Print This Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heraldry Arms Granted to Members of the Macneil, Mcneill, Macneal, Macneile Families

Heraldry Arms granted to members of the MacNeil, McNeill, Macneal, MacNeile families The law of heraldry arms In Scotland all things armorial are governed by the laws of arms administered by the Court of the Lord Lyon. The origin of the office of Lord Lyon is shrouded in the mists of history, but various Acts of Parliament, especially those of 1592 and 1672 supplement the established authority of Lord Lyon and his brother heralds. The Lord Lyon is a great officer of state and has a dual capacity, both ministerial and judicial. In his ministerial capacity, he acts as heraldic advisor to the Sovereign, appoints messengers-at-arms, conducts national ceremony and grants arms. In his judicial role, he decides on questions of succession, authorizes the matriculation of arms, registers pedigrees, which are often used as evidence in the matter of succession to peerages, and of course judges in cases when the Procurator Fiscal prosecutes someone for the wrongful use of arms. A System of Heraldry Alexander Nisbet Published 1722 A classic standard heraldic treatise on heraldry, organized by armorial features used, and apparently attempting to list arms for every Scottish family, alive at the time or extinct. Nesbit quotes the source for most of the arms included in the treatis alongside the blazon A System of Heraldry is one of the most useful research sources for finding the armory of a Scots family. It is also the best readily available source discussing charges used in Scots heraldry . The Court of the Lord Lyon is the heraldic authority for Scotland and deals with all matters relating to Scottish Heraldry and Coats of Arms and maintains the Scottish Public Registers of Arms and Genealogies. -

Camelot the Articles in This Study Guide Are Not Meant to Mirror Or Interpret Any Productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival

Insights A Study Guide to the Utah Shakespeare Festival Camelot The articles in this study guide are not meant to mirror or interpret any productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival. They are meant, instead, to be an educational jumping-off point to understanding and enjoying the plays (in any production at any theatre) a bit more thoroughly. Therefore the stories of the plays and the interpretative articles (and even characters, at times) may differ dramatically from what is ultimately produced on the Festival’s stages. The Study Guide is published by the Utah Shakespeare Festival, 351 West Center Street; Cedar City, UT 84720. Bruce C. Lee, communications director and editor; Phil Hermansen, art director. Copyright © 2011, Utah Shakespeare Festival. Please feel free to download and print The Study Guide, as long as you do not remove any identifying mark of the Utah Shakespeare Festival. For more information about Festival education programs: Utah Shakespeare Festival 351 West Center Street Cedar City, Utah 84720 435-586-7880 www.bard.org. Cover photo: Anne Newhall (left) as Billie Dawn and Craig Spidle as Harry Brock in Born Yesterday, 2003. Contents InformationCamelot on the Play Synopsis 4 Characters 5 About the Playwright 6 Scholarly Articles on the Play A Pygmalion Tale, but So Much More 8 Well in Advance of Its Time 10 Utah Shakespeare Festival 3 8FTU$FOUFS4USFFUr $FEBS$JUZ 6UBIr Synopsis: Camelot On a frosty morning centuries ago in the magical kingdom of Camelot, King Arthur prepares to greet his promised bride, Guenevere. Merlyn the magician, the king’s lifelong mentor, finds Arthur, a reluctant king and even a more reluctant suitor, hiding in a tree. -

The Scottish Background of the Sydney Publishing and Bookselling

NOT MUCH ORIGINALITY ABOUT US: SCOTTISH INFLUENCES ON THE ANGUS & ROBERTSON BACKLIST Caroline Viera Jones he Scottish background of the Sydney publishing and bookselling firm of TAngus & Robertson influenced the choice of books sold in their bookshops, the kind of manuscripts commissioned and the way in which these texts were edited. David Angus and George Robertson brought fi'om Scotland an emphasis on recognising and fostering a quality homegrown product whilst keeping abreast of the London tradition. This prompted them to publish Australian authors as well as to appreciate a British literary canon and to supply titles from it. Indeed, whilst embracing his new homeland, George Robertson's backlist of sentimental nationalistic texts was partly grounded in the novels and verse written and compiled by Sir Walter Scott, Robert Bums and the border balladists. Although their backlist was eclectic, the strong Scottish tradition of publishing literary journals, encyclopaedias and religious titles led Angus & Robertson, 'as a Scotch firm' to produce numerous titles for the Presbyterian Church, two volumes of the Australian Encyclopaedia and to commission writers from journals such as the Bulletin. 1 As agent to the public and university libraries, bookseller, publisher and Book Club owner, the firm was influential in selecting primary sources for the colony of New South Wales, supplying reading material for its Public Library and fulfilling the public's educational and literary needs. 2 The books which the firm published for the See Rebecca Wiley, 'Reminiscences of George Robertson and Angus & Robertson Ltd., 1894-1938' ( 1945), unpublished manuscript, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, ML MSS 5238. -

My Fair Lady

The Lincoln Center Theater Production of TEACHER RESOURCE GUIDE Teacher Resource Guide by Sara Cooper TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION . 1 THE MUSICAL . 2 The Characters . 2 The Story . 2 The Writers, Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe . 5 The Adaptation of Pygmalion . 6 Classroom Activities . 7 THE BACKDROP . 9 Historical Context . 9 Glossary of Terms . 9 Language and Dialects in Musical Theater . 10 Classroom Activities…………… . 10 THE FORM . 13 Glossary of Musical Theater Terms . 13 Types of Songs in My Fair Lady . 14 The Structure of a Standard Verse-Chorus Song . 15 Classroom Activities . 17 EXPLORING THE THEMES . 18 BEHIND THE SCENES . 20 Interview with Jordan Donica . 20 Classroom Activities . 21 Resources . 22 INTRODUCTION Welcome to the teacher resource guide for My Fair Lady, a musical play in two acts with book and lyrics by Alan Jay Lerner and music by Frederick Loewe, directed by Bartlett Sher. My Fair Lady is a musical adaptation of George Bernard Shaw’s play Pygmalion, itself an adaptation of an ancient Greek myth. My Fair Lady is the story of Eliza Doolittle, a penniless flower girl living in London in 1912. Eliza becomes the unwitting object of a bet between two upper-class men, phonetics professor Henry Higgins and linguist Colonel Pickering. Higgins bets that he can pass Eliza off as a lady at an upcoming high-society social event, but their relationship quickly becomes more complicated. In My Fair Lady, Lerner and Loewe explore topics of class discrimination, sexism, linguistic profiling, and social identity; issues that are still very much present in our world today. -

Campbell." Evidently His Was a Case of an Efficient, Kindly Officer Whose Lot Was Cast in Uneventful Lines

RECORDS of CLAN CAMPBELL IN THE MILITARY SERVICE OF THE HONOURABLE EAST INDIA COMPANY 1600 - 1858 COMPILED BY MAJOR SIR DUNCAN CAMPBELL OF BARCALDINE, BT. C. V.o., F.S.A. SCOT., F.R.G.S. WITH A FOREWORD AND INDEX BY LT.-COL. SIR RICHARD C. TEMPLE, BT. ~ C.B., C.I.E., F.S.A., V.P.R,A.S. LONGMANS, GREEN AND CO. 39 PATERNOSTER ROW, LONDON, E.C. 4 NEW YORK, TORONTO> BOMBAY, CALCUTTA AND MADRAS r925 Made in Great Britain. All rights reserved. 'Dedicated by Permission TO HER- ROYAL HIGHNESS THE PRINCESS LOUISE DUCHESS OF ARGYLL G.B.E., C.I., R.R.C. COLONEL IN CHIEF THE PRINCESS LOUISE'S ARGYLL & SUTHERLAND HIGHLANDERS THE CAMPBELLS ARE COMING The Campbells are cowing, o-ho, o-ho ! The Campbells are coming, o-ho ! The Campbells are coming to bonnie Loch leven ! The Campbells are coming, o-ho, o-ho ! Upon the Lomonds I lay, I lay ; Upon the Lomonds I lay; I lookit down to bonnie Lochleven, And saw three perches play. Great Argyle he goes before ; He makes the cannons and guns to roar ; With sound o' trumpet, pipe and drum ; The Campbells are coming, o-ho, o-ho ! The Camp bells they are a' in arms, Their loyal faith and truth to show, With banners rattling in the wind; The Campbells are coming, o-ho, o-ho ! PREFACE IN the accompanying volume I have aimed at com piling, as far as possible, complete records of Campbell Officers serving under the H.E.I.C. -

The Clan Macneil

THE CLAN MACNEIL CLANN NIALL OF SCOTLAND By THE MACNEIL OF BARRA Chief of the Clan Fellow of the Society of .Antiquarie1 of Scotland With an Introduction by THE DUKE OF ARGYLL Chief of Clan Campbell New York THE CALEDONIAN PUBLISHING COMPANY MCMXXIII Copyright, 1923, by THE CALEDONIAN PUBLISHING COMPANY Entered at Stationers~ Hall, London, England .All rights reser:ved Printed by The Chauncey Holt Compan}'. New York, U. 5. A. From Painting by Dr. E, F. Coriu, Paris K.1s11\1 UL CASTLE} IsLE OF BAH HA PREFACE AVING a Highlander's pride of race, it was perhaps natural that I should have been deeply H interested, as a lad, in the stirring tales and quaint legends of our ancient Clan. With maturity came the desire for dependable records of its history, and I was disappointed at finding only incomplete accounts, here and there in published works, which were at the same time often contradictory. My succession to the Chiefship, besides bringing greetings from clansmen in many lands, also brought forth their expressions of the opinion that a complete history would be most desirable, coupled with the sug gestion that, as I had considerable data on hand, I com pile it. I felt some diffidence in undertaking to write about my own family, but, believing that under these conditions it would serve a worthy purpose, I commenced this work which was interrupted by the chaos of the Great War and by my own military service. In all cases where the original sources of information exist I have consulted them, so that I believe the book is quite accurate. -

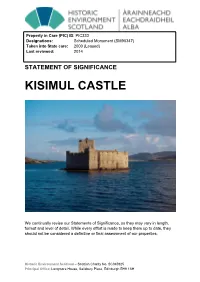

Kisimul Castle Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC333 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90347) Taken into State care: 2000 (Leased) Last reviewed: 2014 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE KISIMUL CASTLE We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2020 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH KISIMUL CASTLE SYNOPSIS Kisimul Castle (Caisteal Chiosmuil) stands on a small island in Castle Bay, at the south end of the island of Barra and a short distance off-shore of the town of Castlebay. -

Clan Macneil Association of America

Clan MacNeil Association of Australia Newsletter for clan members and friends. December 2010 Editor - John McNeil 21 Laurel Avenue, Linden Park, SA 5065 telephone 08 83383858 Items is this newsletter – more information for her from Calum MacNeil, • Welcome to new members genealogist on Barra. • Births, marriages and deaths • National clan gathering in Canberra Births, Marriages and Deaths • World clan gathering on Barra Aug. On 2 nd October John McNeil married Lisa van 2010 Grinsven at the Bird in hand winery in the • News from Barra Adelaide hills • Lunch with Cliff McNeil & Bob Neil • Jean Buchanan & John Whiddon at Daylesford highland gathering • Reintroduction of beavers to Knapdale • Proposal for a clan young adult program • Recent events • Coming events • Additions to our clan library • An update of the research project of the McNeill / MacNeil families living in Argyll 1400 -1800 AD • Clan MacNeil merchandise available to you • Berneray one of the Bishop’s isles south John is the son of Peter and Mary and grandson of Barra of Ronald McNeil, my cousin. He represents the fifth generation of a John McNeil in our family. Please join with me in congratulating them on New Members their marriage. I would like to welcome our new clan members who have joined since the last newsletter. We offer our deepest sympathy to Cliff McNeil Mary Surman on the death of his mother, Helen Mary McNeil Carol & John Searcy who died on 8 th November 2010, age 96 years. Phillip Draper Helen was a member of the committee for the Clan MacNeil Association of Australia in its Over recent months I have met with John early days in Sydney. -

A Adhamhar Foltchaion, 6. Aedhan Glas, Son of N Uadhas, 4. Aefa

INDEX A Aula£ the White, King of the Danes, 22. Adhamhar Foltchaion, 6. Auldearn, Battle of, 123. Aedhan Glas, son of N uadhas, 4. Aefa, daughter of Alpin, 9. B Agnomain, 1. Agnon, Fionn, 1. Bachca (Lorne), battle at, 58. Aileach, Fortress of, 14, 15. Badhbhchadh, 5. Ailill, son of Eochaidh, 12. Baile Thangusdail (Barra), 179. Aitlin, 4. Baine, daughter of Seal Balbh, 8. Airer Gaedhil (see ARGYLL). Baliol, Edward, 40. - Aithiochta, wife of Feargal IX, 19. Bannockburn, Battle of, 40. Alba (Scotland), 13. Baoth, 1. Alexander II, King of Scotland, 38. Bar, Barony of, Kintyre, 40. Alexander III, King of Scotland, 38. Barra, origin of name, 26, 150 et Alladh, 1. seq.; Allan, son of Ruari, 39. description, 167, 174, 179 et seq.; Allan nan Sop, (see ALLAN MAC- settled by the Macneils, 24; LEAN OF GrGHA). Charters, 42, 45, 83, 99; A11en, Battle of, 19. Norse occupation, 27-32 (see Alpin, King of the Picts, 9. Norsemen) ; America, Emigration to, 90, 93, 122, under Lordship of the Isles, 39, 133 et seq., 206, 207, 210. 41; Ancrum Moor, Battle of, 100. sale of, 137; Angus Og, son of John of the Isles, brooches, 28-31; 45. religion, 145 et seq. (see MAc A11n Ja11e, wreck of the, 195. NEIL). Antigonish, settlement at, 136. "Barra Song," 25. Aodh Aonrachan, 41. "Barra Register," quoted, 25, 33. Aodh, son of Aodh Aonrachan XX, Barton, Robert, 49. 24. Baruma, The (a tax), 19. Aoife, wife of Fiacha, 10. Battle customs, 161-164. Aongus Olmucach, 4. Bealgadain, Battle of, 4. Aongus Tuirneach-Teamrach, son of Bearnera, Isle, (see Berne ray). -

My Fair Lady

TEACHER RESOURCE GUIDE Teacher Resource Guide by Sara Cooper LINCOLN CENTER THEATER AT THE VIVIAN BEAUMONT André Bishop Adam Siegel Producing Artistic Director Hattie K. Jutagir Managing Director Executive Director of Development & Planning in association with Nederlander Presentations, Inc. presents LERNER & LOEWE’S Book and Lyrics Music Alan Jay Lerner Frederick Loewe Adapted from George Bernard Shaw’s play and Gabriel Pascal’s motion picture “Pygmalion” with Lauren Ambrose Harry Hadden-Paton Norbert Leo Butz Diana Rigg Allan Corduner Jordan Donica Linda Mugleston Manu Narayan Cameron Adams Shereen Ahmed Kerstin Anderson Heather Botts John Treacy Egan Rebecca Eichenberger SuEllen Estey Christopher Faison Steven Trumon Gray Adam Grupper Michael Halling Joe Hart Sasha Hutchings Kate Marilley Liz McCartney Justin Lee Miller Rommel Pierre O’Choa Keven Quillon JoAnna Rhinehart Tony Roach Lance Roberts Blair Ross Christine Cornish Smith Paul Slade Smith Samantha Sturm Matt Wall Michael Williams Minami Yusui Lee Zarrett Sets Costumes Lighting Sound Michael Yeargan Catherine Zuber Donald Holder Marc Salzberg Musical Arrangements Dance Arrangements Robert Russell Bennett & Phil Lang Trude Rittmann Mindich Chair Casting Hair & Wigs Production Stage Manager Musical Theater Associate Producer Telsey + Company Tom Watson Jennifer Rae Moore Ira Weitzman General Manager Production Manager Director of Marketing General Press Agent Jessica Niebanck Paul Smithyman Linda Mason Ross Philip Rinaldi Music Direction Ted Sperling Choreography Christopher Gattelli Directed by Bartlett Sher The Jerome L. Greene Foundation is the Lead Sponsor of MY FAIR LADY. Major support is also generously provided by: The Blanche and Irving Laurie Foundation • Florence Kaufman The New York Community Trust - Mary P. Oenslager Foundation Fund • The Ted & Mary Jo Shen Charitable Gift Fund The Bernard Gersten LCT Productions Fund • The Peter Jay Sharp Foundation’s Special Fund for LCT with additional support from the National Endowment for the Arts. -

Clan Macneil Association of New Zealand

Clan MacNeil Association of New Zealand September 2009 Newsletter: Failte – Welcome Welcome to the September edition, of the Clan MacNeil newsletter. Thanks to all those who have helped contribute content— keep it up. Tartan Day Celebrations Waikato - Bay of Plenty Clan Associations cele- brated Tartan Day on The 4th July at Tauranga. The day hosted by Clan Cameron was atttended by about 100 members from Waikato, the Bay of Plenty coming from as far away as Taumaranui. Clan MacNeil attendees were Pat Duncan, Judith Bean and new member Heather Peart. ―The rain held off for a very short march from a College field across the road into the Wesley Church Hall where the function was held. After the piping in of the Banners each Clan representative was invited to speak on behalf of their Clan which I duly did passing on greetings from Clan McNeil” said MacNeil participant Pat Duncan.‖ ―Ted Little our usual representative to this function was unable to attend and sent his apologies. Clan Cameron Chief gave a short speech outlining the outlawing of The Tartan and its reinstatement” added Duncan. Clans represented were; Clan Cameron, David- son, McArthur, Wallace, Gordon, Johnston (accompanied by their little granddaughters). McLoughlan, Donnachaidh and Stewart. Jessica McLachland danced having just returned The coffee cart did a great trade in the break be- from attending Homecoming Scotland with her fore the Haggis was piped in.The Address given grandfather, Dave, who also sang a selection of and attendees all participated in a wee dram (or songs with 3 others. Attendees were all invited to juice ) to toast the Haggis. -

![Frederick Loewe Collection [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5579/frederick-loewe-collection-finding-aid-library-of-congress-pdf-1055579.webp)

Frederick Loewe Collection [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF

Frederick Loewe Collection Guides to Special Collections in the Music Division of the Library of Congress Music Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2004 Revised 2017 June Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.music/perform.contact Additional search options available at: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.music/eadmus.mu012019 LC Online Catalog record: http://lccn.loc.gov/2012563808 Processed by the Music Division of the Library of Congress Collection Summary Title: Frederick Loewe Collection Span Dates: 1923-1988 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1945-1975) Call No.: ML31.L58 Creator: Frederick Loewe, 1901-1988 Extent: 1,000 items ; 13 containers ; 5 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Location: Music Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: Frederick Loewe was a German-born composer who wrote, with lyricist Alan Jay Lerner, the scores for such musicals as My Fair Lady, Camelot, Gigi, and Brigadoon. The collection contains music manuscripts from Loewe's stage and screen musicals, as well as individual songs not associated with a particular show. In addition, the collection contains photographs, a small amount of correspondence, clippings, business papers, writings, and programs. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Lerner, Alan Jay, 1918-1986. Lerner, Alan Jay, 1918-1986. Loewe, Frederick, 1901-1988--Correspondence. Loewe, Frederick, 1901-1988--Manuscripts. Loewe, Frederick, 1901-1988--Photographs. Loewe, Frederick, 1901-1988. Loewe, Frederick, 1901-1988.