Public Accounts Committee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Gd 2020/0058

GD 2020/0058 2020/21 1 Programme for Government October 2020 – July 2021 Introduction The Council of Ministers is pleased to bring its revised Programme for Government to Tynwald. The Programme for Government was agreed in Tynwald in January 2017, stating our strategic objectives for the term of our administration and the outcomes we hoped to achieve through it. As we enter the final year of this parliament, the world finds itself in the grip of the COVID-19 pandemic. This and other external factors, such as the prospect of a trade agreement between the UK and the EU, will undoubtedly continue to influence the work of Government in the coming months and years. What the Isle of Man has achieved over the past six months, in the face of COVID-19, has been truly remarkable, especially when compared to our nearest neighbours. The collective response of the people of our Island speaks volumes of the strength of our community and has served to remind us of the qualities that make our Island so special. At the beginning of the pandemic the Council of Ministers suspended the Programme for Government, and any work within it, to bring to bear the complete resources of the public service in the fight against coronavirus as we worked to keep our island and its people safe. Through the pandemic we have seen behaviour changes in society and in Government, and unprecedented times seem to have brought unprecedented ways of working. It is important for the future that we learn from the experiences of COVID and carry forward the positive elements of both what was achieved, and how Government worked together to achieve it. -

Up Close and Personal

www.business365iom.co.uk | OCTOBER 2020 ISSUE UP CLOSE AND PERSONAL WITH How one of the island’s leading Corporate Service Providers is putting people first FINANCIAL MAJOR ACQUISITION DAMNING INTELLIGENCE FOR STRIX REPORT The Isle of Man Financial Intelligence Unit Strix Group Plc, the Isle of Man-based leader in the An independent report commissioned by is among eight law enforcement agencies design, manufacture and supply of kettle safety government has described the Department of from smaller financial centres to be granted controls, has entered into a conditional agreement Education, Sport and Culture’s management, Associate Membership of the International to acquire the entire share capital of Italian water and its relationship with schools and teachers, Anti-Corruption Coordination Centre (IACC). purification business LAICA for approximately as fractured and in need of repair. €19.6m. THE ISLE OF MAN’S ONLY DEDICATED BUSINESS MAGAZINE NEWS | COMMENT | INSIGHT | PEOPLE | MOVEMENTS | FEATURES | TECHNOLOGY | HEALTH ProtectProtectProtectProtect youryouryouryour businessbusinessbusinessbusiness ProtectSecureProtectProtectSecureProtect offshoreoffshore youryour email,youryouremail, archivingarchiving && securitysecurity awarenessawareness businesstrainingbusinessbusinesstrainingbusiness servicesservices SecureSecure offshoreoffshore email,email, archivingarchiving && Inside securityInsidesecurity your your organisation organisation awarenessawareness ProtectProtectProtectProtectEducateEducate employees employees to to recognise recognise -

Bilateral Visit from Tynwald, Isle of Man 25 – 27 October 2017 Houses of Parliament, London

[insert map of the region] 1204REPORT/ISLEOFMAN17 Bilateral Visit from Tynwald, Isle of Man 25 – 27 October 2017 Houses of Parliament, London Final Report Contents About the Commonwealth Parliamentary Association UK ........................................................................................ 3 Summary ............................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Project Overview ............................................................................................................................................................. 5 Project Aim & Objectives ............................................................................................................................................... 5 Participants & Key Stakeholders ................................................................................................................................... 6 Key Issues .......................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Results of the Project ..................................................................................................................................................... 8 Next Steps ....................................................................................................................................................................... 10 Acknowledgements -

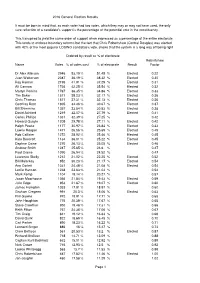

2016 General Election Statistics Summary

2016 General Election Results It must be born in mind that, as each voter had two votes, which they may or may not have used, the only sure reflection of a candidate's support is the percentage of the potential vote in the constituency. This transpired to yield the same order of support when expressed as a percentage of the entire electorate This tends to endorse boundary reforms but the fact that Chris Robertshaw (Central Douglas) was elected with 42% of the most popular LOSING candidate's vote, shows that the system is a long way off being right Ordered by result as % of electorate Robertshaw Name Votes % of votes cast % of electorate Result Factor Dr Alex Allinson 2946 53.19 % 51.45 % Elected 0.22 Juan Watterson 2087 36.19 % 38.32 % Elected 0.30 Ray Harmer 2195 41.91 % 37.29 % Elected 0.31 Alf Cannan 1736 42.25 % 35.54 % Elected 0.32 Martyn Perkins 1767 36.35 % 34.86 % Elected 0.33 Tim Baker 1571 38.23 % 32.17 % Elected 0.36 Chris Thomas 1571 37.31 % 32.13 % Elected 0.36 Geoffrey Boot 1805 34.46 % 30.67 % Elected 0.37 Bill Shimmins 1357 33.54 % 30.53 % Elected 0.38 David Ashford 1219 32.07 % 27.79 % Elected 0.41 Carlos Phillips 1331 32.39 % 27.25 % 0.42 Howard Quayle 1205 29.78 % 27.11 % Elected 0.42 Ralph Peake 1177 30.97 % 26.84 % Elected 0.43 Lawrie Hooper 1471 26.56 % 25.69 % Elected 0.45 Rob Callister 1272 28.92 % 25.46 % Elected 0.45 Kate Beecroft 1134 36.01 % 25.22 % Elected 0.45 Daphne Caine 1270 26.13 % 25.05 % Elected 0.46 Andrew Smith 1247 25.65 % 24.6 % 0.47 Paul Craine 1090 26.94 % 24.52 % 0.47 Laurence Skelly 1212 21.02 -

Actions Reporting

PROGRAMME FOR GOVERNMENT Q1 REPORTING 2019/20 DEPARTMENT ACTIONS 1 DEPARTMENT ACTIONS The Programme for Government ‘Our Island - a special place to live and work’ was approved by Tynwald in January 2017 and in April 2017 a performance framework, ‘Delivering a Programme for Government’, was also approved. The ‘Programme for Government 2016-21’ is a strategic plan that outlines measurable goals for Government. The Council of Ministers have committed to providing a public update against the performance framework on a quarterly basis. This report provides an update on performance through monitoring delivery of the actions committed to. The first quarter for 2019/20 ran April, May and June 2019. Information has been provided from across Government Departments, Boards and Offices, and the Cabinet Office have collated these to provide this report. The Programme for Government outlines a number of initial actions that were agreed by the Council of Ministers which will help take Government closer to achieving its overall objectives and outcomes. Departments Boards and Offices have developed action plans to deliver these actions and this report provides an update status report on delivery against these action plans. 2 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Lead Lead Sub Ref Action Comment Political Sponsor End Date 2018/19 2018/19 2018/19 2019/20 Department Committee We have an economy where local entrepreneurship is supported and thriving and more new businesses are choosing to call the Isle of Man home 1.1.01 Promote and drive the Enterprise This action was Department -

Year 4 Amendments

PROGRAMME FOR GOVERNMENT – YEAR 4 Updated 23/09/20 Programme for Government – Year 4 (October 2020 – July 2021) Actions to be removed We have an economy where local entrepreneurship is supported and thriving and more new businesses are choosing to call the Isle of Man home REF ACTION STATUS LEAD DEPARTMENT POLITICAL SPONSOR END DATE Form local development partnerships and produce local Replaced with 1.11 CABO Ray Harmer* Dec 2019 development plans 1.13 Secure a viable proposal for the redevelopment of the Replaced with 1.12 DOI Marlene Maska* April 2021 Summerland Site 1.13 We have a diverse economy where people choose to work and invest We have Island transport that meets our social and economic needs REF ACTION STATUS LEAD DEPARTMENT POLITICAL SPONSOR END DATE We have Island transport that meets our social and economic needs REF ACTION STATUS LEAD DEPARTMENT POLITICAL SPONSOR END DATE *Political Sponsor at the time the action was in progress 2 PROGRAMME FOR GOVERNMENT – YEAR 4 Updated 23/09/20 We have an education system which matches our skills requirements now and in the future REF ACTION STATUS LEAD DEPARTMENT POLITICAL SPONSOR END DATE 4.01 Introduce a regulatory framework for pre-school services Completed DESC Alex Allinson Dec 2021 4.02 Harmonise our further and higher education to ensure we Completed DESC Alex Allinson June 2018 achieve a more effective and value for money service We have an infrastructure which supports social and economic wellbeing REF ACTION STATUS LEAD DEPARTMENT POLITICAL SPONSOR END DATE Develop brownfield -

PROGRAMME for GOVERNMENT Q4 REPORTING Jan - Mar 2019/20 DEPARTMENT ACTIONS

PROGRAMME FOR GOVERNMENT Q4 REPORTING Jan - Mar 2019/20 DEPARTMENT ACTIONS Page 1 of 28 DEPARTMENT ACTIONS The Programme for Government ‘Our Island - a special place to live and work’ was approved by Tynwald in January 2017 and in April 2017 a performance framework, ‘Delivering a Programme for Government’, was also approved. The ‘Programme for Government 2016-21’ is a strategic plan that outlines measurable goals for Government. The Council of Ministers have committed to providing a public update against the performance framework on a quarterly basis. This report provides an update on performance through monitoring delivery of the actions committed to. The fourth and final quarter for 2019/20 ran January, February and March. Information has been provided from across Government Departments, Boards and Offices, and the Cabinet Office have collated these to provide this report on Key Performance Indicators. The Programme for Government outlines a number of initial actions that were agreed by the Council of Ministers which will help take Government closer to achieving its overall objectives and outcomes. Departments Boards and Offices have developed action plans to deliver these actions and this report provides an update status report on delivery against these action plans. Page 2 of 28 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Lead Ref Action Comment Political Sponsor End Date 2019/20 2019/20 2019/20 2019/20 Department We have an economy where local entrepreneurship is supported and thriving and more new businesses are choosing to call the Isle of Man 1.1.02 Partner -

2018-Nn-0012

Isle of Man Branch Report of the Chairman of the Branch Executive Committee for the period January 2017 to December 2017 Introduction 1. The aims of the Commonwealth Parliamentary Association are to promote knowledge of the constitutional, legislative, economic, social and cultural aspects of parliamentary democracy. It does this among other things by arranging Commonwealth Parliamentary Conferences, and other conferences, seminars, meetings and study groups; and by promoting visits between Members of the Branches of the Association. 2. This year saw the Isle of Man celebrate the 150th anniversary of the first popular election of the House of Keys, previously a self-elected body. 1867 was a date of pivotal significance in the advancement of Manx parliamentary democracy and a number of events took place to celebrate this anniversary in Manx political history. Farewells 3. 2017 saw the departure of just one CPA member: Mr Tony Wild was a member of the Legislative Council from 2011 to 2017 and an active member of the Isle of Man Branch. He represented the Isle of Man at regional conferences in Scotland in 2012 and the Falkland Islands in 2013, and attended a study visit to Westminster in 2012. On-Island activities in 2017 4. In February 2017 we were delighted to welcome Mr Akbar Khan, the Secretary- General of the Commonwealth Parliamentary Association, on his first visit to the Isle of Man, as part of a CPA parliamentary strengthening programme. During his visit Mr Khan delivered four CPA roadshows to schools in the Island, reaching more than 200 students; the roadshows focused on three core Commonwealth values - diversity, development and democracy. -

P R O C E E D I N G S

T Y N W A L D C O U R T O F F I C I A L R E P O R T R E C O R T Y S O I K O I L Q U A I Y L T I N V A A L P R O C E E D I N G S D A A L T Y N HANSARD Douglas, Tuesday, 4th October 2016 All published Official Reports can be found on the Tynwald website: www.tynwald.org.im/business/hansard Supplementary material provided subsequent to a sitting is also published to the website as a Hansard Appendix. Reports, maps and other documents referred to in the course of debates may be consulted on application to the Tynwald Library or the Clerk of Tynwald’s Office. Volume 134, No. 1 ISSN 1742-2256 Published by the Office of the Clerk of Tynwald, Legislative Buildings, Finch Road, Douglas, Isle of Man, IM1 3PW. © High Court of Tynwald, 2016 TYNWALD COURT, TUESDAY, 4th OCTOBER 2016 Present: The President of Tynwald (Hon. S C Rodan) In the Council: The Lord Bishop of Sodor and Man (The Rt Rev. R M E Paterson), The Acting Attorney General (Mr J L M Quinn), Mr D M Anderson, Mr M R Coleman, Mr C G Corkish MBE, Mr D C Cretney, Hon. T M Crookall, Mr R W Henderson, Mr J R Turner and Mr T P Wild, with Mr J D C King, Deputy Clerk of Tynwald. In the Keys: The Speaker (Hon. -

Tynwald Annual Report 2019/2020 Engage with Tynwald on Twitter @Tynwaldinfo

PP 2020/0187 Tynwald Annual Report Parliamentary Year 2019/2020 Tynwald Annual Report 2019/2020 Engage with Tynwald on Twitter @tynwaldinfo Get live updates during Tynwald sittings from @tynwaldlive We hope you will find this report useful. If you would like to comment on any aspect of it, please contact: The Clerk of Tynwald Office of the Clerk of Tynwald Legislative Buildings Finch Road Douglas Isle of Man IM1 3PW Telephone: +44 (0)1624 685500 Email: [email protected] An electronic copy of this report can be found at: http://www.tynwald.org.im/bu siness/pp/Reports/2020-PP-187 Tynwald Annual Report 2019/2020 Contents Page 2 Foreword 3 The Isle of Man and COVID-19 4 Changes in Membership 9 The Work of Legislature 18 Tynwald Day 2020 23 Inter Parliamentary Engagement 29 Education and Outreach 31 The Office of the Clerk of Tynwald 3 Tynwald Annual Report 2019/2020 Tynwald Annual Report 2019/2020 Foreword President of Tynwald Speaker of the House of Keys The Hon. Stephen Charles Rodan The Hon. Juan Paul Watterson BA OBE Bsc (Hons) MRPharmS MLC (Hons) BFP FCA CMgr FCMI FRSA SHK This has been a particularly difficult year. Political life was, of course, dominated in spring and early summer by the ravages of the COVID-19 pandemic, as in the rest of the world. We have been lucky in the Isle of Man that we have been spared some of the worst impact of this terrible disease; our hearts go out to those people who have lost loved ones or experienced the dangers and discomforts which the virus can bring. -

Hansard Business Search Template

4. Nomination of Chief Minister – Mr Howard Quayle elected In accordance with section 2 of the Council of Ministers Act 1990, to nominate one Member of Tynwald for appointment as Chief Minister. The Members proposed for nomination are: Mrs K J Beecroft Mr A L Cannan Hon R H Quayle The President: Hon. Members, we now turn to our Order Paper. The main business of today is the election of a Chief Minister. This election is governed by section 2 of the Council of Ministers Act 1990 and also by Standing Orders 1.5, 2.4A, 3.17A and 5.3, as amended by the recent change to Standing Orders, Standing Order 3.17B. Three members have been proposed: Mrs Kate Beecroft, proposed by Mr Lawrie Hooper and seconded by Ms Julie Edge; Mr Alfred Cannan, proposed by Mr Chris Thomas and seconded by Mr Martyn Perkins; and Mr Howard Quayle, proposed by Mr David Ashford and seconded by Mr Ray Harmer. I intend to take the nominations in alphabetical order of the nominees. I will therefore invite the proposer and seconder of the nomination of the Hon. Member for Douglas South, Mrs Beecroft, followed by the proposer and seconder of the nomination of the Hon. Member for Ayre and Michael, Mr Cannan, and then the Hon. Member for Middle, Mr Quayle. Following established practice, I shall allow Hon. Members’ proposing and seconding nominees to speak in support of that nominee, but I shall not allow other speeches. I remind Hon. Members of the procedure which is in two parts. -

Political Roles and Responsibilities - PAY Page 2

PP 2019/0158 EMOLUMENTS OF MEMBERS OF TYNWALD REPORT BY AN INDEPENDENT PANEL NOVEMBER 2019 To: Standing Committee of Tynwald on Emoluments You appointed us earlier this year to review the Emoluments of Members of Tynwald. We now present our Report to you. Should you wish to publish our Report, we would have no objection. Ian Cochrane (Chair) Jennifer Houghton Sir Miles Walker Douglas 18th November 2019 I. Tynwald, its Members, what they do, and how they are paid ........................................1 II. The review ........................................................................................................................2 III. Overall costs .....................................................................................................................3 IV. Level of pay.......................................................................................................................3 V. Executive and scrutiny roles.............................................................................................4 VI. The civil service link..........................................................................................................6 VII. Expenses...........................................................................................................................6 VIII. Differential between the Branches ..................................................................................7 IX. Pensions............................................................................................................................9