Handel's Messiah

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Commissioned Orchestral Version of Jonathan Dove’S Mansfield Park, Commemorating the 200Th Anniversary of the Death of Jane Austen

The Grange Festival announces the world premiere of a specially- commissioned orchestral version of Jonathan Dove’s Mansfield Park, commemorating the 200th anniversary of the death of Jane Austen Saturday 16 and Sunday 17 September 2017 The Grange Festival’s Artistic Director Michael Chance is delighted to announce the world premiere staging of a new orchestral version of Mansfield Park, the critically-acclaimed chamber opera by composer Jonathan Dove and librettist Alasdair Middleton, in September 2017. This production of Mansfield Park puts down a firm marker for The Grange Festival’s desire to extend its work outside the festival season. The Grange Festival’s inaugural summer season, 7 June-9 July 2017, includes brand new productions of Monteverdi’s Il ritorno d'Ulisse in patria, Bizet’s Carmen, Britten’s Albert Herring, as well as a performance of Verdi’s Requiem and an evening devoted to the music of Rodgers & Hammerstein and Rodgers & Hart with the John Wilson Orchestra. Mansfield Park, in September, is a welcome addition to the year, and the first world premiere of specially-commissioned work to take place at The Grange. This newly-orchestrated version of Mansfield Park was commissioned from Jonathan Dove by The Grange Festival to celebrate the serendipity of two significant milestones for Hampshire occurring in 2017: the 200th anniversary of the death of Austen, and the inaugural season of The Grange Festival in the heart of the county with what promises to be a highly entertaining musical staging of one of her best-loved novels. Mansfield Park was originally written by Jonathan Dove to a libretto by Alasdair Middleton based on the novel by Jane Austen for a cast of ten singers with four hands at a single piano. -

Mark Padmore

` BRITTEN Death in Venice, Royal Opera House, Covent Garden At the centre, there’s a tour de force performance by tenor Mark Padmore as the blocked writer Aschenbach, his voice apparently as fresh at the end of this long evening as at the beginning Erica Jeal, The Guardian, November 2019 Tenor Mark Padmore, exquisite of voice, presents Aschenbach’s physical and spiritual breakdown with extraordinary detail and insight Warwick Thompson, Metro, November 2019 Mark Padmore deals in a masterly fashion with the English words, so poetically charged by librettist Myfanwy Piper, and was in his best voice, teasing out beauty with every lyrical solo. Richard Fairman, The Financial Times, November 2019 Mark Padmore is on similarly excellent form as Aschenbach. Padmore doesn’t do much opera, but this role is perfect for him………Padmore is able to bring acute emotion to these scenes, without extravagance or lyricism, drawing the scale of the drama back down to the personal level. Mark Padmore Gavin Dixon, The Arts Desk, November 2019 Tenor ..It’s the performances of Mark Padmore and Gerald Finley that make the show unmissable. …Padmore……conveys so believably the tragic arc of Aschenbach’s disintegration, from pompous self-regard through confusion and brief ecstatic abandon to physical and moral collapse. And the diction of both singers is so clear that surtitles are superfluous. You will not encounter a finer performance of this autumnal masterpiece. Richard Morrison, The Times, November 2019 BACH St John Passion¸ Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, Simon Rattle. Royal Festival Hall, London Mark Padmore has given us many excellent evangelists, yet this heartfelt, aggrieved, intimate take on St John’s gospel narrative, sometimes spiked with penetrating pauses, still seemed exceptional. -

To Download the Full Archive

Complete Concerts and Recording Sessions Brighton Festival Chorus 27 Apr 1968 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Belshazzar's Feast Walton William Walton Royal Philharmonic Orchestra Baritone Thomas Hemsley 11 May 1968 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Kyrie in D minor, K 341 Mozart Colin Davis BBC Symphony Orchestra 27 Oct 1968 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Philharmonic Society Budavari Te Deum Kodály Laszlo Heltay Brighton Philharmonic Orchestra Soprano Doreen Price Mezzo-Soprano Sarah Walker Tenor Paul Taylor Bass Brian Kay 23 Feb 1969 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Philharmonic Society Symphony No. 9 in D minor, op.125 Beethoven Herbert Menges Brighton Philharmonic Orchestra Soprano Elizabeth Harwood Mezzo-Soprano Barbara Robotham Tenor Kenneth MacDonald Bass Raimund Herincx 09 May 1969 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Mass in D Dvorák Václav Smetáček Czech Philharmonic Orchestra Soprano Doreen Price Mezzo-Soprano Valerie Baulard Tenor Paul Taylor Bass Michael Rippon Sussex University Choir 11 May 1969 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Liebeslieder-Walzer Brahms Laszlo Heltay Piano Courtney Kenny Piano Roy Langridge 25 Jan 1970 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Philharmonic Society Requiem Fauré Laszlo Heltay Brighton Philharmonic Orchestra Soprano Maureen Keetch Baritone Robert Bateman Organ Roy Langridge 09 May 1970 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Mass in B Minor Bach Karl Richter English Chamber Orchestra Soprano Ann Pashley Mezzo-Soprano Meriel Dickinson Tenor Paul Taylor Bass Stafford Dean Bass Michael Rippon Sussex University Choir 1 Brighton Festival Chorus 17 May 1970 Concert Dome Concert Hall, Brighton Brighton Festival Fantasia for Piano, Chorus and Orchestra in C minor Beethoven Symphony No. -

The Ultimate On-Demand Music Library

2020 CATALOGUE Classical music Opera The ultimate Dance Jazz on-demand music library The ultimate on-demand music video library for classical music, jazz and dance As of 2020, Mezzo and medici.tv are part of Les Echos - Le Parisien media group and join their forces to bring the best of classical music, jazz and dance to a growing audience. Thanks to their complementary catalogues, Mezzo and medici.tv offer today an on-demand catalogue of 1000 titles, about 1500 hours of programmes, constantly renewed thanks to an ambitious content acquisition strategy, with more than 300 performances filmed each year, including live events. A catalogue with no equal, featuring carefully curated programmes, and a wide selection of musical styles and artists: • The hits everyone wants to watch but also hidden gems... • New prodigies, the stars of today, the legends of the past... • Recitals, opera, symphonic or sacred music... • Baroque to today’s classics, jazz, world music, classical or contemporary dance... • The greatest concert halls, opera houses, festivals in the world... Mezzo and medici.tv have them all, for you to discover and explore! A unique offering, a must for the most demanding music lovers, and a perfect introduction for the newcomers. Mezzo and medici.tv can deliver a large selection of programmes to set up the perfect video library for classical music, jazz and dance, with accurate metadata and appealing images - then refresh each month with new titles. 300 filmed performances each year 1000 titles available about 1500 hours already available in 190 countries 2 Table of contents Highlights P. -

The-Corridor-The-Cure-Programma

thE Corridor & thE curE HARRISON BIRTWISTLE DAVID HARSENT LONDON SINFONIETTA INHOUD CONTENT INFO 02 CREDITS 03 HARRISON BIRTWISTLE, MEDEA EN IK 05 HARRISON BIRTWISTLE, MEDEA AND ME 10 OVER DE ARTIESTEN 14 ABOUT THE ARTISTS 18 BIOGRAFIEËN 16 BIOGRAPHIES 20 HOLLAND FESTIVAL 2016 24 WORD VRIEND BECOME A FRIEND 26 COLOFON COLOPHON 28 1 INFO DO 9.6, VR 10.6 THU 9.6, FRI 10.6 aanvang starting time 20:30 8.30 pm locatie venue Muziekgebouw aan ’t IJ duur running time 2 uur 5 minuten, inclusief een pauze 2 hours 5 minutes, including one interval taal language Engels met Nederlandse boventiteling English with Dutch surtitles inleiding introduction door by Ruth Mackenzie (9.6), Michel Khalifa (10.6) 19:45 7.45 pm context za 11.6, 14:00 Sat 11.6, 2 pm Stadsschouwburg Amsterdam Workshop Spielbar: speel eigentijdse muziek play contemporary music 2 Tim Gill, cello CREDITS Helen Tunstall, harp muziek music orkestleider orchestra manager Harrison Birtwistle Hal Hutchison tekst text productieleiding production manager David Harsent David Pritchard regie direction supervisie kostuums costume supervisor Martin Duncan Ilaria Martello toneelbeeld, kostuums set, costume supervisie garderobe wardrobe supervisor Alison Chitty Gemma Reeve licht light supervisie pruiken & make-up Paul Pyant wigs & make-up supervisor Elizabeth Arklie choreografie choreography Michael Popper voorstellingsleiding company stage manager regie-assistent assistant director Laura Thatcher Marc Callahan assistent voorstellingsleiding sopraan soprano deputy stage manager Elizabeth Atherton -

Adventures Adventures

THEADVENTURESADVENTURES COUNTCOUNT ORYORY Music by Gioachino Rossini CAST: PRODUCTION: Count Ory: Nicholas Sharratt Musical Director: Nicholas Jenkins Raimbaud, a friend of Ory: Benedict Nelson Director: Harry Fehr Ory’s Tutor: Steven Page Designer: Max Dorey Isolier, Ory’s brother: Kate Howden Lighting Designer: Christopher Nairne Two cavaliers, friends of Ory: Benjamin Ellis* Assistant Director: Jack Furness and Guy Elliott* Assistant Musical Director: Jeremy Cooke Countess Adele: Anna Devin Production Manager: Rene (Freddy) Marchal Ragonde , a friend of the Countess: Louise Winter Costume Supervisor: Felicity Langthorne A lady, another friend of the Countess: Costume Assistant: Jo Ray Claire Barton* Hair and Make-Up: Maisie Palmer Alice, a villager: Zoe Freedman* Production Assistant: Sophie Horan *Vocal student at Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music and Dance Senior Stage Manager: Sasja Ekenberg Deputy Stage Manager: Marian Sharkey Blackheath Halls Opera Chorus Assistant Stage Managers: Mimi Palmer-Johnston Blackheath Halls Orchestra and Rosanna Grimes Pupils from Greenvale School Community Stage Manager: Sarah Southerton Pupils from Charlton Park Academy Technical Assistant Stage Manager: Pupils from Year 5 at St Margaret’s Primary School Oliver Ballantyne Pupils from Year 4 at Lee Manor Primary School Project Manager: Rose Ballantyne Assistant Project Manager: Alice Murray BLACKHEATH HALLS TEAM: General Manager: Keith Murray Publicity and Programme Designer: Community Engagement Manager: Rose Ballantyne Colin Dunlop Operations Manager: Hannah Benton TRINITY LABAN PROJECT TEAM: Technical Manager: Malcolm Richards Programme Manager: Anna Wyatt and Marketing and Box Office Co-ordinator:Kyle Jarvis Helen Hendry Development Officer:Helma Zebregs Project Leader: Joe Townsend Bookkeeper: Debra Skeet Administrator: Caroline Foulkes Running time: 2hrs and 30mins We have been staging community operas at Blackheath WELCOME Halls since July 2007. -

For Harp and Woodwind Quartet

Mike Magatagan Arranger, Composer, Interpreter, Publisher United States (USA), SierraVista About the artist I'm a software engineer. Basically, I'm computer geek who loves to solve problems. I have been developing software for the last 25+ years but have recently rekindled my love of music. Many of my scores are posted with individual parts and matching play-along however, this is not always practical. If you would like individual parts to any of my scores or other specific tailoring, please contact me directly and I will try to accommodate your specific needs. Artist page : https://www.free-scores.com/Download-PDF-Sheet-Music-magataganm.htm About the piece Title: "For unto us, a Child is Born" for Harp and Woodwind Quartet [HWV 56] Composer: Haendel, Georg Friedrich Arranger: Magatagan, Mike Copyright: Public Domain Publisher: Magatagan, Mike Instrumentation: Woodwinds & Harp Style: Baroque Comment: The Messiah (HWV 56) is an English-language oratorio composed in 1741 by George Frideric Handel, with a scriptural text compiled by Charles Jennens from the King James Bible, and from the Psalms included with the Book of Common Prayer (which are worded slightly differently from their King James counterparts). It was first performed in Dublin on 13 April 1742, and received its London premiere nearly a year later. After an initially modest public... (more online) Mike Magatagan on free-scores.com • listen to the audio • share your interpretation • comment • contact the artist First added the : 2013-01-02 Last update : 2013-01-01 21:46:29 "For unto us, a Child is Born" (Chorus from "Messiah" Part III) G.F. -

Newsletter Wednesday 28Th July 2021

Winchester City Festival Choir NEWSLETTER WEDNESDAY 28TH JULY 2021 Welcome to another edition of ramblings from the conductor! I hope the newsletter continues to find you well. We continue our reminiscing through the archive; and find ourselves at the year 2016. From the Archives: 2016 At the beginning of 2015, Winchester City Festival Choir had their annual concert in January (or it might have been the beginning of February). For the first time, it was held at Thornden Hall in Chandler’s Ford, which, when open, is an excellent venue for choral concerts! The programme for this concert was, I guess, what you would call a “crowd pleasing” one: Haydn's Nelson Mass and Vivaldi's Gloria. If you click on the Vivaldi link in blue, you’ll be able to a unique version of the work, performed by an all-female orchestra and choir in the Pieta in Venice. In the original conversations about this programme, I hoped that we would be able to feature a Trombone Concerto from roughly the same period, by a composer called Johann Georg Albrechtsberger (1736 – 1809). Albrechtsberger was an Austrian composer, organist, and music theorist, and one of the teachers of Beethoven. He was an acquaintance of Mozart and Haydn; indeed, he passed away the same year as Haydn. Going off a tangent slightly, 1809 was a very significant year for composers, with the death of Haydn and birth of Mendelssohn. The plan was to have the Principal Trombonist of the BBC Symphony Orchestra Helen Vollam (pictured above left) to be our esteemed soloist (Helen was one of my patient trombone teachers at University), but sadly we didn’t pull it off… but we were able to showcase two excellent members of the orchestra for this concert, who played a short concerto each. -

THE CREATION Joseph Haydn

Cantorum Choir and Orchestra Music Director - Oliver Gooch THE CREATION Joseph Haydn Saturday 19th October, 7.30pm ALL SAINTS CHURCH, MARLOW Registered Charity no:1136210 Creation Programme.indd 1 15/10/2019 10:30 Patron: Ralph Allwood MBE Music Director: Oliver Gooch Associate Music Director: Robert Jones Cantorum Choir is a dedicated and talented choir of approximately forty voices, based in Cookham, Berkshire. The ensemble boasts a wide-ranging repertoire and performs professional-quality concerts throughout the year. Under the directorship of Oliver Gooch, it has continued to earn itself a reputation as one of the leading chamber choirs in the area. SOPRANOS ALTOS TENORS BASSES Clare Dolan Angela Plant John Timewell Ben Styles Daphne Rowbottom Anne Glover Jonny Manktelow David Hazeldine Deborah Templing Chiu Sung Malcolm Stork Ed Millard Jenny Knight Elspeth Scott Peter Roe Gordon Donkin Joy Strzelecki Gill Tucker Philip Martineau James Simpson Kate Cromar Jill Burton Richard Palfrey John Buck Kirsty Janusz Lorna Sykes Paul Reid Louise Evans Sarah Evans Paul Seddon Pippa Wallace Sandy Johnstone Eve – Kirsty Janusz, Adam – Ed Millard, Alto solo – Jill Burton and Sarah Evans ORCHESTRA Leader Caroline Balding Flute 1 Hannah Grayson Horn 1 Jon Hassan Violin 2 Simon Kodurand Flute 2 Renate Sokolovska Horn 2 Jane Hanna Viola Vanessa McNaught Oboe Katie Bennington Trumpet Alex Caldon Cello Joseph Spooner Clarinet Karen Hobbs Trombone Jim Alexander Bass Sean Law Bassoon Jo Turner Timpani Daniel Floyd Creation Programme.indd 2 15/10/2019 10:30 -

Scottish Opera Announces 2018/19 Season

PRESS RELEASE 11 April 2018 ** EMBARGOED UNTIL 00:00:01, 11 April 2018** SCOTTISH OPERA ANNOUNCES 2018/19 SEASON • World premiere of Stuart MacRae and Louise Welsh’s Anthropocene performed in Glasgow, Edinburgh and London • New staging of Janáček’s Kátya Kabanová directed by Stephen Lawless • Matthew Richardson directs revival production of Verdi’s Rigoletto to open the Season • Sir Thomas Allen’s acclaimed staging of Mozart’s The Magic Flute closes the Season • Promenade production of Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci at ‘Paisley Opera House’ • Scottish premieres of rarely-performed gems by Puccini and Mascagni in the Opera in Concert series curated by Music Director Stuart Stratford • Britten’s The Burning Fiery Furnace at Lammermuir Festival • BambinO returns to Edinburgh Festival Fringe and tours Scotland following dates in Paris and New York • New production of Orfeo & Euridice by Scottish Opera Young Company • Special performances of Pop-up Opera during Glasgow 2018 European Championships, as part of Festival 2018 Scottish Opera has unveiled its 2018/19 Season which includes a world premiere, two new productions (one a co-production with Germany’s Theater Magdeburg), two revivals, a new 1 production of Orfeo & Euridice by Scottish Opera Young Company, two Scottish premieres in the Opera in Concert series and appearances at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe and Lammermuir Festival, as well as in Paris, London and New York. A truly international line-up of singers appears throughout the Season. Making their debuts with the Company are Aris Argiris, Lina Johnson, Adam Smith, David Shipley, Laura Wilde, Ric Furman, Gemma Summerfield, Julia Sitkovetsky, Ronald Samm, Anna Patalong and Emma Bell. -

Patrick Allen Program

EVENSONG AT GRACE CHURCH IN NEW YORK EPISCOPAL SPECIAL CHORAL MUSICAL OFFERINGS BY THE GRACE CHURCH CHOIRS FREE ADMISSION TENTH STREET AT BROADWAY TELEPHONE 212-254-200 0/6 WWW.GRACECHURCHNYC.ORG Photo: Chorister Window in the Honor Room by Vincent Dixon Design: ARTeffect 2015-2016 SEASON Sunday Afternoons at 4:00 p.m. unless otherwise noted 18 October REJOICE IN THE LAMB BY BENJAMIN BRITTEN The Choir of Men and Boys 1 November REQUIEM BY GABRIEL FAURÉ The Adult Choir with The Parish Choir Sunday 11:00 a.m. in the Church, 22 November GRACE CHURCH SCHOOL SUNDAY Welcome Home Alumni of the Choirs! 6 December ADVENT LESSONS AND MUSIC The Adult Choir Wednesday 12:15 – 12:45 p.m. in the Church, 9 December THE COMMUNITY CAROL SING The Combined Boys’ and Girls’ Choirs 13 December A CEREMONY OF CAROLS BY BENJAMIN BRITTEN The Girls’ Choir with Alumni of the Choir and members of the Adult and Parish Choirs Thursday 8:00 p.m. in the Church, 24 December A FESTIVAL OF NINE LESSONS AND CAROLS The Choir of Men and Boys with The Girls’ Choir 3 January AMAHL AND THE NIGHT VISITORS BY GIAN CARLO MENOTTI The Adult Choir 24 January THE EIGHTH ANNUAL CONCERT OF MUSIC FOR TREBLE VOICES The Junior Choristers of the Grace Church Choirs with Dr. Barry Rose 20 March EXCERPTS FROM HANDEL’S MESSIAH PART II The Adult Choir Good Friday 7:00 p.m. in the Church, 25 March CRUCIFIXION BY JOHN STAINER The Adult Choir 10 April EXCERPTS FROM HANDEL’S MESSIAH PART III The Adult Choir with the Parish Choir Friday 7:00 p.m. -

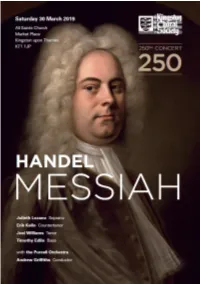

2.0 2019-03-30-Messiah-Website.Pub

Since its formation in 1949, Kingston Choral Society has earned a reputation for concerts of a high standard and for performing a wide range of music. The Society enjoys singing the familiar favourites of the choral repertoire, but is not afraid of tackling ambitious projects and has, for example, performed a new commission by Peter Maxwell Davies, Prokofiev’s Alexander Nevsky in Russian and other pieces in Czech, Hebrew, Finnish and Swedish. Kingston Choral Society has over 130 members drawn from southwest London and north Surrey. New members are welcome. The choir performs four concerts a year, usually in All Saints Church, Kingston, and St Andrew’s Church, Surbiton. Two of the concerts are with a professional orchestra. Rehearsals are held on Thursday evenings (8-10 pm) at The Hollyfield School, Surbiton, in term-time. Kingston Choral Society also holds regular social and fundraising events and occasional musical workshops. If you are interested in joining, please talk to any member of the choir during the interval or at the end of the concert. You can also contact the Membership Secretary on 020 8949 5253 or [email protected] for more information and arrange to come to a rehearsal. ~ ~ NEXT KCS CONCERT ~ ~ 29th June 2019 at 7.30 pm Duruflé Requiem - Bruch Die Macht des Gesanges - Tavener Svyati - Vierne Les Angélus Mezzosoprano: Penelope Cousland; Baritone: Gareth Brynmor John; Organ: James Orford; Cello: Clare O’Connell Andrew Griffiths - Conductor St Andrew’s Church, Maple Road, Surbiton KT6 4DS For further details