Anglo-American Marital Relations 1870 - 1945 Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’S Daughters – Part 2

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations School of Arts and Sciences October 2012 Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 2 Cecilia S. Seigle Ph.D. University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Seigle, Cecilia S. Ph.D., "Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 2" (2012). Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations. 8. https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc/8 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc/8 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 2 Abstract This section discusses the complex psychological and philosophical reason for Shogun Yoshimune’s contrasting handlings of his two adopted daughters’ and his favorite son’s weddings. In my thinking, Yoshimune lived up to his philosophical principles by the illogical, puzzling treatment of the three weddings. We can witness the manifestation of his modest and frugal personality inherited from his ancestor Ieyasu, cohabiting with his strong but unconventional sense of obligation and respect for his benefactor Tsunayoshi. Disciplines Family, Life Course, and Society | Inequality and Stratification | Social and Cultural Anthropology This is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc/8 Weddings of Shogun’s Daughters #2- Seigle 1 11Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 2 e. -

The Rees and Carrington Extracts

THE REES AND CARRINGTON EXTRACTS CUMULATIVE INDEX – PEOPLE, PLACES AND THINGS – TO 1936 (INCLUSIVE) This index has been compiled straight from the text of the ‘Extracts’ (from January 1914 onwards, these include the ‘Rees Extracts’. – in the Index we have differentiated between them by using the same date conventions as in the text – black date for Carrington, Red date for Rees). In listing the movements, particularly of Kipling and his family, it is not always clear when who went where and when. Thus, “R. to Academy dinner” clearly refers to Kipling himself going alone to the dinner (as, indeed would have been the case – it was, in the 1890s, a men-only affair). But “Amusing dinner, Mr. Rhodes’s” probably refers to both of them going, and has been included as an entry under both Kipling, Caroline, and Kipling, Rudyard. There are many other similar events. And there are entries recording that, e.g., “Mrs. Kipling leaves”, without any indication of when she had come – but if it’s not in the ‘Extracts’ (though it may well have been in the original diaries) then, of course, it has not been possible to index it. The date given is the date of the diary entry which is not always the date of the event. We would also emphasise that the index does not necessarily give a complete record of who the Kiplings met, where they met them and what they did. It’s only an index of what remains of Carrie’s diaries, as recorded by Carrington and Rees. (We know a lot more about those people, places and things from, for example, Kipling’s published correspondence – but if they’re not in the diary extracts, then they won’t be found in this index.) Another factor is that both Carrington and Rees quite often mentions a name without further explanation or identification. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

Overruling Dred Scott: the Case for Same-Sex Marriage

OVERRULING DRED SCOTT: THE CASE FOR SAME-SEX MARRIAGE Robert A. Burt- Dred Scott v. Sandfordl is widely acknowledged to be the worst decision ever rendered by the United States Supreme Court. Its specific holdings-that Congress had no authority to regulate slavery in the territories and that no black person, whether slave or free, was a citizen of the United States entitled to bring suit in federal courts2-were overruled by the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments, enacted in the immediate wake of the Civil War. 3 But as we mark its 150th anniversary, it is not enough to say that the Dred Scott decision has been overruled. It is not enough to say that slavery has been abolished by the Thirteenth Amendment and that African Americans have been acknowledged as United States citizens by the Fourteenth Amendment. We must ask whether these two amendments, taken together, did more than overrule the specific holdings ofDred Scott. We must ask whether there was a deeper meaning to the reversal of this decision in order to determine whether the underlying assumptions ofDred Scott have truly been repudiated in our constitutional realm. In fact, the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments did more than simply overrule the specific substantive rulings in the Dred Scott case. The amendments were aimed, more fundamentally, at overruling the Supreme Court's underlying rationale for adopting these specific rules about slavery and black citizenship.4 This underlying rationale was stated by Chief Justice Taney in the following passage: black people, he said, were "beings of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the white race .. -

The Subject, Sitters, and Significance of the Arnolfini Marriage Portrait

Venezia Arti [online] ISSN 2385-2720 Vol. 26 – Dicembre 2017 [print] ISSN 0394-4298 Why Was Jan van Eyck here? The Subject, Sitters, and Significance of The Arnolfini Marriage Portrait Benjamin Binstock (Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, New York City, USA) Abstract Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Marriage Portrait of 1434 still poses fundamental questions. An overlooked account explained the groom’s left hand holding his bride’s right hand as a secular, legal morganatic marriage with a bride of lower social rank and wealth. That would explain Van Eyck’s presence as witness in the mirror and through his inscription, and corresponds to the recent identification of the bride and groom as Giovanni di Arrigo Arnolfini and his previously unknown first wife Helene of unknown last name. Van Eyck’s scene can be called the first modern painting, as the earliest autonomous, illusionistic representation of secular reality, provided with the earliest artist’s signature of the modern type, framing his scene as perceived and represented by a particular individual. That is why Jan van Eyck was here. Summary 1 What is being disguised: religious symbolism or secular art? – 2 A morganatic, left-handed marriage. – 3 The sitters: Giovanni di Arrigo Arnolfini and his first wife Helene? – 4 Van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait as the first modern painting. – 5 Van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait within his oeuvre and tradition. – 6 Van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait and art historical method. Keywords Jan van Eyck. Signature. Arnolfini. Morganatic Marriage. Modern painting. For Marek Wieczorek What is the hardest of all? What you think is the easiest. -

THE Sanfranciso CALL

Sporting and Automobile News Sporting and Automobile News Pages 40 to 45 THE San Francisco CALL Pages 40 to 45 . VOLUME CIX.—NO. 151. SAX FRANCISCO. SUNDAY, APRIL 30, 1911. PAGES 37 TO 48. Alleged Scandal Shown FOREIGN NEWS Work of Americans Is ENGLISH RULER Without Any Foundation CABLE Conspicuous in ItalyLABOR DISPLAY TORY PERSISTS WEDDING OF QUEEN VICTORIA’S NEPHEW LIBEL ON GEORGE V Whiskers Become Issue KING VICTOR OPENS IN LONG FIGHT BASIS FOR MISTAKEN ATTACK ON KING TRACED TO SOURCE In Society and Navy: TURIN EXHIBITION [Special Cable to The Call] }N^ Marriage LONDON, April 20.—WbJskera Story of Morganatic nave become |an I Issue of acute American Pavilion Contains the current interest through the " in- Due to Similarity of the dignant rebuke* that Captain Largest Display Ever Made ON HOME RULE Kdward Macllwalne of the. navy la \u25a0' engaged 'In 'heaping upon Women's Names RnKlUhnsen who do not .wear by Government Abroad them, In letters .to the ; London Palfour Continues Opposition to newspaper*. \u25a0 The burden of his attack* •\u25a0 \u25a0••!• that '/\u25a0 the ?. country'" manhood h«» become very low Biggest Attempted Lords' Veto Bill in Hope Daughter of Another Admiral when It Ignores the plain hints Affair in of two aovereiKnn, -the.< present Compromise Became Wife of Prince of kins- and hi* father, that Britons Italy Has Attractions From ?'•\u25a0' of should be bearded.' . Marllwalne himself sets an ex- Hohenlohe ample of the ! duty -of all . loyal AH Parts of World subjects by wearing; an enormous Emissaries Sent AllOver beard and Insisting that all | his Great staff .shall* cultivate - that adorn- TURIN", April 29.—The International By A. -

Unconventional Wisdom

Unconventional Wisdom A COMMONER’S TOUCH Kate Middleton’s dazzling social high-jump—from the pretty middle-class daughter of self-made millionaires to the future queen of England—is spectacular. But singular? Not really, says historian Amanda Foreman, who argues that Middleton’s climb to the top is actually part of a centuries-old—and very (gasp!) American—tradition. Illustration David Hughes For Americans, there is something undeniably Middleton may be the first British commoner to Alexander Baring, the first Baron Ashburton, familiar about Kate Middleton, the 29-year-old marry so spectacularly into the upper echelons in 1798. Bingham was the younger and pret- who, on April 29, will become the wife of Britain’s of British royalty, she is preceded by two centu- tier daughter of Senator William Bingham, Prince William. And although it’s partly her ries of American women who, armed only with the richest man in Pennsylvania and one of polished appearance—her perfect, impossibly their beauty, charm, and new money, periodi- the co-founders of the Bank of North America. straight white teeth and glossy hair—that strike cally sailed to England to find husbands—and By marrying the wildly ambitious Ashburton, a chord stateside, there’s something else about in doing so collectively helped save the nobility the head of Barings, Britain’s oldest merchant her that seems recognizable as well. from its own encroaching irrelevance. It’s some- bank, she was also responsible for the first So what is it? It’s not, of course, that Middleton thing that Middleton now has the chance to do transatlantic corporate merger. -

References to Morganatic Marriage in Some of the Pictorial Versions of the Marriage of Captain Martín De Loyola to Beatriz Ñusta

FORO Anales de Historia del Arte ISSN: 0214-6452 http://dx.doi.org/10.5209/ANHA.61619 References to Morganatic Marriage in some of the Pictorial Versions of The Marriage of Captain Martín de Loyola to Beatriz Ñusta Marina Mellado Corriente1 Recibido: 27 de noviembre de 2017 / Aceptado: 20 de junio de 2018 Abstract. A closer, and alternative, look at the set of colonial Peruvian paintings depicting the marriage of a Spanish captain and the Royal Governor of the Captaincy General of Chile to a princess, heiress to the deposed Inca throne, in 1572 reveals that while in the earliest known versions –created between 1675 and 1718– the groom firmly holds with his left hand the bride’s right hand, a later version, made around 1750, represents both spouses holding each other’s right hands. Morganatic marriages, or “marriages of the left hand,” were those celebrated between a privileged man and a woman of inferior status, and only rarely the other way around. In this study, certain iconographical aspects of four of the several pictorial versions known to once have existed, as well as the social, historical, and religious context in which they were created and exhibited, are analysed in detail, in order to suggest the hypothesis that the earliest pictorial interpretations of this celebrated alliance understood it intentionally as a morganatic union, with the goal of stressing the submission of the Andeans, especially of their elite –personified by the Inca princess– to the Christians, whereas a later representation interpreted it as a betrothal between equals, in order to convey that the indigenous elite had successfully come to perform a more prominent role in the colonial system. -

Marriage and Divorce Laws of the World

Marriage and Divorce Laws of the World Edited by HYACINTHE RINGROSE, D. C. L. Author of “The Inns of Court” “Marriage is the mother of the world, and preserves kingdoms, and fills cities, and churches, and heaven itself.”—Jeremy Taylor THE MUSSON-DRAPER COMPANY LONDON NEW YORK PARIS 1911 Copyright, 1911, by HYACINTHE RINGROSE All rights reserved [Pg 3] PREFACE The purpose of this volume is to furnish to the lawyer, legislator, sociologist and student a working summary of the marriage and divorce laws of the principal countries of the world. There are no geographical boundaries to virtue, wisdom and justice, and no country has as yet monopolized all that is best in creation. The mightiest of the nations lacks something which is possessed by the weakest; and there is no branch of comparative jurisprudence of more general consequence than that treating of marriage, which is the keystone of civilization. By “civilization” we do not mean community life according to the standard of a single individual or nation, but in its broader and better sense, meaning the civil organization of any large group of human beings. This book is not a brief in favour of, or against, any particular social system or legal code, nor has it a mission to assist in the reformation of any country’s marriage and divorce law. In the compilation which follows our endeavour is simply to set forth positive law as it exists to-day, leaving its correction or development to the proper authorities. The editor has lived among the books of the British Museum, the Bibliothèque Nationale and other great libraries for years, seeking in vain for just such a compilation as is here humbly presented. -

Literary Miscellany

Literary Miscellany Chiefly Recent Acquisitions. Catalogue 316 WILLIAM REESE COMPANY 409 TEMPLE STREET NEW HAVEN, CT. 06511 USA 203.789.8081 FAX: 203.865.7653 [email protected] www.williamreesecompany.com TERMS Material herein is offered subject to prior sale. All items are as described, but are considered to be sent subject to approval unless otherwise noted. Notice of return must be given within ten days unless specific arrangements are made prior to shipment. All returns must be made conscientiously and expediently. Connecticut residents must be billed state sales tax. Postage and insurance are billed to all non-prepaid domestic orders. Orders shipped outside of the United States are sent by air or courier, unless otherwise requested, with full charges billed at our discretion. The usual courtesy discount is extended only to recognized booksellers who offer reciprocal opportunities from their catalogues or stock. We have 24 hour telephone answering, and a Fax machine for receipt of orders or messages. Catalogue orders should be e-mailed to: [email protected] We do not maintain an open bookshop, and a considerable portion of our literature inventory is situated in our adjunct office and warehouse in Hamden, CT. Hence, a minimum of 24 hours notice is necessary prior to some items in this catalogue being made available for shipping or inspection (by appointment) in our main offices on Temple Street. We accept payment via Mastercard or Visa, and require the account number, expiration date, CVC code, full billing name, address and telephone number in order to process payment. Institutional billing requirements may, as always, be accommodated upon request. -

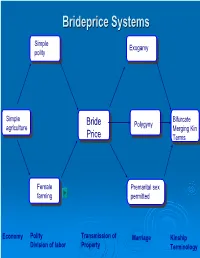

Brideprice Systemssystems

BridepriceBrideprice SystemsSystems Simple Exogamy polity Simple Bifurcate Bride Polygyny agriculture Merging Kin Price Terms Female Premarital sex farming permitted Economy Polity Transmission of Marriage Kinship Division of labor Property Terminology DowryDowry SystemsSystems Complex In-marriage polity Advanced Dowry Sibling agriculture Monogamy kin terms Male Prohibited farming premarital sex Economy Polity Transmission of Marriage Kinship Division of labor Property Terminology TheThe ValueValue ofof VirginityVirginity Economic None Bride Bride Gift Dowry Total Transaction Price Service Exchange & indirect dowry Virginity 31669 1852 valued Virginity 26 27 10 3 7 73 Virginity not valued N=125; Chi-square = 27.13; p<0.0001 Alice Schlegel, American Ethnologist, 18: 719-734 (1991) FemaleFemale ContributionsContributions toto PrimaryPrimary FoodFood ProductionProduction HHHH andand DD:DD: FurtherFurther ContrastsContrasts Bride Price Dowry Heir Production not relevant because of important because of lineal lateral inheritance inheritance and random demographic events Adoption by kin for care of parentless sometimes by kin for heir children production Non-reproductive rare spinsters and bachelors adults Alternative none concubines & morganatic marriage forms unions Marriage polygyny monogamy Gaining high status accumulation of human Accumulation of capital resources resources Divorce common rare Religious orders for absent present, celibates in non-reproductive religious order are celibates relatively common MorganaticMorganatic MarriageMarriage Etymology: New Latin matrimonium ad morganaticam, literally, marriage with morning gift Date: circa 1741 of, relating to, or being a marriage between a member of a royal or noble family and a person of inferior rank in which the rank of the inferior partner remains unchanged and the children of the marriage do not succeed to the titles, fiefs, or entailed property of the parent of higher rank. -

Edward VIII's Abdication and the Preservation of the British Monarchy

Salve Regina University Digital Commons @ Salve Regina Pell Scholars and Senior Theses Salve's Dissertations and Theses 12-2017 "Something Must Be Done!": Edward VIII's Abdication and the Preservation of the British Monarchy Allyse C. Zajac Salve Regina University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses Part of the European History Commons, and the Political History Commons Zajac, Allyse C., ""Something Must Be Done!": Edward VIII's Abdication and the Preservation of the British Monarchy" (2017). Pell Scholars and Senior Theses. 118. https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses/118 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Salve's Dissertations and Theses at Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pell Scholars and Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “SOMETHING MUST BE DONE!”: EDWARD VIII’S ABDICATION AND THE PRESERVATION OF THE BRITISH MONARCHY Allyse Zajac Salve Regina University Department of History Senior Thesis Dr. Leeman December 2017 Acknowledgements I would like to thank the McGinty family for creating the John E. McGinty Fund in History. Thanks to the John E. McGinty Fund, I was able to conduct research at both the Lambeth Palace Library and Parliamentary Archives in London. The documents I had access to at both of these archives have been fundamental to my research and I would not have had the opportunity to view them without the McGintys’ generosity. Zajac 1 To the average Englishman, 1936 appeared to be a good year.