Bassetlaw Open Data

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

And an Invitation to Help Us Preserve

HISTORICAL NOTES CONT’D (3) ST.NICHOLAS, ICKFORD. This and other Comper glass can be recognised by a tiny design of a strawberry plant in one corner. Vernon Stanley HISTORICAL NOTES ON OUR is commemorated in the Comper window at the end of GIFT AID DECLARATION the south aisle, representing St Dunstan and the Venerable WONDERFUL CHURCH Bede; the figure of Bede is supposed to have Stanley’s Using Gift Aid means that for every pound you features. give, we get an extra 28 pence from the Inland Revenue, helping your donation go further. AN ANCIENT GAME On the broad window sill of the triple window in the north aisle is scratched the frame for This means that £10 can be turned in to £12.80 a game played for many centuries in England and And an invitation to help us just so long as donations are made through Gift mentioned by Shakespeare – Nine Men’s Morris, a Aid. Imagine what a difference that could make, combination of the more modern Chinese Chequers and preserve it. and it doesn’t cost you a thing. noughts and crosses. It was played with pegs and pebbles. GILBERT SHELDON was Rector of Ickford 1636- So if you want your donation to go further, Gift 1660 and became Archbishop of Canterbury 1663-1677. Aid it. Just complete this part of the application The most distinguished person connected with this form before you send it back to us. church, he ranks amongst the most influential clerics to occupy the see of Canterbury. He became a Rector here a Name: __________________________ few years before the outbreak of the civil wars, and during that bad and difficult time he was King Charles I’s trusted Address: ____________________ advisor and friend. -

Holy Trinity Church Parish Profile 2018

Holy Trinity Church Headington Quarry, Oxford Parish Profile 2018 www.hthq.uk Contents 4 Welcome to Holy Trinity 5 Who are we? 6 What we value 7 Our strengths and challenges 8 Our priorities 9 What we are looking for in our new incumbent 10 Our support teams 11 The parish 12 The church building 13 The churchyard 14 The Vicarage 15 The Coach House 16 The building project 17 Regular services 18 Other services and events 19 Who’s who 20 Congregation 22 Groups 23 Looking outwards 24 Finance 25 C. S. Lewis 26 Community and communications 28 A word from the Diocese 29 A word from the Deanery 30 Person specification 31 Role description 3 Welcome to Holy Trinity Thank you for looking at our Are you the person God is calling Parish Profile. to help us move forward as we seek to discover God’s plan and We’re a welcoming, friendly purposes for us? ‘to be an open door church on the edge of Oxford. between heaven and We’re known as the C. S. Lewis Our prayers are with you as you earth, showing God’s church, for this is where Lewis read this – please also pray for worshipped and is buried, and us. love to all’ we also describe ourselves as ’the village church in the city’, because that’s what we are. We are looking for a vicar who will walk with us on our Christian journey, unite us, encourage and enable us to grow and serve God in our daily lives in the parish and beyond. -

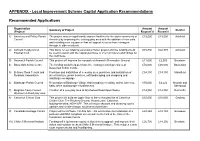

APPENDIX - Local Improvement Scheme Capital Application Recommendations

APPENDIX - Local Improvement Scheme Capital Application Recommendations Recommended Applications Organisation Amount Amount Summary of Project District (Project) Request’d Recom’d 1) Annesley and Felley Parish The project aims to significantly improve facilities for the wider community of £19,500 £19,500 Ashfield Council Annesley by improving the existing play area with the addition of new units and installing new equipment that will appeal to users from teenagers through to older residents. 2) Ashfield Rugby Union This bid is for our 'Making Larwood a Home' project and the funding would £45,830 £22,915 Ashfield Football Club be used to assist with the capital purchase of internal fixtures and fittings for the clubhouse. 3) Awsworth Parish Council This project will improve the car park at Awsworth Recreation Ground. £11,000 £2,000 Broxtowe 4) Bassetlaw Action Centre The funding would help purchase the existing (rented) premises at £50,000 £20,000 Bassetlaw Bassetlaw Action Centre. 5) Bellamy Road Tenant and Provision and installation of new play area, purchase and installation of £34,150 £34,150 Mansfield Resident Association street furniture, picnic benches, soft landscaping and designing and installing new signage 6) Bilsthorpe Parish Council Restoration of Bilsthorpe Village Hall including re-roofing, toilets, kitchens, £50,000 £2,222 Newark and halls, office and storage refurbishment. Sherwood 7) Bingham Town Council Creation of a new play area at Wychwood Road Open Space. £14,950 £14,950 Rushcliffe Wychwood Road play area 8) Calverton Cricket Club This project will build an upper floor to the cricket pavilion at Calverton £35,000 £10,000 Gedling Cricket Club, The Rookery Ground, Woods Lane, Calverton, Nottinghamshire, NG14 6FF. -

Ashfield District Council

Dear sir/madam, 1 - Could you please confirm if you have carried out the compounding of any recycling banks belonging to 3rd parties promoting textile and or shoe recycling? 2 - if answer to (1) above is yes, could you confirm if you hold these containers in storage? Thank you for your Freedom of Information Request. The response from the department is as follows: These recycling banks are not normally on the adopted highway , and usually in supermarket car parks or on Borough or District Council Land. There used to be these ones, but they were taken out by the borough council years ago - https://goo.gl/maps/78cbiBF1Yei7v9mFA I would suggest that the District & Borough Councils may be able to provide you with further information, you can contact them at the following addresses: Ashfield District Council: [email protected] Bassetlaw District Council: [email protected] Broxtowe Borough Council: [email protected] Gedling Borough Council: [email protected] Mansfield District Council: [email protected] Newark & Sherwood District: [email protected] Rushcliffe Borough Council: [email protected] Nottingham City Council: [email protected] I hope this now satisfies your request, and should you have any further enquiries please do not hesitate to contact me directly on the details below. In addition to this and for future reference Nottingham County Council regularly publishes previous FOIR,s and answers on its website, under Disclosure logs. (see link) http://site.nottinghamshire.gov.uk/thecouncil/democracy/freedom-of-information/disclosure-log/ You can use the search facility using keywords. -

[email protected]

email: [email protected] THE SHERWOOD RANGERS YEOMANRY REGIMENTAL ASSOCIATION From: Capt MA Elliott Hon Secretary 26th February 2019 Dear Member, AGM and ANNUAL DINNER - Saturday 13 th April 2019 This year's Annual Reunion Dinner will be held at 6.30 for 7.00pm on Saturday 13 th April at the Army Reserve Centre, Carlton, by kind permission of the Squadron Leader, Major Simon Hallsworth. The cost of the Dinner will be £28 per person to include wine and port. The South Notts Hussars Band will play during the meal. Full details are enclosed on a separate sheet. I hope that as many members as possible will attend. Please apply to me (or to the SSM if you are a serving member) in good time. If you apply to me please use the correct form (attached). We will always try to accommodate latecomers but if a large number of people turn up at the last minute it makes life very difficult for the organisers. Guests are welcome at the dinner but must be connected with the SRY or other regiments. Serving members of A Sqn should, as usual, obtain their dinner tickets from the Squadron. However, if you put your name on the Squadron list, please do not order a ticket from me as well or you will have to pay twice. Display Board. At the dinner we plan to have a pop-up photo display for photos of the SRY through the years so please bring along pictures of your service for the display . Raffle. At the Dinner, we shall again be holding a raffle and any donations of prizes will be gratefully received. -

Pupils with Special Educational Needs (SEN) in Nottinghamshire Schools by the School They Attend Data Source: Jan 2018 School Census

Pupils with special educational needs (SEN) in Nottinghamshire schools by the school they attend Data source: Jan 2018 school census DfE ID Name District Phase SEN Pupils 2788 Abbey Gates Primary School Gedling Primary 7 3797 Abbey Hill Primary School Ashfield Primary 39 3297 Abbey Primary School Mansfield Primary 33 2571 Abbey Road Primary School Rushcliffe Primary 17 2301 Albany Infant and Nursery School Broxtowe Primary 8 2300 Albany Junior School Broxtowe Primary 9 2302 Alderman Pounder Infant School Broxtowe Primary 24 4117 Alderman White School Broxtowe Secondary 58 3018 All Hallows CofE Primary School Gedling Primary 21 4756 All Saints Catholic Voluntary Academy Mansfield Secondary 99 3774 All Saints CofE Infants School Ashfield Primary 9 3539 All Saints Primary School Newark Primary x 2010 Annesley Primary and Nursery School Ashfield Primary 29 3511 Archbishop Cranmer Church of England Academy Rushcliffe Primary 5 2014 Arnbrook Primary School Gedling Primary 29 2200 Arno Vale Junior School Gedling Primary 8 4091 Arnold Hill Academy Gedling Secondary 89 2916 Arnold Mill Primary School Gedling Primary 61 2942 Arnold View Primary and Nursery School Gedling Primary 35 7023 Ash Lea School Rushcliffe Special 74 4009 Ashfield School Ashfield Secondary 291 3782 Asquith Primary and Nursery School Mansfield Primary 52 3783 Awsworth Primary School Broxtowe Primary 54 2436 Bagthorpe Primary School Ashfield Primary x 2317 Banks Road Infant School Broxtowe Primary 18 2921 Barnby Road Academy Primary & Nursery School Newark Primary 71 2464 Beardall -

1 East Midlands Scrutiny Network Meeting 1 July 2016 Attendees

East Midlands Scrutiny Network Meeting 1 July 2016 Attendees Bassetlaw District Council Cllr Madeline Richardson, Vanessa Cookson Blaby District Council Cllr David Jennings, Cllr Les Philimore Charnwood Borough Council/Leicestershire CC Cllr Richard Shepherd East Midlands Councils Kirsty Lowe Erewash Borough Council Angela Taylor, Angelika Kaufhold Gedling Borough Council Helen Lee, Cllr Meredith Lawrence Leicester City Council Jerry Connolly Lincolnshire County Council Nigel West Northamptonshire County Council Cllr Allen Walker, James Edmunds Nottingham City Council Cllr Glynn Jenkins, Rav Kalsi Apologies Blaby District Council Linda McBean Charnwood Borough Council Michael Hopkins Chesterfield Borough Council Cllr Tricia Gilby, Anita Cunningham Corby Borough Council Cllr Judy Caine Daventry District Council Cllr Colin Morgan East Northamptonshire Council Cllr Jake Vowles Leicester City Council Alex Sargeson City of Lincoln Council Cllr Jackie Kirk North East Derbyshire District Council Cllr Tracy Reader, Sarah Cottam Notes Welcome and introductions Cllr Walker welcomed network members and thanked Nottingham City Council for hosting the network meeting. Minutes from the Last meeting The minutes from the last network meeting were agreed. Impact of Gambling on Vulnerable Communities…. A Review Cllr Walker welcomed Jerry Connelly from Leicester City and thanked him for agreeing to present on the recent review of Gambling at Leicester City Council. The presentation covered; Context and structure of Scrutiny at Leicester City Council and -

SCRUTINY NETWORK Friday 1 February 2019, 10:00 – 12:30

SCRUTINY NETWORK Friday 1 February 2019, 10:00 – 12:30 Rutland County Council Attendees Blaby District Council Linda McBean Bolsover District Council Joanne Wilson Bolsover District Council Cllr Karl Reid Charnwood Borough Council Michael Hopkins Chesterfield Borough Council Amanda Clayton Chesterfield Borough Council Rachel Appleyard Chesterfield Borough Council Cllr Kate Sarvent East Midlands Councils Kirsty Lowe Erewash Borough Council Angelika Kaufhold Gedling Borough Council Cllr Marje Paling Lincolnshire County Council Nigel West Northampton Borough Council Cathrine Russell Northampton Borough Council Tracy Tiff Rutland County Council Natasha Taylor Rutland County Council Jo Morley University of Birmingham John Cade Apologies Bassetlaw District Council Richard Gadsby Bassetlaw District Council Cllr John Shepherd Blaby District Council Suraj Savant Chesterfield Borough Council Cllr Peter Innes Gedling Borough Council Helen Lee Hinckley and Bosworth Borough Council Rebecca Owen Kettering Borough Council Cllr Mick Scrimshaw Northampton Borough Council Cllr Graham Walker South Northamptonshire and Cherwell Emma Faulkner South Northamptonshire and Cherwell Lesley Farrell South Northamptonshire and Cherwell Natasha Clark Notes Welcome from Cllr Karl Reid, Chair of the East Midlands Scrutiny Network Cllr Karl Reid welcomed network members to Oakham and thanked Rutland County Council for hosting the network meeting. Minutes from the last meeting The minutes of the last meeting were agreed. CfPS Scrutiny Guidance Workshop John Cade from the Institute of Local Government Studies at the University of Birmingham provided an overview of the recent Centre for Public Scrutiny workshop on the Government guidance that is due to be published in the coming weeks. John provided an update on the guidance and the journey so far, from the initial Select Committee review into Local Government Overview and Scrutiny. -

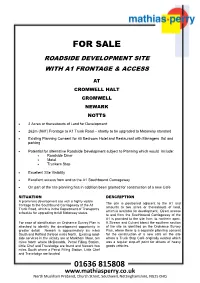

Roadside Development Site with A1 Frontage & Access

FOR SALE ROADSIDE DEVELOPMENT SITE WITH A1 FRONTAGE & ACCESS AT CROMWELL HALT CROMWELL NEWARK NOTTS • 2 Acres or thereabouts of Land for Development • 262m (860’) Frontage to A1 Trunk Road – shortly to be upgraded to Motorway standard • Existing Planning Consent for 40 Bedroom Hotel and Restaurant with Managers flat and parking • Potential for alternative Roadside Development subject to Planning which would include: • Roadside Diner • Motel • Truckers Stop • Excellent Site Visibility • Excellent access from and to the A1 Southbound Carriageway • On part of the site planning has in addition been granted for construction of a new Cafe SITUATION DESCRIPTION A prominent development site with a highly visible The site is positioned adjacent to the A1 and frontage to the Southbound Carriageway of the A1 amounts to two acres or thereabouts of land, Trunk Road, which is in the Department of Transport’s which is available for development. Direct access schedule for upgrading to full Motorway status. to and from the Southbound Carriageway of the A1 is provided to the site from its northern apex. For ease of identification an Ordnance Survey Plan is A Stream and Culvert bisect the southern section attached to identify the development opportunity in of the site as identified on the Ordnance Survey greater detail. Newark is approximately six miles Plan, where there is a separate planning consent South and Retford thirteen miles North. Existing road- for the construction of a new café on the site side services in the vicinity are at Markham Moor, ten where a Truck Stop Café originally existed which miles North where McDonalds, Petrol Filling Station, was a regular stop-off point for drivers of heavy Little Chef and Travelodge are found and Newark two goods vehicles. -

Worksop to Nottingham Retford to Nottingham Connecting at New Ollerton Connecting at New Ollerton

Worksop to Nottingham Retford to Nottingham connecting at New Ollerton connecting at New Ollerton Worksop to New Ollerton Retford to New Ollerton showing connections for S h e r w o o d Arrow showing connections for S h e r w o o d Arrow New Ollerton to Nottingham New Ollerton to Nottingham Monday to Saturday except Bank Holidays Monday to Saturday except Bank Holidays journey codes MF MF MF S G journey codes SD L SSH Worksop Hardy Street 0540 0640 0720 0730 0815 0940 1140 1340 1515 1740 2120 Retford Bus Station 0615 0730 0745 1015 1215 1415 1645 1815 Worksop Town Hall 0543 0643 0723 0733 0818 0943 1143 1343 1518 1743 2125 Retford Rail Station 0619 0734 0749 1019 1219 1419 1649 1819 Carburton Crossroads 0551 0651 0731 0741 0826 0951 1151 1351 1526 1751 2133 Ordsall West Hill Road 0623 0738 0753 1023 1223 1423 1653 1823 Budby Village 0554 0654 0734 0744 0829 0954 1154 1354 1529 1754 2136 Markham Moor Great North Rd 0630 0745 0800 1030 1230 1430 1700 1830 New Ollerton Briar Road 0600 0700 0740 0750 0835 1000 1200 1400 1535 1800 2140 Tuxford Sun Inn 0644 0759 0814 1044 1244 1444 1714 1844 Kirton 0651 -- 0821 1051 1251 1451 1721 1851 New Ollerton Briar Road 0605 -- 0745 -- -- 1005 1205 1405 1550 1805 2145 New Ollerton Briar Road 0700 0830 0830 1100 1300 1500 1730 1900 Old Ollerton Hop Pole 0608 -- 0748 -- -- 1008 1208 1408 1553 1808 2148 Sherwood Forest Visitor Centre -- -- -- -- -- 1018 1218 1418 -- -- -- New Ollerton Briar Road 0705 0835 0835 1105 1305 1505 1735 -- Edwinstowe High Street 0613 -- 0753 -- -- 1020 1220 1420 -- 1812 2152 Old -

The Jesse Tree Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE JESSE TREE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Geraldine Mccaughrean | 96 pages | 21 Nov 2006 | Lion Hudson Plc | 9780745960760 | English | Oxford, United Kingdom The Jesse Tree PDF Book First Name. We cannot do it without your support. Many of the kings who ruled after David were poor rulers. As a maximum, if the longer ancestry from Luke is used, there are 43 generations between Jesse and Jesus. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Quite possibly this is also the forerunner of our own Christmas tree. The tree itself can be one of several types. The tree with five undulating branches carved in foliage rises from the sculptured recumbent form of Jesse. In the picture, the prophet Isaiah approaches Jesse from beneath whose feet is springing a tree, and wraps around him a banner with words upon it which translate literally as:- "A little rod from Jesse gives rise to a splendid flower", following the language of the Vulgate. Several 13th-century French cathedrals have Trees in the arches of doorways: Notre-Dame of Laon , Amiens Cathedral , and Chartres central arch, North portal - as well as the window. Jesus was a descendent of King David and Christians believe that Jesus is this new branch. I am One in a Million. Monstrance from Augsburg A late 17th-century monstrance from Augsburg incorporates a version of the traditional design, with Jesse asleep on the base, the tree as the stem, and Christ and twelve ancestors arranged around the holder for the host. Sometimes this is the only fully illuminated page, and if it is historiated i. -

![Complete Baronetage of 1720," to Which [Erroneous] Statement Brydges Adds](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5807/complete-baronetage-of-1720-to-which-erroneous-statement-brydges-adds-845807.webp)

Complete Baronetage of 1720," to Which [Erroneous] Statement Brydges Adds

cs CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND GIVEN IN 1891 BY HENRY WILLIAMS SAGE CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 3 1924 092 524 374 Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/cletails/cu31924092524374 : Complete JSaronetage. EDITED BY Gr. Xtl. C O- 1^ <»- lA Vi «_ VOLUME I. 1611—1625. EXETER WILLIAM POLLAKD & Co. Ltd., 39 & 40, NORTH STREET. 1900. Vo v2) / .|vt POirARD I S COMPANY^ CONTENTS. FACES. Preface ... ... ... v-xii List of Printed Baronetages, previous to 1900 xiii-xv Abbreviations used in this work ... xvi Account of the grantees and succeeding HOLDERS of THE BARONETCIES OF ENGLAND, CREATED (1611-25) BY JaMES I ... 1-222 Account of the grantees and succeeding holders of the baronetcies of ireland, created (1619-25) by James I ... 223-259 Corrigenda et Addenda ... ... 261-262 Alphabetical Index, shewing the surname and description of each grantee, as above (1611-25), and the surname of each of his successors (being Commoners) in the dignity ... ... 263-271 Prospectus of the work ... ... 272 PREFACE. This work is intended to set forth the entire Baronetage, giving a short account of all holders of the dignity, as also of their wives, with (as far as can be ascertained) the name and description of the parents of both parties. It is arranged on the same principle as The Complete Peerage (eight vols., 8vo., 1884-98), by the same Editor, save that the more convenient form of an alphabetical arrangement has, in this case, had to be abandoned for a chronological one; the former being practically impossible in treating of a dignity in which every holder may (and very many actually do) bear a different name from the grantee.