi:: """"'" """""'" e L1J~ ~ ~ F U ~! 0 ! -- Po ~ """" ~ - W........ l. () 238 Chomon ..", 2ll.5 i """"""'" '" lot. 337 U 310 ..... ~ ~. -- l __ ~~ J IV> 8. """"""" W Oh .., Om ! Y..... .... JU -.. ". ... ~. 3" I-- """'.... t0 $elandl,n Teurlan Jo 61 .0 p 0"" "iH Danlan '" 0 o.w U 65.0 ..0 Mautridlllan '" 0 - > oh 0 ~ """'"'" c.....,.., ""''''''''''' N '" i " ""- op 0 E"'" .... ~ ............ L1J "'- c...-., T~"" ...J "' T~ Rm « '"""""" ... • j ... ll. g ~ """"""'" en .... 0 - ~ """'" i """- em 0" ~ ~ () ..... 5 c.- Cu ~ -........ , E ". w..- "'i Uk w --- """"""'v w "'3 ........, ~ T_ _. Vbo v_- """"-...... EN"""'" VN --........., ~• Co<_ '" i Puaroan 0 U TIlhonlan <S. Gisbomian V. Ii .~~ Lland&llo - "" .> 0 ONuan Ko .g~ O.m.Mlllal'l Vdo ~ """"'" N 0 0 159 """"""" A".", (/) -e- "" ti~ L1J - ~I I ~ ::;; ~~ ..- T....... ~ " ....- • "'" 180 T""""'" -... V. - ." --T_ """"" ... .... , ..........., 505 ~ I Ia w Xho ""'''''"''' Ho X~ 0 -- 80 ~ -""'"'" .- ""-w__ '0 ~ o- F...., - E -... j •• ~ '" ~ ~ 8m () X. Templetoniafl Orelian Interim New Zealand ." Carnian Kaihlkuan Gk" 0",., X~ w• geological time scale from 227 ·•0 Crampton et al. (1995), "• ladinian E"'" Xl >-1 ~ E• .., "" with geochronology after Z -~ , Gradstein & Ogg (1996) and Imbrie et al.