The Power Within Us to Create the World Anew

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marge Piercy - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Marge Piercy - poems - Publication Date: 2004 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Marge Piercy(March 31, 1936) an American poet, novelist, and social activist. She is the author of the New York Times bestseller Gone to Soldiers, a sweeping historical novel set during World War II. Piercy was born in Detroit, Michigan, to a family deeply affected by the Great Depression. She was the first in her family to attend college, studying at the University of Michigan. Winning a Hopwood Award for Poetry and Fiction (1957) enabled her to finish college and spend some time in France, and her formal schooling ended with an M.A. from Northwestern University. Her first book of poems, Breaking Camp, was published in 1968. An indifferent student in her early years, Piercy developed a love of books when she came down with rheumatic fever in her mid-childhood and could do little but read. "It taught me that there's a different world there, that there were all these horizons that were quite different from what I could see," she said in a 1984 Wired interview. As of 2004 she is author of seventeen volumes of poems, among them The Moon is Always Female (1980, considered a feminist classic) and The Art of Blessing the Day (1999), as well as fifteen novels, one play (The Last White Class, co- authored with her third and current husband Ira Wood), one collection of essays (Parti-colored Blocks for a Quilt), one nonfiction book, and one memoir. Her novels and poetry often focus on feminist or social concerns, although her settings vary. -

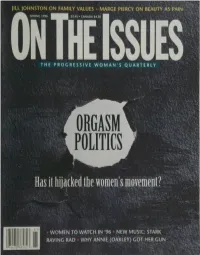

View Entire Issue in Pdf Format

JILL JOHNSTON ON FAMILY VALUES MARGE PIERCY ON BEAUTY AS PAIN SPRING 1996 $3,95 • CANADA $4.50 THE PROGRESSIVE WOMAN'S QUARTERLY POLITICS Has it hijackedthe women's movement? WOMEN TO WATCH IN '96 NEW MUSIC: STARK RAVING RAD WHY ANNIE (OAKLEY) GOT HER GUN 7UU70 78532 The Word 9s Spreading... Qcaj filewsfrom a Women's Perspective Women's Jrom a Perspective Or Call /ibout getting yours At Home (516) 696-99O9 SPRING 1996 VOLUME V • NUMBER TWO ON IKE ISSUES THE PROGRESSIVE WOMAN'S QUARTERLY features 18 COVER STORY How Orgasm Politics Has Hi j acked the Women's Movement SHEILAJEFFREYS Why has the Big O seduced so many feminists—even Ms.—into a counterrevolution from within? 22 ELECTION'96 Running Scared KAY MILLS PAGE 26 In these anxious times, will women make a difference? Only if they're on the ballot. "Let the girls up front!" 26 POP CULTURE Where Feminism Rocks MARGARET R. SARACO From riot grrrls to Rasta reggae, political music in the '90s is raw and real. 30 SELF-DEFENSE Why Annie Got Her Gun CAROLYN GAGE Annie Oakley trusted bullets more than ballots. She knew what would stop another "he-wolf." 32 PROFILE The Hot Politics of Italy's Ice Maiden PEGGY SIMPSON At 32, Irene Pivetti is the youngest speaker of the Italian Parliament hi history. PAGE 32 36 ACTIVISM Diary of a Rape-Crisis Counselor KATHERINE EBAN FINKELSTEIN Italy's "femi Newtie" Volunteer work challenged her boundaries...and her love life. 40 PORTFOLIO Not Just Another Man on a Horse ARLENE RAVEN Personal twists on public art. -

Famous People from Michigan

APPENDIX E Famo[ People fom Michigan any nationally or internationally known people were born or have made Mtheir home in Michigan. BUSINESS AND PHILANTHROPY William Agee John F. Dodge Henry Joy John Jacob Astor Herbert H. Dow John Harvey Kellogg Anna Sutherland Bissell Max DuPre Will K. Kellogg Michael Blumenthal William C. Durant Charles Kettering William E. Boeing Georgia Emery Sebastian S. Kresge Walter Briggs John Fetzer Madeline LaFramboise David Dunbar Buick Frederic Fisher Henry M. Leland William Austin Burt Max Fisher Elijah McCoy Roy Chapin David Gerber Charles S. Mott Louis Chevrolet Edsel Ford Charles Nash Walter P. Chrysler Henry Ford Ransom E. Olds James Couzens Henry Ford II Charles W. Post Keith Crain Barry Gordy Alfred P. Sloan Henry Crapo Charles H. Hackley Peter Stroh William Crapo Joseph L. Hudson Alfred Taubman Mary Cunningham George M. Humphrey William E. Upjohn Harlow H. Curtice Lee Iacocca Jay Van Andel John DeLorean Mike Illitch Charles E. Wilson Richard DeVos Rick Inatome John Ziegler Horace E. Dodge Robert Ingersol ARTS AND LETTERS Mitch Albom Milton Brooks Marguerite Lofft DeAngeli Harriette Simpson Arnow Ken Burns Meindert DeJong W. H. Auden Semyon Bychkov John Dewey Liberty Hyde Bailey Alexander Calder Antal Dorati Ray Stannard Baker Will Carleton Alden Dow (pen: David Grayson) Jim Cash Sexton Ehrling L. Frank Baum (Charles) Bruce Catton Richard Ellmann Harry Bertoia Elizabeth Margaret Jack Epps, Jr. William Bolcom Chandler Edna Ferber Carrie Jacobs Bond Manny Crisostomo Phillip Fike Lilian Jackson Braun James Oliver Curwood 398 MICHIGAN IN BRIEF APPENDIX E: FAMOUS PEOPLE FROM MICHIGAN Marshall Fredericks Hugie Lee-Smith Carl M. -

Kirsch, Gesa E., Ed. Ethics and Representation In

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 400 543 CS 215 516 AUTHOR Mortensen, Peter, Ed.; Kirsch, Gesa E., Ed. TITLE Ethics and Representation in Qualitative Studies of Literacy. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-1596-9 PUB DATE 96 NOTE 347p.; With a collaborative foreword led by Andrea A. Lunsford and an afterword by Ruth E. Ray. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 15969: $21.95 members, $28.95 nonmembers). PUB TYPE Collected Works General (020) Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC14 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Case Studies; Elementary Secondary Education; *Ethics; *Ethnography; Higher Education; Participant Observation; *Qualitative Research; *Research Methodology; Research Problems; Social Influences; *Writing Research IDENTIFIERS Researcher Role ABSTRACT Reflecting on the practice of qualitative literacy research, this book presents 14 essays that address the most pressing questions faced by qualitative researchers today: how to represent others and themselves in research narratives; how to address ethical dilemmas in research-participant relationi; and how to deal with various rhetorical, institutional, and historical constraints on research. After a foreword ("Considering Research Methods in Composition and Rhetoric" by Andrea A. Lunsford and others) and an introduction ("Reflections on Methodology in Literacy Studies" by the editors), essays in the book are (1) "Seduction and Betrayal in Qualitative Research" (Thomas Newkirk); (2) "Still-Life: Representations and Silences in the. Participant-Observer Role" (Brenda Jo Brueggemann);(3) "Dealing with the Data: Ethical Issues in Case Study Research" (Cheri L. Williams);(4) "'Everything's Negotiable': Collaboration and Conflict in Composition Research" (Russel K. -

Inter/View: Talks with America's Writing Women

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Literature in English, North America English Language and Literature 1990 Inter/View: Talks with America's Writing Women Mickey Pearlman Katherine Usher Henderson Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Pearlman, Mickey and Henderson, Katherine Usher, "Inter/View: Talks with America's Writing Women" (1990). Literature in English, North America. 56. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_english_language_and_literature_north_america/56 Inter/View Inter/View Talks with America's Writing Women Mickey Pearlman and Katherine Usher Henderson THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY PHOTO CREDITS: M.A. Armstrong (Alice McDermott), Jerry Bauer (Kate Braverman, Louise Erdrich, Gail Godwin, Josephine Humphreys), Brian Berman (Joyce Carol Oates), Nancy Cramp- ton (Laurie Colwin), Donna DeCesare (Gloria Naylor), Robert Foothorap (Amy Tan), Paul Fraughton (Francine Prose), Alvah Henderson (Janet Lewis), Marv Hoffman (Rosellen Brown), Doug Kirkland (Carolyn See), Carol Lazar (Shirley Ann Grau), Eric Lindbloom (Nancy Willard), Neil Schaeffer (Susan Fromberg Schaeffer), Gayle Shomer (Alison Lurie), Thomas Victor (Harriet Doerr, Diane Johnson, Anne Lamott, Carole -

Marge Piercy: Writer, Feminist, Activist: an Exhibit

Deep Blue Deep Blue https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/documents Research Collections Library (University of Michigan Library) 2004 Marge Piercy: Writer, Feminist, Activist: An Exhibit Beam, Kathryn http://hdl.handle.net/2027.42/120262 Downloaded from Deep Blue, University of Michigan's institutional repository marge pIercy• writer, feminist, activist Sponsored by: Arts at Michigan Arts of Citizenship Program Center for the Education of Women College of Literature, Science & the Arts Department of English Language and Literature Frankel Center for Judaic Studies Friends of the University Library Hopwood Program Horace H. Rackham School of Graduate Studies Institute for Research on Women and Gender Institute for the Humanities MFA Program in Creative Writing • Office of the President lllarge piercy Office of the Provost Office of the Vice President for Research writer, feminist, activist School of Information Special Collections Library University Library an exhibit Women's Studies Program September 1 to November 27, 2004 Curated by Kathryn Beam Credits: Jean Buescher Bartlett, brochure design Franki Hand, text and layout design Cover photo credit: Ira Wood Special Collections Library Copyright 2004 by the University of Michigan Library 711 Hatcher Graduate Library University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. University of Michigan University of Michigan Board of Regents: Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1205 David A. Brandon Andrea Fischer Newman Laurence B. Deitch (734) 764-9377 Andrew C. Richner Olivia P. Maynard S. Martin Taylor http://www.lib.um.ich.edu/ spec-colI Rebecca McGowan Katherine E. White Mary Sue Coleman (ex officio) [email protected] INTRODUCTION EARLY YEARS Cases 1 and 2 arge Piercy, who graduated from the University of Michigan with a Bachelor of Arts degree in arge Piercy attended the University of Michigan M 1957, is a world-renowned poet, novelist, and from 1953 to 1957. -

Phd Thesis Jayne Glover FINAL SUBMISSION

“A COMPLEX AND DELICATE WEB”: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF SELECTED SPECULATIVE NOVELS BY MARGARET ATWOOD, URSULA K. LE GUIN, DORIS LESSING AND MARGE PIERCY Thesis Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Rhodes University By Jayne Ashleigh Glover December 2007 Abstract This thesis examines selected speculative novels by Margaret Atwood, Ursula K. Le Guin, Doris Lessing and Marge Piercy. It argues that a specifiable ecological ethic can be traced in their work – an ethic which is explored by them through the tensions between utopian and dystopian discourses. The first part of the thesis begins by theorising the concept of an ecological ethic of respect for the Other through current ecological philosophies, such as those developed by Val Plumwood. Thereafter, it contextualises the novels within the broader field of science fiction, and speculative fiction in particular, arguing that the shift from a critical utopian to a critical dystopian style evinces their changing treatment of this ecological ethic within their work. The remainder of the thesis is divided into two parts, each providing close readings of chosen novels in the light of this argument. Part Two provides a reading of Le Guin’s early Hainish novels, The Left Hand of Darkness , The Word for World is Forest and The Dispossessed , followed by an examination of Piercy’s Woman on the Edge of Time , Lessing’s The Marriages Between Zones Three, Four and Five , and Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale . The third, and final, part of the thesis consists of individual chapters analysing the later speculative novels of each author. -

Queer Methods and Methodologies Queer Theories Intersecting and Social Science Research

Queer Methods and Queer Methods and Methodologies Methodologies provides the first systematic consideration of the implications of a queer perspective in the pursuit of social scientific research. This volume grapples with key contemporary questions regarding the methodological implications for social science research undertaken from diverse queer perspectives, and explores the limitations and potentials of queer engagements with social science research techniques and methodologies. With contributors based in the UK, USA, Canada, Sweden, New Zealand and Australia, this truly Queer Methods international volume will appeal to anyone pursuing research at the and Methodologies intersections between social scientific research and queer perspectives, as well as those engaging with methodological Intersecting considerations in social science research more broadly. Queer Theories This superb collection shows the value of thinking concretely about and Social Science queer methods. It demonstrates how queer studies can contribute to Research debates about research conventions as well as offer unconventional research. The book is characterised by a real commitment to queer as Edited by an intersectional study, showing how sex, gender and sexuality Kath Browne, intersect with class, race, ethnicity, national identity and age. Readers will get a real sense of what you can write in by not writing University of Brighton, UK out the messiness, difficulty and even strangeness of doing research. Catherine J. Nash, Sara Ahmed, Goldsmiths, University of London, UK Brock University, Canada Very little systematic thought has been devoted to exploring how queer ontologies and epistemologies translate into queer methods and methodologies that can be used to produce queer empirical research. This important volume fills that lacuna by providing a wide-ranging, comprehensive overview of contemporary debates and applications of queer methods and methodologies and will be essential reading for J. -

Diversity, Equity & Inclusion

MERCY HIGH SCHOOL MAGAZINE PUBLISHED TWICE YEARLY FOR ALUMNAE, PARENTS & FRIENDS FALL / WINTER 2020 Mya Williams '21 Susan Smith '84 Mary Harkness '70 Diversity, Equity & Inclusion Principal Patricia Sattler Julia Bishop '21 DEI Angela Rea '20 INSIDE THIS 2019-20 Honor Roll of Donors • Mercy Moments & Awards mhsmi.org I SSUE Staff Salute • Alumnae Class Notes CREATED BY MERCY’S FOUNDING MOTHER OF ART MARY IGNATIUS DENAY, RSM A MOSAIC IS AN ARRAY OF DIVERSE ELEMENTS JOINED TOGETHER TO CREATE A GREATER WHOLE. Mercy High School Board of Trustees Jared P. Buckley - Chair MHSMI.ORG Cheryl Delaney Kreger, Ed.D. ’66 - President Visit Diana Mercer-Pryor - Treasurer Stay connected with what's happening at Dave Hall - Secretary Mercy. Read and sign up to receive alumnae Nancy Auffenberg and parent e-newsletters, browse Anne Blake, Ph.D. Mercy High School the school year calendar, and check out Robert Casalou 29300 W. 11 Mile Road Mercy activities and news. Margaret Dimond, Ph.D. ’76 Susan Hartmus Hiser Farmington Hills, MI 48336-1409 Brigid Johnson, RSM Email: [email protected] Karla Rose Middlebrooks ’76 Tel: (248) 476-8020 Carla LaFave O’Malley ’70 Fax: (248) 476-3691 Marisa C. Petrella ’77 Mercy Sharon Sanderson Anita Sevier Paul E. Swanson MOSAIC Rita Marie Valade, RSM ’72 ERCY IGH CHOOL High School M H S Board Support Staff MAGAZINE Patricia Sattler - Principal MISSION STATEMENT Colleen McMaster ’81 Editors - Associate Principal Academic Affairs Julie Earle, Maria Siciliano Mueller - Director of Finance Mercy High School, Director of Communications -

A Network Analysis of Postwar American Poetry in the Age of Digital Audio Archives Ankit Basnet and James Jaehoon Lee

Journal of April 20, 2021 Cultural Analytics A Network Analysis of Postwar American Poetry in the Age of Digital Audio Archives Ankit Basnet and James Jaehoon Lee Ankit Basnet, University of Cincinnati James Lee, University of Cincinnati Peer-Reviewer: Stephen Voyce Data Repository: 10.7910/DVN/NK7Z2H A B S T R A C T From the New American Poetry to New Formalism, publishing networks such as literary magazines and social scenes such as poetry reading series have served as a capacious model for understanding the varied poetic formations in the postwar period. As audio archives of poetry readings have been digitized in large volumes, Charles Bernstein has suggested that open access to digital archives allows readers of American poetry to create mixtapes in different configurations. Digital archives of poetry readings “offer an intriguing and powerful alternative” to organizing practices such as networks and scenes. Placing Bernstein’s definition of the digital audio archive into contact with more conventional understandings of poetic community gives us a composite vision of organizing principles in postwar American poetry. To accomplish this, we compared poetry reading venues as well as audio archives — alongside more familiar print networks constituted by poetry anthologies and magazines — as important and distinct sites of reception for American poetry. We used network analysis to visualize the relationships of individual poets to venues where they have read, archives where their readings are stored, and text anthologies where their poetry has been printed. Examining several types of poetic archives offers us a new perspective in how we perceive the relationships between poets and their “networks and scenes,” understood both in terms of print and audio culture, as well as trends and changes in the formation of these poetic communities and affiliations. -

FP 12.3 Fall1992.Pdf (4.054Mb)

WOMEN'S STUDIES LIBRARIAN The University of Wisconsin System EMINIST ERIODICALS A CURRENT LISTING OF CONTENTS VOLUME 12, NUMBER 3 FALL 1992 Published by Phyllis Holman Weisbard Women's Studies Librarian University of Wisconsin System 430 Memorial Library / 728 State Street Madison, Wisconsin 53706 (608) 263-5754 EMINIST ERIODICALS A CURRENT LISTING OF CONTENTS Volume 12, Number 3 Fall 1992 Periodical literature isthe cutting edge of women's scholarship, feminist theory, and much of women's culture. Feminist Periodicals: A Current Listing ofContents is published by the OHice of the University of Wisconsin System Women's Studies Librarian on a quarterly basis with the intent of increasing public awareness of feminist periodicals. It is our hope that Feminist Periodicals will serve several purposes: to keep the reader abreast of current topics in feminist literature; to increase readers' familiarity with awide spectrum of feminist periodicals; and to provide the requisite bibliographic information should areader wish to subscribe to ajournal or to obtain a particular article at her library or through interlibrary loan. (Users will need to be aware of the limitations of the new copyright law with regard to photocopying of copyrighted materials.) Table of contents pages from current issues of major feminist journals are reproduced in each issue of Feminist Periodicals, preceded by a comprehensive annotated listing of all journals we have selected. As publication schedules vary enormously, not every periodical will have table of contents pages reproduced in each issue of FP. The annotated listing provides the following information on each journal: 1. Year of first publication. 2. Frequency of publication. -

Audre Lorde's Zami and the Death of Emmett Till

humanities Article The Averted Gaze: Audre Lorde’s Zami and the Death of Emmett Till Rachel Watson Department of English, Howard University, Washington, DC 20059, USA; [email protected] Received: 29 June 2019; Accepted: 2 August 2019; Published: 9 August 2019 Abstract: This essay considers Audre Lorde’s Zami: A New Spelling of My Name (1982) as an example of the neoliberal turn to memoir that both complicates and exemplifies important aspects of the relationship between literary form and ideological expressions of racial and sexual identity. By examining a hitherto un-noted omission from Lorde’s memoir, the death of Emmett Till, this essay illuminates the political significance behind Lorde’s choice to narrate Till’s death in the form of a poem while conspicuously omitting it from her prose memoir. Incorporating a broader selection of Lorde’s work, and comparative analysis with other poetic responses to Till’s death, this essay shows through this example how the intense personalization of an historical event can formalize the embodiment of an essentialized, and thus timeless, racial identity. As such, Lorde’s work demonstrates how literary form can both communicate and obscure paradoxical aspects of contemporary racial ideology by rationalizing the embodiment of racial difference in the post-Civil Rights world. Keywords: Audre Lorde; Emmett Till; African American literature; African American poetry; memoir; autobiography; feminism; sexuality; race; identity In becoming forcibly and essentially aware of my mortality, and of what I wished and wanted for my life, however short it might be, priorities and omissions became strongly etched in a merciless light, and what I most regretted were my silences.