Purjea. Bengal District Gazetteers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Progress Report of Monitoring the Ragging Prevention Program for 3

Progress Report of Monitoring the Ragging Prevention Program For 3 Months of January, February & March of 2019 By Raj Kachroo Founder Trustee – Aman Satya Kachroo Trust. Monitoring Agency for the Project. 2nd April, 2019. SUMMARY PROGRESS IN BRIEF 1. The total number of complaints received from the 15th June 2009 till 31st March, 2019 is 5998. Complaints received in this quarter are 228.During this quarter 113 cases were closed at the Monitoring Agency level to the satisfaction of the complainant. 10 cases were escalated to UGC. 5 cases were closed by UGC after following the due process. As of now 15 cases are pending with UGC. 2. Progress on development of data base of colleges is good. We have a data set of about 47982 colleges. Out of which we have E mail & phone numbers for roughly 38100 colleges. ___________________________________________________________________________ 1 Support Aman Movement For Eradication of Ragging. 1800 180 55 22 [email protected] 3. The campaign to register on line for affidavits is growing & going on strong. It will continue to grow in the future. As of now we have a data set of 5763768 students & E mail/Phone Contact data of 3565500 parents. 4. Progress on self declaration of “Compliance of Regulations” by Colleges/Universities is poor. So far – no work has been done in this regard. 5. Exceptionally high numbers of complaints continue to be received from Medical Colleges across the country. 28 complaints were received in this quarter alone. 6. On awareness the Trust has two dedicated internet lease lines that send 150000 e-mails per day to students & parents to create awareness against Ragging. -

DISTRICT : Katihar

District District District District District Sl. No. Name of Husband's/Father,s AddressDate of Catego Full Marks Percent Choice-1 Choice-2 Choice-3 Choice-4 Choice-5 Candidate Name Birth ry Marks Obtained age (With Rank) (With Rank) (With Rank) (With Rank) (With Rank) DISTRICT : Katihar 1 KUMARI PUNAM SRI BALESHWAR c/o- sri baleshwar 01-Jan-85 BC 700 631 90.14 Banka (2) Bhagalpur (2) Munger (2) Khagaria (1) Katihar (1) BHARTIA MANDAL mandal vill - babudih post -bhurna via- bausi, banka. bihar pin code - 813119 2SARITA KUMARISRI ARVIND RAM c/o- sri arvind ram das 05-Feb-86 BC 700 607 86.71 Banka (4) Bhagalpur (5) Munger (6) Khagaria (2) Katihar (2) DAS vill- babudih post- bhurna via- basi, banka, bihar- 813119 3 BINA KUMARISRI RANJAY vill- rahimpur chaudhary 05-Mar-75 GEN 900 730 81.11 Khagaria (5) Begusarai (2) Samastipur (3) Purnia (3) Katihar (3) CHAUDHARY tola post- rahimpur distt- khagaria 4 UPASNA KUMARISRI SURENDRA c/o- sri om prakash 01-Mar-77 BC 900 719 79.89 Khagaria (6) Begusarai (4) Saharsa (3) Madhepura (1) Katihar (4) KUMAR ranjan ( advocate ) police station road khagaria, post + p.s.- khagaria 5 RENU KUMARI RAJ KISHOR vill-kwai 05-Jan-70 BC 700 558 79.71 Nalanda (9) Gaya (7) Jahanabad (8) Patna (10) Katihar (5) PRASAD po-dhobdhia ps-khodaging dis-nalanda pin-801303 6 BANITA BHARTISRI PERYAG SINHA village- rasulpur, post- 05-Jul-88 BC 700 537 76.71 Lakhisarai (21) Munger (27) Banka (17) Gaya (13) Katihar (6) baha choki, p.s.- medni choki, district- lakhisarai 7 BIBHA BHARTISRI NIRAJ KUMAR w/o- sri niraj kumar 05-Jan-78 BC 900 690 76.67 Banka (18) Bhagalpur (27) Munger (29) Katihar (7) Katihar (7) vill- kamardih post- giridhara distt- banka pin code- 813211 8 BIBHA BHARTISRI NIRAJ KUMAR w/o- sri niraj kumar 05-Jan-78 BC 900 690 76.67 Banka (18) Bhagalpur (27) Munger (29) Katihar (7) Katihar (7) vill- kamardih post- giridhara distt- banka pin code- 813211 9 REMA KUMARIRAGHVENDAR vill+p.o- padva, p.s- 10-Jan-74 GEN 800 612 76.5 Madhepura (2) Saharsa (4) Supaul (1) Purnia (5) Katihar (9) SHARMA murligunj, dist- madhepura, pincode- 852122. -

District Health Society, Araria

DISTRICT HEALTH SOCIETY, ARARIA Provisional Merit List of STS (Senior Tuberculosis Supervisor)_Advertisement Number : PR No.11882(Ni.Ni.) 2018-19 Date of Birth/ Matric Intermediate Graduation Deploma in Sanitary Inspector's Name of Applicant Coresspondence Address Age Computer Total Sl. Gender/ (25 Marks) (25 Marks) (25 Marks) (25 Marks) Driving (With Mobile Number as on Certificate Merit Remarks No. Category Licence Father/Husband) e-mail ID 01/09/2018 (Y/N) Point Full Obtain % Merit Full Obtain % Merit Full Obtain % Merit Full Obtain % Merit Application No. Application Year-Month- Marks Marks Marks Point Marks Marks Marks Point Marks Marks Marks Point Marks Marks Marks Point Day Mohallah - Lal kothi road 04.03.1992 PO + Dist. -katihar Jamshed Alam Male 26 yrs. 5 1 1 PIN - 854105 500 309 61.80 15.45 500 315 63.00 15.75 2400 1810 75.42 18.85 800 469 58.63 25.00 No Yes 75.05 S/O - Md. Jalil UR months 28 Mob : 9934410022 days E-mail : [email protected] At+P.0 - Safapur P/S - Nayagown 11.10.1995 Pintu Kumar Dist. - Begusarai Male 22 Yrs. 10 2 2 S/0 - Pawan Kumar PIN - 851129 500 302 60.40 15.10 500 356 71.20 17.80 800 515 64.38 16.09 900 658 73.11 25.00 Yes Yes 73.99 UR Months, 21 Singh Mob : 8405810667 Days Email - [email protected] At - Majkuri, PO - Singhari PS - Kochadhaman Dist.- Kishanganj 05.10.1994 Need to check Amit Kumar PIN - 855115 Male 23 Yrs. 10 3 3 500 310 62.00 15.50 500 339 67.80 16.95 1500 951 63.40 15.85 400 307 76.75 25.00 Yes Yes 73.30 matric, DSI Marks S/O - Janardan Sah Mob : 9534326592 UR Months, 27 sheet 9570424152 Days E-mail : [email protected] At + PO - Sri Nagar PS - K. -

Mission Growth(In English)

RuRal Development DepaRtment GoveRnment of BihaR April-June 2013 Issue Mission GGrroowwtthh InclusIve Development achIeveD through collectIve efforts Contents EDITORIAL PANEL: EDITORIAL 3 Mithilesh Kumar, Sanjay Krishna and Kumar Sidharth REVIEW Social audit conducted Samriddhi is a newsletter of the in Bhelwa 4 Rural Development INITIATIVE Department, Government of Bihar, Main Secretariat, Patna, MGNREGA Social Park in Bihar, India, 800 015. Katihar 5 WORKSHOP http://rdd.bih.nic.in/ A call for transparency 6 We look forward to your MGNREGA workshop reviews valuable comments and Programme Officers 7 suggestions to make this A sharing of ideas 8 newsletter a truly interactive communication platform to BDO workshop discusses key issues 9 help take our development initiatives forward. We seek SPOTLIGHT your support through Smooth delivery of IAY fund contributions in the form of to beneficiaries 10 letters, case studies and stories Saran, a MGNREGA of success, problematic issues, success story 12 news items, experiences, past SPECIAL STORY and upcoming events, as well as announcements. An action plan for progress 14 HAPPENINGS Please send your feedback and contributions to Revolutionary initiatives for MGNREGS 16 [email protected] Munger gets a mobile Compilation, Editing and inspector 17 Design: Media Transasia India Instant transfer of funds 18 Ltd, Gurgaon More power to e-Shakti 19 Training across levels 02 to strengthen MGNREGA 19 Editorial fter the success of the first edition of Samriddhi , the Rural Development Department, Government of Bihar, is back with the Asecond edition of the newsletter. Keeping a finger on the pulse of rural development in the state, the publication aims to bring you the latest updates on the state’s flagship programmes, achievements, challenges and solutions, and steps taken towards the future. -

Date of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY) 13-SEP-2017

Note: This sheet is applicable for uploading the particulars related to the unclaimed and unpaid amount pending with company. Make sure that the details are in accordance with the information already provided in e-form IEPF-2 CIN/BCIN L92110MH1982PLC028180 Prefill Company/Bank Name MUKTA ARTS LIMITED Date Of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY) 13-SEP-2017 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 77878.00 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0.00 Sum of matured deposit 0.00 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0.00 Sum of matured debentures 0.00 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0.00 Sum of application money due for refund 0.00 Redemption amount of preference shares 0.00 Sales proceed for fractional shares 0.00 Validate Clear Proposed Date of Investor First Investor Middle Investor Last Father/Husband Father/Husband Father/Husband Last DP Id-Client Id- Amount Address Country State District Pin Code Folio Number Investment Type transfer to IEPF Name Name Name First Name Middle Name Name Account Number transferred (DD-MON-YYYY) 114 PALAVAN SATHU, EZHIT NGR MUKT120447000103 Amount for unclaimed and A KANNAN ANNAMALAI INDIA Tamil Nadu 632002 34.00 06-Oct-2018 VELLOR 7093 unpaid dividend ABDULMABINCHO VILL- HALDINAW PARA P.O- MUKTIN3002631018 Amount for unclaimed and ABDUL NAYEEM INDIA West Bengal 713513 15.00 06-Oct-2018 WDHURY HALDINAW PARA DIST- BURDWAN 2757 unpaid dividend 23 A SEWA NAGAR MARKET NEW MUKTIN3001181062 Amount for unclaimed and ADITYA BHARDWAJ RPSHARMA INDIA Delhi 110003 100.00 06-Oct-2018 DELHI 8002 unpaid dividend AT BANARAS CHOWK -

Break-Up of Contesting Candidates

1- Dhanaha 1. No. and Name of the Constituency : : 1 - Dhanaha 2. Form Unique Serial Number (FUSN) Prefix : : KMQ 3. Type of Constituency (Gen/SC/ST) : : GEN 4. Name and Designation of the Returning Officer : Sri M.Jaya Deputy Director, Consolidation, West Champaran 5. Date of Poll 13/11/05 6. Date of Repoll (if any) - 7. Date of Commencement of Counting 22-Nov-2005 8. Date of Declaration of Result 22-Nov-2005 9. Data About Polling Stations : Regular Polling Stations - 129 Average No. of Electors Per Polling Station - 876 Auxilliary Polling Stations 9 Average No. of Voters Per Polling Station - 429 Total Polling Stations 138 10. Data About Candidates : Men Women Total No. of Nomination Filed : 11 0 11 No. of Nomination Rejected : 0 0 0 No. of Nomination found correct after scrutiny : 11 0 11 No. of Withdrawals : 0 0 0 No. of Contesting Candidates : 11 0 11 No. of Candidates who forfeited their deposits : 8 0 8 Break-Up of Contesting Candidates National Parties : 1 0 1 State Parties : 4 0 4 Registered (Unrecognised) Parties : 2 0 2 Independents : 4 0 4 11. Details about Electors : General Service Total Male 68,015 5 68,020 Female 52,823 3 52,826 Total 120,838 8 120,846 12. Details about Voters : General Postal Total Male 33,424 0 33,424 Female 25,829 0 25,829 Total 59,253 0 59,253 Rejected Votes 0 Missing Votes 0 1- Dhanaha 13. Names of Contesting Candidates and their details : Sl. Candidate Name & Address SC/ Sex Party Symbol Final No. -

TRIANGL Priority Claimed from 27/06/2014; Application No

Trade Marks Journal No: 1957 , 20/07/2020 Class 35 TRIANGL Priority claimed from 27/06/2014; Application No. : 303048543 ;Hong Kong 2868851 23/12/2014 TRIANGL LIMITED 21/F., Edinburgh Tower, The Landmark, 15 Queen-s Road, Central, Hong Kong Manufacturers, merchants and service providers Address for service in India/Attorney address: LALL & SETHI D-17, N.D.S.E.-II NEW DELHI-49 Used Since :31/12/2012 DELHI Retail services, wholesale services, mail order services and online retailing in respect of clothing, footwear, headgear, brassieres, corsets (underclothing), singlets, body suits, body dresses, bodices (lingerie), petticoats, leotards, nightgowns, pyjamas, dressing gowns, nightcaps, pullovers, swimming trunks, beach clothes, underwear, bath robes, bikinis, bathing suits, bathing drawers, bathing caps, beach pareos, wristbands (clothing), headbands (clothing), slim pants, skirts, undershirts, T-shirts, sweatshirts, shawls, sandals, bath sandals, sneakers, flip-flops (footwear), sun visors (headwear), shower caps and swimming caps; advertising; business management. 7342 Trade Marks Journal No: 1957 , 20/07/2020 Class 35 LIVE WILD 2923883 16/03/2015 BLUE PLANET LIFESTYLE PRIVATE LIMITED trading as ;BLUE PLANET LIFESTYLE PRIVATE LIMITED H. No. 1622/13, Govindpuri, C.R. Park, New Delhi 110019 MANUFACTURER, MERCHANT AND SERVICE PROVIDER Address for service in India/Attorney address: AMIT KUMAR BHATNOTRA Flat No. 301, Plot No. A-74, Joshi Colony, Behind MCD Community Hall, I.P. Extension, Delhi 110092 Used Since :01/01/2015 DELHI ADVERTISING, BUSINESS MANAGEMENT AND ADMINISTRATION, ON-LINE ADVERTISING ON A COMPUTER NETWORK, OUTSOURCING SERVICES, PRESENTATION OF GOODS AND SERVICES ON COMMUNICATION MEDIA FOR RETAIL PURPOSES, PROCUREMENT SERVICES FOR OTHERS, ON-LINE TRADING SERVICES TO FACILITATE THE SALE OF GOODS THROUGH COMPUTER NETWORK AND MARKETING OF GOODS AND SERVICES 7343 Trade Marks Journal No: 1957 , 20/07/2020 Class 35 ANTRIKSH GRAND 3046330 02/09/2015 ANTRIKSH IT DEVELOPERS (P) LTD. -

PROVISIONAL MERIT LIST for ANM ® District District District District District Sl

PROVISIONAL MERIT LIST FOR ANM ® District District District District District Sl. No. Name of Husband's/Father,s AddressDate of Catego Full Marks Percent Choice-1 Choice-2 Choice-3 Choice-4 Choice-5 Candidate Name Birth ry Marks Obtained age (With Rank) (With Rank) (With Rank) (With Rank) (With Rank) DISTRICT : Araria 1VEENA RANJAN village- rahimpur 05-Mar-75 GEN 900 730 81.11 Saharsa (2) Bhagalpur (10) Purnia (2) Araria (1) Jamui (6) CHOUDHARY CHOUDHARY choudhary tola, p.o.rahimpur, district khagaria 2 MANORAMA MUNA PRASADE vill-kundbapar 25-Dec-75 MBC 900 668 74.22 Sitamarahi (4) Begusarai (13) Samastipur (15) Purnia (8) Araria (2) KUMARI po-akangardhi ps-akangarsari dis-nalanda 3 GITA KUMARISHRI- ARVIND vill- machariyawan, 01-Feb-68 BC 900 646 71.78 Patna (91) Nalanda (58) Araria (3) Nawada (52) Sheikhpura (37) KUMAR post- fatuha, dist- patna ( bihar ) 803201. 4 KUMARI MEERA JAGERNATH vill- nakhoo mistry, 10-Oct-67 BC 900 636 70.67 Araria (4) Purnia (21) Nawada (69) Jahanabad (54) Muzaffarpur (53) SINHA SHARMA vill- nagar nousha, post- nagar nousha dist- nalanda ( bihar ) 5 PUNAM PARBHAYUGESHWER vill+post- gangapur, 15-Mar-77 BC 900 634 70.44 Madhepura (8) Supaul (6) Saharsa (20) Purnia (25) Araria (5) PARSAD YADEV bhaya- murliganj, disst- madhepura, pincode- 852122. 6 RANJANA SINHABIDHURANJAN vill- mahisota, po.- 25-Jun-69 BC 900 632 70.22 Banka (69) Bhagalpur (106) Katihar (26) Purnia (26) Araria (6) UBHAR SINGH mahisota, p.s.- shambhuganj, dist- banka 7ALKA KUMARIBALI RAM KUMAR vill- mobarakpur, post- 02-Feb-86 BC 700 491 70.14 Araria (7) Purnia (27) Kishanganj (1) Katihar (27) Sitamarahi (16) NIRALA mainjar, dist- nalanda, pincode- 803117. -

Muradpur Teacher Merit List

iapk;r f'k{kd fu;kstu] 2019&20 dk vkSicaf/kd es/kk lwph fu;kstu bdkbZ dk uke %& xzke iapk;r jkt eqjkniqj iz[kaM dk uke %& lesyh ftyk dk uke %& dfVgkj lkekU; f'k{kd ¼oxZ 1 ls 5 rd½ Category :- UR(M) çkfIr ;ksX;rk dk çfr'kr vad BTET/ Ø0 dqy f'k{kd Øeka dqy es/kk CTET izf'k{k.k ;ksX;rk izf'k{k.k l0 vH;kFkhZ dk uke firk dk uke fyax tUe frfFk irk dksfV dk es/kk laLFkku dk uke ;ksX;rk ik=rk vH;qfDr d eSfVªd bUVj izf'kf{kr ;ksx vad osVst vad ijh{kk 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13vad 14 15 16 17 18 19 PRABHASH VILL+PO.- BASHA, PS.- PIPRA, 1 153 YOGANAND JHA M 01.10.1978 DIST.-SUPAUL UR 68.22 68.22 76.50 212.94 70.98 2 72.98 BSEB, PATNA Del.Ed BTET KUMAR JHA VILL- KATIHAR NEAR ENGLISH SANTOSH KUMAR GORECHANRA SCHOOL, LAL KOTHI ROAD, 2 246 M 25.02.1976 UR 72.22 69.77 69.28 211.27 70.42 2 72.42 NIOS Del.Ed BTET GHOSH GHOSH THANA+DIST.- KATIHAR- 854105 PRASHANT VILL SALAMPUR, P.O.- 3 33 PRABHAKAR JHA M 21.11.1982 KHAIRA,PS.- FALKA, DIST.- UR 56.71 66.33 73.96 197.00 65.67 2 67.67 BSEB, PATNA Del.Ed BTET KUMAR JHA KATIHAR ASHISH KUMAR VILL- SAKRAOULI, P.O.- 4 66 AJAY KUMAR JHA M 04.04.1994 SEMAPUR, PS.- BARARI, UR 71.80 60.00 61.24 193.04 64.35 2 66.35 CRSU JIND B.Ed. -

01- Ftyk Lrjh; Lhkh Egroiw.Kz Inkf/Kdkjh

01- ftyk Lrjh; lHkh egRoiw.kZ inkf/kdkjh Office Number Fax Sl. No Designation Name Office Address Mobile Number Email ID (with STD Code) Number 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 06452- 1 DEO Smt. PUNAM COLLOCTORIATE KATIHAR 06452-230581 9473191375 [email protected] 230880 SDO CAMPUS KATIHAR, 2 Deputy DEO RAMBABU DAS District Election Office, 06452-239911 8544429925 - [email protected] Katihar 063-KATIHAR, 3 NIRAJ KUMAR SDO OFFICE, KATIHAR - 9473191377 - [email protected], ERO 4 064-KADWA, ERO KHURSHID AKRAM DCLR OFFICE, BARSOI - 8544412336 - [email protected], 65-BALRAMPUR, 5 PAWAN KUMAR MANDAL SDO OFFICE, BARSOI - 9473191379 - [email protected], ERO 66-PRANPUR, VIKASH BHAWAN [email protected] 6 AMIT KUMAR PANDAY - 9431238345 - ERO KATIHAR [email protected] 67- SUB DIVISION OFFICE, 7 MANIHARI(ST), SANDEEP KUMAR - 9473191378 - [email protected], MANIHARI ERO 8 68-BARARI, ERO RAJEEV KUMAR DCLR OFFICE, KATIHAR - 8544412337 - [email protected] 9 69-KORHA, ERO KAMLESH KUMAR SINGH ADM OFFICE, KATIHAR - 9473191376 - [email protected] 10 ARO NIRAJ KUMAR SDO OFFICE, KATIHAR - 9473191377 - [email protected], 11 ARO KHURSHID AKRAM DCLR OFFICE, BARSOI - 8544412336 - [email protected], 12 ARO PAWAN KUMAR MANDAL SDO OFFICE, BARSOI - 9473191379 - [email protected], VIKASH BHAWAN [email protected], 13 ARO AMIT KUMAR PANDAY - 9431238345 - KATIHAR [email protected] SUB DIVISION OFFICE, 14 ARO SANDEEP KUMAR - 9473191378 - [email protected], MANIHARI 15 ARO RAJEEV KUMAR DCLR OFFICE, KATIHAR - 8544412337 - [email protected] NODAL OFFICER DISTRICT SUPLY OFFICER, 16 PRAMOD KUMAR - 9430925441 - [email protected] Training Cell KATIHAR NODAL OFFICER Complain 17 CHANDAN KUMAR MANDAL SPGRO KATIHAR - 9430252996 - [email protected] Monitoring Cell & SAMADHAN NODAL OFFICER 18 Communication MANI RANJAN SUB REGISTAR, KATIHAR - 9525054725 - [email protected] Cell Office Number Fax Sl. -

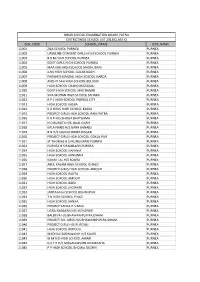

Sch Code School Name Dist Name 11001 Zila School

BIHAR SCHOOL EXAMINATION BOARD PATNA DISTRICTWISE SCHOOL LIST 2013(CLASS X) SCH_CODE SCHOOL_NAME DIST_NAME 11001 ZILA SCHOOL PURNEA PURNEA 11002 URSULINE CONVENT GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL PURNEA PURNEA 11003 B B M HIGH SCHOOL PURNEA PURNEA 11004 GOVT GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL PURNEA PURNEA 11005 MAA KALI HIGH SCHOOL MADHUBANI PURNEA 11006 JLNS HIGH SCHOOL GULAB BAGH PURNEA 11007 PARWATI MANDAL HIGH SCHOOL HARDA PURNEA 11008 ANCHIT SAH HIGH SCHOOL BELOURI PURNEA 11009 HIGH SCHOOL CHANDI RAZIGANJ PURNEA 11010 GOVT HIGH SCHOOL SHRI NAGAR PURNEA 11011 SIYA MOHAN HIGH SCHOOL SAHARA PURNEA 11012 R P C HIGH SCHOOL PURNEA CITY PURNEA 11013 HIGH SCHOOL KASBA PURNEA 11014 K D GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL KASBA PURNEA 11015 PROJECT GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL RANI PATRA PURNEA 11016 K G P H/S BHOGA BHATGAMA PURNEA 11017 N D RUNGTA H/S JALAL GARH PURNEA 11018 KALA NAND H/S GARH BANAILI PURNEA 11019 B N H/S JAGNICHAMPA NAGAR PURNEA 11020 PROJECT GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL GOKUL PUR PURNEA 11021 ST THOMAS H S MUNSHIBARI PURNEA PURNEA 11023 PURNEA H S RAMBAGH,PURNEA PURNEA 11024 HIGH SCHOOL HAFANIA PURNEA 11025 HIGH SCHOOL KANHARIA PURNEA 11026 KANAK LAL H/S SOURA PURNEA 11027 ABUL KALAM HIGH SCHOOL ICHALO PURNEA 11028 PROJECT GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL AMOUR PURNEA 11029 HIGH SCHOOL RAUTA PURNEA 11030 HIGH SCHOOL AMOUR PURNEA 11031 HIGH SCHOOL BAISI PURNEA 11032 HIGH SCHOOL JHOWARI PURNEA 11033 JANTA HIGH SCHOOL BISHNUPUR PURNEA 11034 T N HIGH SCHOOL PIYAZI PURNEA 11035 HIGH SCHOOL KANJIA PURNEA 11036 PROJECT KANYA H S BAISI PURNEA 11037 UGRA NARAYAN H/S VIDYAPURI PURNEA 11038 BALDEVA H/S BHAWANIPUR RAJDHAM -

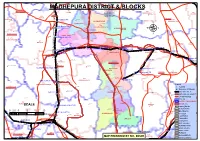

Madhepura District & Blocks

!. ÆR !. !. ÆR !. TRIVENIGANJ !. 045 CHHATAPUR Chakla Nirmali RS KOSI RIVER 044 KAMALPUR MSAUÆRPAUL DHEPURA DISTRICT & BLOCKS !. !. !. MADHUBA03N9I 042 TRIBENIGANJ (SC) 046 RANIGANJ PHULPARAS E PIPRA !. 049 N NARPATGANJ I KOSI RIVER !.BHARGAMA ARARIA SUPAL UL 043 Y KOSI RIVER A 081 SUPAUL BISHUNPUR SUNDAR !. W ARARIA GAMHARIA !. ALINAGAR L Bina Ekrna RS !. 047 GHANSHAMPUR I !. ÆR A SHANKERPUR RANIGANJ (SC) R SHANKARPUR GAMHARIA !. J N 072 Garh Baruari RS A ÆR SINGHESHWAR (SC) G KUMARKHAND !.KUMARKHAND P KIRATPUR JHAGRUA SINGHESHWAR !. NAUHATTA A !. T SINGHASWAR A !. DARBHANGA GHAILARH R !. µ P GHAILARH PATORI - ÆR !. SRINAGAR !. H PACHGACHHIA RS 079 !. !. GORA BAURAM R !.JAMALPUR 077 A G MAHISHI I 058 CHAMPANAGAR A !. !. KASBA R MADHEPURA A 073 ÆR BUDHMA RS S ÆR M!.URLIGANJ RS - BAIJNATHPUR RSMADHEPURA ÆR BANMAKHI DAURAM MADHEPURA RS ÆRMURLIGANJ RAMNAGAR PHARSAHÆR!.I A ÆR ÆRMurliganj RS !. ÆRBAIJNATHPATTI RS RAMNAGAR PHAÆRRSAHI S 059 Sarsi RS R MURLIGANJ BANMANKHI (SC) ÆR A SAHARSA RS !.SAHARSA H ÆR KAHARA NH !. -1 A 07 S MAHISHI !. Kirtiananagar RS SAUR BAZAR Aurahi RS ÆR!. 075 !. ÆR KRITYANAND NAGAR SAHARSA M MADHEPURA A KUSHESHWAR ASTHAN !. SN AHARSA PATARGHAT !. !. S 071 !. SONBARSA KACHARI RS I - BIHARIGANJ Barahara Kothi RS ÆR S ÆRBARHARA A GWALPARA !. 061 H Raghubanshnagar RS PURNIA DHAMDAHA A GOALPARA ÆR R !. DHAMDAHA S !. A !. - 074 BIHARIGÆRANJ B SIMRI BAKHTIPUR RS H SONBARSA (SC) BIHARIGANJ ÆR A !. 076 P SIMRI BAKHTIARPUR T Legend I A 140 SONBARSA KISHANGANJ !. SAMASTIPUR H !. !. TOWNS HASANPUR I !. ÆR R RAILWAY STATIONS A BANMA ITAHARI !. KOPARIA RS I BHAWANIPUR RAJDHAM RAILWAYLINES L KISHANGANJ !. !. SALKÆRHUA W FALKA NATIONAL HIGHWAYS A !.