Discourse Analysis As Potential for Re-Visioning Music Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Second Uncorrected Proof ~~~~ Copyright

Into the Groove ~~~~ SECOND UNCORRECTED PROOF ~~~~ COPYRIGHT-PROTECTED MATERIAL Do Not Duplicate, Distribute, or Post Online Hurley.indd i ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~11/17/2014 5:57:47 PM Studies in German Literature, Linguistics, and Culture ~~~~ SECOND UNCORRECTED PROOF ~~~~ COPYRIGHT-PROTECTED MATERIAL Do Not Duplicate, Distribute, or Post Online Hurley.indd ii ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~11/17/2014 5:58:39 PM Into the Groove Popular Music and Contemporary German Fiction Andrew Wright Hurley Rochester, New York ~~~~ SECOND UNCORRECTED PROOF ~~~~ COPYRIGHT-PROTECTED MATERIAL Do Not Duplicate, Distribute, or Post Online Hurley.indd iii ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~11/17/2014 5:58:39 PM This project has been assisted by the Australian Government through the Australian Research Council. The views expressed herein are those of the author and are not necessarily those of the Australian Research Council. Copyright © 2015 Andrew Wright Hurley All Rights Reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation, no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval system, published, performed in public, adapted, broadcast, transmitted, recorded, or reproduced in any form or by any means, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. First published 2015 by Camden House Camden House is an imprint of Boydell & Brewer Inc. 668 Mt. Hope Avenue, Rochester, NY 14620, USA www.camden-house.com and of Boydell & Brewer Limited PO Box 9, Woodbridge, Suffolk IP12 3DF, UK www.boydellandbrewer.com ISBN-13: 978-1-57113-918-4 ISBN-10: 1-57113-918-4 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data CIP data applied for. This publication is printed on acid-free paper. Printed in the United States of America. -

Song List 2012

SONG LIST 2012 www.ultimamusic.com.au [email protected] (03) 9942 8391 / 1800 985 892 Ultima Music SONG LIST Contents Genre | Page 2012…………3-7 2011…………8-15 2010…………16-25 2000’s…………26-94 1990’s…………95-114 1980’s…………115-132 1970’s…………133-149 1960’s…………150-160 1950’s…………161-163 House, Dance & Electro…………164-172 Background Music…………173 2 Ultima Music Song List – 2012 Artist Title 360 ft. Gossling Boys Like You □ Adele Rolling In The Deep (Avicii Remix) □ Adele Rolling In The Deep (Dan Clare Club Mix) □ Afrojack Lionheart (Delicious Layzas Moombahton) □ Akon Angel □ Alyssa Reid ft. Jump Smokers Alone Again □ Avicii Levels (Skrillex Remix) □ Azealia Banks 212 □ Bassnectar Timestretch □ Beatgrinder feat. Udachi & Short Stories Stumble □ Benny Benassi & Pitbull ft. Alex Saidac Put It On Me (Original mix) □ Big Chocolate American Head □ Big Chocolate B--ches On My Money □ Big Chocolate Eye This Way (Electro) □ Big Chocolate Next Level Sh-- □ Big Chocolate Praise 2011 □ Big Chocolate Stuck Up F--k Up □ Big Chocolate This Is Friday □ Big Sean ft. Nicki Minaj Dance Ass (Remix) □ Bob Sinclair ft. Pitbull, Dragonfly & Fatman Scoop Rock the Boat □ Bruno Mars Count On Me □ Bruno Mars Our First Time □ Bruno Mars ft. Cee Lo Green & B.O.B The Other Side □ Bruno Mars Turn Around □ Calvin Harris ft. Ne-Yo Let's Go □ Carly Rae Jepsen Call Me Maybe □ Chasing Shadows Ill □ Chris Brown Turn Up The Music □ Clinton Sparks Sucks To Be You (Disco Fries Remix Dirty) □ Cody Simpson ft. Flo Rida iYiYi □ Cover Drive Twilight □ Datsik & Kill The Noise Lightspeed □ Datsik Feat. -

Oaklandpostonline.Com February 14, 2018 // Volume 43

Oakland University’s THE Independent Student OAKLAND POST Newspaper Feb. 14, 2018 NO MERCY FOR DETROIT The Grizz Gang makes lots of noise as Men’s Basketball defeats Detroit Mercy in intense rivalry game PAGE 10 LETTER GRADES HIGH ROPES EXPANSION PROGRESS Grading system to change this fall Trustees introduce plan and funding Christopher Reed talks safety and to letter grade scale for recreation expansion schedule concerns of the OC PAGE 4 PAGE 5 PAGE 8 Photo by Elyse Gregory / The Oakland Post ontheweb Tune in online to listen to Samana Sheikh’s interview with Muslim fashion icon Ruma Begum about life and issues. thisweek www.oaklandpostonline.com February 14, 2018 // Volume 43. Issue 20 POLL OF THE WEEK What do you wish was a Winter Olympics award? A “Biggest snowboarding faceplant” B “Most vigorous curling sweeper” C “Best hockey boxing match” D “Most stylish team uniforms” Vote at www.oaklandpostonline.com LAST WEEK’S POLL What did you think of the Super Bowl? A) Fly Eagles, fly! 17 votes | 49% B) It’s impossible for me to care less PHOTO OF THE WEEK 7 votes | 20% C) The kid who took a selfie with JT tho PREGAME PARTY // Before the fan-favorite rivalry game against the University of Detroit 7 votes | 20% Mercy, alumni gathered in the Oakland Center to relive younger days and hang out with everyone’s favorite mascot: The Grizz. D) The Tom Brady era is over Photo // Brendan Triola 4 votes | 11% Submit a photo to [email protected] to be featured. View all submissions at oaklandpostonline.com THIS WEEK IN HISTORY February 16, 1962 Michigan State University - Oakland held its first dramatic play with “Alice in Wonderland.” February 14, 1963 MSU - Oakland officially became Oak- land University, totally independent of 9 15 19 Michgan State University. -

SMPC 2011 Attendees

Society for Music Perception and Cognition August 1114, 2011 Eastman School of Music of the University of Rochester Rochester, NY Welcome Dear SMPC 2011 attendees, It is my great pleasure to welcome you to the 2011 meeting of the Society for Music Perception and Cognition. It is a great honor for Eastman to host this important gathering of researchers and students, from all over North America and beyond. At Eastman, we take great pride in the importance that we accord to the research aspects of a musical education. We recognize that music perception/cognition is an increasingly important part of musical scholarship‐‐and it has become a priority for us, both at Eastman and at the University of Rochester as a whole. This is reflected, for example, in our stewardship of the ESM/UR/Cornell Music Cognition Symposium, in the development of several new courses devoted to aspects of music perception/cognition, in the allocation of space and resources for a music cognition lab, and in the research activities of numerous faculty and students. We are thrilled, also, that the new Eastman East Wing of the school was completed in time to serve as the SMPC 2011 conference site. We trust you will enjoy these exceptional facilities, and will take pleasure in the superb musical entertainment provided by Eastman students during your stay. Welcome to Rochester, welcome to Eastman, welcome to SMPC 2011‐‐we're delighted to have you here! Sincerely, Douglas Lowry Dean Eastman School of Music SMPC 2011 Program and abstracts, Page: 2 Acknowledgements Monetary -

Techno's Journey from Detroit to Berlin Advisor

The Day We Lost the Beat: Techno’s Journey From Detroit to Berlin Advisor: Professor Bryan McCann Honors Program Chair: Professor Amy Leonard James Constant Honors Thesis submitted to the Department of History Georgetown University 9 May 2016 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements 3 Introduction 5 Glossary of terms and individuals 6 The techno sound 8 Listening suggestions for each chapter 11 Chapter One: Proto-Techno in Detroit: They Heard Europe on the Radio 12 The Electrifying Mojo 13 Cultural and economic environment of middle-class young black Detroit 15 Influences on early techno and differences between house and techno 22 The Belleville Three and proto-techno 26 Kraftwerk’s influence 28 Chapter Two: Frankfurt, Berlin, and Rave in the late 1980s 35 Frankfurt 37 Acid House and Rave in Chicago and Europe 43 Berlin, Ufo and the Love Parade 47 Chapter Three: Tresor, Underground Resistance, and the Berlin sound 55 Techno’s departure from the UK 57 A trip to Chicago 58 Underground Resistance 62 The New Geography of Berlin 67 Tresor Club 70 Hard Wax and Basic Channel 73 Chapter Four: Conclusion and techno today 77 Hip-hop and techno 79 Techno today 82 Bibliography 84 3 Acknowledgements Thank you, Mom, Dad, and Mary, for putting up with my incessant music (and me ruining last Christmas with this thesis), and to Professors Leonard and McCann, along with all of those in my thesis cohort. I would have never started this thesis if not for the transformative experiences I had at clubs and afterhours in New York and Washington, so to those at Good Room, Flash, U Street Music Hall, and Midnight Project, keep doing what you’re doing. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P. -

Words With...Mugstar

CABLE #7 THIS ISSUE: CONTRIBUTE: Mugstar Apposing Send your news stories to: Pacificstream Elevator’s Christmas Party [email protected] The Wombats Smiling Wolf Follow us on: Bendal Interlude www.twitter.com/elevatorstudios Miles Kane or www.facebook.com/elevatorstudios WORDS WITH...MUGSTAR Mugstar’s stats are impressive. Achievements in Mogwai and Wooden Shjips, signing to Important work out. Working with Rob Whitely, in White- 2010 alone stand at 2 albums, 1 single, 3 UK tours, Records and we will have some very exciting news wood Studios, has had a massive impact on this ap- 1 European tour, and 1 film credit. They’re listed in shortly, which will be a massive highlight.” proach and he has actively encouraged this. 5 top 50 albums of the year lists and appear at num- ber 6 in the NME’s top 10 noise rock bands. To say Do Mugstar feel the John Peel connection played “The reception to ‘Lime’ has been unbelievable. It’s they’ve put in the hours is a horrendous disservice an important part in their success? “By having John been called the ‘best space rock album of 2010’. to the work load they’ve undertaken. All this and Peel play our music he opened a lot of doors for us. We recently had a great review in Mojo magazine producing the best material of their lives? Though But for ourselves he somewhat validated what we and in a number of magazines in the States. We’ve they’ve been together 8 years, it seems Mugstar were doing at the time, making you realise you must had more press than ever before, so it’s been a very are just getting positive release started.. -

Triple J Hottest 100 of the Decade Voting List: AZ Artists

triple j Hottest 100 of the Decade voting list: A-Z artists ARTIST SONG 360 Just Got Started {Ft. Pez} 360 Boys Like You {Ft. Gossling} 360 Killer 360 Throw It Away {Ft. Josh Pyke} 360 Child 360 Run Alone 360 Live It Up {Ft. Pez} 360 Price Of Fame {Ft. Gossling} #1 Dads So Soldier {Ft. Ainslie Wills} #1 Dads Two Weeks {triple j Like A Version 2015} 6LACK That Far A Day To Remember Right Back At It Again A Day To Remember Paranoia A Day To Remember Degenerates A$AP Ferg Shabba {Ft. A$AP Rocky} (2013) A$AP Rocky F**kin' Problems {Ft. Drake, 2 Chainz & Kendrick Lamar} A$AP Rocky L$D A$AP Rocky Everyday {Ft. Rod Stewart, Miguel & Mark Ronson} A$AP Rocky A$AP Forever {Ft. Moby/T.I./Kid Cudi} A$AP Rocky Babushka Boi A.B. Original January 26 {Ft. Dan Sultan} Dumb Things {Ft. Paul Kelly & Dan Sultan} {triple j Like A Version A.B. Original 2016} A.B. Original 2 Black 2 Strong Abbe May Karmageddon Abbe May Pony {triple j Like A Version 2013} Action Bronson Baby Blue {Ft. Chance The Rapper} Action Bronson, Mark Ronson & Dan Auerbach Standing In The Rain Active Child Hanging On Adele Rolling In The Deep (2010) Adrian Eagle A.O.K. Adrian Lux Teenage Crime Afrojack & Steve Aoki No Beef {Ft. Miss Palmer} Airling Wasted Pilots Alabama Shakes Hold On Alabama Shakes Hang Loose Alabama Shakes Don't Wanna Fight Alex Lahey You Don't Think You Like People Like Me Alex Lahey I Haven't Been Taking Care Of Myself Alex Lahey Every Day's The Weekend Alex Lahey Welcome To The Black Parade {triple j Like A Version 2019} Alex Lahey Don't Be So Hard On Yourself Alex The Astronaut Not Worth Hiding Alex The Astronaut Rockstar City triple j Hottest 100 of the Decade voting list: A-Z artists Alex the Astronaut Waste Of Time Alex the Astronaut Happy Song (Shed Mix) Alex Turner Feels Like We Only Go Backwards {triple j Like A Version 2014} Alexander Ebert Truth Ali Barter Girlie Bits Ali Barter Cigarette Alice Ivy Chasing Stars {Ft. -

10 Years After the Fall "/Noticed Immediately That East Berlin Just Wasn't Caught up to the Times." Kellie Hazell

------------ ------------------~ So long 311 The fall of the Wall 311 recently released a new album that has received Read viewpoint to find a number of different opin Tuesday mixed reviews. Read Scene's review of the alternative ions on thew-year anniversary of the destruction band's new album. of the Berlin Wall. NOVEMBER9, Scene+ page 14-15 Viewpoint+ page 12-13 1999 THE The Independent Newspaper Serving Notre Dame and Saint Mary's VOL XXXIII NO. 48 HTTP://OBSERVER.N D.EDU 10 years after the fall "/noticed immediately that East Berlin just wasn't caught up to the times." Kellie Hazell • Students tell of + The fall marked living in Germany the beginning of during the fall Germany's struggle for By NORREEN GILLESPIE reunification Saint Mary's Editor By ERIN LARUFFA l.ikn any othnr studnnt in his News Writer sixth gradn history class, Luis Matos sat. down with volumes of nrH:yclopndias and began to The Berlin Wall. along with its write a rPport about Germany barbed wire and checkpoint - spncilkally, tlw BPrlin Wall. towers, still remains a symbol of Tlwn lw found out lw was the Cold War and 20th enntury moving tlwrn. international polities. Today, in Tlw thought was tnrrifying to the place of one famous ehm~k LIH' middiP srhooler, who knnw point, stands Berlin Checkpoint Pnough about thP current Chari ie Plaza, an eight-story nvm1ts in Novemlwr of 1 t)81J to modern oflkn tower, according know that hn didn't want to livn to Business Week. in btst (;nrmany. Clearly, change in Germany "Whnn I !ward wn would bn and Europe in general has bflen moving to Gnrmany. -

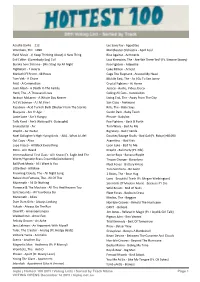

Triple J Hottest 100 2011 | Voting Lists | Sorted by Track Name Page 1 VOTING OPENS December 14 2011 | Triplej.Net.Au

Azealia Banks - 212 Les Savy Fav - Appetites Wombats, The - 1996 Manchester Orchestra - April Fool Field Music - (I Keep Thinking About) A New Thing Rise Against - Architects Evil Eddie - (Somebody Say) Evil Last Kinection, The - Are We There Yet? {Ft. Simone Stacey} Buraka Som Sistema - (We Stay) Up All Night Foo Fighters - Arlandria Digitalism - 2 Hearts Luke Million - Arnold Mariachi El Bronx - 48 Roses Cage The Elephant - Around My Head Tom Vek - A Chore Middle East, The - As I Go To See Janey Feist - A Commotion Crystal Fighters - At Home Juan Alban - A Death In The Family Justice - Audio, Video, Disco Herd, The - A Thousand Lives Calling All Cars - Autobiotics Jackson McLaren - A Whole Day Nearer Living End, The - Away From The City Art Vs Science - A.I.M. Fire! San Cisco - Awkward Kasabian - Acid Turkish Bath (Shelter From The Storm) Kills, The - Baby Says Bluejuice - Act Yr Age Caitlin Park - Baby Teeth Lanie Lane - Ain't Hungry Phrase - Babylon Talib Kweli - Ain't Waiting {Ft. Outasight} Foo Fighters - Back & Forth Snakadaktal - Air Tom Waits - Bad As Me Drapht - Air Guitar Big Scary - Bad Friends Noel Gallagher's High Flying Birds - AKA…What A Life! Douster/Savage Skulls - Bad Gal {Ft. Robyn}+B1090 Cut Copy - Alisa Argentina - Bad Kids Lupe Fiasco - All Black Everything Loon Lake - Bad To Me Mitzi - All I Heard Drapht - Bali Party {Ft. Nfa} Intermashional First Class - All I Know {Ft. Eagle And The Junior Boys - Banana Ripple Worm/Hypnotic Brass Ensemble/Juiceboxxx} Tinpan Orange - Barcelona Ball Park Music - All I Want Is You Fleet Foxes - Battery Kinzie Little Red - All Mine Tara Simmons - Be Gone Frowning Clouds, The - All Night Long 2 Bears, The - Bear Hug Naked And Famous, The - All Of This Lanu - Beautiful Trash {Ft. -

Gadir2014.Pdf (1.899Mb)

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Thesis Declaration I, Tami Gadir, certify that the thesis has been composed by me, that the work is my own, and that the work has not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification. Signed: Tami Gadir 1 Musical Meaning and Social Significance Techno Triggers for Dancing Tami Gadir Doctor of Philosophy University of Edinburgh 2014 2 Contents Abstract .................................................................................................................................... 4 Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................. 5 Guide to Reading Thesis with Audio and Video ...................................................................... -

Miles Kane Releases Debut Solo Single Claudia Pink's X

CABLE #6 THIS ISSUE: CONTRIBUTE: Miles Kane Milky Tea Send your news stories to: Claudia Pink Studio Liverpool [email protected] Wombats Owls* Follow us on: Bicycle Thieves In The Room Print Company www.twitter.com/elevatorstudios Mugstar Ditto Music or www.facebook.com/elevatorstudios MILES KANE RELEASES DEBUT SOLO SINGLE Last Shadow Puppet and former Rascals front- man Miles Kane has released his first solo single, ‘Inhaler’ after completing a short tour of the UK. With support from friends and fellow Elevator band, Bi- cycle Thieves, Miles took his highly anticipated material on the road. After performing a free gig at Liverpool Music Week, the tour culminated in Kane’s first lone London date at The Water Rats. ‘Inhaler’ was released on November 22nd on Columbia re- cords and is a tribute to Los Angeles’ psychedelic garage group Bonniwell Music Machine - ‘Inhaler’ is an adapta- tion of their 1969 track ‘Mother Nature Father Earth’. “I loved the guitar riff on ‘Mother Nature Father Earth’,” explains Miles. “It’s got a real groove to it and this riff inspired me to build a song around it which then became ‘Inhaler’.” The b-side features a cover version of another of Miles’ vin- tage influences, a dazzling take on Lee Hazlewood’s psych- pop classic, ‘Rainbow Woman’. The record is available as a limited edition 7” vinyl single and includes a special poster. The track will also be avail- able as a digital download. Miles has announced details of a full UK tour in January and March, and will be playing at the Sound City 2011 Launch Party Miles Kane on February 25th at the Kazimier.