Structure Preservation and the Syllable Coda in English*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Acoustic Analysis of English Codas by Mandarin Learners of English

SST 2012 Acoustic Analysis of English Codas by Mandarin Learners of English Nan Xu and Katherine Demuth Child Language Lab, Linguistics Department, ARC Centre of Excellence in Cognition and its Disorders, Macquarie University [email protected] this coda voicing contrast as Mandarin does not allow for stop Abstract codas, but with increased exposure to native English, their Mandarin has a much more limited segmental inventory than production should match more closely that of native English English, and permits only nasals in coda position, presenting a speakers [6]. Production studies of native English-speaking challenge for learners of English. However, previous studies adults show that there are many potential cues to stop coda have mainly explored this issue using perceptual transcription. voicing, including the duration of the preceding vowel, This study provides an acoustic analysis of coda consonant presence of a voice bar (i.e., low-frequency periodicity productions by Mandarin L2 learners of Australian English. indicating continued vocal fold vibration after oral closure), The results indicate that they produced voiceless stop and closure duration and the presence of aspiration noise produced fricative codas well, but exhibit considerable difficulty with after the oral release [5, 9, 11]. However, the results from [6] voicing contrasts and coda clusters. These findings and their showed that, regardless of length of exposure to English, theoretical implications for current models of L2 learning are Mandarin speakers had non-native acoustic measures for coda discussed. voicing contrasts (closure duration, vowel duration, and changes in F1) and used voice bar to indicate voicing on less Index Terms: Mandarin, English, second language learning, than 20% of the target /d/ codas. -

PREAMBLE Co-Dependents Anonymous Is a Fellowship of Men and Women Whose Common Purpose Is to Develop Healthy Relationships

PREAMBLE Co-Dependents Anonymous is a fellowship of men and women whose common purpose is to develop healthy relationships. The only requirement for membership is a desire for healthy and loving relationships. We gather together to support and share with each other in a journey of self-discovery- learning to love the self. Living the program allows each of us to become increasingly honest with ourselves about our personal histories and our own codependent behaviors. We rely upon the Twelve Steps and Twelve Traditions for knowledge and wisdom. These are the principles of our program and guides to developing honest and fulfilling relationships with ourselves and others. In CoDA we each learn to build a bridge to a Higher Power of our own understanding, and we allow others the same privilege. This renewal process is a gift of healing for us. By actively working the program of Co-Dependents Anonymous, we can each realize a new joy, acceptance, and serenity in our lives. WELCOME (Short Version) We welcome you to Co-Dependents Anonymous - a program of recovery from codependence, where each of us may share our experience, strength, and hope in our efforts to find freedom where there has been bondage, and peace where there has been turmoil in our relationships with others and ourselves. Codependence is a deeply-rooted, compulsive behaviour. It is born out of our sometimes moderately, sometimes extremely dysfunctional family systems. We attempted to use others as our sole source of identity, value, well-being, and as a way of trying to restore our emotional losses. -

"Courts Have Twisted Themselves Into Knots": US Copyright Protection for Applied Art

Columbia Law School Scholarship Archive Faculty Scholarship Faculty Publications 2016 "Courts Have Twisted Themselves into Knots": US Copyright Protection for Applied Art Jane C. Ginsburg Columbia Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, Intellectual Property Law Commons, and the Torts Commons Recommended Citation Jane C. Ginsburg, "Courts Have Twisted Themselves into Knots": US Copyright Protection for Applied Art, COLUMBIA JOURNAL OF LAW & THE ARTS, VOL. 40, P. 1, 2016; COLUMBIA PUBLIC LAW RESEARCH PAPER NO. 14-526 (2016). Available at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship/2000 This Working Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Scholarship Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarship Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. [For Columbia Journal of Law & the Arts, 100916; rev 200916; 051016] “Courts have twisted themselves into knots”: US Copyright Protection for Applied Art Jane C. Ginsburg, Columbia University School of Law* Abstract: In copyright law, the marriage of beauty and utility often proves fraught. Domestic and international law makers have struggled to determine whether, and to what extent, copyright should cover works that are both artistic and functional. The U.S. Copyright Act protects a work of applied art "only if, and only to the extent that, its design incorporates pictorial, graphic, or sculptural features that can be identified separately from, and are capable of existing independently of, the utilitarian aspects of the article." While the policy goal to separate the aesthetic from the functional is clear, courts' application of the statutory "separability" standard has become so complex and incoherent that the U.S. -

WHOM SAY YE THAT I AM? (An Easter Cantata) by LYLE HADLOCK

WHOM SAY YE THAT I AM? (An Easter Cantata) BY LYLE HADLOCK Flute ¡ 4 ú ú . j ú Ï ú Ï. Ï Ï . & 4 Î Ï Ï Ï bÏ Ï J bú ¢ (spoken narration) He lived here on earth 2000 years ago. He was the only person that was without sin and completely without blemish. 4 j & 4 w Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Ï Piano w mp ú. Ï Ï bú. Ï ú úÏ. bú. Ï w w ú ú ? 4 w w w ú ú w = 6 Fl. ¡ Ï Ï ú. ú Ï. Ï & Ï ú Ï Ï Ï ú Ï. J J w ¢ He is known by many names, but most commonly as Jesus Christ. Let's step back in time to clearly understand the role our Savior played, His love, and the sacrifice He made for us. & Ï ú ÏÏ Ï w w ú. Ï Ï Pno ú. Ï Ï ú Ï Ï w ú. Ï Ï w w w ? ú ú ú ú ú ú ú ú w w w 11 = U Ï Fl. ¡ j Ï. Ï & Ï Ï Ï. Ï ú. Î Î J w ¢ Countless Old Testament prophecies proclaimed His birth, His life, and His sacrifice. Matthew tells us "When Jesus (came unto His disciples and) asked, Whom do men say that I the Son of Man am? U Ï Ï ú ÏÏ ú Ï Ï Ï & Ï ú Ï ú Ï ú. Ï Pno ú Ï Ï ú. Ï mf . j Ï Ï ? ú ú ú. Ï ä ú Ï #w ú ú #ú. -

Dialect Use Within a Socially Fluid Group of Southern Resident Killer Whales, Orcinus Orca

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Master's Theses Fall 12-2014 Dialect Use Within a Socially Fluid Group of Southern Resident Killer Whales, Orcinus orca Courtney Elizabeth Smith University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses Part of the Animal Studies Commons, and the Zoology Commons Recommended Citation Smith, Courtney Elizabeth, "Dialect Use Within a Socially Fluid Group of Southern Resident Killer Whales, Orcinus orca" (2014). Master's Theses. 61. https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses/61 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi DIALECT USE WITHIN A SOCIALLY FLUID GROUP OF SOUTHERN RESIDENT KILLER WHALES, ORCINUS ORCA by Courtney Elizabeth Smith A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Approved: Dr. Stan Kuczaj_______________________ Committee Chair Dr. Alen Hajnal_______________________ Dr. Sheree Watson____________________ Dr. Karen Coats______________________ Dean of the Graduate School December 2014 ABSTRACT DIALECT USE WITHIN A SOCIALLY FLUID GROUP OF SOUTHERN RESIDENT KILLER WHALES, ORCINUS ORCA by Courtney Elizabeth Smith December 2014 Resident killer whales, Orcinus orca, of the Northeastern Pacific form stable kinship-based matrifocal associations and communicate with group-specific repertoires of discrete calls (dialects) that reflect these associations. The gradual fission of matrilines is usually consistent with dialect variations among groups that may manifest as differences in call usage at the repertoire level or subtle structural differences of the calls themselves. -

Notes on Daakie (Port Vato): Sounds and Modality

Proceedings of the Eighteenth Meeting of the Austronesian Formal Linguistics Association (AFLA) Lauren Eby Clemens Gregory Scontras Maria Polinsky (dir.) AFLA XVIII The Eighteenth Meeting of the Austronesian Formal Linguistics Association Harvard University March 4-6, 2011 NOTES ON DAAKIE (PORT VATO): SOUNDS AND MODALITY Manfred Krifka Zentrum für Allgemeine Sprachwissenschaft, Berlin & Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Table of Contents Preface i Byron Ahn Tongan Relative Clauses at the Syntax-Prosody 1-15 Interface Edith Aldridge Event Existentials in Tagalog 16-30 Laura Kalin and TP Serialization in Malagasy 31-45 Edward Keenan Manfred Krifka Notes on Daakie (Port Vato): Sounds and Modality 46-65 Eri Kurniawan Does Sundanese have Prolepsis and/or Raising to 66-79 Object Constructions? Bradley Larson A, B, C, or None of the Above: A C-Command 80-93 Puzzle in Tagalog Anja Latrouite Differential Object Marking in Tagalog 94-109 Dong-yi Lin Interrogative Verb Sequencing Constructions in 110-124 Amis Andreea Nicolae and How Does who Compose? 125-139 Gregory Scontras Eric Potsdam A Direct Analysis of Malagasy Phrasal 140-155 Comparatives Chaokai Shi and A Probe-based Account of Voice Agreement in 156-167 T.-H. Jonah Linl Formosan Languages Doris Ching-jung Yen and Sequences of Pronominal Clitics in Mantauran 168-182 Loren Billings Rukai: V-Deletion and Suppletion The Proceedings of AFLA 18 NOTES ON DAAKIE (PORT VATO): SOUNDS AND MODALITY* Manfred Krifka Zentrum für Allgemeine Sprachwissenschaft, Berlin & Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin [email protected] The paper reports from ongoing field work on Daakie (South Ambrym, Vanuatu), also known as Port Vato. -

Editors' Note of Squawking Seagulls and The

THE BIBLE & CRITICAL THEORY Editors’ Note With this issue, the review section of Bible & Critical Theory begins a new series of “Books and Culture” review essays. Alongside traditional scholarly book reviews of select new titles in biblical studies, these review essays will feature critical, scholarly engagements, written by established biblical scholars, of books and general culture which are not, per se, directly addressing “biblical scholarship.” At times, the intersection with biblical studies will arise because of an author’s use of Bible—implicit or explicit—in a creative or literary work. Others, however, will feature books that closely intersect with history, literature, economics and cultural studies, critical theory and philosophy, or other fields of scholarship of interest to readers of Bible & Critical Theory. Leading off the series is Peter J. Sabo’s fine engagement with Karl Knausgaard. We welcome your suggestions for books of interest and hope that you find these essays stimulating. Please address your comments and suggestions for future titles to review (or reviewers of interest) to the Book Review Editor, Robert Paul Seesengood, at the address provided by the journal. We hope you enjoy this series. * Of Squawking Seagulls and the Mutable Divine: Karl Ove Knausgaard’s A Time for Everything (With Reference to My Struggle) Books & Culture Review Essay P.J. Sabo An albino, reclusive Noah; a raving, delusional Abel; an asthmatic, kind-hearted, but misunderstood Cain; a solipsistic, hermitic Ezekiel—these versions of biblical characters (among others) can be found in Karl Ove Knausgaard’s A Time for Everything. This novel is idiosyncratic and defies rigid definitions. -

End-Of-Life Care Planning Guide

End-of-Life Care Planning Guide INSIDE This RESOURCE PG. 10 Starting EOL Conversations PG. 18 Essential Legal Documents PG. 51 Funerals & Burial A RESOURCE FOR PLANNING END-OF-LIFE CARE End-of-Life Care Planning is not an easy subject, but with the right support, you can make decisions that honor your EOL wishes. Everyone who believes in me This manual serves as a guide to help inform you and your families with will have eternal life. information, resources, and tools to make thoughtful end-of-life John 3:15 decisions. And in so doing can offer peace of mind to everyone! A resource of the Office of Aging Ministry, Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston © 2020 End-of -Life Care Planning Guide A Planning Guide For End-of-Life Care Office of Aging Ministry Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston 2020 Prayer Leader: St. Paul VI once reflected: In our youth, the days are short and the years are long. In old age the years are short and the day’s long. Somebody should tell us, right from the start of our lives that we are dying. Then we might live to the limit every minute of every day. Do it! I say, whatever you want to do, do it now! There are only so many tomorrows! All: Heavenly Father, thank you for the gift of life! Grant that we recognize the brevity of this earthly journey so that we might abide more fully in your loving Presence. Guide us in building your Kingdom of love and mercy until that day when we shall be united with you and the communion of saints and angels. -

Coda NEW MEETING MINI STARTER KIT

CoDA NEW MEETING MINI STARTER KIT This minikit is provided free of charge. If after reading this you decide you would like to start a new CoDA group in your area we suggest that you order the full starters kit from National Service Office using the enclosed literature order form – this comes in a folder and includes a selection of CoDA pamphlets. The cost is $10 - postage is free. Both this kit and the full kit are available for download from: www.codependentsanonymous.org.au The full kit is over 50 pages long. CONTENTS Welcome Letter Starting A New Meeting Preamble & Welcome – read at the start of every meeting. 12 Steps & 12 Traditions – read at every meeting. Basic Meeting format Crosstalk Paragraph – read at most meetings Guidelines for sharing – read at most meetings The 12 Promises Contents page of FULL STARTER KIT Group Registration Form Literature order form – order the Full Starter Kit using this. CoDA Pamphlets: “Am I Codepependent” “What Is CoDA?” “Attending Meetings” National Meeting List Literature Order Form CoDA National Service Office Phone: 0417 995 111 Email: [email protected] Meeting Updates: [email protected] Co-Dependents Anonymous - National Service Office CoDA 41/1 Regent St, Redfern NSW 2016 Australia Phone: 0417 995 111 Australia Email: [email protected] AustralianWebsite: www.codependentsanonymous.org.au Dear Friend, Welcome! We welcome you to the Fellowship of Co-Dependents Anonymous. New groups are essential to keep CoDA a healthy, growing and recovering community. We are glad to receive your enquiry about starting a CoDA group. This Meeting Starter Kit is intended to to support you to do this even if you have no experience of 12 Step groups. -

Spatial and Temporal Variation in Sperm Whale Coda Vocalizations: Stable Usage and Local Dialects

ANIMAL BEHAVIOUR, 2005, 70, 191–198 doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2005.03.001 Spatial and temporal variation in sperm whale coda vocalizations: stable usage and local dialects LUKE RENDELL* & HAL WHITEHEAD† *Sea Mammal Research Unit, School of Biology, University of St Andrews yDepartment of Biology, Dalhousie University (Received 26 February 2004; initial acceptance 16 April 2004; final acceptance 26 October 2004; published online 10 May 2005; MS. number: 8022R) Variation in vocal repertoires within species can result from various processes, from genetic drift to cultural evolution. Studying the detailed nature of such variation over time and space can provide insight into these underlying processes. The temporal stability or otherwise of vocal variants is important information in assessing the possibility of interaction between vocal variation and genetic evolution, while the geographical scale of variation can give useful clues in detailing population structure, thus providing management information. We studied variation in the vocal output of sperm whales, Physeter macrocephalus, which use short stereotyped click sequences called codas in social contexts, over timescales of up to 6 years and spatial scales of up to 10 000 nautical miles. We found no evidence from either correlation or regression analyses for change over time in the coda output of known social units. We did, however, find evidence for reduced similarity over distances of 200–1000 km. The apparent temporal stability of coda output suggests the possibility of evolutionary interactions. The scale of spatial variation is broadly similar to estimated home range sizes for this species, and the potential for interbreeding over such distances suggests differences between areas may represent local dialects rather than geographical variation through isolation. -

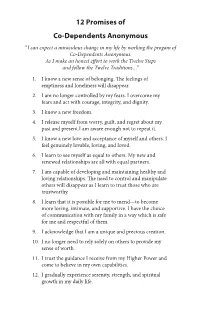

12 Promises of Co-Dependents Anonymous

12 Promises of Co-Dependents Anonymous “I can expect a miraculous change in my life by working the progam of Co-Dependents Anonymous. As I make an honest effort to work the Twelve Steps and follow the Twelve Traditions…” 1. I know a new sense of belonging. The feelings of emptiness and loneliness will disappear. 2. I am no longer controlled by my fears. I overcome my fears and act with courage, integrity, and dignity. 3. I know a new freedom. 4. I release myself from worry, guilt, and regret about my past and present.I am aware enough not to repeat it. 5. I know a new love and acceptance of myself and others. I feel genuinely lovable, loving, and loved. 6. I learn to see myself as equal to others. My new and renewed relationships are all with equal partners. 7. I am capable of developing and maintaining healthy and loving relationships. The need to control and manipulate others will disappear as I learn to trust those who are trustworthy. 8. I learn that it is possible for me to mend—to become more loving, intimate, and supportive. I have the choice of communication with my family in a way which is safe for me and respectful of them. 9. I acknowledge that I am a unique and precious creation. 10. I no longer need to rely solely on others to provide my sense of worth. 11. I trust the guidance I receive from my Higher Power and come to believe in my own capabilities. 12. I gradually experience serenity, strength, and spiritual growth in my daily life. -

The Usage and Symbolic Meaning of a Length of White Cotton Cloth Used in Shamanist Rituals for the Dead in Korea

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2008 The Usage and Symbolic Meaning of a Length of White Cotton Cloth Used in Shamanist Rituals for the Dead in Korea Jeeun Kim [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons Kim, Jeeun, "The Usage and Symbolic Meaning of a Length of White Cotton Cloth Used in Shamanist Rituals for the Dead in Korea" (2008). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 238. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/238 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The Usage and Symbolic Meaning of a Length of White Cotton Cloth Used in Shamanist Rituals for the Dead in Korea Jeeun Kim [email protected] Good afternoon. I am Jeeun Kim. I am a working artist and I teach fiber-art classes at universities in Seoul, Korea. My interest in this topic began with a textile history class I took at UH. The class was taught by Pat Hickman, my mentor, and covered the history of world textiles and the social roles and transformation of traditional textiles. This class stimulated my curiosity about the textiles of my own culture. The class taught me to look not only at the appearance of textiles and how they are made but also to look at the social roles of textiles in Korean culture.