The Laws and Customs of Anglo-American Whaling, 1780-1880

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Japanese Whaling and the International Community: Enforcing the International Court of Justice and Halting NEWREP-A

Japanese Whaling and the International Community: Enforcing the International Court of Justice and Halting NEWREP-A By Samuel K. Rebmann The bodies that regulate public international law, particularly those concerning areas of environmental law, are currently incapable of unilaterally enforcing international treaties and conventions. On December 1, 2015, Japan’s Institute of Cetacean Research (ICR) commenced the organization’s New Scientific Whale Research Program in the Antarctic Ocean (NEWREP-A). This paper argues that by launching NEWREP-A, Japan willfully acted in direct contravention to the International Court of Justice’s ruling in Australia v. Japan (2014), which found that the ICR’s previous research programs violated existing public international law and, thus, blocked all future scientific whaling permits from being issued to the Japanese institute. Through examining the international treaties and conventions governing whaling, environmental and maritime law, the historical context of Japanese whaling practices, and American legislative and political history, this paper defends the International Court of Justice’s opinion and calls on the American government to support and enforce the ruling through extraterritorial application of United States law. In direct opposition to a 2014 ruling by the International Court of Justice (ICJ), the Japanese government declared in June 2015 their intent to revive the Institute of Cetacean Research’s (ICR) scientific whaling program. The ICJ held in Australia v. Japan that the second phase of the Japanese Whale Research Program Under Special Permit in the Antarctic (JARPA II) violated international law; the court ordered the revocation of all existing permits and prevented the issuance of future permits, which included the proposed Research Plan for New Scientific Whale Research Program in the Antarctic Ocean (NEWREP-A).¹ Specifically, the court found that JARPA II failed to observe regulations set forth by the International Whaling Commission (IWC), such as the 1986 binding international moratorium 1. -

Modern Whaling

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: In Pursuit of Leviathan: Technology, Institutions, Productivity, and Profits in American Whaling, 1816-1906 Volume Author/Editor: Lance E. Davis, Robert E. Gallman, and Karin Gleiter Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBN: 0-226-13789-9 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/davi97-1 Publication Date: January 1997 Chapter Title: Modern Whaling Chapter Author: Lance E. Davis, Robert E. Gallman, Karin Gleiter Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c8288 Chapter pages in book: (p. 498 - 512) 13 Modern Whaling The last three decades of the nineteenth century were a period of decline for American whaling.' The market for oil was weak because of the advance of petroleum production, and only the demand for bone kept right whalers and bowhead whalers afloat. It was against this background that the Norwegian whaling industry emerged and grew to formidable size. Oddly enough, the Norwegians were not after bone-the whales they hunted, although baleens, yielded bone of very poor quality. They were after oil, and oil of an inferior sort. How was it that the Norwegians could prosper, selling inferior oil in a declining market? The answer is that their costs were exceedingly low. The whales they hunted existed in profusion along the northern (Finnmark) coast of Norway and could be caught with a relatively modest commitment of man and vessel time. The area from which the hunters came was poor. Labor was cheap; it also happened to be experienced in maritime pursuits, particularly in the sealing industry and in hunting small whales-the bottlenose whale and the white whale (narwhal). -

Whale Species

Whale鯨の種類 species Whales are grouped as baleen whales (14 species) or toothed whales (70 species). Baleen whales have baleen plates in the upper jaws and two blowholes on the top of their heads. Toothed whales bear teeth and a single blowhole. Dolphins and porpoises are whales below 4 meters in length. Baleen whale examples Blue whale Bryde’s whale Fin whale Sei whale Humpback whale Minke whale Antarctic minke whale Bowhead whale Gray whale Toothed whale examples Beluga Sperm whale Pilot whale Killer whale Bottlenose dolphin Baird’s beaked whale Origin of the term "kujira" (whale) Although there is no definite etymology for the Japanese word for whale (“kujira”), according to one theory, since whales have big mouths, “kujira” was derived from the term “kuchihiro” (wide mouth). It is also said that in ancient Korean language, the particle “ku” meant big size, “shishi” indicated a beast or animal, and “ra” represented a postfix; the term “kushirara” shortened to “kujira”. The kanji character representing “kujira” means big fish. Another term used in Japan for whale is “isana” and is usually written with the two kanji characters indicating “brave fish”. In the Manyoshu, the oldest existing collection of Japanese poetry, the term “isanatori” (whale hunter) was used as a customary epithet in sea-related context. It is also said that the term “isana” has its origins in the ancient Korean language, meaning “big fish”. Reference: Kujira to Nihon-jin (Seiji Ohsumi, Iwanami Shincho). 1 What is the IWC? IWC Organization The International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling (ICRW) was concluded International Whaling in 1946. -

By ROBERT F. HEIZER

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 133 Anthropological Papers, No. 24 Aconite Poison Whaling in Asia and America An Aleutian Transfer to the New World By ROBERT F. HEIZER 415 . CONTENTS PAGE Introduction 419 Kamchatka Peninsula-Kurile Islands 421 Japan 422 Koryak 425 Chukchee 426 Aleutian Islands 427 Kodiak Island region 433 Eskimo 439 Northwest Coast 441 Aconite poison 443 General implications of North Pacific whaling 450 Appendix 1 453 The use of poison-harpoons and nets in the modern whale fishery 453 The modern use of heavy nets in whale catching 459 Bibliography 461 ILLUSTRATIONS PLATES 18. The whale fishery of the Greenland Eskimo 468 19. Greenland whales and harpoon with bladder 468 20. Cutting up the whale, Japan 468 21. Dispatching the already harpooned and netted whale with lances, Japan 468 22 Japanese whalers setting out nets for a whale 468 23. The whale hunt of the Aleuts 468 23a. Whale hunt of the Kodiak Island natives (after de Mofras) 468 TEXT FIGURES 56 Whaling methods in the North Pacific and Bering Sea (map) 420 57. Whaling scenes as represented by native artists 423 58. Whaling scenes according to native Eskimo artists 428 59 South Alaskan lance heads of ground slate 432 60. Ordinary whale harpoon and poison harpoon with hinged barbs 455 417 ACONITE POISON WHALING IN ASIA AND AMERICA AN ALEUTIAN TRANSFER TO THE NEW WORLD By Robert F. Heizer INTRODUCTION In this paper I propose to discuss a subject which on its own merits deserves specific treatment, and in addition has the value of present- ing new evidence bearing on the important problem of the interchange of culture between Asia and America via the Aleutian Island chain. -

Japan, the West, and the Whaling Issue: Understanding the Japanese Side

Routledge Taylor & Fronds CroL Japaiij the West^ and the whaling issue: understanding the Japanese side AMY L. CATALINAC AND GERALD CHAN Abstract: This article examines the current dispute over whaling from the per- spective of Japan, a country that is fiercely protective of its right to whale. It outlines the key role played by transnational environmental actors in defining and instituting an international norm of anti-whaling, symbolized in the passage of the moratorium on commercial whaling in 1982. This signalled a rejection of previously held attitudes towards the use of whales as natural resources and the embracing of a protectionist, hands-off approach. Support for this new stance however was not forthcoming from pro-whaling states Japan, Norway and Iceland. By analysing Japan's original objection to the moratorium, its later compliance and its commitment to the resumption of limited commercial whaling, this article outlines the principles that underpin Japan's whaling policy. While the Japanese government views the whaling dispute as a threat to resource security and also a danger to inter-state respect for differences in custom and cuisine, the need to be perceived as a responsible member of international society exercises a major influence on the formation of Japan's whaling policy, conditioning its rule compli- ance and prohibiting the independent action pursued by other pro-whaling states. Recent developments in the whaling dispute, however, may be enough to dislodge Japan's commitment to the moratorium, which would impact upon the legitimacy of the International Whaling Commission itself. Keywords: Japanese whaling, international norms, rule compliance, environ- mental movements, international legitimacy Introduction During the meeting of the International Whaling Commission each year, con- siderable outrage is directed towards Japan by anti-whaling countries and envi- ronmental non-governmental organizations for its desire to hunt and eat whales. -

University of Groningen Arctic Whaling Jacob, H.K. S'; Snoeijing, K

University of Groningen Arctic whaling Jacob, H.K. s'; Snoeijing, K Published in: EPRINTS-BOOK-TITLE IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 1984 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Jacob, H. K. S., & Snoeijing, K. (1984). Arctic whaling: proceedings of the International Symposium Arctic Whaling February 1983. In EPRINTS-BOOK-TITLE (8 ed.). s.n.. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 25-09-2021 HISTORICAL SURVEY OF THE EUROPEAN WHALING INDUSTRY by Richard Vaughan Defining the Arctic is not just a question oflatitude. Southampton Island in the north of Hudson Bay, surrounded by ice in winter and the centre of a historic Arctic whale fishery, is in the same latitude, namely just south of the Arctic Circle, as Iceland. -

Historicising Ambergris in the Anthropocene

Historicising Ambergris in the Anthropocene Erin Hortle Figure 1: ‘Ambergris’. Photo: Erin Hortle, 2017. © Australian Humanities Review 63 (November 2018). ISSN: 1325 8338 Australian Humanities Review (November 2018) 49 HIS PIECE OF WRITING IS AN EXPERIMENTAL HISTORY OF A NUGGET OF AMBERGRIS that washed up on the south west coast of Tasmania. It’s also a confession. T When it’s fresh, ambergris smells like briny cow shit, or it smelt like that to me when I sniffed this piece, pictured here. This wasn’t what I expected, given the fact that ambergris is an integral ingredient of perfume. In the twenty-first century its value has dwindled slightly because many perfume makers are now brewing their wares from synthetic substances; however, it remains unsurpassed as a scent stabiliser and fixer and thus is still a much sought-after product that has, at times, been worth more than its weight in gold (Clarke 10). And there it was, sitting on the shoreline of a beach in the remote south west of Tasmania. The shoreline: remote, but not so remote in this globalised world. If you are human, you can only get there by boat or days on foot. But if you are buoyant ambergris, or if you are marine debris—perhaps carelessly tossed into the ocean, or perhaps inadequately fastened to a ship—you can ride the Roaring Forties across the Indian Ocean to arrive on Tasmania’s shores. I’ve struck gold, I thought to myself, when I spied the black little mass. But later I found out that I hadn’t. -

Lifting the International Whaling Commission's Moratorium on Commercial Whaling As the Most Effective Global Regulation of Whaling

LIFTING THE INTERNATIONAL WHALING COMMISSION'S MORATORIUM ON COMMERCIAL WHALING AS THE MOST EFFECTIVE GLOBAL REGULATION OF WHALING Lisa Kobayashi* TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRO DU CTION ................................................................................................. 179 1. THE HISTORY OF WHALING AND EARLY REGULATIONS ..................... 180 A. The History of Whaling............................. 180 B. Pre-IWC Attempts to Regulate Whaling ..................................... 184 1. Private Agreements Among Whaling Companies ............... 184 2. International Agreements before World War II ................... 186 3. The Establishment of the IW C ............................................ 188 II. LEGAL FRAMEWORK AND FUNCTION OF THE IWC ............................. 188 A. Purposeof the ICR W .................................................................. 189 B. Frameworkof the IW C ............................................................... 189 1. Schedules ............................................................................. 190 2. R ecom m endations .............................. ................................ 191 3. C om m ittees .......................................................................... 19 1 IIl. THE IWC SHIFTS FOCUS FROM PRESERVING THE WHALING INDUSTRY TOWARD PROTECTION OF WHALES - THE MOVEMENT TO STOP W HALIN G ............................................................................. 193 A. Adoption of the Moratorium ........................... 193 1. Introduction in 1972 ............................................................ -

Annual Assessment of Subsistence Bowhead Whaling Near Cross Island, 2001-2007 Final Report

cANIMIDA Task 7 /OCS Study MMS 2009-038 Annual Assessment of Subsistence Bowhead Whaling Near Cross Island, 2001-2007 Final Report Contract Numbers 1435-01-04-CT-32149 and M04PC00032 Prepared for: U.S. Department of the Interior Minerals Management Service Alaska Outer Continental Shelf Region Anchorage, AK Prepared by: Applied Sociocultural Research Anchorage, AK U.S. Department of the Interior Minerals Management Service Alaska Outer Continental Shelf Region cANIMIDA Task 7 Annual Assessment of Subsistence Bowhead Whaling Near Cross Island, 2001-2007 Final Report for: U.S. Department of the Interior Minerals Management Service Alaska Outer Continental Shelf Region Anchorage, AK by: Michael Galginaitis Applied Sociocultural Research 519 West Eighth Avenue, Suite 204 Post Office Box 99510 Anchorage, AK 99510-1352 This study was funded by the U.S. Department of the Interior, Minerals Management Service (MMS), Alaska Outer Continental Shelf Region, Anchorage, Alaska under Contracts No. 1435- 01-04-CT-32149 and M04PC00032, as part of the MMS Alaska Environmental Studies Program The opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Department of the Interior, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use by the Federal Government. July 2009 Back of Title Page Intentionally left blank (except for this notice) for purposes of pagination Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................................ -

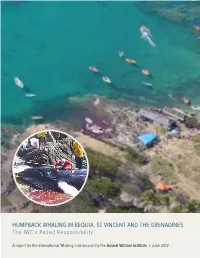

Report on Whaling in St. Vincent and the Grenadines

HUMPBACK WHALING IN BEQUIA, ST VINCENT AND THE GRENADINES The IWC’s Failed Responsibility A report for the International Whaling Commission by the Animal Welfare Institute | June 2012 HUMPbacK WHALING INTRODUCTION Since the Caribbean nation of St Vincent and the Grenadines (hereafter SVG) joined the International Whaling Commission (IWC or Commission) IN BEQUIA, in 1981, whalers on the Grenadine island of Bequia are reported to have struck and landed twenty-nine humpback whales (Megaptera ST VINCENT AND novaeangliae) and struck and lost at least five more. While this constitutes a small removal from a population of whales estimated to number over THE GRENADINES 11,0001, it does not excuse the IWC’s three decades of inattention to many problems with the hunt, including the illegal killing of at least nine The IWC’s Failed Responsibility humpback whale calves. Humpback whaling in SVG commenced in 1875 as a primarily commercial activity. In the 1970s, the focus of the operation changed from whale oil for export to meat and blubber for domestic consumption and a small scale artisinal hunt continued in Bequia despite the IWC’s ban on hunting North Atlantic humpback whales. In 1987, the IWC accepted SVG’s assurances that the Bequian whaling operation would not outlast its last surviving harpooner and granted SVG an Aboriginal Subsistence Whaling (ASW) quotai. Since then, the IWC has renewed SVG’s ‘temporary’ ASW quota six more times, including doubling it in 2002, two years after the harpooner died. With the exception of a handful of countries -

Two Competing Models of Activism, One Goal: a Case Study of Anti-Whaling Campaigns in the Southern Ocean

Comment Two Competing Models of Activism, One Goal: A Case Study of Anti-Whaling Campaigns in the Southern Ocean Anthony L.I. Moffat Let him, then, have powers commensurate with his utmost possible need; only let him be held strictly responsible for the exercise of them. Any other course would be injustice, as well as badpolicy. -Richard Henry Dana, Jr. I. INTRODUCTION In February 2011, in the midst of Japan's widely-criticized research whale hunt, the Japanese Agriculture Minister Michihiko Kano called the whaling fleet home months ahead of plan and hundreds short of its kill quota. The reason given for the abrupt end to the whaling season was harassment by a nongovernmental organization (NGO) called the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society (Sea Shepherds). 2 For years, the Japanese fleet had taken pride in its ability to outrun environmental activists,3 and Japan had refused to put an end to its research whaling operations in the face of resolutions from the International Whaling Commission (IWC)4 and repeated cessation requests. Ultimately, it was confrontation instigated by a renegade group, rather than any international resolution or NGO pressure, that brought an abrupt end to Japan's controversial whaling practices. In recent years, the NGO community has played an increasingly important and well-recognized role in shaping international law and in focusing enforcement resources. As a result, NGOs have earned invitations as official delegates to several major international conventions, particularly those t Yale Law School, J.D. expected 2012. Thanks to Professors W. Michael Reisman and ROdiger Wolfrum for providing initial guidance and the forum to develop the idea contained herein. -

The Spermaceti Candle and the American Whaling Industry

The Spermaceti Candle and the American Whaling Industry Emily Irwin ___________________________________________________________ Burning longer, cleaner, and brighter, the spermaceti candle was the height of candle-making technology for Americans in the 18th and 19th centuries. Important figures in American history, including Benjamin Franklin and George Washington, are believed to have favored the spermaceti candle for its superior burning ability.1 The spermaceti candle represents a changing society and an evolving culture; a culture that was constantly striving for a clean burning and more efficient means by which to light the darkness. The spermaceti candle holds even greater historical importance than simply a new artificial lighting source. Demand for spermaceti dramatically impacted the American East Coast whaling industry, as spermaceti can only be found in one species of whale: the sperm whale.2 The perils associated with retrieving spermaceti from sperm whales, as well as the lengthy production process, kept the cost of the spermaceti candle high and allowed only the richest of Americans to fully enjoy the benefits of this type of candle. However, despite high cost, demand remained high through much of the 18th and 19th centuries, fueling the whaling industry well into the early 20th century. To fully understand the significance of the spermaceti candle on early Americans, the complexities of the American whaling industry must also be explored. Early American lighting is the subject of many scholarly works. Arthur H. Hayward’s Colonial Lighting has long been a standard on the topic of artificial lighting. Other, more general works include Leroy Thwing’s Flickering Flames and F.W.