Parity in Practice Shared Equity Scenarios in Parkside and St

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

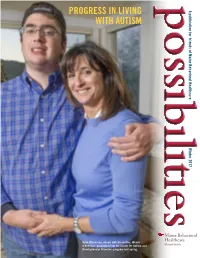

Progress in Living with Autism the O’Donovan Family Has Benefited from the Developmental Disorders Program

possibilities PROGRESS IN LIVING A publication for friends of Maine Behavioral Healthcare WITH AUTISM Winter 2017 Maine Behavioral Ryan O’Donovan, shown with his mother, Wendi Healthcare O’Donovan, graduated from the Center for Autism and MaineHealth 2 Developmental Disorders program last spring. A LETTER FROM STEPHEN MERZ IN THIS ISSUE Dear Friends: A LETTER FROM STEPHEN MERZ 2 Welcome to our new FAMILY HAS BENEFITED FROM THE DEVELOPMENTAL publication, Possibilities, DISORDERS PROGRAM 3 which is intended to provide you with useful information NEW INITIATIVE CONNECTS PATIENTS WITH CARE QUICKLY 5 about Maine Behavioral ROBYN OSTRANDER, MD, IS OPTIMISTIC ABOUT TREATING Healthcare (MBH) and CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS 6 showcase our progress in building a comprehensive system of behavioral LUNDER FAMILY ALLIANCE MAKES ALL THE DIFFERENCE 7 health services throughout Maine and eastern New Hampshire. A MESSAGE FROM THE DEVELOPMENT COMMITTEE CHAIR 8 • In this inaugural issue, you will read about Ryan THANK YOU TO OUR 2016 DONORS 8 O’Donovan, a young man with autism who benefited from our outstanding Developmental SIGNS OF HOPE EVENT BENEFITS LUNDER FAMILY ALLIANCE 11 Disorders Program and whose family members responded with a gift that is appreciated by the program’s patients. • Another article features Robyn Ostrander, MD, the new Chair of the Glickman Center for Child & Ado- Maine Behavioral Healthcare lescent Psychiatry, who oversees the most compre- MaineHealth hensive array of treatment, training and research programs in youth psychiatry north of Boston. To learn more about Maine Behavioral Healthcare or to schedule a visit to • You’ll read how the Lunder Family Alliance at see the difference you make through your support of our mission, please Spring Harbor Hospital helped a young woman contact us. -

Coffin, Frank Morey, Shep Lee, Edmund S. Muskie and Don Nicoll Oral History Interview Chris Beam

Bates College SCARAB Edmund S. Muskie Oral History Collection Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library 8-6-1991 Coffin, Frank Morey, Shep Lee, Edmund S. Muskie and Don Nicoll oral history interview Chris Beam Follow this and additional works at: http://scarab.bates.edu/muskie_oh Recommended Citation Beam, Chris, "Coffin,r F ank Morey, Shep Lee, Edmund S. Muskie and Don Nicoll oral history interview" (1991). Edmund S. Muskie Oral History Collection. 92. http://scarab.bates.edu/muskie_oh/92 This Oral History is brought to you for free and open access by the Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library at SCARAB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Edmund S. Muskie Oral History Collection by an authorized administrator of SCARAB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Interview with Edmund S. Muskie, Shep Lee, Don Nicoll and Frank Coffin by Chris Beam Summary Sheet and Transcript Interviewee Coffin, Frank Morey Lee, Shep Muskie, Edmund S., 1914-1996 Nicoll, Don Interviewer Beam, Chris Date August 6, 1991 Place Kennebunk, Maine ID Number MOH 022 Use Restrictions © Bates College. This transcript is provided for individual Research Purposes Only ; for all other uses, including publication, reproduction and quotation beyond fair use, permission must be obtained in writing from: The Edmund S. Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library, Bates College, 70 Campus Avenue, Lewiston, Maine 04240-6018. Biographical Note Frank Coffin Frank Morey Coffin was born in Lewiston, Maine on July 11, 1919. His parents were Ruth [Morey] and Herbert Coffin, who divorced when Frank was twelve. Ruth raised Frank alone on Wood St. -

Learning and Innovation Go Hand in Hand. the Arrogance of Success Is to Believe That What You Did Yesterday Will Be Sufficient for Tomorrow.”

Questions, Comments, Story Ideas? Send them to [email protected] July 12, 2017 “Learning and innovation go hand in hand. The arrogance of success is to believe that what you did yesterday will be sufficient for tomorrow.” - William Pollard The Scope appreciates the enthusiastic response of readers contributing quotes. Please submit a favorite you’d like to share with others by emailing The Scope. A Compact Between Maine Medical Center and Its Medical Staff Peer Support for the MMC Medical Staff [email protected] Physician leader: Christine Irish, MD Confidential * One-on-One * Peer Support Dear Members of the Maine Medical Center Medical Staff, Happy July! This month we welcome our new interns and celebrate the value of Innovation. Below, you’ll find an issue packed with informative articles ranging from MaineHealth’s position on national healthcare legislation to updates on opioid prescribing and information from Dr. Jennifer Hayman about medication practice alerts. The iPACE unit opened at MMC on P2C at the end of June. Teams of health professionals and trainees are working in new ways to achieve one plan of care, one progress note and deliver one message to the patient. We give a special shout out to Christyna McCormack and Dr. Tom Van der Kloot for their creative and effective CLER (Clinical Learning Environment Review) focus area CLIPS. Please review, copy, share, post and promote these potent tools which convey information on key elements about our academic medical center. Please welcome the Joint Commission surveyors this week. Now is a good time to check your safety knowledge with the Top Ten Joint Commission Fill-in-the-Blank Challenge. -

Maine Medical Center Research Institute: 2017 Year in Review

MaineHealth MaineHealth Knowledge Connection Annual Reports Institutional History and Archives 2017 Maine Medical Center Research Institute: 2017 Year in Review Maine Medical Center Research Institute Follow this and additional works at: https://knowledgeconnection.mainehealth.org/annualreports Part of the Medical Education Commons, and the Translational Medical Research Commons Recommended Citation Maine Medical Center Research Institute, "Maine Medical Center Research Institute: 2017 Year in Review" (2017). Annual Reports. 1. https://knowledgeconnection.mainehealth.org/annualreports/1 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Institutional History and Archives at MaineHealth Knowledge Connection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Annual Reports by an authorized administrator of MaineHealth Knowledge Connection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maine Medical Center Research Institute 2017 Year in Review www.mmcri.org Bench to Bedside to Community Basic Research Translational & Clinical Research Patient-Centered Outcomes Research TABLE OF CONTENTS Leadership & 2017 Stats 4 Biomedical Research 5 Clinical & Translational Research 8 Psychiatric Research 10 Health Outcomes Research 12 Education 14 2 Dr. Don St. Germain MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR Dear Friends, Each year as the foliage is starting to garner our attention and as our fiscal year is coming to a close, I give a State of the Institute presentation to our faculty and staff. The presentation focuses on institutional and individual successes, opportunities going forward, and challenges old and new. Not surprisingly, part of the presentation is a report on the grant funding the Institute has received during the prior 12 months. It is the nature of our business that extramural funding ebbs and flows from month to month and year to year as new grants are awarded and older ones expire. -

Forest Avenue and Stevens Avenue Portland, Maine Historic Context

Forest Avenue and Stevens Avenue Portland, Maine Historic Context Scott T. Hanson Sutherland Conservation & Consulting August 2015 General context Development of Colonial Falmouth European settlement of the area that became the city of Portland, Maine, began with English settlers establishing homes on the islands of Casco Bay and on the peninsula known as Casco Neck in the early seventeenth century. As in much of Maine, early settlers were attracted by abundant natural resources, specifically fish and trees. Also like other early settlement efforts, those at Casco Bay and Casco Neck were tenuous and fitful, as British and French conflicts in Europe extended across the Atlantic to New England and both the French and their Native American allies frequently sought to limit British territorial claims in the lands between Massachusetts and Canada. Permanent settlement did not come to the area until the early eighteenth century and complete security against attacks from French and Native forces did not come until the fall of Quebec to the British in 1759. Until this historic event opened the interior to settlement in a significant way, the town on Casco Neck, named Falmouth, was primarily focused on the sea with minimal contact with the interior. Falmouth developed as a compact village in the vicinity of present day India Street. As it expanded, it grew primar- ily to the west along what would become Fore, Middle, and Congress streets. A second village developed at Stroudwater, several miles up the Fore River. Roads to the interior were limited and used primarily to move logs to the coast for sawing or use as ship’s masts. -

TUSM MMC Maine Track

2019 PROGRAM REPORT . TUSM MMC Maine Track Undergraduate Medical Education Teaching Partnership TUSM MMC Maine Track – Founded with three primary goals in mind: to address the shortage of doctors in Maine; to offer Maine’s brightest students the financial means to pursue a career in medicine; and to develop an innovative curriculum focused on community-based education. CLASS OF 2019 • More than half of this year’s class will remain Congratulations, in New England for their residency, primarily Maine Track Class of 2019! in Maine, Massachusetts, Vermont, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island. Six graduates of With the addition of this class, the Class of 2019 matched to Maine Medical there are now more than Center! 240 graduates of the Maine Track—a significant contribution • Four of this year’s class have matched to to addressing the physician residencies with an explicit focus on rural medicine, including our own Rural Internal workforce shortage in Maine. Medicine Maine residency program at Stephens Nearly half of all Maine Track Memorial in Norway, Maine. There are relatively graduates have matched to few of these programs, and often there is only primary care residencies, far one spot available each year, which speaks to the exceeding the nationwide high qualifications of our Maine Track graduates. rate of 35%. Welcome, Maine Track Class of 2023! This class is the first to matriculate under the new 10-year agreement between Maine Medical Center and Tufts University School of Medicine. As part of the new agreement, students will spend their entire second year in Maine, instead of splitting their time between Maine and Boston. -

Congratulations to the 2020 Gold Star Standards of Excellence Awardees

Congratulations to the 2020 Gold Star Standards of Excellence Awardees Hospital Awardees PLATINUM Cary Medical Center PLATINUM New England Rehabilitation Hospital PLATINUM Franklin Memorial Hospital PLATINUM Northern Light Eastern Maine Medical Center PLATINUM Houlton Regional Hospital PLATINUM Northern Maine Medical Center PLATINUM LincolnHealth PLATINUM Pen Bay Medical Center PLATINUM Maine Medical Center PLATINUM Redington-Fairview General Hospital PLATINUM MaineGeneral Medical Center PLATINUM Southern Maine Health Care PLATINUM Mid Coast Hospital PLATINUM Spring Harbor Hospital PLATINUM Millinocket Regional Hospital PLATINUM St. Mary's Regional Medical Center PLATINUM Mount Desert Island Hospital PLATINUM Waldo County General Hospital GOLD Bridgton Hospital GOLD Northern Light Charles A. Dean Memorial Hospital GOLD Calais Regional Hospital GOLD Northern Light Maine Coast Memorial Hospital GOLD Central Maine Medical Center GOLD Northern Light Mercy Hospital GOLD Down East Community Hospital GOLD Rumford Hospital GOLD Northern Light AR Gould Hospital GOLD St. Joseph's Hospital GOLD Northern Light Blue Hill Memorial Hospital GOLD Stephens Memorial Hospital SILVER Northern Light Inland Hospital SILVER VA Maine Healthcare System SILVER Northern Light Sebasticook Valley Hospital Individual Gold Star Awardees Bob Peterson - Millinocket Regional Hospital Casey J. Ellis- Waldo County General Hospital Jane Danforth - Millinocket Regional Hospital Leannne Temple - Waldo County General Hospital Healthcare Awardees PLATINUM Cape Integrative Health GOLD Hometown Health Center SILVER India Street Clinic PLATINUM Casco Bay Dental GOLD Oasis Free Clinics Individual Gold Star Awardees Robin Winslow - Hometown Health Center - Newport. -

NERIC Program

AGENDA Wednesday, August 14, 2019 2:00 – 9:30 pm Registration Desk Hours of Operation Webster Franklin Foyer PEARL Meeting Washington Program Evaluation and Administration of Research Board Room Leaders – by invitation 5:00 – 6:00 pm Reception The Conservatory & Veranda 5:00 – 6:00 pm Poster Session I Set up Adams & Madison Rooms 6:00 – 6:15 pm Welcoming Remarks Dining Room William Green, Ph.D. Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, PI, NH INBRE Dean Madden, Ph.D. Dartmouth College, Vice Provost for Research 6:15 – 7:30 pm Buffet Dinner Dining Room 7:30 – 9:00 pm Dessert and Poster Session I Adams & (Student and Core Posters) Madison Rooms 1 AGENDA Thursday, August 15, 2019 7:00 – 5:30 pm Registration Desk Hours of Operation Webster Franklin Foyer 7:00 – 8:00 am One-on-One Mentoring Dining Room Drop-in or Upon Request 7:30 – 8:30 am Breakfast Topic Tables Dining Room Possible topics include: Career Choices Undergrad engagement Graduate and Medical Schools IDeA Entrepreneurship SURF management 8:45 – 9:15 am Opening Remarks and Introduction: Grand Ballroom William Green, Ph.D. Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, PI, NH INBRE Ming Lei, Ph.D. Director of the Division for Research Capacity Building 9:15 – 9:40 am Ravi Basavappa, Ph.D. Grand Ballroom Program Leader, Office of Strategic Coordination “The High-Risk High-Reward Research Program in the NIH Common Fund: Funding opportunities for exceptionally creative scientists at all career stages.” 9:40 – 9:50 am Krishan K. Arora, Ph.D. Grand Ballroom IDeA Program Director 9:50 – 10:10 am Jake Reder, Ph.D. -

The Maine Medical Center Tufts University School of Medicine

The Maine Medical Center Tufts University School of Medicine Maine Track Program The Maine Medical Center Tufts University School of Medicine Maine Track Program was founded with three primary goals in mind: to address the shortage of doctors in Maine, especially in our rural areas; to offer Maine’s brightest students the financial means to pursue a career in medicine; and to develop an innovative curriculum focused on community-based education. This unique partnership offers a rigorous training program focused on the needs of Maine while also giving students firsthand experience providing care in local communities throughout the state. This approach creates more than just a pipeline of new physicians; it lays the foundation for a future where every Mainer has access to excellent medical care. “ My dream is to provide care to Maine’s island communities as a traveling doctor.” Marya Spurling | Class of 2013 Growing up as the daughter of a lobsterman on an island of only 75 residents, Marya knows firsthand the challenges HOMETOWN: of living in a remote location and the deep sense of Little Cranberry Island community that comes from that experience. She chose SCHOLARSHIP: the Maine Track Program because of the unique structure Doctors for Maine’s of a curriculum focused on rural medicine and the Future Program opportunity to complete clinical rotations here in Maine. UNDERGRADUATE: This one-of-a-kind education will provide her with impor- Gordon College tant connections as she looks to build her own practice. “ Maine reminds me of the courage my parents displayed when they decided on a different future. -

Excellence Simulation Annual Report 2020 the Mainehealth System in This Annual Report

10 YEARS OF EXCELLENCE SIMULATION ANNUAL REPORT 2020 THE MAINEHEALTH SYSTEM IN THIS ANNUAL REPORT Â MEDICAL DIRECTOR LETTER ....................................................................................6 REGIONAL MEDICAL DIRECTOR LETTER ............................................................7 Â REGIONAL ENTITIES MAINEHEALTH ACCOUNTABLE CARE ORGANIZATION IN MEMORY OF JOHN R. DARBY, MD ...............................................................8-9 Â MAINE BEHAVIORAL HEALTHCARE MAINEHEALTH CARE AT HOME IN THE PRESS ........................................................................................................... 10-17 Â NORDX Â CELEBRATING 10 YEARS OF EXCELLENCE ................................................. 18-19 MEET THE TEAM ......................................................................................................20-21 Â FRANKLIN COMMUNITY HEALTH NETWORK BEHIND THE SCENES .......................................................................................... 22-25 Â COASTAL HEALTHCARE ALLIANCE WALDO COUNTY GENERAL HOSPITAL PEN BAY MEDICAL CENTER BY THE NUMBERS ................................................................................................. 26-27 Â LINCOLNHEALTH MILES CAMPUS ST. ANDREWS CAMPUS PATIENTS ...................................................................................................................28-35 WESTERN MAINE HEALTH Â MID COAST-PARKVIEW HEALTH SPRING HARBOR HOSPITAL PEOPLE ..................................................................................................................... -

Mainehealth 2020

STRATEGIC PLAN 2020-2022 REVISED SEPTEMBER 2020 - MISSION MaineHealth is a not-for-profit health system dedicated to improving the health of our patients and communities by providing high-quality affordable care, educating tomorrow's caregivers, and researching better ways to provide care. VISION Working together so our communities are the healthiest in America This document sets forth, at a high level, MaineHealth’s course over the next three years and articulates a shared mission and vision, as the system and its local health systems work together toward common goals. It explains our organization’s strategic priorities and offers direction for on-going planning, helping to guide critical decisions STRATEGIC PRIORITIES regarding resource allocation, including both capital and human resources, as well as how we navigate the opportunities and challenges ahead. This Strategic Plan outlines a clear path for advancing our vision for the future, and provides the framework for establishing our detailed set of annual objectives. VALUES CULTURE STRATEGIC PRIORITIES At MaineHealth, our culture drives our strategy. These four strategic priorities form the foundation for our efforts over the next three years and determine the system’s strategic direction. In essence, these priorities are our We use distinct words or phrases to describe our culture. Some are contained within our interpretation of the Quadruple Aim: 1) Enhance the Patient Experience (including values: Patient Centered, Respect, Integrity, Excellence, Ownership and Innovation, and quality, safety and service), 2) Improve Care Team Well-Being, 3) Improve Population the implicit behaviors associated with each. Others include collaboration and cooperation; Health, and 4) Make Care More Affordable. -

MMC Nursing...Caring Through Leadership, Knowledge & Compassion

MaineHealth MaineHealth Knowledge Connection Annual Reports Institutional History and Archives 2008 MMC Nursing...Caring Through Leadership, Knowledge & Compassion Maine Medical Center Follow this and additional works at: https://knowledgeconnection.mainehealth.org/annualreports Part of the Nursing Administration Commons Recommended Citation Maine Medical Center, "MMC Nursing...Caring Through Leadership, Knowledge & Compassion" (2008). Annual Reports. 7. https://knowledgeconnection.mainehealth.org/annualreports/7 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Institutional History and Archives at MaineHealth Knowledge Connection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Annual Reports by an authorized administrator of MaineHealth Knowledge Connection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REPORT ON NURSING 2007-2008 / VOLUME 1 MMC Nursing...Caring through Leadership, Knowledge & Compassion Message I am delighted to present this two-volume Report on Nursing for 2007-2008. The report is filled with the many accomplish- ments of our extraordinary nursing staff and leadership across the hospital. Volume 1 begins with our Nursing Vision, Mis- sion & Philosophy created by our nurses in 2002. Those foun- dational statements come to life with the many achievements that fill this report. The pursuit of excellence in patient care is exemplified in the many quality initiatives listed in both volumes. The Partnership Care Delivery Model found in the Innovations in Practice section demonstrates Maine Medical Center’s commitment to empowering patients and engaging them in their care as full partners. Volume 2 identifies evidence based practice changes that have evolved to sup- port the concept of partnership with the patient and family. I am pleased to report that new projects are continuously emerging.